Protecting Chek Jawa: the Politics of Conservation and Memory at the Edge of a Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Registration Is Now Open for the AWA Valentine's Event Celebrate Chinese

BAMBOO TELEGRAPH FOR ALL WOMEN, ALL WALKS OF LIFE, ALL NATIONALITIES JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 Registration is now open for the AWA valentine’s event SIGN UP FOR OUR NEXT EXCITING FOREIGN TOUR TO BEAUTIFUL BALI celebrate chinese new NEW YEAR’S TIPS year with AN awa lunch TO CLEAN UP YOUR or dinner CLOSET, COMPUTER AND KIDS CLUTTER Showroom/Warehouse, No.1, Syed Alwi Road, #03-02, Song Lin Building, 207628 BTJAN/FEB 2019 Bamboo Telegraph Production Team Contents BT Editors Tori Nelson Niki Cholet 2 President’s Message 6 [email protected] 3 Board Nominations 4 BT Staff Arts & Culture Helena A. Cochrane 5 Valentine’s Event Lorraine Graybill 6 Community Service Kanika Karu Prachi Rangan 8 Member Spotlight Celine Suiter 10 Tech Talk 12 11 Beauty & Fashion BT Advertising Robin Phillips 12 Foreign Tours [email protected] 13 AWA Workshops 14 Ready in 5 Visit us on the internet: 15 www.awasingapore.org Model Call & Fashion Show 16 Photography 16 Facebook: 18 Local Tours American Women’s Association of 21 The Fork and Chopstick Singapore - AWA 22 Home Tour Questions, comments andadministrative 25 You’re Not Alone issues, please email us: 26 Carpet Auction [email protected] 27 International Choir 22 Printed by 28 Tennis Xpress Print (Pte) Ltd 29 Running 6880-2881, fax 6880-2998 [email protected] 30 Golf MCI (P) 099/06/2018 31 Writers’ Block 32 Calendar 29 AWA Registration Policies • Bookings open on the first working day of the month. • You must register in advance to attend an event, online registration is available at www.awasingapore.org • If an event is full, please join the waitlist. -

RSG Book PDF Version.Pub

GLOBAL RE-INTRODUCTION PERSPECTIVES Re-introduction case-studies from around the globe Edited by Pritpal S. Soorae The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or any of the funding organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Environment Agency - Abu Dhabi or Denver Zoological Foundation. Published by: IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group Copyright: © 2008 IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Soorae, P. S. (ed.) (2008) GLOBAL RE-INTRODUCTION PERSPECTIVES: re-introduction case-studies from around the globe. IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group, Abu Dhabi, UAE. viii + 284 pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1113-3 Cover photo: Clockwise starting from top-left: • Formosan salmon stream, Taiwan • Students in Madagascar with tree seedlings • Virgin Islands boa Produced by: IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group Printed by: Abu Dhabi Printing & Publishing Co., Abu Dhabi, UAE Downloadable from: http://www.iucnsscrsg.org (downloads section) Contact Details: Pritpal S. Soorae, Editor & RSG Program Officer E-mail: [email protected] Plants Conservation and re-introduction of the tiger orchid and other native orchids of Singapore Tim Wing Yam Senior Researcher, National Parks Board, Singapore Botanic Gardens, 1 Cluny Road, Singapore 259569 ([email protected]) Introduction Singapore consists of a main island and many offshore islands making up a total land area of more than 680 km2. -

From Tales to Legends: Discover Singapore Stories a Floral Tribute to Singapore's Stories

