Re-Thinking Gig Economy in Conventional Workforce Post-COVID

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intersectionality of Technology, People and Planning for Resilience 14Th August 2021 11.00 Am to 01.30 Pm

WEBINAR Intersectionality of Technology, People and Planning for Resilience 14th August 2021 11.00 am to 01.30 pm Programme 11.00 am -11.15 am Welcome and Introduction - Prof Kajri Misra, Dean, Xavier School of Human Settlements, XIM University Bhubaneswar About BREUCom - Dr Barsha Paricha, Technical Specialist, Centre for Urban and Regional Excellence Inaugural Remarks - Prof. Dr. Fr Antony Uvary, S.J., Vice Chancellor, XIM University, Bhubaneswar - 11.15 am - 12.15 pm : Panel Discussion Understanding Intersectionality of Technology, People and Planning for Resilience Chair Prof Kajri Misra (3-4 minutes) The Chair will briefly introduce the relevance of the topic, key points for discussion, and the panellists (just name and designation). Short bios of each panellist will be shared on chat feature of Zoom. Panellists (7 minutes each): Each panellists will initially speak for 5-6 minutes sharing their perspective and experience. • Dr Barsha Paricha, Technical Specialist, Centre for Urban and Regional Excellence [focussing on case studies - 2, 3 & 8] • Dr. Tathagata Chatterjee, School of Human Settlements, XIM University • Dr. Partha Mukhopadhyay, Fellow, CPR Delhi Open Discussion (15 minutes) Participants will be encouraged to write their comments and questions using Q&A feature in Zoom. 3-4 participants can be requested to speak. Chair will request each panellist to respond to various questions and comments in 2 minutes. Consolidation by the Chair (5 minutes) Chair will consolidate the key points discussed in the session as well as add her/his perspectives. 12.15 pm - 12.20 pm Screen Break 12.20 pm – 01.20 pm :Roundtable Conversation Remodelling Urban Planning and Management Education for Future Urban Resilience This session will be conducted in three parts. -

Nipfp-Iipf International Conference on “Papers in Public Finance” June 29-30 2021 New Delhi

NIPFP-IIPF INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON “PAPERS IN PUBLIC FINANCE” JUNE 29-30 2021 NEW DELHI Keynote Address June 29, 2021 (16.00-17.30 IST) “THE IMPACT OF THE CORONA CRISIS ON PUBLIC FINANCES” Clemens Fuest, President Ifo Institute and President, International Institute of Public Finance, Munich Chair : Pinaki Chakraborty, Director, National Institute of Public Finance And Policy, New Delhi NIPFP-IIPF Scientific Committee Chairs Paola Profeta , Professor, BOCCONI UNIVERSITY and Member, IIPF Board of Management Lekha Chakraborty, Professor, NIPFP and Member, IIPF Board of Management. Conference Co-ordinator Amandeep Kaur, Economist, NIPFP DAY 1- June 29, 2021 SESSION I - FISCAL POLICY, DEBT/DEFICITS AND ECONOMIC ACTIVITY Tuesday, June 29 (9.00-10.40 IST) Chair: ILA PATNAIK, Professor, NIPFP and former Principal Economic Advisor, Government of India, New Delhi, INDIA 1. Fiscal Dominance in India: Through the Windshield and 3. Lights out? COVID-19 Containment Policies and the Rearview Mirror (India 09.00) Economic Activity (India 09.00) Author: Anshuman Kamila (Department of Economic Affairs, Author: Robert C M Beyer (Macro, Trade and Investment Ministry of Finance, Government of India, New Delhi, INDIA) Global Practice, World Bank, Washington DC, US), and Discussant: Piyali Das Tarun Jain (Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, INDIA), Sonalika Sinha (Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai, 2. Public Debt in India: A Security Level Analysis (India INDIA) 09.00) Discussant: Binod Kumar Behera Author::Piyali Das (Indian Institute of Management Indore, INDIA) and Chetan Ghate (Economics and Planning Unit, 4. Effect of Fiscal Deficit on Economic Growth Performance Indian Statistical Institute – Delhi, INDIA) of Indian States (India 09.00) Discussant: Tarun Jain Author: Binod Kumar Behera (Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, INDIA) Discussant: Anshuman Kamila SESSION II: INTERNATIONAL TAXATION Tuesday, June 29 (11.30-13.10 IST) Chair: KAVITA RAO, Professor, NIPFP, New Delhi, INDIA 5. -

Batch Profile 2020-22 Master of Business Finance XIM University (Erstwhile XIMB)

