The Osu Caste System in Isuochi, Abia State, Nigeria, 1956-2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bible Translation and Language Elaboration: the Igbo Experience

Bible Translation and Language Elaboration: The Igbo Experience A thesis submitted to the Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS), Universität Bayreuth, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Dr. Phil.) in English Linguistics By Uchenna Oyali Supervisor: PD Dr. Eric A. Anchimbe Mentor: Prof. Dr. Susanne Mühleisen Mentor: Prof. Dr. Eva Spies September 2018 i Dedication To Mma Ụsọ m Okwufie nwa eze… who made the journey easier and gave me the best gift ever and Dikeọgụ Egbe a na-agba anyanwụ who fought against every odd to stay with me and always gives me those smiles that make life more beautiful i Acknowledgements Otu onye adịghị azụ nwa. So say my Igbo people. One person does not raise a child. The same goes for this study. I owe its success to many beautiful hearts I met before and during the period of my studies. I was able to embark on and complete this project because of them. Whatever shortcomings in the study, though, remain mine. I appreciate my uncle and lecturer, Chief Pius Enebeli Opene, who put in my head the idea of joining the academia. Though he did not live to see me complete this program, I want him to know that his son completed the program successfully, and that his encouraging words still guide and motivate me as I strive for greater heights. Words fail me to adequately express my gratitude to my supervisor, PD Dr. Eric A. Anchimbe. His encouragements and confidence in me made me believe in myself again, for I was at the verge of giving up. -

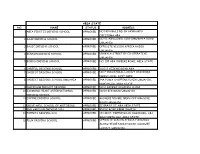

Abia State No

ABIA STATE NO. NAME STATUS ADDRESS 1 ABIA FIRST II DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 140 UMULE RD. BY UKWUAKPU OSISIOMA ABA. 2 AJAE DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 53 AWOLOWO SGBY UMUWAYA ROAD UMUAHIA 3 BASIC DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED OPPOSITE VISION AFRICA RADIO UMUAHIA 4 BENSON DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED UBAKALA STREET BY CO-OPERATIVE UMUAHIA 5 BOBOS DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO. 105 ABA OWEERI ROAD, ABIA STATE 6 CAREFUL DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED 111/113 AZIKWE ROAD ABA 7 CHIBEST DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 7 INDUSTRIAL LAYOUT OSISIOMA NGWA LOCAL GOVT AREA 8 CHIBEST DRIVING SCHOOL UMUAHIA APPROVED 34A POWA SHOPPING PLAZA UMUAHIA, NORTH LGA, ABIA STATE 9 CHINEDUM PRIVATE DRIVING APPROVED NO 2 AZIKWE OCHENDU CLOSE 10 DIAMOND HEART INTERNATIONAL APPROVED NO.10 BCA ROAD UMUAHIA DRIVING SCHOOL 11 DIVINE DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED AHIAEKE NDUME IBEKU OFF UMUSIKE ROAD UMUAHIA 12 DRIVE-WELL SCHOOL OF MOTORING, APPROVED 27 BRASS ST. ABA ABIA STATE. 13 ENG AMOSON DRIVING SCH APPROVED 95 FGC ROAD EBEM OHAFIA 14 EXPERTS DRIVING SCH APPROVED 133 IKOT- EKPENE ROAD OGBORHILL ABA, ABA NORTH LGA, ABIA STATE. 15 FLUX DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED OPPOSITE VISION AFRICA F.M RADIO ALONG SECRETARIAT ROAD, OGURUBE LAYOUT UMUAHIA 16 GIVENCHY DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 60 WARRI BY BENDER ROAD UMUAHIA, ABIA STATE. 17 HALLMARK DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED SUITE 4, 44-55 OSINULO SHOPPING COMPLEX ISI COURT UMUOBIA OLOKORO, UMUAHIA, ABIA STATE 18 IFEANYI DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED AMAWOM OBORO IKWUANO LGA 19 IJEOMA DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO.3 CHECHE CLOSE AMANGWU, OHAFIA, ABIA STATE 20 INTERNATIONAL DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO. 2 MECHANIC LAYOUT OFF CLUB ROAD UMUAHIA. -

