Human Thelaziasis, Europe, 2005–2006 No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

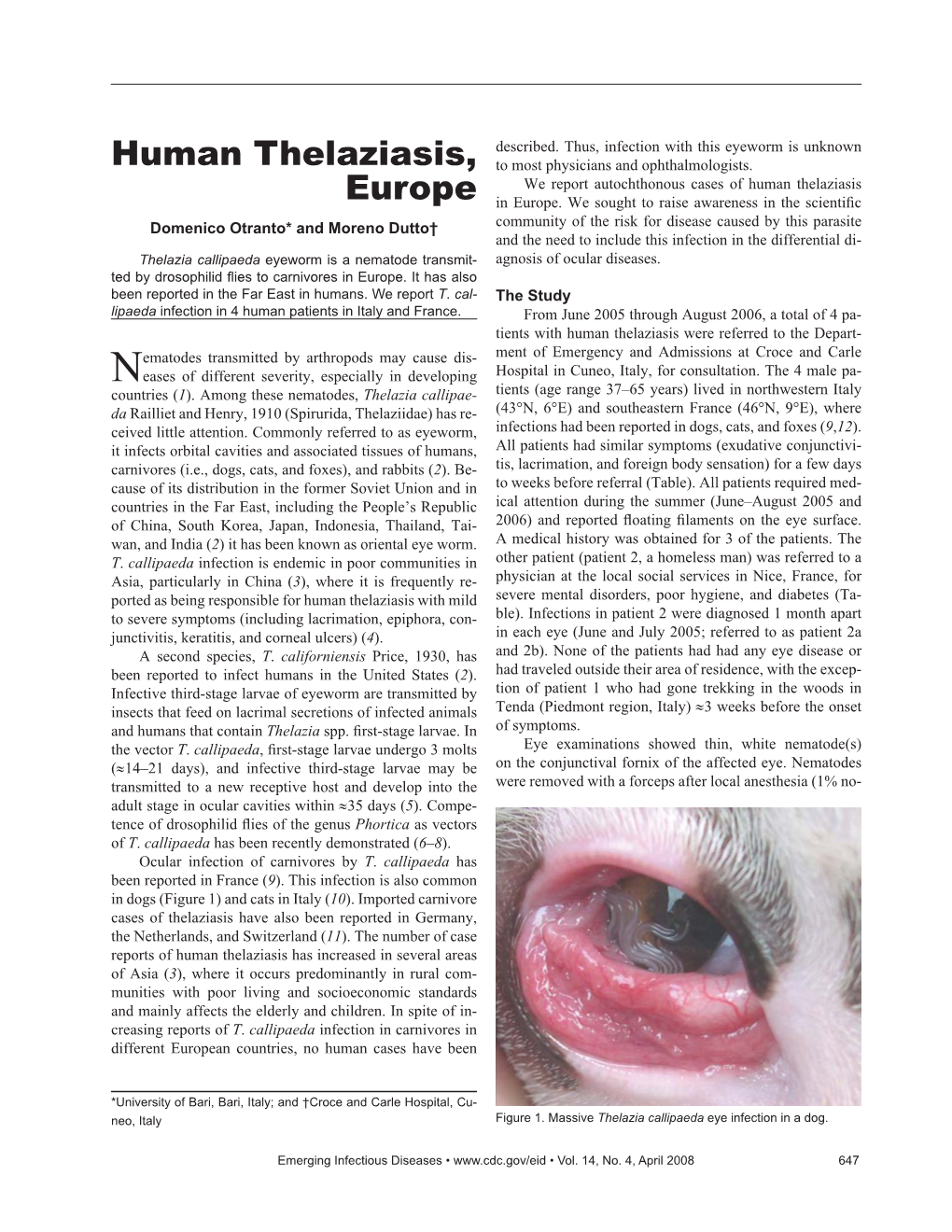

Recommended publications

-

Epidemiology of Filariasis in India * N

Bull. Org. mond. Sante 1957, 16, 553-579 Bull. Wld Hith Org. EPIDEMIOLOGY OF FILARIASIS IN INDIA * N. G. S. RAGHAVAN, B.A., M.B., B.S. Assistant Director, Malaria Institute of India, Delhi, India SYNOPSIS The author reviews the history of filarial infections in India and discusses factors affecting the filariae, their vectors, and the human reservoir of infection. A detailed description is given of techniques for determining the degree of infection, disease and endemicity of filariasis in a community, and aspects which require further study are indicated. Filarial infections have been recorded in India as early as the sixth century B.C. by the famous physician Susruta in Chapter XII of the Susruta Sanihita (quoted by Menon 48). The description of the signs and symptoms of this disease by Madhavakara (seventh century A.D.) in his treatise Madhava Nidhana (Chapter XXXIX), holds good even today. More recently, Clarke in 1709 called elephantiasis of the legs in Cochin, South India, "Malabar legs " (see Menon 49). Lewis 38 in India discovered microfilariae in the peripheral blood. Between 1929 and 1946 small-scale surveys have been carried out, first by Korke 35, 36 and later by Rao 63-65 under the Indian Council of Medical Research (Indian Research Fund Association), and others, at Saidapet, by workers at the King Institute, Guindy, Madras (King et al.33). The studies in the epidemiology of filariasis in Travancore by Iyengar (1938) have brought out many important points in regard to Wuchererian infections, especially W. malayi. The first description of MJ. malayi in India was made by Korke 35 in Balasore District, Orissa State; the credit for describing the adult worms of this infection is due to Rao & Maplestone.8 The discovery of the garden lizard Calotes versicolor with a natural filarial infection - Conispiculum guindiensis - (Pandit, Pandit & Iyer 53) in Guindy led to studies in experimental transmission which threw some interesting light on comparative development (Menon & Ramamurti ;49 Menon, Ramamurti & Sundarasiva Rao 50). -

Effects of Parasites on Marine Maniacs

EFFECTS OF PARASITES ON MARINE MANIACS JOSEPH R. GERACI and DAVID J. ST.AUBIN Department of Pathology Ontario Veterinary College University of Guefph Guelph, Ontario Canada INTRODUCTION Parasites of marine mammals have been the focus of numerous reports dealing with taxonomy, distribution and ecology (Defyamure, 1955). Descriptions of associated tissue damage are also available, with attempts to link severity of disease with morbidity and mortality of individuals and populations. This paper is not intended to duplicate that