Project Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

RAMP -2: Procurement Plan – Jan. 2017. (RURAL ROADS AND MOBILTY PROJECT-2 PP:2017) Public Disclosure Authorized I. General 1. Project Information: Country: Nigeria Borrower: Federal Government of Nigeria Project Name: Rural Road and Mobility Project 2 (RAMP2). Loan/Credit No.: P095003 PIA: Federal Project Management Unit (FPMU) 2. Bank’s approval Date of the procurement Plan [Original: December 2007]: Revision of Updated Procurement Plan, June 2010]. Updated January 2017 2. Date of General Procurement Notice: Dec 24, 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized 3. Period covered by initial procurement plans: The procurement period of project covered from year June 2010 to December 2012; (Period covered by this current procurement plan: and January 2017 to December 2017 and or to June 2018). II. Goods and Works and non-consulting services. 1. Prior Review Threshold: Procurement Decisions subject to Prior Review by the Bank as stated in Appendix 1 to the Guidelines for Procurement: Public Disclosure Authorized Procurement Method Prior Review Threshold Comment (US$ equivalent) 1. ICB and LIB (Goods and services other > 1,000,000.00 ALL than consultancy services) 2. NCB (Goods) 100,000.00 ≤ 1,000,000.00 NONE 3 IT System, and Non-Consulting Services > 1,000,000.00 (ICB). NCB: 100,000.00 ≤ 1,000,000.00 4. ICB (Works) > 10,000,000.00 ALL 5. NCB (Works) 300,000 ≤ 10,000,000.00 NONE 6 Shopping-Goods < 100,000.00 NONE 7 Shopping-Works < 300,000.00 NONE 8. Community Participation in All Values SSS of Community Procurement acceptable to the Maintenance Association and described in the PIM Public Disclosure Authorized groups, etc. -

The Hermeneutics of Women Disciples in Mark's Gospel: an Igbo Contextual Reconstruction

The Hermeneutics of Women Disciples in Mark's Gospel: An Igbo Contextual Reconstruction Author: Fabian Ekwunife Ezenwa Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:108068 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2018 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. THE HERMENEUTICS OF WOMEN DISCIPLES IN MARK’S GOSPEL: AN IGBO CONTEXTUAL RECONSTRUCTION A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE LICENTIATE IN SACRED THEOLOGY (S.T.L) DEGREE FROM THE BOSTON COLLEGE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AND MINISTRY BY EZENWA FABIAN EKWUNIFE, C.S.SP MENTOR: DR ANGELA KIM HARKINS CO-MENTOR: PROF. MARGARET E. GUIDER, OSF MAY 3, 2018 BOSTON COLLEGE | Ezenwa, C.S.Sp DEDICATION TO MY MOTHER, MARCELINA EZENWA (AKWUGO UMUAGBALA) AND ALL UMUADA IGBO i | Ezenwa, C.S.Sp TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………….1 CHAPTER ONE: SCHOLARSHIP REVIEW ………………………………………….…..9 1.1. QUESTION ABOUT MARK’S PORTRAIT OF WOMEN ………………………….…..10 1.2. QUESTION ABOUT THE APPROACH AND PARADIGM OF INVESTIGATION ......18 1.3. CHALLENGING THE CONCEPT, “ἩO MATHĒTAI” (“THE DISCIPLES”) ……..…..24 CONCLUSION ………………………………………………………………………………...30 CHAPTER TWO: IGBO CULTURAL STUDY IN CONTEXT …………………….....…32 2.1. DEVELOPMENT OF BIBLICAL CRITICISM ……………………………………......…33 2.2. IGBO COMMUNITY CONSCIOUSNESS, THE “NWANNE” PHILOSOPHY OF LIFE.35 2.3. THE IGBO PEOPLE OF NIGERIA ………………………………………………………39 2.3.1. WHO ARE THE IGBO? …………………………………………………………….….39 2.3.2. SOCIO-POLITICAL LIFE OF THE IGBO ……………………………………….…....40 2.3.3. IGBO WORLDVIEW ……………………………………………………………….….42 2.3.4. IGBO PATRIARCHY ………………………………………………………………….44 2.3.5. ROLES PLAYED BY INDIVIDUALS IN IGBO SOCIETY ……………………….....47 2.3.6. -