Appendix II From Tales to Legends: Discover Singapore Stories A floral tribute to Singapore's stories Amidst a sea of orchids, the mythical Merlion battles a 10-metre-high “wave” and saves a fishing village from nature’s wrath. Against the backdrop of an undulating green wall, a sorcerer’s evil plan and the mystery of Bukit Timah Hill unfolds. Hidden in a secret garden is the legend of Radin Mas and the enchanting story of a filial princess. In celebration of Singapore’s golden jubilee, 10 local folklore are brought to life through the creative use of orchids and other flowers in “Singapore Stories” – a SG50-commemorative floral display in the Flower Dome at Gardens by the Bay. Designed by award-winning Singaporean landscape architect, Damian Tang, and featuring more than 8,000 orchid plants and flowers, the colourful floral showcase recollects the many tales and legends that surround this city-island. Come discover the stories behind Tanjong Pagar, Redhill, Sisters’ Island, Pulau Ubin, Kusu Island, Sang Nila Utama and the Singapore Stone – as told through the language of plants. Along the way, take a walk down memory lane with scenes from the past that pay tribute to the unsung heroes who helped to build this nation. Date: Friday, 31 July 2015 to Sunday, 13 September 2015 Time: 9am – 9pm* Location: Flower Dome Details: Admission charge to the Flower Dome applies * Extended until 10pm on National Day (9 August) About Damian Tang Damian Tang is a multiple award-winning landscape architect with local and international titles to his name. -

Singapore | October 17-19, 2019

BIOPHILIC CITIES SUMMIT Singapore | October 17-19, 2019 Page 3 | Agenda Page 5 | Site Visits Page 7 | Speakers Meet the hosts Biophilic Cities partners with cities, scholars and advocates from across the globe to build an understanding of the importance of daily contact with nature as an element of a meaningful urban life, as well as the ethical responsibility that cities have to conserve global nature as shared habitat for non- human life and people. Dr. Tim Beatley is the Founder and Executive Director of Biophilic Cities and the Teresa Heinz Professor of Sustainable Communities, in the Department of Urban and Environmental Planning, School of Architecture at the University of Virginia. His work focuses on the creative strategies by which cities and towns can bring nature into the daily lives of thier residents, while at the same time fundamentally reduce their ecological footprints and becoming more livable and equitable places. Among the more than variety of books on these subjects, Tim is the author of Biophilic Cities and the Handbook of Bophilic City Planning & Design. The National Parks Board (NParks) of Singapore is committed to enhancing and managing the urban ecosystems of Singapore’s biophilic City in a Garden. NParks is the lead agency for greenery, biodiversity conservation, and wildlife and animal health, welfare and management. The board also actively engages the community to enhance the quality of Singapore’s living environment. Lena Chan is the Director of the National Biodiversity Centre (NBC), NParks, where she leads a team of 30 officers who are responsible for a diverse range of expertise relevant to biodiversity conservation. -

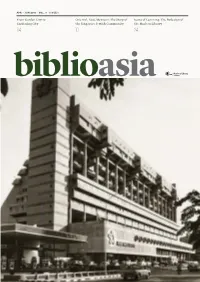

Apr–Jun 2013

VOL. 9 iSSUe 1 FEATURE APr – jUn 2013 · vOL. 9 · iSSUe 1 From Garden City to Oriental, Utai, Mexican: The Story of Icons of Learning: The Redesign of Gardening City the Singapore Jewish Community the Modern Library 04 10 24 01 BIBLIOASIA APR –JUN 2013 Director’s Column Editorial & Production “A Room of One’s Own”, Virginia Woolf’s 1929 essay, argues for the place of women in Managing Editor: Stephanie Pee Editorial Support: Sharon Koh, the literary tradition. The title also makes for an apt underlying theme of this issue Masamah Ahmad, Francis Dorai of BiblioAsia, which explores finding one’s place and space in Singapore. Contributors: Benjamin Towell, With 5.3 million people living in an area of 710 square kilometres, intriguing Bernice Ang, Dan Koh, Joanna Tan, solutions in response to finding space can emerge from sheer necessity. This Juffri Supa’at, Justin Zhuang, Liyana Taha, issue, we celebrate the built environment: the skyscrapers, mosques, synagogues, Noorashikin binte Zulkifli, and of course, libraries, from which stories of dialogue, strife, ambition and Siti Hazariah Abu Bakar, Ten Leu-Jiun Design & Print: Relay Room, Times Printers tradition come through even as each community attempts to find a space of its own and leave a distinct mark on where it has been and hopes to thrive. Please direct all correspondence to: A sense of sanctuary comes to mind in the hubbub of an increasingly densely National Library Board populated city. In Justin Zhuang’s article, “From Garden City to Gardening City”, he 100 Victoria Street #14-01 explores the preservation and the development of the green lungs of Sungei Buloh, National Library Building Singapore 188064 Chek Jawa and, recently, the Rail Corridor, as breathing spaces of the city. -

