4. the Fresco of the Anastasis in the Chora Church

Total Page:16

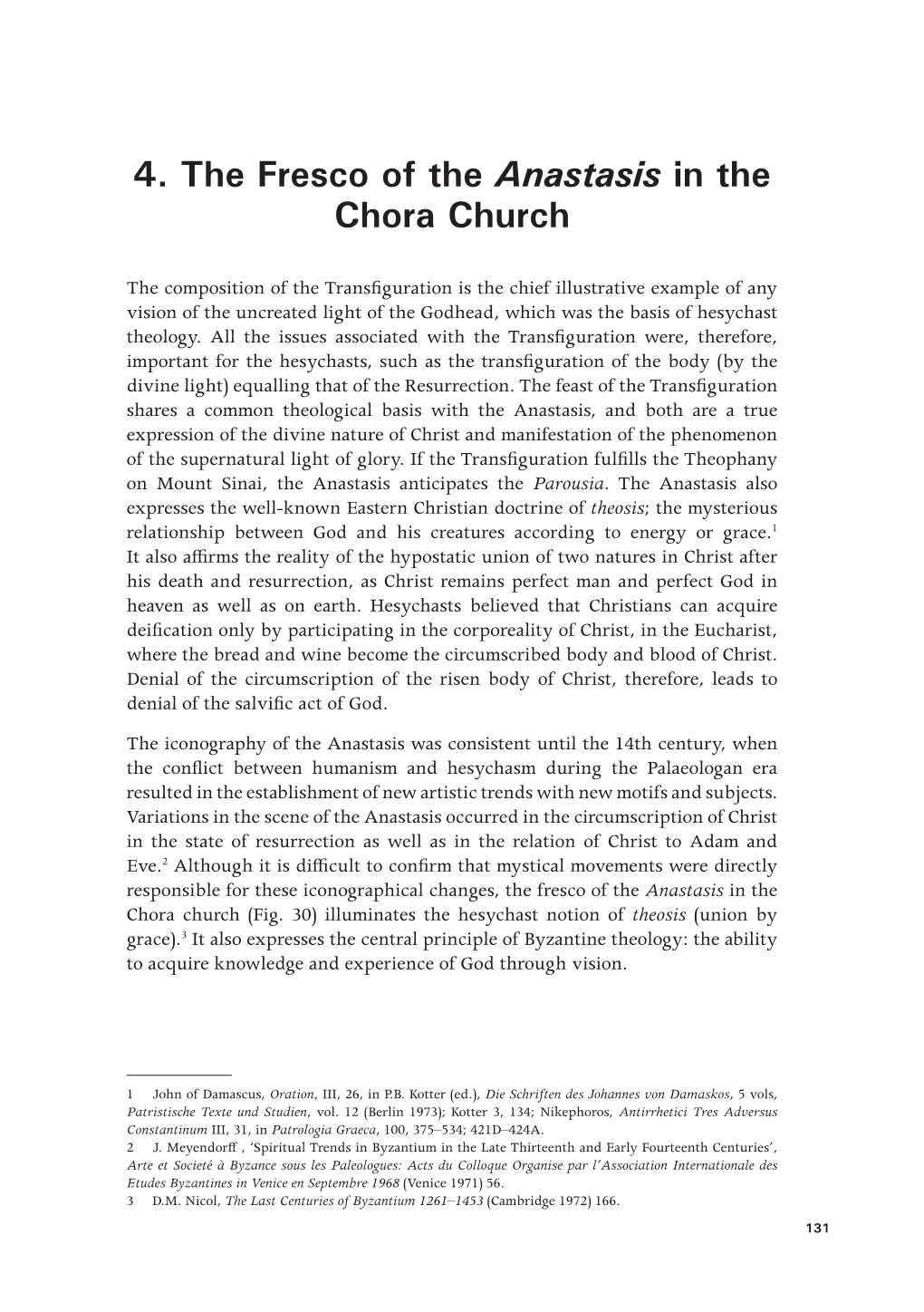

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

06.07 Holy Saturday and Harrowing of Hell.Indd

Association of Hebrew Catholics Lecture Series The Mystery of Israel and the Church Spring 2010 – Series 6 Themes of the Incarnation Talk #7 Holy Saturday and the Harrowing of Hell © Dr. Lawrence Feingold STD Associate Professor of Theology and Philosophy Kenrick-Glennon Seminary, Archdiocese of St. Louis, Missouri Note: This document contains the unedited text of Dr. Feingold’s talk. It will eventually undergo final editing for inclusion in the series of books being published by The Miriam Press under the series title: “The Mystery of Israel and the Church”. If you find errors of any type, please send your observations [email protected] This document may be copied and given to others. It may not be modified, sold, or placed on any web site. The actual recording of this talk, as well as the talks from all series, may be found on the AHC website at: http://www.hebrewcatholic.net/studies/mystery-of-israel-church/ Association of Hebrew Catholics • 4120 W Pine Blvd • Saint Louis MO 63108 www.hebrewcatholic.net • [email protected] Holy Saturday and the Harrowing of Hell Whereas the events of Good Friday and Easter Sunday Body as it lay in the tomb still the Body of God? Yes, are well understood by the faithful and were visible in indeed. The humanity assumed by the Son of God in the this world, the mystery of Holy Saturday is obscure to Annunciation in the womb of the Blessed Virgin is forever the faithful today, and was itself invisible to our world His. The hypostatic union was not disrupted by death. -

Turkey: the World’S Earliest Cities & Temples September 14 - 23, 2013 Global Heritage Fund Turkey: the World’S Earliest Cities & Temples September 14 - 23, 2013

Global Heritage Fund Turkey: The World’s Earliest Cities & Temples September 14 - 23, 2013 Global Heritage Fund Turkey: The World’s Earliest Cities & Temples September 14 - 23, 2013 To overstate the depth of Turkey’s culture or the richness of its history is nearly impossible. At the crossroads of two continents, home to some of the world’s earliest and most influential cities and civilizations, Turkey contains multi- tudes. The graciousness of its people is legendary—indeed it’s often said that to call a Turk gracious is redundant—and perhaps that’s no surprise in a place where cultural exchange has been taking place for millennia. From