Iiterature. Instead we focus on those organisms which we perceive to be pathogenic, while tempering some of the more exaggerated int~~retations. We deal with life cycles by emphasizing unusual adap~t~ons of selected organisms, and have neces- sarily limited our selection of the literature to highlight that theme. For this discussion we address the parasites of cetaceans---baleen whales (mysticetes), and toothed whales, dolphins and porpoises (odon- tocetes): pinnipeds-true seals (phocidsf, fur seals and sea Iions (otariidsf and walruses (adobenids); sirenians~anatees and dugongs, and the djminutive sea otter. ECTOPARASITES We use the term “ectoparasite’” loosely, when referring to organisms ranging from algae to fish which somehow cling to the surface of a marine mammal, and whose mode of attachment, feeding behavior, and relationship with the host or transport animal are sufficiently obscure that the term parasite cannot be excluded. What is clear is that these organisms damage the integument in some way. For example: a whale entering the coid waters of the Antarctic can acquire a yelIow film over its body. Blue whales so discoiored are known as “sulfur bottoms”. -

Proceedings of the Helminthological Society of Washington 51(2) 1984

Volume 51 July 1984 PROCEEDINGS ^ of of Washington '- f, V-i -: ;fx A semiannual journal of research devoted to Helminthohgy and all branches of Parasitology Supported in part by the -•>"""- v, H. Ransom Memorial 'Tryst Fund : CONTENTS -j<:'.:,! •</••• VV V,:'I,,--.. Y~v MEASURES, LENA N., AND Roy C. ANDERSON. Hybridization of Obeliscoides cuniculi r\ XGraybill, 1923) Graybill, ,1924 jand Obeliscoides,cuniculi multistriatus Measures and Anderson, 1983 .........:....... .., :....„......!"......... _ x. iXJ-v- 179 YATES, JON A., AND ROBERT C. LOWRIE, JR. Development of Yatesia hydrochoerus "•! (Nematoda: Filarioidea) to the Infective Stage in-Ixqdid Ticks r... 187 HUIZINGA, HARRY W., AND WILLARD O. GRANATH, JR. -Seasonal ^prevalence of. Chandlerellaquiscali (Onehocercidae: Filarioidea) in Braih, of the Common Grackle " '~. (Quiscdlus quisculd versicolor) '.'.. ;:,„..;.......„.;....• :..: „'.:„.'.J_^.4-~-~-~-<-.ii -, **-. 191 ^PLATT, THOMAS R. Evolution of the Elaphostrongylinae (Nematoda: Metastrongy- X. lojdfea: Protostrongylidae) Parasites of Cervids,(Mammalia) ...,., v.. 196 PLATT, THOMAS R., AND W. JM. SAMUEL. Modex of Entry of First-Stage Larvae ofr _^ ^ Parelaphostrongylus odocoilei^Nematoda: vMefastrongyloidea) into Four Species of Terrestrial Gastropods .....:;.. ....^:...... ./:... .; _.... ..,.....;. .-: 205 THRELFALL, WILLIAM, AND JUAN CARVAJAL. Heliconema pjammobatidus sp. n. (Nematoda: Physalbpteridae) from a Skate,> Psammobatis lima (Chondrichthyes: ; ''•• \^ Rajidae), Taken in Chile _... .„ ;,.....„.......„..,.......;. ,...^.J::...^..,....:.....~L.:....., -