How to Prepare the Final Version of Your Manuscript for the Proceedings of the 11Th ICRS, July 2007, Ft

Proceedings of the 12th International Coral Reef Symposium, Cairns, Australia, 9-13 July 2012 22A Social, economic and cultural perspectives Conservation of our natural heritage: The Singapore experience Jeffrey Low, Liang Jim Lim National Biodiversity Centre, National Parks Board, 1 Cluny Road, Singapore 259569 Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract. Singapore is a highly urbanised city-state of approximately 710 km2 with a population of almost 5 million. While large, contiguous natural habitats are uncommon in Singapore, there remains a large pool of biodiversity to be found in its four Nature Reserves, 20 Nature Areas, its numerous parks, and other pockets of naturally vegetated areas. Traditionally, conservation in Singapore focused on terrestrial flora and fauna; recent emphasis has shifted to marine environments, showcased by the reversal of development works on a unique intertidal shore called Chek Jawa (Dec 2001), the legal protection of Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve (mangrove and mudflat habitats) and Labrador Nature Reserve (coastal habitat) in 2002, the adoption of a national biodiversity strategy (September 2009) and an integrated coastal management framework (November 2009). Singapore has also adopted the “City in a Garden” concept, a 10-year plan that aims to not only heighten the natural infrastructure of the city, but also to further engage and involve members of the public. The increasing trend of volunteerism, from various sectors of society, has made “citizen-science” an important component in many biodiversity conservation projects, particularly in the marine biodiversity-rich areas. Some of the key outputs from these so-called “3P” (people, public and private) initiatives include confirmation of 12 species of seagrasses in Singapore (out of the Indo-Pacific total of 23), observations of new records of coral reef fish species, long term trends on the state of coral reefs in one of the world's busiest ports, and the initiation of a Comprehensive Marine Biodiversity Survey project. -

From Orphanage to Entertainment Venue: Colonial and Post-Colonial Singapore Reflected in the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus

From Orphanage to Entertainment Venue: Colonial and post-colonial Singapore reflected in the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus by Sandra Hudd, B.A., B. Soc. Admin. School of Humanities Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, September 2015 ii Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the Universityor any other institution, except by way of backgroundi nformationand duly acknowledged in the thesis, andto the best ofmy knowledgea nd beliefno material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text oft he thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. �s &>-pt· � r � 111 Authority of Access This thesis is not to be made available for loan or copying fortwo years followingthe date this statement was signed. Following that time the thesis may be made available forloan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. :3 £.12_pt- l� �-- IV Abstract By tracing the transformation of the site of the former Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus, this thesis connects key issues and developments in the history of colonial and postcolonial Singapore. The convent, established in 1854 in central Singapore, is now the ‗premier lifestyle destination‘, CHIJMES. I show that the Sisters were early providers of social services and girls‘ education, with an orphanage, women‘s refuge and schools for girls. They survived the turbulent years of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore and adapted to the priorities of the new government after independence, expanding to become the largest cloistered convent in Southeast Asia. -