Batch Profile 2020-22 Master of Business Finance XIM University (erstwhile XIMB) ABHISHEK DHIR Graduation Degree: B.Com, Utkal University Graduation Percentage: 65.3% Areas of Interest: Financial Statement Analysis, Law,Strategy Formulation Certification: Common Proficiency Test Position Of Responsibility: Junior Member of Alumni Committee, Social Responsibility Cell and PRESM Email:[email protected] Mobile No: +91-9437195100 ARCHIT GANERIWAL Graduation Degree: BBA (Finance and Accountancy), Christ University Graduation Percentage: 72.9% Work Experience: 28 Months, Dindayal Jalan Textiles Areas of Interest: Equity Research, Corporate Finance, Fixed Income, Valuations. Industry Research, Private Equity Internship / Training : TresVista Financial Services, PwC India Certification: ACCA (In-Progress) Position Of Responsibility: Junior member of Corporate Relation Team Email: [email protected] Mobile No.:+91-7355756142 MBF BATCH PROFILE, XIMU AYANTICA DHAR Graduation Degree: BBA, Gayatri Vidya Parishad, Andhra University Graduation Percentage: 8.78 CGPA Areas of Interest: investment banking, financial modelling, cost accounting, financial analysis, valuation, financial management, accounting. Certification: Tally, MS office and MS Excel . Position Of Responsibility: Junior member of InfinX , Sportscomm, X-cubate and PRESM Email: [email protected] Mobile No.: +91-9966710867 HARNEEL DESAI Graduation Degree: BBA (Finance), Amity Global Business School Graduation Percentage:8.83 CGPA Work Experience: 8 months, Appco Group -

Consolidated List Private Universities

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION State-wise List of Private Universities as on 06.08.2021 S.No Name of Private University Date of Notification ARUNACHAL PRADESH 1. Apex Professional University, Pasighat, District East Siang, 10.05.2013 Arunachal Pradesh - 791102. 2. Arunachal University of Studies, NH-52, Namsai, Distt – Namsai 26.05.2012 - 792103, Arunachal Pradesh. 3. Arunodaya University, E-Sector, Nirjuli, Itanagar, Distt. Papum 21.10.2014 Pare, Arunachal Pradesh-791109 4. Himalayan University, 401, Takar Complex, Naharlagun, 03.05.2013 Itanagar, Distt – Papumpare – 791110, Arunachal Pradesh. 5. North East Frontier Technical University, Sibu-Puyi, Aalo 03.09.2014 (PO), West Siang (Distt.), Arunachal Pradesh –791001. 6. The Global University, Hollongi, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. 18.09.2017 7. The Indira Gandhi Technological & Medical Sciences University, 26.05.2012 Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh. 8. Venkateshwara Open University, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. 20.06.2012 Andhra Pradesh 9. Bharatiya Engineering Science and Technology Innovation 17.02.2019 University, Gownivaripalli, Gorantla Mandal, Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh 10. Centurian University of Technology and Management, Gidijala 23.05.2017 Junction, Anandpuram Mandal, Visakhapatnam- 531173, Andhra Pradesh. 11. KREA University, 5655, Central, Expressway, Sri City-517646, 30.04.2018 Andhra Pradesh 12. Saveetha Amaravati University, 3rd Floor, Vaishnavi Complex, 30.04.2018 Opposite Executive Club, Vijayawada- 520008, Andhra Pradesh 13. SRM University, Neerukonda-Kuragallu Village, mangalagiri 23.05.2017 Mandal, Guntur, Dist- 522502, Andhra Pradesh (Private University) 14. VIT-AP University, Amaravati- 522237, Andhra Pradesh (Private 23.05.2017 University) ASSAM 15. Assam Don Bosco University, Azara, Guwahati 12.02.2009 16. Assam Down Town University, Sankar Madhab Path, Gandhi 29.04.2010 Nagar, Panikhaiti, Guwahati – 781 036. -

SACAA Launches ‘ST ALOYSIUS COVID CARE CENTRE’

