A Digital Logic Based Experimental Design of a Dsp/Communication System for Ecet Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Signals

Technical Information Digital Signals 1 1 bit t Part 1 Fundamentals Technical Information Part 1: Fundamentals Part 2: Self-operated Regulators Part 3: Control Valves Part 4: Communication Part 5: Building Automation Part 6: Process Automation Should you have any further questions or suggestions, please do not hesitate to contact us: SAMSON AG Phone (+49 69) 4 00 94 67 V74 / Schulung Telefax (+49 69) 4 00 97 16 Weismüllerstraße 3 E-Mail: [email protected] D-60314 Frankfurt Internet: http://www.samson.de Part 1 ⋅ L150EN Digital Signals Range of values and discretization . 5 Bits and bytes in hexadecimal notation. 7 Digital encoding of information. 8 Advantages of digital signal processing . 10 High interference immunity. 10 Short-time and permanent storage . 11 Flexible processing . 11 Various transmission options . 11 Transmission of digital signals . 12 Bit-parallel transmission. 12 Bit-serial transmission . 12 Appendix A1: Additional Literature. 14 99/12 ⋅ SAMSON AG CONTENTS 3 Fundamentals ⋅ Digital Signals V74/ DKE ⋅ SAMSON AG 4 Part 1 ⋅ L150EN Digital Signals In electronic signal and information processing and transmission, digital technology is increasingly being used because, in various applications, digi- tal signal transmission has many advantages over analog signal transmis- sion. Numerous and very successful applications of digital technology include the continuously growing number of PCs, the communication net- work ISDN as well as the increasing use of digital control stations (Direct Di- gital Control: DDC). Unlike analog technology which uses continuous signals, digital technology continuous or encodes the information into discrete signal states (Fig. 1). When only two discrete signals states are assigned per digital signal, these signals are termed binary si- gnals. -

Chapter 1 Computers and Digital Basics Computer Concepts 2014 1 Your Assignment…

Chapter 1 Computers and Digital Basics Computer Concepts 2014 1 Your assignment… Prepare an answer for your assigned question. Use Chapter 1 in the book and this PowerPoint to procure information. Prepare a PowerPoint presentation to: 1. Show your answer and additional information/facts – make sure you understand and can explain your answer. Provide as must information and detail as possible. Add graphics to enhance. 2. Where in the book did you find your information? Include the page number. 3. What more do you need to find out to help you better understand this question? Be prepared to share your information with the class. Chapter 1: Computers and Digital Basics 2 1 The Digital Revolution The digital revolution is an ongoing process of social, political, and economic change brought about by digital technology, such as computers and the Internet The technology driving the digital revolution is based on digital electronics and the idea that electrical signals can represent data, such as numbers, words, pictures, and music Chapter 1: Computers and Digital Basics 6 1 The Digital Revolution Digitization is the process of converting text, numbers, sound, photos, and video into data that can be processed by digital devices The digital revolution has evolved through four phases, beginning with big, expensive, standalone computers, and progressing to today’s digital world in which small, inexpensive digital devices are everywhere Chapter 1: Computers and Digital Basics 7 1 The Digital Revolution Chapter 1: Computers and Digital Basics -

Lecture Notes for Digital Electronics

Lecture Notes for Digital Electronics Raymond E. Frey Physics Department University of Oregon Eugene, OR 97403, USA [email protected] March, 2000 1 Basic Digital Concepts By converting continuous analog signals into a finite number of discrete states, a process called digitization, then to the extent that the states are sufficiently well separated so that noise does create errors, the resulting digital signals allow the following (slightly idealized): • storage over arbitrary periods of time • flawless retrieval and reproduction of the stored information • flawless transmission of the information Some information is intrinsically digital, so it is natural to process and manipulate it using purely digital techniques. Examples are numbers and words. The drawback to digitization is that a single analog signal (e.g. a voltage which is a function of time, like a stereo signal) needs many discrete states, or bits, in order to give a satisfactory reproduction. For example, it requires a minimum of 10 bits to determine a voltage at any given time to an accuracy of ≈ 0:1%. For transmission, one now requires 10 lines instead of the one original analog line. The explosion in digital techniques and technology has been made possible by the incred- ible increase in the density of digital circuitry, its robust performance, its relatively low cost, and its speed. The requirement of using many bits in reproduction is no longer an issue: The more the better. This circuitry is based upon the transistor, which can be operated as a switch with two states. Hence, the digital information is intrinsically binary. So in practice, the terms digital and binary are used interchangeably. -