Historical Dynamics of Ọjị Ezinihitte Cultural Festival in Igboland, Nigeria

67 International Journal of Modern Anthropology Int. J. Mod. Anthrop. 2020. Vol. 2, Issue 13, pp: 67 - 98 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ijma.v2i13.2 Available online at: www.ata.org.tn & https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ijma Research Article Historical dynamics of Ọjị Ezinihitte cultural festival in Igboland, Nigeria Akachi Odoemene Department of History and International Studies, Federal University Otuoke, Bayelsa State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] (Received 6 January 2020; Accepted 16 May 2020; Published 6 June 2020) Abstract - Ọjị (kola nut) is indispensable in traditional life of the Igbo of Nigeria. It plays an intrinsic role in almost all segments of the people‟s cultural life. In the Ọjị Ezinihitte festivity the „kola tradition‟ is meaningfully and elaborately celebrated. This article examines the importance of Ọjị within the context of Ezinihitte socio-cultural heritage, and equally accounts for continuity and change within it. An eclectic framework in data collection was utilized for this research. This involved the use of key-informant interviews, direct observation as well as extant textual sources (both published and un-published), including archival documents, for the purposes of the study. In terms of analysis, the study utilized the qualitative analytical approach. This was employed towards ensuring that the three basic purposes of this study – exploration, description and explanation – are well articulated and attained. The paper provided background for a proper understanding of the „sacred origin‟ of the Ọjị festive celebration. Through a vivid account of the festival‟s processes and rituals, it achieved a reconstruction of the festivity‟s origins and evolutionary trajectories and argues the festival as reflecting the people‟s spirit of fraternity and conviviality. -

Ph.D Thesis-A. Omaka; Mcmaster University-History

MERCY ANGELS: THE JOINT CHURCH AID AND THE HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE IN BIAFRA, 1967-1970 BY ARUA OKO OMAKA, BA, MA A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2014), Hamilton, Ontario (History) TITLE: Mercy Angels: The Joint Church Aid and the Humanitarian Response in Biafra, 1967-1970 AUTHOR: Arua Oko Omaka, BA (University of Nigeria), MA (University of Nigeria) SUPERVISOR: Professor Bonny Ibhawoh NUMBER OF PAGES: xi, 271 ii Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History ILLUSTRATIONS Figures 1. AJEEBR`s sponsored advertisement ..................................................................122 2. ACKBA`s sponsored advertisement ...................................................................125 3. Malnourished Biafran baby .................................................................................217 Tables 1. WCC`s sickbays and refugee camp medical support returns, November 30, 1969 .....................................................................................................................171 2. Average monthly deliveries to Uli from September 1968 to January 1970.........197 Map 1. Proposed relief delivery routes ............................................................................208 iii Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History ABSTRACT International humanitarian organizations played a prominent role -

SIGNIFICANCE of ANIMAL MOTIFS in INDIGENOUS ULI BODY and WALL PAINTINGS Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor Department of Fine and Applied A

Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies. Vol. 8, No. 1. June 2019 SIGNIFICANCE OF ANIMAL MOTIFS IN INDIGENOUS ULI BODY AND WALL PAINTINGS… Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor SIGNIFICANCE OF ANIMAL MOTIFS IN INDIGENOUS ULI BODY AND WALL PAINTINGS Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor Department of Fine and Applied Arts Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka. [email protected] This article explores the significance of animal motifs in traditional Uli body and wall paintings. A critical assessment and understanding of the philosophical import of animals in African concept of existence is vital for an in-depth appreciation of their (animals’) symbols in indigenous African artworks. This paper attempts to a draw parallel between traditional beliefs concerning certain animals among the Igbo of south-eastern Nigeria and motifs derived from indigenous Uli body and wall painting. In essence, the article sees animal motifs in Uli body and wall paintings as playing an aesthetic as well as metaphysical roles. Hence I argue that local nuances of religiosity and spirituality have historically imbued the animals with a heightened sense of sacredness in some Igbo communities thus allowing the animals to occupy a mystical space in Igbo cosmology. Introduction The pre-colonial system of knowledge transmission in Africa was not only through oral literature but also through the varied artistic traditions that survived from one generation to the other. The rich heritage of ancient Egyptian arts (including the hieroglyphs), the numerous Neolithic rock paintings and engravings found in Northern Africa, which dates back to 5000 and 2000 BCE respectively were mainly symbolic of vital occurrences of the past, documented through art (Getlein 2002: 335). -