Editors ST ALOYSIUS COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS), MANGALURU Mr Sonal Steevan Lobo Mr Harsha Paul VOL 6 ISSUE 7 [email protected] May–June, 2021 MJES in association with SACAA launches ‘ST ALOYSIUS COVID CARE CENTRE’ oneself from infection. T he Mangalore Jesuits Educational Society (MJES) in The Entrepreneurship and Consultancy Cell of St Aloys- association with St Aloysius College Alumni Association ius College (Autonomous) had taken initiative by (SACAA) launched ‘ST ALOYSIUS COVID CARE CEN- launching “St Aloysius Jaala Santhe” on 15th July 2020, TRE’ on Wednesday, 12 May 2021 and distributed Food brought together hundreds of rural entrepreneurs and Kits, Psychological Accompanying, Medicine, Health Fa- farmers in a WhatsApp group and facilitated buying and cilities and Essential Items to families of poor, migrant selling of these farmer products. workers, low wage labourers, and other poor families In the wake of the second wave of the pandemic hitting here to cope with the ongoing lockdown/pandemic. hard and the exponential spike in the spread of the vi- WHEN DOORS CLOSE AND HEARTS OPEN- The Covid-19 rus, MIES has put in place a centralized Covid Care crisis has brought to the fore not only our limitedness as Centre in the campus to facilitate quick and speedy re- human beings in the face of a pandemic but also the sad dressal of the issues and concerns of the people affected and infected by the virus leading to serious psychological and physical health hazards. The Centre will operate from the Gelge Hall (Main Auditorium) from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. -

Eligibility Circular No 205 of 2021 30.08.2021.Pdf

SAVITRIBAI PHULE PUNE UNIVERSITY (Formerly University of Pune) CIRCULAR No. 205 of 2021 INFORMATION REGARDING ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA FOR VARIOUS UNIVERSITY COURSES. Website : http://unipune.ac.in Dr. Nitin Karmalkar Hon’ble Vice-Chancellor, Savitribai Phule Pune University Dr. N. S. Umarani Hon’ble Pro-Vice-Chancellor, Savitribai Phule Pune University Eligibility Staff Members 1. Smt. M. S. Uttekar Asstt. Registrar Ph. : 25621180 2. Smt M. J. D’souza Asstt. Section Officer Ph. : 25621181 3. Smt. G. J. Zagade Assistant Ph. : 25621183 4. Smt. B. T. Patil Assistant Ph. : 25621182 5. Shri. B. C. Gajalwar Assistant Ph. : 25621187 INDEX Sr. No. Title Page No. 1.Circular .... 1-7 2. Course wise and yearwise No of Students Enrolled .... 8 3. Eligibility Equaivlence Letter & Government Resolution .... 9 - 19 for equivalence of I.T.I. 4. Faculty of Science and Technology 1. Science .... 20-38 2. Engineering .... 39-62 3. Technology .... 63-65 4. Architecture .... 66-67 5. Pharmaceutical Sciences .... 68-69 5. Faculty of Commerce and Management 1. Commerce .... 70-74 2. Management .... 75-78 6. Faculty of Humanities 1. Arts .... 79 - 83 2. Mental Moral & Social Sciences .... 84-89 3. Law .... 90 - 94 7. Faculty of Interdisciplinary Studies 1. Education .... 95 - 98 2. Physical Education .... 99 - 102 3. Library Science .... 103 4. Fine & Performing Arts .... 104 5. Social Work & Journalism .... 105 8. M.Phil. & Ph.D. .... 106-107 9. Definition .... 108-109 10. Instructions For the Final List of Eligibility Chart I .... 110-111 11. Annexure ‘A’ Eligibility Fee .... 112 12. Procedure for Migration Certificate Application .... 113 13. List of U.G.C Recognized University ... -

XIM University

XIM University Bhubaneswar An exclusive Guide by XIM University Reviews on Placements, Faculty & Facilities Check latest reviews and ratings on placements, faculty, facilities submitted by students & alumni. Reviews (Showing 20 of 131 reviews) Overall Rating (Out of 5) 4.1 Based o n 127 Verif ied Reviews Distribution of Rating >4-5 star 54% >3-4 star 37% >2-3 star 7% 1-2 star 2% Component Ratings (Out of 5) Placements 3.9 Infrastructure 4.4 Faculty & Course 4.3 Curriculum Crowd & Campus Life 4.4 Value for Money 3.6 The Verif ied badge indicates that the reviewer's details have been verified by Shiksha, and reviewers are bona f ide students of this college. These reviews and ratings have been given by students. Shiksha does not endorsed the same. Out of 131 published reviews, 127 reviews are verif ied. S Saksham Kumar Jha | B.Tech. (Hons.) in Computer Science and Engineering - Verified Batch of 2024 Reviewed on 3 Jul 2021 4.6 Placements 4 Infrastructure 4 Faculty & Course Curriculum 5 Crowd & Campus Life 5 It is absolutely a good place to pursue computer science and engineering in Odisha. Placements: As the first batch was passed out in 2021, the placements were provided in various MNCs. The majority of students got placed in companies like TCS, Tata Cliq, etc. Disclaimer: This PDF is auto-generated based on the information available on Shiksha as on 23-Sep-2021. Roles offered were SDEs in these companies. Students also got internships when pursuing their course. Infrastructure: Hostel facilities are top-notch here. -