early Neolithic ruins to vibrant Istanbul, the karsts and cave-towns of Cappadocia to metropolitan Ankara, Turkey is rich in treasure for the inquisi- tive traveler. During our explorations of these and other highlights of the coun- FEATURING: try, we will enjoy special access to architectural and archaeological sites in the Dan Thompson, Ph.D. company of Global Heritage Fund staff. Director, Global Projects and Global Heritage Network Dr. Dan Thompson joined Global Heritage Fund full time in January 2008, having previously conducted fieldwork at GHF-supported projects in the Mirador Basin, Guatemala, and at Ani and Çatalhöyük, both in Turkey. As Director of Global Projects and Global Heri- tage Network (GHN), he oversees all aspects of GHF projects at the home office, manages Global Heritage Network, acts as senior editor of print and web publica- tions, and provides support to fundraising efforts. Dan has BA degrees in Anthropology/Geography and Journalism, an MA in Near Eastern Studies from UC Berkeley, and a Ph.D. -

Great Commission’ and the Tendency of Wesley’S Speech About God the Father

“THE PECULIAR BUSINESS OF AN APOSTLE” The ‘Great Commission’ and the Tendency of Wesley’s Speech about God the Father D. Lyle Dabney Marquette University Written for the Systematic Theology Working Group of the Twelfth Oxford Institute of Methodist Theological Studies meeting at Christ Church College, Oxford, England August 12-21, 2007 In focusing the general call concerning papers for this working group, Craig Keen and Sarah Lancaster began by instructing us to attend to the ecclesiological significance and broader theological ramifications of the calling and mission of the church, which the Creed of Nicea describes not only as ‘one, holy, [and]catholic,’ but also as ‘apostolic.’ We ask in particular that members of this working group consider the Great Commission that closes the Gospel of Matthew. In sum, our conveners have asked us to concentrate our work on the character of the Christian community as ‘apostolic,’ i.e., as defined by the mission of word and deed that Christ has bequeathed to his disciples. Following those instructions, let me introduce my topic with the familiar words of the Great Commission to which they refer, and of the pericope that gives it context. Now the eleven disciples went to Galilee, to the mountain to which Jesus had directed them. When they saw him, they worshiped him; but some doubted. And Jesus came and said to them, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you. -