The Igbo Traditional Food System Documented in Four States in Southern Nigeria

Chapter 12 The Igbo traditional food system documented in four states in southern Nigeria . ELIZABETH C. OKEKE, PH.D.1 . HENRIETTA N. ENE-OBONG, PH.D.1 . ANTHONIA O. UZUEGBUNAM, PH.D.2 . ALFRED OZIOKO3,4. SIMON I. UMEH5 . NNAEMEKA CHUKWUONE6 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems 251 Study Area Igboland Area States Ohiya/Ohuhu in Abia State Ubulu-Uku/Alumu in Delta State Lagos Nigeria Figure 12.1 Ezinifite/Aku in Anambra State Ede-Oballa/Ukehe IGBO TERRITORY in Enugu State Participating Communities Data from ESRI Global GIS, 2006. Walter Hitschfield Geographic Information Centre, McGill University Library. 1 Department of 3 Home Science, Bioresources Development 5 Nutrition and Dietetics, and Conservation Department of University of Nigeria, Program, UNN, Crop Science, UNN, Nsukka (UNN), Nigeria Nigeria Nigeria 4 6 2 International Centre Centre for Rural Social Science Unit, School for Ethnomedicine and Development and of General Studies, UNN, Drug Discovery, Cooperatives, UNN, Nigeria Nsukka, Nigeria Nigeria Photographic section >> XXXVI 252 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems | Igbo “Ndi mba ozo na-azu na-anwu n’aguu.” “People who depend on foreign food eventually die of hunger.” Igbo saying Abstract Introduction Traditional food systems play significant roles in maintaining the well-being and health of Indigenous Peoples. Yet, evidence Overall description of research area abounds showing that the traditional food base and knowledge of Indigenous Peoples are being eroded. This has resulted in the use of fewer species, decreased dietary diversity due wo communities were randomly to household food insecurity and consequently poor health sampled in each of four states: status. A documentation of the traditional food system of the Igbo culture area of Nigeria included food uses, nutritional Ohiya/Ohuhu in Abia State, value and contribution to nutrient intake, and was conducted Ezinifite/Aku in Anambra State, in four randomly selected states in which the Igbo reside. -

South South 2014 Federal Capital Budget

2014 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET Of the States in the South-South Geo-Political Zone By Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) 2014 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET Of the States in the South-South Geo-Political Zone Compiled by Centre for Social Justice For Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) ii First Published in October 2014 By Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) C/o Centre for Social Justice 17 Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja. Website: www.csj-ng.org ; E-mail: [email protected] ; Facebook: CSJNigeria; Twitter:@censoj; YouTube: www.youtube.com/user/CSJNigeria. iii Table of Contents Acknowledgement v Foreword vi Delta State 1 Akwa Ibom State 12 Bayelsa State 21 Cross River State 29 Edo State 42 River State 52 iv Acknowledgement Citizens Wealth Platform acknowledges the financial and secretariat support of Centre for Social Justice towards the publication of this Capital Budget Pull-Out v PREFACE This is the third year of compiling Capital Budget Pull-Outs for the six geo-political zones by Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP). The idea is to provide information to all classes of Nigerians about capital projects in the federal budget which have been appropriated for their zone, state, local government and community. There have been several complaints by citizens about the large bulk of government budgets which makes them unattractive and not reader friendly. Yes, it is difficult to wade through a maze of figures in a 2000 page document laden with accounting codes and numeric language. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Nigeria Conflict Re-Interview (Emergency Response