Handbook & Calendar 2021-22

1 CONTENTS 1.XIM University -A Brief History 3 2. Timeline of XIM University 4 3. Vision, Mission and Values 6 4. Message from the Vice Chancellor 7 5. Board of Governors 8 6. Academic Council and Committees 10 7. Administrative Officers 12 8. Faculty of the University 14 9. Offices of the University 20 10.Rules and Regulations for Undergraduate Programs 23 11. Rules and Regulations for Postgraduate Programs 38 12. Rules and Regulations for Doctoral Programs 45 13.Student Counselling Cell 48 14. Guidelines for Disciplinary Measures-Examinations 49 15. Calendar 2021-22 56 16. Postgraduate Programs Examination Schedules-Term 68 17. Postgraduate Programs Examination Schedules-Semester 69 18.Undergraduate Programs Examination Schedule 71 2 XIM UNIVERSITY A Brief History The Government of Odisha and the Odisha Jesuit Society in 1987 entered a “Social Contract” which led to the establishment of the Xavier Institute of Management (XIMB). XIMB is acknowledged internationally as a world class business school which provides quality management Programs and develops futuristic managers and leaders with strong ethics and values. Owing to its unique quality, brand and academic rigour, in its endeavour to take up the tasks which are bold but necessary and which hitherto nobody has taken up XIMB, rose to meet the need for quality education in the state and country and founded the Xavier University. The Xavier University came into being with the Government of Odisha passing the Xavier University, Odisha, Act, 2013 and the New Campus was inaugurated on July 7, 2014. Subsequently, the stakeholders felt that the University would be better served by taking the name of its founding unit and the Xavier University, through an act of legislature, became the XIM University. -

49 ISTE National Annual Faculty Convention 2019

49th ISTE National Annual Faculty Convention 2019 29th November - 1st December, 2019 hnica ec l E T d n u i c s a e t s i i Theme: o r n C Organized by Siksha'O'Anusandhan (Deemed to be University) Khandagiri Square, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India Website: www.soa.ac.in About Indian Society for Technical Education (ISTE) The Indian Society for Technical Education (ISTE) is a non-profit making Society registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860. It was initially founded in 1941 as the Association of Principals of Technical Institutions (APTI) and later transformed as ISTE in 1968 with a view to enlarging its activities to advance the cause of technical education. The key objective of the ISTE is to assist and contribute to the education and development of top quality professional engineering needed by industry and other Organizations. Being the only national body of educators in the field of Engineering and Technology ISTEendeavors to effectively contribute to various mission of the Government. It is well associated with the Ministry of HRD, AICTE/DST/MIT/State Governments etc., for the programmes related to Technical Education.ISTE is actively involved in many activities conducted by All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE),New Delhi and National Board of Accreditation (NBA), New Delhi. It organizes an annual convention for faculty and students separately every year where a large number of technocrats, technical teachers, policy makers, experts from the industry etc. participate and interact. About Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (SOA) Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (SOA) is a multidisciplinary Deemed to be University established on 17th July 2007 u/s 3 of the UGC Act, 1956. -

Depositors to Get Upto Rs 5 Lakhs Within 90 Days If Banks Fail, Cabinet Clears Required Amendment Blinken, Jaishankar Have 'Goo

www Vol - 18 www Issue-20 www Bhubaneswar www 29 July, 2021 www Thursday ww Orissa Today email:[email protected], www Rs.2.00 People’s Voice [email protected] www Pages -8 RNI NO - ODIENG/2005/16409 For e paper : www.orissatodaynews. in [email protected] Depositors to get upto Rs 5 lakhs within 90 days CHSE Odisha 2021 Results To Be Declared On July 31 if banks fail, Cabinet clears required amendment Bhubaneswar, July New Delhi, July 28 (UNI) value, 50.9 per cent depos- companies. A similar 28(TNB): The Odisha gov- In a major relief to small its will be covered. treatment had to be given ernment today declared depositors, the Union In another major deci- for LLPs, said Thakur. the date on which results Cabinet on Wednesday sion, the Cabinet chaired The Cabinet also ap- for Class 12 Science and approved amendments to by Prime Minister proved Multilateral MoU Commerce students will be the Deposit Insurance and Narendra Modi cleared signed between interna- out. In a statement, the Credit Guarantee Corpora- amendment in Limited Li- tional financial service government stated the tion (DICGC) Act to en- ability Partnership (LLP) centres and multilateral Class 12 results of both sure account holders get Act to remove criminal agencies, International the streams assessed by back deposits upto Rs 5 provisions. The move will Organisation of Security the Council of Higher Sec- lakh within 90 days in case reduce compliance burden Commissions and Inter- ondary Education (CHSE) a distressed bank is put and improve ease of do- national Association of this year will be an- Last month, the Supreme scores in theory papers on under moratorium by Re- 5 lakhs of their money." in India. -