Conversion of Kariye Museum to Mosque in Turkey

Conversion of Kariye Museum to Mosque in Turkey August 24, 2020 A month after turning the iconic Hagia Sophia museum, originally a cathedral, into a mosque, Turkey’s government has decided to convert another Byzantine monument in Istanbul, which has been a museum for over 70 years, into a working mosque. Late last year, the Council of State, the highest administrative court in Turkey, had removed legal hurdles for the Chora (Kariye) museum’s reconversion into a mosque. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose Islamist AK Party has long called for the reconversion of the Ottoman-era mosques that were secularised by Kemalists, signed a decree, transferring the management of the medieval monument to the Directorate of Islamic Affairs. Kariye Museum Originally built in the early 4th century as a chapel outside the city walls of Constantinople built by Constantine the Great, the Chora Church was one of the oldest religious monuments of the Byzantine era and of eastern Orthodox Christianity. It’s believed that the land where the chapel was built was the burial site of Babylas of Antioch, a saint of Eastern Christians, and his disciples. Emperor Justinian I, who built Hagia Sophia during 532-537, reconstructed Chora after the chapel had been ruined by an earthquake. Since then, it has been rebuilt many times. Today’s structure is considered to be at least 1,000 years old. Maria Doukaina, the mother-in-law of Emperor Alexios Komnenos I, launched a renovation project in the 11th century. She rebuilt Chora into the shape of a quincunx, five circles arranged in a cross which was considered a holy shape during the Byzantine era. -

The Little Metropolis at Athens 15

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses 2011 The Littleetr M opolis: Religion, Politics, & Spolia Paul Brazinski Bucknell University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Brazinski, Paul, "The Little eM tropolis: Religion, Politics, & Spolia" (2011). Honors Theses. 12. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/12 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Paul A. Brazinski iv Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge and thank Professor Larson for her patience and thoughtful insight throughout the writing process. She was a tremendous help in editing as well, however, all errors are mine alone. This endeavor could not have been done without you. I would also like to thank Professor Sanders for showing me the fruitful possibilities in the field of Frankish archaeology. I wish to thank Professor Daly for lighting the initial spark for my classical and byzantine interests as well as serving as my archaeological role model. Lastly, I would also like to thank Professor Ulmer, Professor Jones, and all the other Professors who have influenced me and made my stay at Bucknell University one that I will never forget. This thesis is dedicated to my Mom, Dad, Brian, Mark, and yes, even Andrea. Paul A. Brazinski v Table of Contents Abstract viii Introduction 1 History 3 Byzantine Architecture 4 The Little Metropolis at Athens 15 Merbaka 24 Agioi Theodoroi 27 Hagiography: The Saints Theodores 29 Iconography & Cultural Perspectives 35 Conclusions 57 Work Cited 60 Appendix & Figures 65 Paul A. -

Istanbul, Not Constantinople: a Global City in Context

Istanbul, Not Constantinople: A Global City in Context ASH 3931 Section 8ES5 / EUH 3931 Section 8ES5 / EUS 3930 Section 19ES Monday, Wednesday, Friday periods 5 Virtual office hours T R 1-3pm University of Florida Fall 2020 Course Description This is a course about why Istanbul is a global city and how it remains to be one. This particular city makes a central node in all the five utilities of global flow – defined by theorist Arjun Appadurai as ethnoscapes, technoscapes, financescapes, mediascapes, and ideoscapes. In this course, we take a multidisciplinary, transhistorical look at the city in three parts: 1) Pre-modern political, religious, commercial, and military exchanges that reflected and shaped the city landscape, 2) Modern cultural norms, natural disasters, and republican formations that caused the city to shrink on a logical and dramatic scale, and, 3) Artists, athletes, politicians, and soldiers that claimed the space in the city. Overlapping and standing alone at times, the topics to be explored likewise relate to various topics, including authority, civic nationalism, gender, migration, poverty, public health, and religion all in traditional and national, global and local ways. Beside others, students interested in European Studies, International Studies, Religious Studies, and Middle Eastern Studies are welcome and encouraged to join this survey course. Sophomore standing or the instructor’s approval is a prerequisite. Course Objectives By the end of the course, you should be able to: - Recognize and analyze the significance of Istanbul in discussions about geography, history, culture, politics, and sociology, - Present an informed understanding of global cities in comparative context, - Discuss specific developments that correlate Istanbul to political, social, economic, and other developments in the larger world, and, - Reconsider the nuanced dynamics that created and transformed Istanbul across time. -