Lecture 9 Analog and Digital I/Q Modulation

Lecture 9 Analog and Digital I/Q Modulation Analog I/Q Modulation • Time Domain View •Polar View • Frequency Domain View Digital I/Q Modulation • Phase Shift Keying • Constellations 11/4/2006 Coherent Detection Transmitter Output 0 x(t) y(t) π 2cos(2 fot) Receiver Output Lowpass y(t) z(t) r(t) π 2cos(2 fot) • Requires receiver local oscillator to be accurately aligned in phase and frequency to carrier sine wave 11/4/2006 L Lecture 9 Fall 2006 2 Impact of Phase Misalignment in Receiver Local Oscillator Transmitter Output 0 x(t) y(t) π 2cos(2 fot) Receiver Output Output is zero Lowpass y(t) z(t) r(t) π 2sin(2 fot) • Worst case is when receiver LO and carrier frequency are phase shifted 90 degrees with respect to each other 11/4/2006 L Lecture 9 Fall 2006 3 Analog I/Q Modulation Baseband Input iti(t)(t) it (t) t cos 2 f tπ yt (t) 2cos(2( π 0 )f1t) π 2sin(2sin() 2π f0t f1t) qqt(t)(t) t qt (t) • Analog signals take on a continuous range of values (as viewed in the time domain) • I/Q signals are orthogonal and therefore can be transmitted simultaneously and fully recovered 11/4/2006 L Lecture 9 Fall 2006 4 Polar View of Analog I/Q Modulation it (t) = i(t)cos() 2π fot + 0° ii(t(t)t) it (t) qt (t) = q(t)cos() 2π fot + 90° = q(t)sin() 2π fot t cos 2π f tπ y (t) 2cos(2( 0 )f1t) t 2 2 π 2sin(2sin() 2π f0t f1t) yt (t) = i (t) + q (t) cos() 2π fot + θ(t) qq(tt(t)) −1 where θ(t) = tan q(t)/i(t) t qt (t) −180°<θ < 180° 11/4/2006 L Lecture 9 Fall 2006 5 Polar View of Analog I/Q Modulation (Con’t) • Polar View shows amplitude and phase of it(t), qt(t) and yt(t) combined signal for transmission at a given frequency f. -

Introduction (Pdf)

chapter1.fm Page 1 Thursday, August 17, 2000 4:43 PM CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION The evolution of digital circuit design n Compelling issues in digital circuit design n How to measure the quality of digital design n Valuable references 1.1 A Historical Perspective 1.2 Issues in Digital Integrated Circuit Design 1.3 Quality Metrics of A Digital Design 1.4 Summary 1.5 To Probe Further 1 chapter1.fm Page 2 Thursday, August 17, 2000 4:43 PM 2 INTRODUCTION Chapter 1 1.1A Historical Perspective The concept of digital data manipulation has made a dramatic impact on our society. One has long grown accustomed to the idea of digital computers. Evolving steadily from main- frame and minicomputers, personal and laptop computers have proliferated into daily life. More significant, however, is a continuous trend towards digital solutions in all other areas of electronics. Instrumentation was one of the first noncomputing domains where the potential benefits of digital data manipulation over analog processing were recognized. Other areas such as control were soon to follow. Only recently have we witnessed the con- version of telecommunications and consumer electronics towards the digital format. Increasingly, telephone data is transmitted and processed digitally over both wired and wireless networks. The compact disk has revolutionized the audio world, and digital video is following in its footsteps. The idea of implementing computational engines using an encoded data format is by no means an idea of our times. In the early nineteenth century, Babbage envisioned large- scale mechanical computing devices, called Difference Engines [Swade93]. Although these engines use the decimal number system rather than the binary representation now common in modern electronics, the underlying concepts are very similar. -