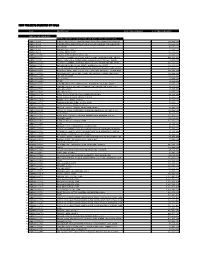

Directory of Polling Units Abia State

FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) ABIA STATE DIRECTORY OF POLLING UNITS Revised January 2015 DISCLAIMER The contents of this Directory should not be referred to as a legal or administrative document for the purpose of administrative boundary or political claims. Any error of omission or inclusion found should be brought to the attention of the Independent National Electoral Commission. INEC Nigeria Directory of Polling Units Revised January 2015 Page i Table of Contents Pages Disclaimer................................................................................. i Table of Contents ………………………………………………… ii Foreword.................................................................................. iv Acknowledgement.................................................................... v Summary of Polling Units......................................................... 1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREAS Aba North ………………………………………………….. 2-15 Aba South …………………………………………………. 16-28 Arochukwu ………………………………………………… 29-36 Bende ……………………………………………………… 37-45 Ikwuano ……………………………………………………. 46-50 Isiala Ngwa North ………………………………………… 51-56 Isiala Ngwa South ………………………………………… 57-63 Isuikwuato …………………………………………………. 64-69 Obingwa …………………………………………………… 70-79 Ohafia ……………………………………………………… 80-91 Osisioma Ngwa …………………………………………… 92-95 Ugwunagbo ……………………………………………….. 96-101 Ukwa East …………………………………………………. 102-105 Ukwa West ………………………………………..………. 106-110 Umuahia North …………………………………..……….. 111-118 Umuahia South …………………………………..……….. 119-124 Umu-Nneochi -

The Abolition of the Slave Trade in Southeastern Nigeria, 1885–1950

THE ABOLITION OF THE SLAVE TRADE IN SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1885–1950 Toyin Falola, Senior Editor The Frances Higginbotham Nalle Centennial Professor in History University of Texas at Austin (ISSN: 1092–5228) A complete list of titles in the Rochester Studies in African History and the Diaspora, in order of publication, may be found at the end of this book. THE ABOLITION OF THE SLAVE TRADE IN SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1885–1950 A. E. Afigbo UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER PRESS Copyright © 2006 A. E. Afigbo All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded, or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First published 2006 University of Rochester Press 668 Mt. Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620, USA www.urpress.com and Boydell & Brewer Limited PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK www.boydellandbrewer.com ISBN: 1–58046–242–1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Afigbo, A. E. (Adiele Eberechukwu) The abolition of the slave trade in southeastern Nigeria, 1885-1950 / A.E. Afigbo. p. cm. – (Rochester studies in African history and the diaspora, ISSN 1092-5228 ; v. 25) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58046-242-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Slavery–Nigeria–History. 2. Slave trade–Nigeria–History. 3. Great Britain–Colonies–Africa–Administration I. Title. HT1394.N6A45 2006 306.3Ј6209669–dc22 2006023536 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. This publication is printed on acid-free paper. -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

South East Capital Budget Pull

2014 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET Of the States in the South East Geo-Political Zone By Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) 2014 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET Of the States in the South East Geo-Political Zone Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) ii 2014 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET Of the States in the South East Geo-Political Zone Compiled by Centre for Social Justice For Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) iii First Published in October 2014 By Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) C/o Centre for Social Justice 17 Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja. Website: www.csj-ng.org ; E-mail: [email protected] ; Facebook: CSJNigeria; Twitter:@censoj; YouTube: www.youtube.com/user/CSJNigeria. iv Table of Contents Acknowledgement v Foreword vi Abia 1 Imo 17 Anambra 30 Enugu 45 Ebonyi 30 v Acknowledgement Citizens Wealth Platform acknowledges the financial and secretariat support of Centre for Social Justice towards the publication of this Capital Budget Pull-Out vi PREFACE This is the third year of compiling Capital Budget Pull-Outs for the six geo-political zones by Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP). The idea is to provide information to all classes of Nigerians about capital projects in the federal budget which have been appropriated for their zone, state, local government and community. There have been several complaints by citizens about the large bulk of government budgets which makes them unattractive and not reader friendly. -

Modelling of Maximum Annual Flood for Regional Watersheds Using Markov Model Benjamin Nnamdi Ekwueme1, Andy Obinna Ibeje2*, Anthony Ekeleme3