A General Semantics View of the Changing Perceptions of Christ

A General Semantics View of the Changing Perceptions of Christ RaeAnn Burton, Beth Maryott, & Megan O’Byrne "A General Semantics View of the Changing Perceptions of Christ," presented by RaeAnn Burton, Beth Maryott, and Megan O'Byrne, explores the American views of Jesus Christ perceptually and visually. It includes traditional, pictorial representations and reactions to nontraditional or New Age portrayals. The paper also addresses perceptual revolution in the minds of Americans regarding Jesus Christ. The presentation then shows the relationship of these concepts to general semantics principles. * * * Modern Portrayals of Jesus in Works of Art RaeAnn Burton University of Nebraska at Kearney "Modern Portrayals of Jesus in Works of Art" is a paper addressing modern depictions of Jesus that stray from the traditional portrayals of Christ. New images of Jesus in paintings by Stephen Sawyer and Janet McKenzie are described to show how the image of Jesus is changing in the 21st century. Examples of sculptures and humorous pieces that depict Jesus in a modern fashion are also described. Last, the relationship between these modern portrayals of Jesus and general semantics is discussed. It is noted that every depiction of Christ, whether traditional or nontraditional, is an assumption. Depictions of Jesus are changing in the 21st century. This paper describes some of the changes in works of art and relates the changes to the study of general semantics. Introduction For centuries the image of Jesus’ physical appearance has been etched into people’s minds. Children learn in Sunday school at a young age what Jesus looked like. The most typical North American representation is a tall, lean, Caucasian man with long, flowing, light brown hair. -

The Life of Mary Cycle at the Chora Church and Historical Pre- Occupations with the Chastity of the Virgin Mary in Byzantium

1 Purity as a Pre-requisite for Praise: The Life of Mary Cycle at the Chora Church and Historical Pre- Occupations with the Chastity of the Virgin Mary in Byzantium Elizabeth Fortune AH 4119 Natif 12-6-2013 2 In this paper I will explore historical preoccupations with the physical purity of the Virgin Mary within Christian Byzantium. My discussion will focus on the second-century apocryphal gospel the Protoevangelium of James, Cappadocian theology, and the role of women within Byzantine society. I will ground my exploration within the context of historical debates regarding the status of the Virgin in the Early Christian Church. I will particularly discuss Mary’s significance as the Theotokos (God-bearer)within Byzantium, as it was necessarily informed and justified by perpetual assertions regarding the purity and sanctity of Mary’s physical body. I will utilize the decorative program of the Chora Church in Istanbul as a visual manifestation of perpetual concerns with Mary’s purity within Christian Byzantium. As the resident monastic order at the Chora, Cappadocian devotion to the Virgin necessarily influenced the iconographic and thematic content of the church’s decorative program.1 The particular nature of Cappadocian Marian devotion is thus relevant to my discussion of the Life of Mary Cycle, the Protoevangelium, and the Virgin’s role as Theotokos within Byzantium and the Eastern Church. In order to contextualize the Life of Mary cycle at the Chora, I will briefly investigate other historical and contemporary visual examples of the subject. I will then discuss one mosaic scene from the Life of Mary cycle at Chora: the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple (fig. -

The Kariye Camii: an Introduction ROBERT G. OUSTERHOUT History ORIGINALLY the MAIN CHURCH of the Chora Monastery, the Building N

The Kariye Camii: An Introduction ROBERT G. OUSTERHOUT History ORIGINALLY THE MAIN CHURCH of the Chora monastery, the building now known as the Kariye Museum, or traditionally as the Kariye Camii (Mosque), represents one of the oldest and most important religious foundations of Byzantine Constantinople. Second in renown only to Justinian's Great Church, the Kariye is an increasingly popular tourist destination, known primarily for its splendid mosaic and fresco decoration. The early history and traditions associated with the Chora monastery have long been known from Byzantine texts, but the archaeological investigations and the careful examination of the fabric of the building carried out by the Byzantine Institute of America in the 1950s clarified many aspects of the building's long and complex development. The site of the Chora lay outside the fourth-century city of Constantine but was enclosed by the Land Walls built by Theodosius II (r. 408-450) in the early fifth century, located near the Adrianople Gate (Edirne Kepi). The rural character of the site, which seems to have remained sparsely inhabited well into the twentieth century, may account for the name chora, which can be translated as "land," "country" or "in the country." The appellation chora also has other meanings, and in later Byzantine times the name was reinterpreted in a mystical sense as "dwelling place" or "container": in the decoration of the building Christ is identified as chora ton zoonton (land, or dwelling place of the living and the Virgin as chora ton achoretou (container of the uncontainable). Both are wordplays on the name of the monastery: the former derived from Psalm 116, a verse used in the funerary liturgy, and the latter from the Akathistos Hymn honoring the Virgin. -