Cha Kuna Taiteit Un Chitan Dalam Menit

CHA KUNA TAITEIT US009943590B2UN CHITAN DALAM MENIT (12 ) United States Patent ( 10 ) Patent No. : US 9 ,943 ,590 B2 Harn , Jr . et al. (45 ) Date of Patent: Apr . 17 , 2018 (54 ) USE OF LISTERIA VACCINE VECTORS TO 5 ,679 ,647 A 10 / 1997 Carson et al. 5 ,681 , 570 A 10 / 1997 Yang et al . REVERSE VACCINE UNRESPONSIVENESS 5 , 736 , 524 A 4 / 1998 Content et al. IN PARASITICALLY INFECTED 5 ,739 , 118 A 4 / 1998 Carrano et al . INDIVIDUALS 5 , 804 , 566 A 9 / 1998 Carson et al. 5 , 824 ,538 A 10 / 1998 Branstrom et al. (71 ) Applicants : The Trustees of the University of 5 ,830 ,702 A 11 / 1998 Portnoy et al . Pennsylvania , Philadelphia , PA (US ) ; 5 , 858 , 682 A 1 / 1999 Gruenwald et al. 5 , 922 , 583 A 7 / 1999 Morsey et al. University of Georgia Research 5 , 922 ,687 A 7 / 1999 Mann et al . Foundation , Inc. , Athens, GA (US ) 6 ,004 , 815 A 12/ 1999 Portnoy et al. 6 ,015 , 567 A 1 /2000 Hudziak et al. (72 ) Inventors: Donald A . Harn , Jr. , Athens, GA (US ) ; 6 ,017 ,705 A 1 / 2000 Lurquin et al. Yvonne Paterson , Philadelphia , PA 6 ,051 , 237 A 4 / 2000 Paterson et al . 6 ,099 , 848 A 8 / 2000 Frankel et al . (US ) ; Lisa McEwen , Athens, GA (US ) 6 , 287 , 556 B1 9 / 2001 Portnoy et al. 6 , 306 , 404 B1 10 /2001 LaPosta et al . ( 73 ) Assignees : The Trustees of the University of 6 ,329 ,511 B1 12 /2001 Vasquez et al. Pennsylvania , Philadelphia , PA (US ) ; 6 , 479 , 258 B1 11/ 2002 Short University of Georgia Research 6 , 504 , 020 B1 1 / 2003 Frankel et al . -

A Pediatric Case of Thelaziasis in Korea

ISSN (Print) 0023-4001 ISSN (Online) 1738-0006 Korean J Parasitol Vol. 54, No. 3: 319-321, June 2016 ▣ CASE REPORT http://dx.doi.org/10.3347/kjp.2016.54.3.319 A Pediatric Case of Thelaziasis in Korea Chung Hyuk Yim1, Jeong Hee Ko1, Jung Hyun Lee1, Yu Mi Choi1, Won Wook Lee1, Sang Ki Ahn2, Myoung Hee Ahn3, Kyong Eun Choi1 Departments of 1Pediatrics and 2Ophthalmology, Gwangmyeong Sungae Hospital, Gwangmyeong 14241, Korea; 3Department of Environmental Biology and Medical Parasitology, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul 04763, Korea Abstract: In the present study, we intended to report a clinical pediatric case of thelaziasis in Korea. In addition, we briefly reviewed the literature on pediatric cases of thelaziasis in Korea. In the present case, 3 whitish, thread-like eye-worms were detected in a 6-year-old-boy living in an urban area and contracted an ocular infection known as thelaziasis inciden- tally during ecological agritainment. This is the first report of pediatric thelaziasis in Seoul after 1995. Key words: Thelazia callipaeda, thelaziasis, eye-worm, pediatric ocular parasite, ecological agritainment INTRODUCTION conservative treatment with intravenous cefotaxime 150 mg/ kg/day and levofloxacin eye drops after an ophthalmologic ex- Thelazia callipaeda is an uncommon ocular parasite in Asia. amination. The results of the blood test on admission were as The first human case was described in 1917 by Stuckey [1], follows: white blood cell count 13,210/μl, C-reactive protein and the first human infection in Korea was reported by Naka- 7.191 mg/dl, and eosinophil count 0%. Parasitic, helminth da in 1934 [2]. -