A Micro-Programmable Correlator for Real-Time Radar Processing

ALKER: Correlator for radar processing A MICRO-PROGRAMMABLE CORRELATOR FOR REAL-TIME RADAR PROCESSING by Hans-J¢rgen Alker ELECTRONICS RESEARCH LABORATORY (ELAB) Trondheim, NORWAY ABSTRACT This paper presents a novel design of a mul tibi t ·, digital correlator for incoherent scatter radar observations. By utilizing bit-slice microprocessor elements and internal control by microcode instructions, a high-speed arithmetical preprocessor has been developed. Arithmetical and control operations are separated to obtain increased speed performance. The arithmetical part is optimized for complex auto/cross correlation processing and has an effective rate of 24·106 multiplications/sec. Input data has 8-bit accuracy in integer format. The processor includes, at input, a 2-ported buffer memory for storing single/multiple channel inputs. Processing results are temporarily stored in a 4 K word high-speed memory before transferred to a general-purpose computer. Processing speed can be increased by adding up to 3 slave processors thus achieving direct parallel processing. Internal hardware is available for interface with standard CAMAC modules. INTRODUCTION During 1976-79 a feasibility study of a digital, multibit correlator for the EISCAT (European Incoherent SCATter) radar system was conducted. The main topics of the study embraced system design and hardware construction of a digital processor which fulfilled the specifications for real-time data process- ing. The result of the study is a prototype construction of a high- speed multiprocessor system under interactive control of the EISCAT radar site computer. Support software for microprogram development, simulation and hardware testing are available for execution on a host computer. The main objectives for constructing a digital processor for the EISCAT system were the ultimate requirements for special purpose data handling algorithms and the real-time processing speed. -

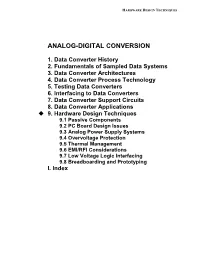

Hardware Design Techniques

HARDWARE DESIGN TECHNIQUES ANALOG-DIGITAL CONVERSION 1. Data Converter History 2. Fundamentals of Sampled Data Systems 3. Data Converter Architectures 4. Data Converter Process Technology 5. Testing Data Converters 6. Interfacing to Data Converters 7. Data Converter Support Circuits 8. Data Converter Applications 9. Hardware Design Techniques 9.1 Passive Components 9.2 PC Board Design Issues 9.3 Analog Power Supply Systems 9.4 Overvoltage Protection 9.5 Thermal Management 9.6 EMI/RFI Considerations 9.7 Low Voltage Logic Interfacing 9.8 Breadboarding and Prototyping I. Index ANALOG-DIGITAL CONVERSION HARDWARE DESIGN TECHNIQUES 9.1 PASSIVE COMPONENTS CHAPTER 9 HARDWARE DESIGN TECHNIQUES This chapter, one of the longer of those within the book, deals with topics just as important as all of those basic circuits immediately surrounding the data converter, discussed earlier. The chapter deals with various and sundry circuit/system issues which fall under the guise of system hardware design techniques. In this context, the design techniques may be all those support items surrounding a data converter, excluding the data converter itself. This includes issues of passive components, printed circuit design, power supply systems, protection of linear devices against overvoltage and thermal effects, EMI/RFI issues, high speed logic considerations, and finally, simulation, breadboarding and prototyping. Some of these topics aren't directly involved in the actual signal path of a design, but they are every bit as important as choosing the correct device and surrounding circuit values. Remote sensing and signal conditioning is such a vital part of data conversion that a considerable amount of discussion is given to topics such as overvoltage protection, cable driving, shielding, and receiving—where the remote interface is often with op amps and instrumentation amplifiers. -