Lion City Adventures Secrets of the Heartlandsfor Review Only Join the Lion City Adventuring Club and Take a Journey Back in Time to C

don bos Lion City Adventures secrets of the heartlandsFor Review only Join the Lion City Adventuring Club and take a journey back in time to C see how the fascinating heartlands of Singapore have evolved. o s ecrets of the Each chapter contains a history of the neighbourhood, information about remarkable people and events, colourful illustrations, and a fun activity. You’ll also get to tackle story puzzles and help solve an exciting mystery along the way. s heA ArtL NDS e This is a sequel to the popular children’s book, Lion City Adventures. C rets of the he rets the 8 neighbourhoods feAtured Toa Payoh Yishun Queenstown Tiong Bahru Kampong Bahru Jalan Kayu Marine Parade Punggol A rt LA nds Marshall Cavendish Marshall Cavendish In association with Super Cool Books children’s/singapore ISBN 978-981-4721-16-5 ,!7IJ8B4-hcbbgf! Editions i LLustrAted don bos Co by shAron Lei For Review only lIon City a dventures don bosco Illustrated by VIshnu n rajan L I O N C I T Y ADVENTURING CLUB now clap your hands and repeat this loudly: n For Review only orth, south, east and west! I am happy to do my best! Editor: Melvin Neo Designer: Adithi Shankar Khandadi Illustrator: Vishnu N Rajan © 2015 Don Bosco (Super Cool Books) and Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Pte Ltd y ou, This book is published by Marshall Cavendish Editions in association with Super Cool Books. Reprinted 2016, 2019 ______________________________ , Published by Marshall Cavendish Editions (write your name here) An imprint of Marshall Cavendish International are hereby invited to join the All rights reserved lion city adventuring club No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval systemor transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, on a delightful adventure without the prior permission of the copyright owner. -

ST/LIFE/PAGE<LIF-008>

C8 life happenings | THE STRAITS TIMES | FRIDAY, MARCH 13, 2020 | FILMS John Lui Film Correspondent recommends Roll With The Trolls Movie Event Trolls World Tour (2020, PG) is the sequel to the 2016 animated film Picks Trolls. It tells the story of Poppy and Branch, who discover they are from one of six Troll tribes, each dedicated Film to a different genre of music. They set out to unite the tribes as Queen Barb, a member of hard-rock royalty, plans to destroy all other kinds of music. The ticket price includes an activity pack, sand-art activity and chocolate popcorn with marshmallow. WHERE: Cathay Cineplex Parkway Parade, Level 7 Parkway Parade, 80 Marine Parade Road MRT: Eunos WHEN: Tomorrow, 10.30am - 3pm ADMISSION: $15 (single ticket), $58 (family bundle of four tickets) INFO: www.cathaycineplexes.com.sg In The Name Of The Land (PG13) Pierre is 25 when he returns from Wyoming to find Claire, his fiancee, has taken over the family farm. Two decades later, despite the expansion of his farm and family, the accumulated debts and work take a toll on Pierre. The screening will be followed by a live Skype question- and-answer session with French director Edouard Bergeon (nominated for Cesar Awards: Best First Feature Film and Audience Award) and writer Emmanuel Courcol (Ceasefire, 2016; Face Down, 2015). Part of the Francophonie Festival. WHERE: Alliance Francaise, 1 Sarkies Road MRT: Newton WHEN: Wed, 8pm ADMISSION: $15 INFO: alliancefrancaise.org.sg The Lighthouse (M18) From Robert Eggers, the film-maker behind modern horror masterpiece PRINCESS MONONOKE (PG) work, Spirited Away (2001). -

The Singapore Urban Systems Studies Booklet Seriesdraws On

Biodiversity: Nature Conservation in the Greening of Singapore - In a small city-state where land is considered a scarce resource, the tension between urban development and biodiversity conservation, which often involves protecting areas of forest from being cleared for development, has always been present. In the years immediately after independence, the Singapore government was more focused on bread-and-butter issues. Biodiversity conservation was generally not high on its list of priorities. More recently, however, the issue of biodiversity conservation has become more prominent in Singapore, both for the government and its citizens. This has predominantly been influenced by regional and international events and trends which have increasingly emphasised the need for countries to show that they are being responsible global citizens in the area of environmental protection. This study documents the evolution of Singapore’s biodiversity conservation efforts and the on-going paradigm shifts in biodiversity conservation as Singapore moves from a Garden City to a City in a Garden. The Singapore Urban Systems Studies Booklet Series draws on original Urban Systems Studies research by the Centre for Liveable Cities, Singapore (CLC) into Singapore’s development over the last half-century. The series is organised around domains such as water, transport, housing, planning, industry and the environment. Developed in close collaboration with relevant government agencies and drawing on exclusive interviews with pioneer leaders, these practitioner-centric booklets present a succinct overview and key principles of Singapore’s development model. Important events, policies, institutions, and laws are also summarised in concise annexes. The booklets are used as course material in CLC’s Leaders in Urban Governance Programme. -

