Bargaining, Sorting, and the Gender Wage Gap: Quantifying the Impact of Firms on the Relative Pay of Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information About Unemployment Insurance for Workers on Temporary Layoff

Information about Unemployment Insurance for Workers on Temporary Layoff What is a Temporary Layoff? A temporary layoff occurs when you are partially unemployed because of lack of work or you have worked less than the equivalent of 3 customary, scheduled, full-time days for your plant or industry and earn less than your ineligible amount (earnings allowance plus your weekly benefit amount).Your employer will notify you when a temporary layoff occurs or is pending, and will prepare the information needed to file for temporary unemployment insurance benefits. Your employer is allowed to file a temporary layoff claim only once during your benefit year and this one occurrence is limited to a maximum of 6 consecutive weeks. The first week of this series is a waiting period week for which no benefits can be paid. After this six week period has passed (if you are still unemployed) you will need to file your own claim for unemployment benefits. What Happens Next? After your new claim is filed, you will be mailed Form N CUI-550, Wage Transcript and Monetary Determination. This form shows the employer(s) for whom you worked during the base period applicable to your claim, and the amount of wages they paid you during each quarter. It also shows the weekly amount of benefits payable to you and the number of weeks for which benefits may be paid during your benefit year. Currently, the maximum weekly benefit amount payable is $350 per week. The number of weeks payable at the full weekly benefit amount varies based on the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate. -

Employment Downsizing and Its Alternatives

SHRM Foundation’s Effective Practice Guidelines Series Employment Downsizing and its Alternatives STRATEGIES FOR LONG-TERM SUCCESS Sponsored by Right Management SHRM FOUNDAtion’S EFFECTIVE PraCTICE GUIDELINES SERIES Employment Downsizing and its Alternatives STRATEGIES FOR LONG-TERM SUCCESS Wayne F. Cascio Sponsored by Right Management Employment Downsizing and its Alternatives This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information regarding the subject matter covered. Neither the publisher nor the author is engaged in rendering legal or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent, licensed professional should be sought. Any federal and state laws discussed in this book are subject to frequent revision and interpretation by amendments or judicial revisions that may significantly affect employer or employee rights and obligations. Readers are encouraged to seek legal counsel regarding specific policies and practices in their organizations. This book is published by the SHRM Foundation, an affiliate of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM©). The interpretations, conclusions and recommendations in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the SHRM Foundation. ©2009 SHRM Foundation. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. This publication may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the SHRM Foundation, 1800 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA 22314. The SHRM Foundation is the 501(c)3 nonprofit affiliate of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). -

Notice of Layoff Or Reassignment

Attachment B DHRM Form L-1 First Notice Rev. 10/07 Commonwealth of Virginia Final Notice Notice of Layoff or Placement This section is to be completed by the agency human resource officer Agency Name Date Employee Employee ID Name Number Position Role SOC Code Number Pay Current Semi-Monthly Band Salary Effective , you are being placed in the following position: Role SOC Code Position Number Location Semi-Monthly Salary are being placed on leave without pay-layoff for up to 12 months because there is no placement opportunity available to you under the State Layoff Policy. If you are being placed, options available to you are marked with an X below. You may decline the placement if it requires relocating your residence, and proceed to the next placement opportunity available to you under the Layoff Policy, if any other options are available. If none are available, I will be placed on leave without pay-layoff for up to 12 months. You may decline the placement since it is to a position that will result in a salary decrease, and request that you be placed on leave without pay-layoff for up to 12 months. If you do not accept the placement, your only option is to be separated-layoff because it will not result in salary decrease or need to relocate. You will not be entitled to severance benefits. Signed Title This section is to be filled in by the employee and returned to the human resource officer no later than . If you do not return the form by this date, agency management will determine your placement. -

Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES WHERE IS THE LAND OF OPPORTUNITY? THE GEOGRAPHY OF INTERGENERATIONAL MOBILITY IN THE UNITED STATES Raj Chetty Nathaniel Hendren Patrick Kline Emmanuel Saez Working Paper 19843 http://www.nber.org/papers/w19843 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 January 2014 The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Internal Revenue Service, the U.S. Treasury Department, or the National Bureau of Economic Research. This work is a component of a larger project examining the effects of tax expenditures on the budget deficit and economic activity. All results based on tax data in this paper are constructed using statistics originally reported in the SOI Working Paper "The Economic Impacts of Tax Expenditures: Evidence from Spatial Variation across the U.S.," approved under IRS contract TIRNO-12-P-00374 and presented at the National Tax Association meeting on November 22, 2013. We thank David Autor, Gary Becker, David Card, David Dorn, John Friedman, James Heckman, Nathaniel Hilger, Richard Hornbeck, Lawrence Katz, Sara Lalumia, Adam Looney, Pablo Mitnik, Jonathan Parker, Laszlo Sandor, Gary Solon, Danny Yagan, numerous seminar participants, and four anonymous referees for helpful comments. Sarah Abraham, Alex Bell, Shelby Lin, Alex Olssen, Evan Storms, Michael Stepner, and Wentao Xiong provided outstanding research assistance. This research was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Lab for Economic Applications and Policy at Harvard, the Center for Equitable Growth at UC-Berkeley, and Laura and John Arnold Foundation. Publicly available portions of the data and code, including intergenerational mobility statistics by commuting zone and county, are available at www.equality-of-opportunity.org. -

The Essential Guide to Handling a Layoff Table of Contents

Tools, tips, and templates to ensure a smooth transition The Essential Guide to Handling a Layoff Table of Contents Section One: How to Select Who to Layoff 05 Employee Layoff Selection Guide Multi–Criteria Layoff Selection Guide Section Two: Worker Adjustment & Retraining Notification 14 Checklist Sample Letter Section Three: How to Layoff an Employee 18 Reduction Checklist Layoff Script Layoff Letter / Layoff Memo / Layoff Form Severance Pay Policy / Severance Calculator Offboarding Checklist Exit Interview Questionnaire How to handle a layoff with confidence and care Careful planning and preparation are key to successfully managing a layoff. But too often, the day-to-day demands of a busy workplace leave little opportunity to put in place the information and materials that allow an employer to ease — for everyone involved — the turmoil a layoff can bring. That’s why this ebook has been created. Making the hard choices For managers and HR professionals, having to let people go is one of the most difficult parts of the job, even when it’s clear that it’s a necessary step. And for employees directly impacted by that decision, a layoff is not only difficult, but it can also initially be devastating, especially when loyal and productive employees have to be let go due to a company’s decision to downsize in order to remain viable. A reduction in force is also likely to affect the morale of the employees who remain on the job. As tough as layoffs can be, it is possible to do them in ways that make things easier on everyone — ways that illustrate for laid-off employees the fact that the company cares about them as people; ways that also leave remaining employees feeling reassured by the way a layoff has been handled. -

Qt3sd0f741.Pdf

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Essays in Labor Economics and the Criminal Justice System Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3sd0f741 Author Shem-Tov, Yotam Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Essays in Labor Economics and the Criminal Justice System by Yotam Shem-Tov A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Patrick Kline, Chair Professor David Card Professor Steven Raphael Professor Christopher Walters Spring 2019 Essays in Labor Economics and the Criminal Justice System Copyright 2019 by Yotam Shem-Tov 1 Abstract Essays in Labor Economics and the Criminal Justice System by Yotam Shem-Tov Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Patrick Kline, Chair This dissertation investigates key aspects of the U.S. criminal justice system. The first chapter studies different methods of providing a legal counsel to low-income criminal defendants. Most criminal defendants in the U.S. cannot afford to hire an attorney. To provide constitutionally mandated legal services, states commonly use either private court-appointed attorneys or a public defender organization. This paper investigates the relative efficacy of these two modes of indigent defense by comparing outcomes of co- defendants assigned to different types of attorneys within the same case. Using data from San Francisco, I show that in multiple defendant cases public defender assignment is plausibly as good as random. I find that defendants who have been assigned a public defenders obtain more favorable sentencing outcomes. -