Saudi Journal of Civil Engineering Abbreviated Key Title: Saudi J Civ Eng ISSN 2523-2657 (Print) |ISSN 2523-2231 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: https://saudijournals.com Original Research Article Modelling of Maximum Annual Flood for Regional Watersheds Using Markov Model Benjamin Nnamdi Ekwueme1, Andy Obinna Ibeje2*, Anthony Ekeleme3 1Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Nigeria Nsukka Enugu State, Nigeria 2Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Imo State University, Owerri, Nigeria 3Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Abia State University, Uturu, Nigeria DOI: 10.36348/sjce.2021.v05i02.002 | Received: 07.02.2021 | Accepted: 22.02.2021 | Published: 08.03.2021 *Corresponding author: Andy Obinna Ibeje Abstract A study was undertaken to develop and apply the first-order Markov model in generating the synthetic stream flow for Adada, Ivo, Otamiri, Imo and Ajali rivers located in South East Nigeria. The best-fit probability distributions for the maximum annual stream flows were lognormal, Weibull, normal and lognormal for Adada, Ajali, Ivo, Otamiri and Imo (Umuokpara) rivers respectively were used in simulating the associated random deviates. The stream flow data for 10 years (1980 to 1989) were used to develop the model and to predict the stream flow. The model performance was evaluated with the aid of the coefficient of determination (R2). The results indicated a satisfactory performance as evidenced by R2 values of 51.69%, 31.3%, 21.4%, 33% and 21% for Adada, Ajali, Ivo, Otamiri and Imo rivers respectively. The developed models were used to generate 50-year synthetic stream flows of these rivers. -

Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC)

FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) IMO STATE DIRECTORY OF POLLING UNITS Revised January 2015 DISCLAIMER The contents of this Directory should not be referred to as a legal or administrative document for the purpose of administrative boundary or political claims. Any error of omission or inclusion found should be brought to the attention of the Independent National Electoral Commission. INEC Nigeria Directory of Polling Units Revised January 2015 Page i Table of Contents Pages Disclaimer............................................................................... i Table of Contents ………………………………………………. ii Foreword................................................................................. iv Acknowledgement................................................................... v Summary of Polling Units........................................................ 1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREAS Aboh-Mbaise ……………………………………………… 2-7 Ahiazu-Mbaise ……………………………………………. 8-13 Ehime-Mbano …………………………………………….. 14-20 Ezinihitte Mbaise …………………………………………. 21-27 Ideato North ………………………………………………. 28-36 Ideato South ……………………………………………… 37-42 Ihitte/Uboma (Isinweke) …………………………………. 43-48 Ikeduru …………………………………………………….. 49-55 Isiala Mbano (Umuelemai) ………………………………. 56-62 Isu (Umundugba) …………………………………………. 63-68 Mbaitoli (Nwaorieubi) …………………………………….. 69-78 Ngor-Okpala (Umuneke) ………………………………… 79-85 Njaba (Nnenasa) …………………………………………. 86-92 Nkwerre ……………………………………………………. 93-98 Nwangele (Onu/Nwangele Amaigbo) ………………….. 99-103 Obowo (Otoko) -

The Osu Caste System in Isuochi, Abia State, Nigeria, 1956-2012

i UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES TITLE: THE OSU CASTE SYSTEM IN ISUOCHI, ABIA STATE, NIGERIA, 1956-2012 A PROJECT TOPIC SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS (M.A) DEGREE IN HISTORY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES. BY KAORUKWE UCHENNA PG/MA/15/77199 SUPERVISOR DR. NNAMDI C. AJAEBILI AUGUST, 2018 i TITLE PAGE THE OSU CASTE SYSTEM IN ISUOCHI, ABIA STATE, NIGERIA, 1956- 2012 ii CERTIFICATION This is to certify that this research work has been examined and approved for the award of Degree of Master of Arts in History and International Studies ---------------------------------------- ----------------------- DR. NNAMDI C. AJAEBILI DATE ( SUPERVISOR) ----------------------------------------- ----------------------- PROF. A.N. AKWANYA DATE HEAD OF DEPARTMENT --------------------------------------- ----------------------- PROF. WINIFRED AKODA DATE EXTERNAL EXAMINER iii DEDICATION To my mother, Margreth Kaorukwe. She did her best in bringing me up morally. iv ACKNOWLEGEMENTS I deem it fit to express my heartfelt gratitude to all those who had made it possible for this research work to come to limelight. My utmost thanks go to Almighty God who gave me the strength to actualize this work. I remain grateful to my mentor, Dr. P.U Iwunna, for his invaluable contributions. I will not forget my mother and my elder brother, Mrs. Margreth Nkemawunvu Kaorukwe and Chief Monday Kaorukwe (Okachimee 1 of Amuda Isuochi), for their support and encouragement. In a very special way, I remain grateful to my supervisor Dr.Nnamdi C. Ajaebili, whose fatherly and scholarly guidance, corrections, and suggestions contributed to the actualization of this work. I remain eternally grateful to Professor A.N. -