The Gates of Hell Shall Not Prevail the Universe and Our Lives Ultimately Are Bounded by God’S Unfathomable Love and Righteousness

The Gates of Hell Shall Not Prevail The universe and our lives ultimately are bounded by God’s unfathomable love and righteousness. How can we unravel the apparent incongruity between God’s loving character and the existence of hell? Christian Reflection Prayer† A Series in Faith and Ethics For neither death nor life, nor angels, nor princes, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to sepa- rate us from the love of God in Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen. Scripture Reading: 1 Peter 3:13—4:6 Focus Article: Reflection The Gates of Hell Shall One of the church’s most ancient claims is that God’s love, Not Prevail expressed in the death of Jesus Christ, conquers hell itself. The (Heaven and Hell, pp. 31- Apostles’ Creed proclaims that Christ was not only “crucified, 34) dead, and buried,” but also that he “descended into hell.” This means, says Rufinus (ca. 400 A.D.), that Christ brought “three Suggested Article: kingdoms at once into subjection under his sway.” All creatures My Maker Was the “in heaven and on earth and under the earth” bend the knee to Primal Love Jesus, as Paul teaches in Philippians 2:10. (Heaven and Hell, pp. 35- Related to this is the Harrowing of Hell, the teaching that 38) Christ drew out of hell the Old Testament saints who lived by faith in anticipation of the coming of Christ. In this way the church explained how God’s love extends “to all those who would seem to be damned by no other fault than having been born before Christ,” Ralph Wood observes. -

Finding the Traces of Jesus Douglas L

Finding the Traces of Jesus Douglas L. Griffin n a previous article (The Fourth R 33-1, Jan-Feb 2020) Refrain: I argued that reading the Bible as theological fiction Tell me the story of Jesus, frees one from the necessity of clarifying whether or Write on my heart every word. I Tell me the story most precious, not biblical references are factual and invites one to enter into the diverse worlds of meaning disclosed in the Bible’s Sweetest that ever was heard. figurative references. In the process the reader is in a posi- Fasting alone in the desert, tion to recognize that the Bible’s supernatural references Tell of the days that are past. are imaginative ones that articulate inexplicable phenom- How for our sins He was tempted, ena through the culturally mediated interpretations, be- Yet was triumphant at last. liefs, rituals, symbols, and traditions underlying the Bible’s Tell of the years of His labor, origins. Indeed, once we have clarified that the supernatu- Tell of the sorrow He bore. He was despised and afflicted, ral references are imaginative and the narratives make figu- Homeless, rejected and poor. rative, not literal, sense the stories receive a new voice with which to speak. Readers are now in a position to let the Refrain texts confront them in ways they could not before. They Tell of the cross where they nailed Him, are not distracted by arguments about what did and did Writhing in anguish and pain. not “really” happen. Instead, they can discern horizons of Tell of the grave where they laid Him, meaning in the stories that will help them make sense of Tell how He liveth again. -

WHG Asian History Lesson: Exploring the Changing Names of Cities

WHG Asian History Lesson: Exploring the Changing Names of Cities Part 1: Introduction of Concept of Place Changing Place Names Start by showing the lyrics video to the song “Istanbul not Constantinople” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ALkjA1t8ibQ). Question for class: What two cities with changed names are named in the song? Answers: Constantinople became Istanbul, New Amsterdam became New York Question for class: The song hints as to why the name was changed in one case. Did you catch it? Answer: “That’s nobody’s business but the Turks.” Question for class: What does that mean? Answer: The place known as Istanbul has had a number of names over time. The city was founded in 657 B.C.E. and was called Byzantium. It later became a part of the Roman Empire and the Emperor Constantine decided to make it his new capital, the second Rome. In 330 CE the place started to be called Constantinople. In 1453 Ottoman forces, led by Mehmed II, took over Constantinople and it became the capital of the Ottoman Empire. The Otoman Empire collapsed after World War I, partially due to the Ottoman Empire being on the losing side of the war. During the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Greeks and Turkish fought a war of independence. Turkey officially gained its independence in 1923 and the capital was moved to Ankara. In 1930, Turkish officials renamed Constantinople Istanbul, which was a name by which it had been informally known for a long time. Question: Do you understand the pattern for New Amsterdam? Answer: The British changed the name to New York after taking it over from the Dutch.