The Helminthological Society of Washinqton I

. Volume 46 1979 Number 2 PROCEEDINGS The Helminthological Society %Hi.-s'^ k •''"v-'.'."'/..^Vi-":W-• — • '.'V ' ;>~>: vf-; • ' ' / '••-!' . • '.' -V- o<•' fA • WashinQto" , ' •- V ' ,• -. " ' <- < 'y' : n I •;.T'''-;«-''•••.'/ v''.•'••/••'; •;•-.-•• : ' . -•" 3 •/"-:•-:•-• ..,!>.>>, • >; A semiannual: journal Jof research devoted to Helminthology and a// branches of Paras/fo/ogy ,I ^Supported in part by<the / ^ ^ ;>"' JBrayton H. Ransom^Memorial TrustJiund /^ v ''•',''•'•- '-- ^ I/ •'/"! '' " '''-'• ' • '' * ' •/ -"."'• Subscription $i;iB.OO a Volume; foreign, $1 ?1QO /' rv 'I, > ->\ ., W./JR. Polypocephalus sp. (CeModa; Lecanieephalidae): ADescrip- / ^xtion, of .Tentaculo-PJerocercoids .'from Bay Scallops of the Northeastern Gulf ( ,:. ••-,' X)f Mexico^-— u-':..-., ____ :-i>-.— /— ,-v-— -— ;---- ^i--l-L4^,- _____ —.—.;—— -.u <165 r CAREER, GEORGE^ J.^ANDKENNETI^: C, CORKUM. 'Life jpycle (Studies of Three Di- .:•';' genetic; Trpmatodes, Including /Descriptions of Two New' Species (Digenea: ' r vCryptpgonirnidae) ,^.: _____ --—cr? ..... ______ v-^---^---<lw--t->-7----^--'r-- ___ ~Lf. \8 . ; HAXHA WAY, RONALD P, The Morphology of Crystalline Inclusions in, Primary Qo: ^ - r ',{••' cylesfafiAspidogaJter conchicola von Baer,;1827((Trematoda: A^pidobpthria)— : ' 201 HAYUNGA, EUGENE ,G. (The Structure and Function of the GlaJids1! of .. Three .Carypphyllid T;ape\y,orms_Jr-_-_.--_--.r-_t_:_.l..r ____ ^._ ______ ^..—.^— —....: rJ7l ' KAYT0N , ROBERT J . , PELANE C. I^RITSKY, AND RICHARD C. TbaiAS. Rhabdochona /• ;A ; ycfitostomi sp. n. (Nematoifja: Rhaibdochonidae)"from the-Intestine of Catdstomusi ' 'i -<•'• ' spp.XGatostpmjdae)— ^ilL.^—:-;..-L_y— 1..:^^-_— -L.iv'-- ___ -—- ?~~ -~—:- — -^— '— -,--- X '--224- -: /McLoUGHON, D. K. AND M:JB. CHUTE: \ tenellq.in Chickens:, Resistance to y a Mixture .of Suifadimethoxine and'Ormetpprim (Rofenaid) ,___ _ ... .. ......... ^...j.. , 265 , M, C.-AND RV A;. KHAN. Taxonomy, Biology, and Occurrence of Some " Manhe>Lee^ches in 'Newfoundland Waters-i-^-\---il.^ , R. -

STUDIES on the LIFE HISTORY of RICTULARIA COLORADENSIS HALL, 1916 (NEMATODA: THELAZIIDAE), a PARASITE of Phtomyscus LEUCOPPS NOVEBORACENSIS (FISCHER)