MAS.632 Conversational Computer Systems

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu MAS.632 Conversational Computer Systems Fall 2008 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. 10 Basics of Telephones This and the following chapters explain the technology and computer applica tions oftelephones, much as earlier pairs ofchapters explored speech coding, syn thesis, and recognition. The juxtaposition of telephony with voice processing in a single volume is unusual; what is their relationship? First, the telephone is an ideal means to access interactive voice response services such as those described in Chapter 6. Second, computer-based voice mail will give a strong boost to other uses of stored voice such as those already described in Chapter 4 and to be explored again in Chapter 12. Finally, focusing on communication,i.e., the task rather than the technology, leads to a better appreciation of the broad intersec tion of speech, computers, and our everyday work lives. This chapter describes the basic telephone operations that transport voice across a network to a remote location. Telephony is changing rapidly in ways that radically modify how we think about and use telephones now and in the future. Conventional telephones are already ubiquitous for the business traveler in industrialized countries, but the rise in personal, portable, wireless telephones is spawning entirely new ways of thinking about universal voice connectivity. The pervasiveness of telephone and computer technologies combined with the critical need to communicate in our professional lives suggest that it would be foolish to ignore the role of the telephone as a speech processing peripheral just like a speaker or microphone. -

Carriers and Modulation DIGITAL TRANSMISSION of DIGITAL DATA

DIGITAL TRANSMISSION OF Carriers and Modulation DIGITAL DATA CS442 Review… Baseband Transmission Digital transmission is the transmission of electrical Baseband Transmission pulses. Digital information is binary in nature in that it has only two possible states 1 or 0. With unipolar signaling techniques, the voltage is Sequences of bits encode data (e.g., text always positive or negative (like a dc current). characters). In bipolar signaling, the 1’s and 0’s vary from a plus Digital signals are commonly referred to as baseband signals. voltage to a minus voltage (like an ac current). In order to successfully send and receive a message, both the sender and receiver have to agree how In general, bipolar signaling experiences fewer errors often the sender can transmit data (data rate). than unipolar signaling because the signals are Data rate often called bandwidth – but there is a more distinct. different definition of bandwidth referring to the frequency range of a signal! 1 Baseband Transmission Baseband Transmission Manchester encoding is a special type of unipolar signaling in which the signal is changed from a high to low (0) or low to high (1) in the middle of the signal. • More reliable detection of transition rather than level – consider perhaps some constant amount of dc noise, transitions still detectable but dc component could throw off NRZ-L scheme – Transitions still detectable even if polarity reversed Manchester encoding is commonly used in local area networks (ethernet, token ring). ANALOG TRANSMISSION OF Manchester Encoding DIGITAL DATA Analog Transmission occurs when the signal sent over the transmission media continuously varies from one state to another in a wave-like pattern. -

United States Patent (19) 11) Patent Number: 4,499,535 Bachman Et Al

United States Patent (19) 11) Patent Number: 4,499,535 Bachman et al. (45) Date of Patent: Feb. 12, 1985 54) DIGITAL COMPUTER SYSTEM HAVING 3,821,711 6/974 Elam et al. .................. 340/347 DD DESCRIPTORS FORWARIABLE LENGTH 3,840,862 10/1974 Ready ................................. 364/200 ADDRESSING FOR A PLURALITY OF 4,050,058 9/1977 Garlic .......... ... 364/200 4,077,059 2/1978 Cordi et al. ......................... 364/200 INSTRUCT ON DIALECTS 4,084.226 4/978 Anderson et al. .................. 364/200 75 Inventors: Brett L. Bachman, Boston, Mass.; 4,136,386 1/1979 Annunziata et al. ............... 364/200 Richard A. Belgard, Saratoga, Calif.; 4,179,738 12/1979 Fairchild et al. ... ... 364/200 4,206,503 6/1980 Woods et al. ... ... 364/200 David H. Bernstein, Ashland; 4,210,960 7/1980 Borgerson ........................... 364/200 Richard G. Bratt, Wayland, both of 4,241,397 12/1980 Strecker et al. .................... 364/200 Mass.; Gerald F. Clancy, Saratoga, 4,241,399 12/1980 Strecker et al. .................... 364/200 Calif.; Edward S. Gavrin, Lincoln, Mass.; Ronald H. Gruner, Cary, OTHER PUBLICATIONS N.C.; Thomas M. Jones, Chapel Hill, N.C.: Craig J. Mundie; James T. Bit Sliced Microprocessor Architecture-Alexan Nealon, both of Cary, N.C.; John F. drides; IEEE Computer-Jun. 1978, pp. 56-81-L7904 Pilat, Raleigh, N.C.; Stephen I. 0001. Schleimer, Chapel Hill, N.C.; Steven Primary Examiner-Harvey E. Springborn J. Wallach, Saratoga, Calif. Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Joel Wall; Gene Nelson; Leonard Suchyta (73) Assignee: Data General Corporation, Westboro, Mass. (57) ABSTRACT (21) Appl. No.: 266,427 A digital computer uses a memory which is structured into objects, which are blocks of storage of arbitrary 22) Fled: May 22, 1981 length, in which data items are accessed by descriptors (51) Int. -