Consolidated List of All Universities

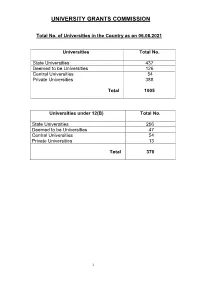

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION Total No. of Universities in the Country as on 06.08.2021 Universities Total No. State Universities 437 Deemed to be Universities 126 Central Universities 54 Private Universities 388 Total 1005 Universities under 12(B) Total No. State Universities 256 Deemed to be Universities 47 Central Universities 54 Private Universities 13 Total 370 1 S.No ANDHRA PRADESH Date/Year of Notification/ Establishment 1. Acharya N.G. Ranga Agricultural University, Lam, 1964 Guntur – 522 034,Andhra Pradesh (State University) 2. Acharya Nagarjuna University, Nagarjuna Nagar-522510, Dt. Guntur, 1976 Andhra Pradesh. (State University) 3. Adikavi Nannaya University, 25-7-9/1, Jayakrishnapuram, 2006 Rajahmundry – 533 105, East Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh. (State University) 4. Andhra University, Waltair, Visakhapatnam-530 003, Andhra Pradesh. 1926 (State University) 5. Bharatiya Engineering Science and Technology Innovation University, 17.02.2019 Gownivaripalli, Gorantla Mandal, Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh (Private University) 6. Central University of Andhra Pradesh, IT Incubation Centre Building, 05.08.2019 JNTU Campus, Chinmaynagar, Anantapuramu, Andhra Pradesh- 515002 (Central University) 7. Central Tribal University of Andhra Pradesh, Kondakarakam, 05.08.2019 Vizianagaram, Andhra Pradesh 535008 (Central University) 8. Centurion University of Technology and Management, Gidijala Junction, 23.05.2017 Anandapuram Mandal, Visakhapatnam – 531173, Andhra Pradesh. (Private University) 9. Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University, Plot No. 116, Sector 2008 11 MVP Colony, Visakhapatnam – 530 017, Andhra Pradesh. (State University) 10. Dr. Abdul Haq Urdu University, Kurnool- 518001, Andhra Pradesh 14.12.2018 (State University) 11. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University, Etcherla, Dt. Srikakulam-532410, 2008 Andhra Pradesh. (State University) 12. Dravidian University, Srinivasanam, -517 425, Chittoor District, 1997 Andhra Pradesh. -

Iipa Webinar Series

IIPA WEBINAR SERIES An Initiative on Flagship Schemes of Government of India by IIPA Smart city mission Organised by IIPA Odisha Regional Branch (25 August, 2021 at 3.00 P.M. ) Opening Remarks Welcome Address Theme Introduction Shri Surendra Nath Tripathi , IAS (Retd) Shri Sarat Chandra Misra, IPS (Retd) Dr. Gadadhara Mohapatra Director General, IIPA, New Delhi Chairman, IIPA Odisha Regional Branch Assistant Professor IIPA, New Delhi Key Speakers Vote of Thanks Prof. Tathagat Chatterjee Dr. Umamaheshwaran Rajasekar Shri Sanjay Singh, IAS, Commissioner Shri Ashok Kumar Mohapatra, OFS (Retd.) Professor of Urban Management & Chair, Urban Resilience at NIUA of Bhubaneswar Municipal Hony. Secretary, IIPA Governance, XIM Univ, Bhubaneswar Corporation (BMC), CEO Odisha Regional Branch Bhubaneswar Smart City Mission Link to join: https://iipa.webex.com/iipa/j.php?MTID=m264bc24a6d4d36a3844a4eeaebe8a245 Supported by INDIAN INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION, NEW DELHI SHRI SURENDRA NATH TRIPATHI, IAS (Retd.) SHRI SURENDRA NATH TRIPATHI, IAS(R) was an IAS officer of 1985 batch (Odisha Cadre). An MA in Political Science from Allahabad University and MBA in Public Policy from Slovenia, Sh Tripathi is a highly seasoned Civil Servant with a true academic flavour. Before joining IAS, he had been Lecturer in Allahabad University. He took over the charge of Director IIPA in April 2019 while he was still holding the charge of Secretary, Ministry of Parliamentary Affairs, Govt. of India. Before that he adorned many important positions both in Govt of India as also in the Govt. of Odisha. He worked as AS&FA in Union Ministry of Agriculture and Joint Secretary as also Development Commissioner in MSME.