STUDIES ON THE LIFE HISTORY OF RICTULARIA COLORADENSIS HALL, 1916 (NEMATODA: THELAZIIDAE), A PARASITE OF PHtoMYSCUS LEUCOPPS NOVEBORACENSIS (FISCHER) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio S tate U niversity Bbr VERNON HARVEY OSWALD, B. S ., 11. A. ***** The Ohio State University 1956 Approved by: f Department of Zoology and [ y Entomology ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study was accomplished through the direct and indirect assistance of many of the faculty members, fellow students, and technical personnel in the Department of Zoology and Entomology of The Ohio State University. The author wishes to thank Dr. Josef N. Knull and Mr. Richard D. Alexander of the Department of Zoology and Entomology for identifying ground beetles and field crickets, respec tively, which were used in th is study. Dr. Edward Thomas of the Ohio State Museum, Columbus, kindly identified wood roaches and camel crickets for the author. Special thanks also go to Mr. Donal (3. Myer for help in collecting material and to Mr. John L. Crites who was concurrently working on the life history of Cruzla americana and who offered many suggestions on techniques which were used by the author. Dr. William H. Coil, a Muellhaupt Scholar in the Depart ment, took an active part in collecting material and is also respon sible for the photomicrographs included in this work. Lastly, the writer wishes to acknowledge the many helpful suggestions and c riti cisms given hy his adviser, Dr. Joseph N. Miller of the Department of Zoology and Entosology. - i i TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... -

Worms, Germs, and Other Symbionts from the Northern Gulf of Mexico CRCDU7M COPY Sea Grant Depositor

h ' '' f MASGC-B-78-001 c. 3 A MARINE MALADIES? Worms, Germs, and Other Symbionts From the Northern Gulf of Mexico CRCDU7M COPY Sea Grant Depositor NATIONAL SEA GRANT DEPOSITORY \ PELL LIBRARY BUILDING URI NA8RAGANSETT BAY CAMPUS % NARRAGANSETT. Rl 02882 Robin M. Overstreet r ii MISSISSIPPI—ALABAMA SEA GRANT CONSORTIUM MASGP—78—021 MARINE MALADIES? Worms, Germs, and Other Symbionts From the Northern Gulf of Mexico by Robin M. Overstreet Gulf Coast Research Laboratory Ocean Springs, Mississippi 39564 This study was conducted in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA, Office of Sea Grant, under Grant No. 04-7-158-44017 and National Marine Fisheries Service, under PL 88-309, Project No. 2-262-R. TheMississippi-AlabamaSea Grant Consortium furnish ed all of the publication costs. The U.S. Government is authorized to produceand distribute reprints for governmental purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation that may appear hereon. Copyright© 1978by Mississippi-Alabama Sea Gram Consortium and R.M. Overstrect All rights reserved. No pari of this book may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the author. Primed by Blossman Printing, Inc.. Ocean Springs, Mississippi CONTENTS PREFACE 1 INTRODUCTION TO SYMBIOSIS 2 INVERTEBRATES AS HOSTS 5 THE AMERICAN OYSTER 5 Public Health Aspects 6 Dcrmo 7 Other Symbionts and Diseases 8 Shell-Burrowing Symbionts II Fouling Organisms and Predators 13 THE BLUE CRAB 15 Protozoans and Microbes 15 Mclazoans and their I lypeiparasites 18 Misiellaneous Microbes and Protozoans 25 PENAEID -

Internal Parasites of Sheep and Goats

Internal Parasites of Sheep and Goats BY G. DIKMANS AND D. A. SHORB ^ AS EVERY SHEEPMAN KNOWS, internal para- sites are one of the greatest hazards in sheep production, and the problem of control is a difficult one. Here is a discussion of some 40 of these parasites, including life histories, symptoms of infestation, medicinal treat- ment, and preventive measures. WHILE SHEEP, like other farm animals, suffer from various infectious and noiiinfectious diseases, the most serious losses, especially in farm flocks, are due to internal parasites. These losses result not so much from deaths from gross parasitism, although fatalities are not infre- quent, as from loss of condition, unthriftiness, anemia, and other effects. Devastating and spectacular losses, such as were formerly caused among swine by hog cholera, among cattle by anthrax, and among horses by encephalomyelitis, seldom occur among sheep. Losses due to parasites are much less seni^ational, but they are con- stant, and especially in farai flocks they far exceed those due to bacterial diseases. They are difficult to evaluate, however, and do not as a rule receive the attention they deserve. The principal internal parasites of sheep and goats are round- worms, tapeworms, flukes, and protozoa. Their scientific and com- mon names and their locations in the host are given in table 1. Another internal parasite of sheep, the sheep nasal fly, the grubs of which develop in the nasal pasisages and head sinuses, is discussed at the end of the article. ^ G. Dikmans is Parasitologist and D. A. Sborb is Assistant Parasitologist, Zoological Division, Bureau of Animal Industry. -