This PDF generated by kmcgee, 8/18/2017 11:01:05 AM Sections: 11, Sub-sections: 0, Questionnaire created by akuffoamankwah, 8/2/2017 7:42:50 PM Questions: 130. Last modified by kmcgee, 8/18/2017 3:00:07 PM Questions with enabling conditions: 81 Questions with validation conditions: 14 Shared with: Rosters: 3 asharma (never edited) Variables: 0 asharma (never edited) menaalf (never edited) favour (never edited) l2nguyen (last edited 8/9/2017 8:12:28 PM) heidikaila (never edited) Nigeria Conflict Re- interview (Emergency Response Qx) [A] COVER No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 18, Static texts: 1. [1] DISPLACEMENT No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 6. [2] HOUSEHOLD ROSTER - BASIC INFORMATION No sub-sections, Rosters: 1, Questions: 14, Static texts: 1. [3] EDUCATION No sub-sections, Rosters: 1, Questions: 3. [4] MAIN INCOME SOURCE FOR HOUSEHOLD No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 14, Static texts: 1. [5] MAIN EMPLOYMENT OF HOUSEHOLD No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 6, Static texts: 1. [6] ASSETS No sub-sections, Rosters: 1, Questions: 12, Static texts: 1. [7] FOOD AND MARKET ACCESS No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 21. [8] VULNERABILITY MEASURE: COPING STRATEGIES INDEX No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 6. [9] WATER ACCESS AND QUALITY No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 22. [10] INTERVIEW RESULT No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 8, Static texts: 1. APPENDIX A — VALIDATION CONDITIONS AND MESSAGES APPENDIX B — OPTIONS LEGEND 1 / 24 [A] COVER Household ID (hhid) NUMERIC: INTEGER hhid SCOPE: IDENTIFYING -

World Bank Document

RAMP -2: Procurement Plan – Jan. 2017. (RURAL ROADS AND MOBILTY PROJECT-2 PP:2017) Public Disclosure Authorized I. General 1. Project Information: Country: Nigeria Borrower: Federal Government of Nigeria Project Name: Rural Road and Mobility Project 2 (RAMP2). Loan/Credit No.: P095003 PIA: Federal Project Management Unit (FPMU) 2. Bank’s approval Date of the procurement Plan [Original: December 2007]: Revision of Updated Procurement Plan, June 2010]. Updated January 2017 2. Date of General Procurement Notice: Dec 24, 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized 3. Period covered by initial procurement plans: The procurement period of project covered from year June 2010 to December 2012; (Period covered by this current procurement plan: and January 2017 to December 2017 and or to June 2018). II. Goods and Works and non-consulting services. 1. Prior Review Threshold: Procurement Decisions subject to Prior Review by the Bank as stated in Appendix 1 to the Guidelines for Procurement: Public Disclosure Authorized Procurement Method Prior Review Threshold Comment (US$ equivalent) 1. ICB and LIB (Goods and services other > 1,000,000.00 ALL than consultancy services) 2. NCB (Goods) 100,000.00 ≤ 1,000,000.00 NONE 3 IT System, and Non-Consulting Services > 1,000,000.00 (ICB). NCB: 100,000.00 ≤ 1,000,000.00 4. ICB (Works) > 10,000,000.00 ALL 5. NCB (Works) 300,000 ≤ 10,000,000.00 NONE 6 Shopping-Goods < 100,000.00 NONE 7 Shopping-Works < 300,000.00 NONE 8. Community Participation in All Values SSS of Community Procurement acceptable to the Maintenance Association and described in the PIM Public Disclosure Authorized groups, etc. -

The Hermeneutics of Women Disciples in Mark's Gospel: an Igbo Contextual Reconstruction

