Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court Merits Stage Amicus Brief

i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ..............................1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT...................................2 ARGUMENT .............................................................4 I. THE PRIVILEGES OR IMMUNITIES CLAUSE OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT PROTECTS SUBSTANTIVE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AGAINST STATE INFRINGEMENT…………………....4 A. Crafted Against A Backdrop Of Rights- Suppression In The South, The Privileges Or Immunities Clause Was Written To Protect Substantive Fundamental Rights……………………………………………4 B. By 1866, The Public Meaning Of “Privileges” And “Immunities” Included Fundamental Rights………………………….8 C. The Congressional Debates Over The Fourteenth Amendment Show That The Privileges Or Immunities Clause Encompassed Substantive Fundamental Rights, Including The Personal Rights In The Bill Of Rights……………………………14 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS—continued D. The Wording Of The Privileges Or Immunities Clause Is Broader Than The Privileges And Immunities Clause Of Article IV…………………………………….. 21 II. THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT’S PRIVILEGES OR IMMUNITIES CLAUSE INCLUDED AN INDIVIDUAL RIGHT TO BEAR ARMS…………………………………. 24 III. PRECEDENT DOES NOT PREVENT THE COURT FROM RECOGNIZING THAT THE PRIVILEGES OR IMMUNITIES CLAUSE PROTECTS AN INDIVIDUAL RIGHT TO BEAR ARMS AGAINST STATE INFRINGEMENT…………………………... 29 A. Slaughter-House And Its Progeny Were Wrong As A Matter Of Text And History And Have Been Completely Undermined -

The Attorney General's Ninth Annual Report to Congress Pursuant to The

THE ATTORNEY GENERAL'S NINTH ANNUAL REPORT TO CONGRESS PURSUANT TO THE EMMETT TILL UNSOLVED CIVIL RIGHTS CRIME ACT OF 2007 AND THIRD ANNUALREPORT TO CONGRESS PURSUANT TO THE EMMETT TILL UNSOLVEDCIVIL RIGHTS CRIMES REAUTHORIZATION ACT OF 2016 March 1, 2021 INTRODUCTION This is the ninth annual Report (Report) submitted to Congress pursuant to the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of2007 (Till Act or Act), 1 as well as the third Report submitted pursuant to the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Reauthorization Act of 2016 (Reauthorization Act). 2 This Report includes information about the Department of Justice's (Department) activities in the time period since the eighth Till Act Report, and second Reauthorization Report, which was dated June 2019. Section I of this Report summarizes the historical efforts of the Department to prosecute cases involving racial violence and describes the genesis of its Cold Case Int~~ative. It also provides an overview ofthe factual and legal challenges that federal prosecutors face in their "efforts to secure justice in unsolved Civil Rights-era homicides. Section II ofthe Report presents the progress made since the last Report. It includes a chart ofthe progress made on cases reported under the initial Till Act and under the Reauthorization Act. Section III of the Report provides a brief overview of the cases the Department has closed or referred for preliminary investigation since its last Report. Case closing memoranda written by Department attorneys are available on the Department's website: https://www.justice.gov/crt/civil-rights-division-emmett till-act-cold-ca e-clo ing-memoranda. -

The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2012 I'm Really Just an American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness Shea Aisha Winsett College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Winsett, Shea Aisha, "I'm Really Just an American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness" (2012). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626687. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-tesy-ns27 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I’m Really Just An American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness Shea Aisha Winsett Hyattsville, Maryland Bachelors of Arts, Oberlin College, 2008 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department -

The Creation and Destruction of the Fourteenth Amendment Duringthe Long Civil War

Louisiana Law Review Volume 79 Number 1 The Fourteenth Amendment: 150 Years Later Article 9 A Symposium of the Louisiana Law Review Fall 2018 1-24-2019 The Creation and Destruction of the Fourteenth Amendment Duringthe Long Civil War Orville Vernon Burton Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Orville Vernon Burton, The Creation and Destruction of the Fourteenth Amendment Duringthe Long Civil War, 79 La. L. Rev. (2019) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol79/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Creation and Destruction of the Fourteenth Amendment During the Long Civil War * Orville Vernon Burton TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................. 190 I. The Civil War, Reconstruction, and the “New Birth of Freedom” ............................................................. 192 A. Lincoln’s Beliefs Before the War .......................................... 193 B. Heading into Reconstruction ................................................. 195 II. The Three Reconstruction Amendments ...................................... 196 A. The Thirteenth Amendment .................................................. 197 B. The South’s -