THE AESTHETICS of IGBO MASK THEATRE by VICTOR

THE COMPOSITE SCENE: THE AESTHETICS OF IGBO MASK THEATRE by VICTOR IKECHUKWU UKAEGBU A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Exeter School of Arts and Design Faculty of Arts and Education University of Plymouth May 1996. 90 0190329 2 11111 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior written consent. Date .. 3.... M.~~J. ... ~4:l~.:. VICTOR I. UKAEGBU. ii I 1 Unlversity ~of Plymouth .LibratY I I 'I JtemNo q jq . .. I I . · 00 . '()3''2,;lfi2. j I . •• - I '" Shelfmiul(: ' I' ~"'ro~iTHESIS ~2A)2;~ l)f(lr ' ' :1 ' I . I Thesis Abstract THE COMPOSITE SCENE: THE AESTHETICS OF IGBO MASK THEATRE by VICTOR IKECHUKWU UKAEGBU An observation of mask performances in Igboland in South-Eastern Nigeria reveals distinctions among displays from various communities. This is the product of a democratic society which encourages individualism and at the same time, sustains collectivism. This feature of Igbo masking has enriched and populated the Igbo theatrical scene with thousands of diverse and seemingly unconnected masking displays. Though these peculiarities do not indicate conceptual differences or imperfections, the numerous Igbo dialects and sub-cultural differences have not helped matters. Earlier studies by social anthropologists and a few theatre practitioners followed these differentials by focusing on particular masking types and sections of Igboland. -

For Reinstating/Constructing Damaged, Washed Away & Missing 23

Public Disclosure Authorized IMO STATE GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA RURAL ACCESS AND MOBILITY PROJECT (RAMP2) Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) for Reinstating/Constructing Damaged, Washed Away & Missing 23 Public Disclosure Authorized nos River Crossings on the Rural Road Network in Imo State Public Disclosure Authorized Final Report Public Disclosure Authorized November 2019 i Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................ ii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................. iv List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ iv List of Plates................................................................................................................................................ v List of Annexes ........................................................................................................................................... v LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ................................................................................... vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... ii CHAPTER ONE ........................................................................................................................................ -

Rnment of Nigeria 2008 Budget Amendment 2008

2008 BUDGET RNMENT OF NIGERIA AMENDMENT 2008 BUDGET =N= TOTAL MINISTRY OF ENERGY 151,952,463,046 0430000 MINISTRY OF ENERGY (POWER) TOTAL ALLOCATION: 24,993,484,580 Classification No. EXPENDITURE ITEMS 043000001100001 TOTAL PERSONNEL COST 521,540,942 043000001100010 SALARY & WAGES - GENERAL 466,462,682 043000001100011 CONSOLIDATED SALARY 466,462,682 043000001200020 BENEFITS AND ALLOWANCES - GENERAL 0 043000001200021 RENT TOPSAL 043000001300030 SOCIAL CONTRIBUTION 55,078,260 043000001300031 NHIS 22,031,304 043000001300032 PENSION 33,046,956 043000002000100 TOTAL GOODS AND NON - PERSONAL SERVICES - GENERAL 1,064,022,248 043000002050110 TRAVELS & TRANSPORT - GENERAL 360,390,550 043000002050111 LOCAL TRAVELS & TRANSPORT 213,753,755 043000002050112 INTERNATIONAL TRAVELS & TRANSPORT 146,636,795 043000002060120 TRAVELS & TRANSPORT (TRAINING) - GENERAL 39,446,416 043000002060121 LOCAL TRAVELS & TRANSPORT 14,351,416 043000002060122 INTERNATIONAL TRAVELS & TRANSPORT 25,095,000 043000002100200 UTILITIES - GENERAL 47,522,527 043000002100201 ELECTRICITY CHARGES 11,285,243 043000002100202 TELEPHONE CHARGES 24,667,060 043000002100203 INTERNET ACCESS CHARGES 5,150,000 043000002100204 SATELLITES BROADCASTING ACCESS CHARGES 2,756,000 043000002100205 WATER RATES 2,205,000 043000002100206 SEWAGE CHARGES 1,459,224 043000002150300 MATERIALS & SUPPLIES - GENERAL 196,804,367 043000002150301 OFFICE MATERIALS & SUPPLIES 146,937,391 043000002150302 LIBRARY BOOKS & PERIODICALS 10,611,555 043000002150303 COMPUTER MATERIALS & SUPPLIES 14,100,188 043000002150304 PRINTING