The Hermeneutics of Women Disciples in Mark's Gospel: An Igbo Contextual Reconstruction Author: Fabian Ekwunife Ezenwa Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:108068 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2018 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. THE HERMENEUTICS OF WOMEN DISCIPLES IN MARK’S GOSPEL: AN IGBO CONTEXTUAL RECONSTRUCTION A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE LICENTIATE IN SACRED THEOLOGY (S.T.L) DEGREE FROM THE BOSTON COLLEGE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AND MINISTRY BY EZENWA FABIAN EKWUNIFE, C.S.SP MENTOR: DR ANGELA KIM HARKINS CO-MENTOR: PROF. MARGARET E. GUIDER, OSF MAY 3, 2018 BOSTON COLLEGE | Ezenwa, C.S.Sp DEDICATION TO MY MOTHER, MARCELINA EZENWA (AKWUGO UMUAGBALA) AND ALL UMUADA IGBO i | Ezenwa, C.S.Sp TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………….1 CHAPTER ONE: SCHOLARSHIP REVIEW ………………………………………….…..9 1.1. QUESTION ABOUT MARK’S PORTRAIT OF WOMEN ………………………….…..10 1.2. QUESTION ABOUT THE APPROACH AND PARADIGM OF INVESTIGATION ......18 1.3. CHALLENGING THE CONCEPT, “ἩO MATHĒTAI” (“THE DISCIPLES”) ……..…..24 CONCLUSION ………………………………………………………………………………...30 CHAPTER TWO: IGBO CULTURAL STUDY IN CONTEXT …………………….....…32 2.1. DEVELOPMENT OF BIBLICAL CRITICISM ……………………………………......…33 2.2. IGBO COMMUNITY CONSCIOUSNESS, THE “NWANNE” PHILOSOPHY OF LIFE.35 2.3. THE IGBO PEOPLE OF NIGERIA ………………………………………………………39 2.3.1. WHO ARE THE IGBO? …………………………………………………………….….39 2.3.2. SOCIO-POLITICAL LIFE OF THE IGBO ……………………………………….…....40 2.3.3. IGBO WORLDVIEW ……………………………………………………………….….42 2.3.4. IGBO PATRIARCHY ………………………………………………………………….44 2.3.5. ROLES PLAYED BY INDIVIDUALS IN IGBO SOCIETY ……………………….....47 2.3.6. -

Encoded Language As Powerful Tool. Insights from Okǝti Ụmụakpo-Lejja Ọmaba Chant

Journal of Language and Cultural Education, 2020, 8(3) ISSN 1339-4584 DOI: 10.2478/jolace-2020-0025 Traditional Segregation: Encoded Language as Powerful Tool. Insights from Okǝti Ụmụakpo-Lejja Ọmaba chant Uchechukwu E. Madu Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Nigeria [email protected] Abstract Language becomes a tool for power and segregation when it functions as a social divider among individuals. Language creates a division between the educated and uneducated, an indigene and non-indigene of a place; an initiate and uninitiated member of a sect. Focusing on the opposition between expressions and their meanings, this study examines Ụmụakpo- Lejja Okǝti Ọmaba chant, which is a heroic and masculine performance that takes place in the Okǝti (masking enclosure of the deity) of Umuakpo village square in Lejja town of Enugu State, Nigeria. The mystified language promotes discrimination among initiates, non- initiates, and women. Ọmaba is a popular fertility Deity among the Nsukka-Igbo extraction and Egara Ọmaba (Ọmaba chant) generally applies to the various chants performed to honour the deity during its periodical stay on earth. Using Schleiermacher’s Literary Hermeneutics Approach of the methodical practice of interpretation, the metaphorical language of the performance is interpreted to reveal the thoughts and the ideology behind the performance in totality. Among the Findings is that the textual language of Ụmụakpo- Lejja Okǝti Ọmaba chant is almost impossible without authorial and member’s interpretation and therefore, they are capable of initiating discriminatory perception of a non-initiate as a weakling or a woman. Keywords: Ọmaba chant, Ụmụakpo-Lejja, language, power, hermeneutics Introduction Beyond the primary function of language, which is the expression and communication of one’s ideas, a language is also a tool for power, segregation, and division in society.