Digital Audio Standards

Digital Audio Standards MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE DIGITAL would consider the possibility of using the 45-kHz fre- AUDIO STANDARDS COMMITTEE quency proposed by Heaslett. 1.5 Mr. Willcocks gave the available technical details of Date: 1977 December 1 und 2 some 14 presently-used digital audio systems. He sub- Time: 1830 hours sequently prepared a report containing this information for Place: Snowbird Resort, Salt Lake City, Utah distribution to the committee (see page 56). 1.6 Several members expressed the urgency for sampling Present: Chairman, John G. McKnight (Magnetic Refer- frequency standardization because of the number of digital ence Laboratory); members, Stanley Becker (Scully/ audio recording systems- both studio and consumer Dictaphone); Gregory Boganz (RCA Records); Vic Goh types- now nearing completion and commercial availa- (Victor Company of Japan (JVC)); Thomas Hay (MCI, bility. Inc .); Alastair Heaslett (Ampex Corporation); M. Carlos Kennedy (Ampex Corporation); William Kinghom (Telex 1.7 The committee was unable to find an acceptable single Communications); K. Kimihira (Akai America); Masahiro frequency, given the conflicting requirements of the pres- Kosaka (Wireless Research Lab, Matsushita Elect. Inc. ent TV-compatible proposal, the 3M studio recorder, and Co.); Alfred H. Moris (3M Company); Thomas G. Stoc- the Japanese consumer recorders. The committee asked kham, Jr. (Soundstream, Inc.); Martin Willcocks Messrs. Heaslett, Youngquist and Kosaka each to prepare (Willcocks Research Consultants); James V. White (CBS a report giving details explaining why they chose the Technology Center); Yoshito Yamagudi (Melco Sales Inc. frequency they did, and what penalties the other frequen- Mitsubishi Electric Corp.); Robert J. Youngquist (3M cies discussed would entail. -

Digital Audio Systems

Digital Audio Systems While analog audio produces a constantly varying voltage or current, digital audio produces a non-continuous list of numbers. The maximum size of the numbers will determine the dynamic range of the system, since the smallest signal possible will result from the lowest order bit (LSB or least significant bit) changing from 0 to 1. The D/A converter will decode this change as a small voltage shift, which will be the smallest change the system can produce. The difference between this voltage and the voltage encoded by the largest number possible (all bits 1’s) will become the dynamic range. This leads to one of the major differences between analog and digital audio: as the signal level increases, an analog system tends to produce more distortion as overload is approached. A digital system will introduce no distortion until its dynamic range is exceeded, at which point it produces prodigious distortion. As the signal becomes smaller, an analog system produces less distortion until the noise floor begins to mask the signal, at which point the signal-to-noise ratio is low, but harmonic distortion of the signal does not increase. With low amplitude signals, a digital system produces increasing distortion because there are insufficient bits available to accurately measure the small signal changes. There is a difference in the type of interference at low signal levels between analog and digital audio systems. Analog systems suffer from thermal noise generated by electronic circuitry. This noise is white noise: that is, it has equal power at every frequency. It is the “hiss” like a constant ocean roar with which we are so familiar.