Circle Line Guide

SMRT System Map STOP 4: Pasir Panjang MRT Station Before you know, it’s dinner LEGEND STOP 2: time! Enjoy a sumptuous East West Line EW Interchange Station Holland Village MRT Station meal at the Pasir Panjang North South Line NS Bus Interchange near Station Food Centre, which is just Head two stops down to a stop away and is popular Circle Line CC North South Line Extension Holland Village for lunch. (Under construction) for its BBQ seafood and SMRT Circle Line Bukit Panjang LRT BP With a huge variety of cuisines Malay fare. Stations will open on 14 January 2012 available, you’ll be spoilt for STOP 3: choice of food. Haw Par Villa MRT Station STOP 1: Spend the afternoon at the Haw Botanic Gardens MRT Station Par Villa and immerse in the rich Start the day with some fresh air and Chinese legends and folklore, nice greenery at Singapore Botanic dramatised through more than Gardens. Enjoy nature at its best or 1,000 statues and dioramas have fun with the kids at the Jacob found only in Singapore! Ballas Garden. FAMILY. TIME. OUT. Your Handy Guide to Great Food. Fun Activities. Fascinating Places. One day out on the Circle Line! For Enquiries/Feedback EAT. SHOP. CHILL. SMRT Customer Relations Centre STOP 1: Buona Vista Interchange Station 1800 336 8900 A short walk away and you’ll find 7.30am to 6.30pm STOP 3: yourself at Rochester Park where Mondays – Fridays, except Public Holidays you can choose between a hearty Haw Par Villa MRT Station SMRT Circle Line Quick Facts Or send us an online feedback at American brunch at Graze or dim Venture back west for dinner www.smrt.com.sg/contact_us.asp Total route length: 35.4km Each train has three cars, 148 seats and can take up to 670 sum at the Min Jiang at One-North after a day at the mall. -

Past, Present and Future: Conserving the Nation’S Built Heritage 410062 789811 9

Past, Present and Future: Conserving the Nation’s Built Heritage Today, Singapore stands out for its unique urban landscape: historic districts, buildings and refurbished shophouses blend seamlessly with modern buildings and majestic skyscrapers. STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS This startling transformation was no accident, but the combined efforts of many dedicated individuals from the public and private sectors in the conservation-restoration of our built heritage. Past, Present and Future: Conserving the Nation’s Built Heritage brings to life Singapore’s urban governance and planning story. In this Urban Systems Study, readers will learn how conservation of Singapore’s unique built environment evolved to become an integral part of urban planning. It also examines how the public sector guided conservation efforts, so that building conservation could evolve in step with pragmatism and market considerations Heritage Built the Nation’s Present and Future: Conserving Past, to ensure its sustainability through the years. Past, Present “ Singapore’s distinctive buildings reflect the development of a nation that has come of age. This publication is timely, as we mark and Future: 30 years since we gazetted the first historic districts and buildings. A larger audience needs to learn more of the background story Conserving of how the public and private sectors have creatively worked together to make building conservation viable and how these efforts have ensured that Singapore’s historic districts remain the Nation’s vibrant, relevant and authentic for locals and tourists alike, thus leaving a lasting legacy for future generations.” Built Heritage Mrs Koh-Lim Wen Gin, Former Chief Planner and Deputy CEO of URA.