A Case of Human Thelaziasis from Himachal Pradesh

Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology, (2006) 24 (1):67-9 Case Report A CASE OF HUMAN THELAZIASIS FROM HIMACHAL PRADESH *A Sharma, M Pandey, V Sharma, A Kanga, ML Gupta Abstract Small, chalky-white, threadlike, motile worms were isolated from the conjunctival sac of a 32 year-old woman residing in the Himalaya mountains. They were identified as both male and female worms of Thelazia callipaeda. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second case report of human thelaziasis from India. Key words: Human thelaziasis, Oriental eyeworm Thelazia callipaeda was first reported by Railliet and Case Report Henry in 1910 from a Chinese dog and it is also known as Oriental eyeworm. The first human case was reported by During autumn of 2004 a 32 year old woman from a rural Stucky in 1917, who extracted four worms from the eye of a mountainous region presented with the complaint of small, coolie in Peiping, China. Since then a number of species of white, threadlike worms in her right eye. She was suffering eyeworm have been reported in certain animals and birds from with foreign body sensation and itching in her right eye for a different countries of the world.1 The two important species few days. On looking in the mirror, she noticed moving worms infecting human eye are Thelazia callipaeda and, rarely, in her eye. She could remove three worms with the help of a Thelazia californiensis. T. callipaeda is found in China, India, cotton wick. On her visit to the hospital, on examination, no Thailand, Korea, Japan and Russia. -

Studies on the Interactions of Thelazia Sp., Introduced Eyeworm Parasites of Cattle, with Their Definitive and Intermediate Hosts in Massachusetts

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1979 Studies on the interactions of Thelazia sp., introduced eyeworm parasites of cattle, with their definitive and intermediate hosts in Massachusetts. Christopher John Geden University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Geden, Christopher John, "Studies on the interactions of Thelazia sp., introduced eyeworm parasites of cattle, with their definitive and intermediate hosts in Massachusetts." (1979). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 3032. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/3032 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDIES ON THE INTERACTIONS OF THELAZIA SP. , INTRODUCED EYEWORM PARASITES OF CATTLE, WITH THEIR DEFINITIVE AND INTERMEDIATE HOSTS IN MASSACHUSETTS A Thesis Presented By CHRISTOPHER JOHN GEDEN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE September 1979 Entomology STUDIES ON THE INTERACTIONS OF THELAZIA SP. , INTRODUCED EYEWORM PARASITES OF CATTLE, WITH THEIR DEFINITIVE AND INTERMEDIATE HOSTS IN MASSACHUSETTS A Thesis Presented By CHRISTOPHER JOHN GEDEN Approved as to style and content by* 6 v- a (Dr. John G. Stoffolano, Jr.), Chairperson of Committee (Dr, John D, Edman), Member / qU± ~ ft ^ (Dr, Chih-Ming Yin), Member' ii DEDICATION To my parents, George F. and Doris L. Geden, for their many years of encouragement, love, and emotional support. -

Guide to the Parasites of Fishes of Canada Part V: Nematoda

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Biology Faculty Publications Biology 2016 ZOOTAXA: Guide to the Parasites of Fishes of Canada Part V: Nematoda Hisao P. Arai Pacific Biological Station John W. Smith Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/biol_faculty Part of the Biology Commons, and the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Arai, Hisao P., and John W. Smith. Zootaxa: Guide to the Parasites of Fishes of Canada Part V: Nematoda. Magnolia Press, 2016. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Biology at Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zootaxa 4185 (1): 001–274 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4185.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:0D054EDD-9CDC-4D16-A8B2-F1EBBDAD6E09 ZOOTAXA 4185 Guide to the Parasites of Fishes of Canada Part V: Nematoda HISAO P. ARAI3, 5 & JOHN W. SMITH4 3Pacific Biological Station, Nanaimo, British Columbia V9R 5K6 4Department of Biology, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3C5. E-mail: [email protected] 5Deceased Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by K. DAVIES (Initially edited by M.D.B. BURT & D.F. McALPINE): 5 Apr. 2016; published: 8 Nov. 2016 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 HISAO P. ARAI & JOHN W.