Badges of Slavery : the Struggle Between Civil Rights and Federalism During Reconstruction

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2013 Badges of slavery : the struggle between civil rights and federalism during reconstruction. Vanessa Hahn Lierley 1981- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Lierley, Vanessa Hahn 1981-, "Badges of slavery : the struggle between civil rights and federalism during reconstruction." (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 831. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/831 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BADGES OF SLAVERY: THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN CIVIL RIGHTS AND FEDERALISM DURING RECONSTRUCTION By Vanessa Hahn Liedey B.A., University of Kentucky, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, KY May 2013 BADGES OF SLAVERY: THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN CIVIL RIGHTS AND FEDERALISM DURING RECONSTRUCTION By Vanessa Hahn Lierley B.A., University of Kentucky, 2004 A Thesis Approved on April 19, 2013 by the following Thesis Committee: Thomas C. Mackey, Thesis Director Benjamin Harrison Jasmine Farrier ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my husband Pete Lierley who always showed me support throughout the pursuit of my Master's degree. -

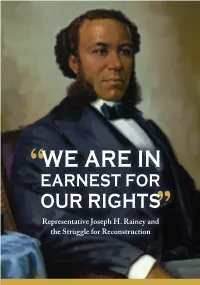

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFO RM A TIO N TO U SER S This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film s the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fromany type of con^uter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependentquality upon o fthe the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and inqjroper alignment can adverse^ afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note wiD indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one e3q)osure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photogr^hs included inoriginal the manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for aiy photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI direct^ to order. UMJ A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.'761-4700 800/521-0600 LAWLESSNESS AND THE NEW DEAL; CONGRESS AND ANTILYNCHING LEGISLATION, 1934-1938 DISSERTATION presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Robin Bernice Balthrope, A.B., J.D., M.A. -

A War All Our Own: American Rangers and the Emergence of the American Martial Culture

A War All Our Own: American Rangers and the Emergence of the American Martial Culture by James Sandy, M.A. A Dissertation In HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTORATE IN PHILOSOPHY Approved Dr. John R. Milam Chair of Committee Dr. Laura Calkins Dr. Barton Myers Dr. Aliza Wong Mark Sheridan, PhD. Dean of the Graduate School May, 2016 Copyright 2016, James Sandy Texas Tech University, James A. Sandy, May 2016 Acknowledgments This work would not have been possible without the constant encouragement and tutelage of my committee. They provided the inspiration for me to start this project, and guided me along the way as I slowly molded a very raw idea into the finished product here. Dr. Laura Calkins witnessed the birth of this project in my very first graduate class and has assisted me along every step of the way from raw idea to thesis to completed dissertation. Dr. Calkins has been and will continue to be invaluable mentor and friend throughout my career. Dr. Aliza Wong expanded my mind and horizons during a summer session course on Cultural Theory, which inspired a great deal of the theoretical framework of this work. As a co-chair of my committee, Dr. Barton Myers pushed both the project and myself further and harder than anyone else. The vast scope that this work encompasses proved to be my biggest challenge, but has come out as this works’ greatest strength and defining characteristic. I cannot thank Dr. Myers enough for pushing me out of my comfort zone, and for always providing the firmest yet most encouraging feedback. -

The Making of Federal Enforcement Laws, 1870-1872 - Freedom: Political

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 70 Issue 3 Symposium on the Law of Freedom Part Article 6 II: Freedom: Beyond the United States April 1995 The Making of Federal Enforcement Laws, 1870-1872 - Freedom: Political X1 Wang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation X1 Wang, The Making of Federal Enforcement Laws, 1870-1872 - Freedom: Political, 70 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 1013 (1995). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol70/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE MAKING OF FEDERAL ENFORCEMENT LAWS, 1870-1872* XI WANG** The Fifteenth Amendment represented the highest achievement of the Republican party's Reconstruction politics. By prohibiting the national and state governments from depriving citizens of the right to vote on the basis of race, color, and previous condition of servitude, the Amendment conferred suffrage on newly emancipated African- American men, thus constitutionalizing the principle and practice of black suffrage which was first established in early 1867. Black partici- pation in Reconstruction not only helped to consolidate the outcomes of the Civil War and congressional Reconstruction, but it also rede- fined the course of American democracy. In order to maintain the vitality and validity of the Fifteenth Amendment, the Republican party had to permanently and effectively implement that Amendment in the South, where anti-black suffrage forces mounted high. -

Domestic Constitutional Violence

University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review Volume 41 Issue 2 The Ben J. Altheimer Symposium-- Article 3 Cooper v. Aaron: Still Timely at Sixty Years 2019 Domestic Constitutional Violence F. E. Guerra-Pujol Follow this and additional works at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation F. E. Guerra-Pujol, Domestic Constitutional Violence, 41 U. ARK. LITTLE ROCK L. REV. 211 (2019). Available at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview/vol41/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review by an authorized editor of Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOMESTIC CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLENCE F. E. Guerra-Pujol I. INTRODUCTION We often associate violence with extra-legal behavior1 or with the dark side of law enforcement.2 But violence has also played a pivotal role in our nation’s history and in the development of constitutional law. Simply put, our government has often resorted to acts of “constitutional violence”3 to effectuate major constitutional change. Consider the stain of slavery. From a practical perspective, it was not the formal enactment of the Thirteenth Amendment that eradicated this peculiar institution. Rather, it was the blood spilled in such costly battles as Bull Run, Chickamauga, and Gettysburg that settled the festering constitutional question of slavery once and for all.4 The same logic applies to school desegregation and the Little Rock Crisis of 1957. -

HISTORICAL ARGUMENTATION… African Americans in the Civil War (See Writing Guidelines in Your Binder for Formula)

Name:_______________________________________________________________ Class Period:____ APUSH Unit 4, College Board Period 5 HISTORICAL ARGUMENTATION… African Americans in the Civil War (see writing guidelines in your binder for formula) Step #1 Read the question or prompt carefully: Read the question three times and be able to paraphrase the question and know the essential task demanded by it. Answering the question will be the central focus of your essay, and you want to be sure to ATFP: Address The Full Prompt. Prompt: In what ways and to what extent did African American efforts during the Civil War and Reconstruction eras maintain continuity or foster change? Confine your answer to the years 1861-1870. Step #2 Brainstorm on paper everything that comes to mind regarding the topic at hand. Review the timeline on the back of this page for additional review, but do not depend solely on the timeline. Aim for at least 10 specific things. What do you know about the topic? Put this down on paper to get your brain in gear for writing the essay. Once you have amble information, categorize it by theme. (ABC) 1. 6. 2. 7. 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10. Step #3 Clarify your thesis/view and identify an opposing view. Make sure your thesis ATFP! Don’t restate the prompt! Y: X: Step #4 Write your introductory paragraph. USE THE FORMULA Historical Analysis Activity written by Rebecca Richardson, Allen High School using the 2012 College Board APUSH Framework and an adaption of a 2009 College Board released exam Name:_______________________________________________________________ Class Period:____ APUSH Unit 4, College Board Period 5 1861 -Civil War erupts at Fort Sumter. -

The Political Problems in Mississippi During the Reconstruction Period 1863-1876

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1949 The Political Problems in Mississippi During the Reconstruction Period 1863-1876 John J. Beckman Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Beckman, John J., "The Political Problems in Mississippi During the Reconstruction Period 1863-1876" (1949). Master's Theses. 733. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/733 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1949 John J. Beckman The Political Problems in Mississippi during the Reconstruction Period 1863 - 1876 by John J. Beckman, S.J. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LOYOLA UNIVERSITY JUNE 1949 Vita Auctoris John J. Beckman, S.J. was born in Cincinnati Ohio, February 25, 1921. He attended Holy Family Parochial School where he completed his elementary education in 1935. Four years later he was graduated from St. Xavier High School, CinCinnati, Ohio. He then attended xavier University, CinCinnati, Ohio, where in January, 1943, he received his degree of Bachelor of Arts in History. In February of the same year he entered the Novitiate of the Sacred Heart, Milford, Ohio. In the fall of 1946 he registered in Loyola University graduate school, at the same time furthering his study of philosophy at West Baden College, West Baden Springs, Indiana, an affiliated College.