57 ARTICLE 26: LAYOFF A. General Provisions the Employer Shall

ARTICLE 26: LAYOFF A. General Provisions The Employer shall determine when temporary or indefinite layoffs are necessary. B. Definitions 1. Temporary layoff affecting a career position is for a specified period of less than four (4) calendar months from the date of layoff. 2. Indefinite layoff affecting a career position is one which is four (4) or more calendar months. C. Temporary Layoff 1. An employee shall be given written notice of the effective date and the ending date of a temporary layoff. The notice shall be given at least thirty (30) calendar days prior to the effective date. D. Indefinite Layoff 1. The order of layoff for indefinite career employees in the same classification (defined as the four (4) digits of the title code) within a unit defined by the Employer is in inverse order of seniority except that the department head may retain employees irrespective of seniority who possess special skills, knowledge, or abilities that are not possessed by other employees in the same classification with greater seniority, and that are necessary to perform the ongoing function of the department. 2. Seniority: Seniority shall be calculated by the number of career full-time equivalent months (or hours) of LLNL service. Employment prior to a break in service shall not be counted. When employees have the same number of full-time equivalent months (or hours), the employee with the most recent date of appointment shall be deemed the least senior. 3. Notice: An employee will receive at least thirty (30) calendar days written notice prior to indefinite layoff. If less than thirty (30) calendar days notice is provided, the employee shall receive straight-time pay in lieu of notice for each additional day the employee would have been on pay status had the employee been given thirty (30) calendar days notice. -

Reemploying Displaced Adults

Technology and Structural Unemployment: Reemploying Displaced Adults February 1986 NTIS order #PB86-206174 'iffii©1Jl0il@~@®11 ';:'Oil", >:;1iWl!!l©1(:Woo&~ l!!l Oil 1liil£1m@111l11li1m1i', REEMPLOYING DISPLACED ADULTS 'iil'-.-- ~:::.::::':::" - Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Technology and Structural Unem- ployment: Reemploying Displaced Adults, OTA-ITE-250 (Washington, DC: U.S. Gov- ernment Printing Office, February 1986). Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 85-600631 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 Foreword The problems of displaced adults have received increasing attention in the 1980s, as social, technological, and economic changes have changed the lifestyles of mil- lions of Americans. Displaced adults are workers who have lost jobs through no fault of their own, or homemakers who have lost their major source of financial support. In October 1983 OTA was asked by the Senate Committee on Finance and the Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources to assess the reasons and out- look for adult displacement, to evaluate the performance of existing programs to serve displaced adults, and to identify options to improve service. In June 1984, the House Committee on Small Business asked OTA to include in the study an ex- amination of trends in international trade and their effects on worker displacement. Worker displacement will continue to be an important issue for the remainder of the decade and beyond, as the U.S. economy adapts to rapid changes in inter- national competition, trade, and technology. While increasing automation and other industry adjustments to new competitive forces benefit the Nation as a whole, they do mean that millions of workers are displaced. -

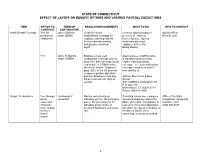

Effect of Layoff on Benefit Options and Various Payroll Deductions April 2016

STATE OF CONNECTICUT EFFECT OF LAYOFF ON BENEFIT OPTIONS AND VARIOUS PAYROLL DEDUCTIONS ITEM OPTION TO TERM OF REGULATIONS/COMMENTS WHAT TO DO WHO TO CONTACT CONTINUE CONTINUATION Health/Dental Coverage Yes, for Up to 4 Months Continue current Continue paying employee Agency HR or permanent under SEBAC health/dental coverage for p r e m i u m share to Benefits Unit employees employee and dependents former Agency. Agency for four calendar months, must manually enroll including the month of employee in Benefits layoff. Billing Module. Yes Up to 30 Months Employee must elect Agency issues COBRA notice under COBRA continuation coverage w/in 60 & enrollment form to each days from date coverage would eligible individual losing end or date of COBRA notice, coverage. To elect continuation whichever is later. Employee coverage complete & submit pays 102% of the full premium form directly to: (employee portion plus state portion). Employee must pay Anthem Blue Cross & Blue full premium w/in 45 days of Shield election. Attn: COBRA Continuation Unit P.O. Box 719 North Haven, CT 06473-0719 Phone: 800-433-5436 Group Life Insurance Yes, through Continuous if May be converted to an If electing conversion, employee Office of the State policy converted individual who le life insurance should immediately contact the Comptroller, Group Life conversion policy. The premiums for the Office of the State Comptroller to Insurance Unit (limited to individual policy will be at request a conversion application. (860) 702-3537 those in plan Dearborn National’s customary (Deadline to request is 30 days of for more rate. -

Coronavirus (Covid-19) District of Columbia Department of Employment Services Frequently Asked Questions for Employees

DOES CORONAVIRUS (COVID-19) DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT SERVICES FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS FOR EMPLOYEES 1. What if I need to take time off from work because I was exposed to COVID-19? Am I eligible for unemployment insurance benefits? Yes. If you are following guidance of a medical professional or public health official to isolate or quarantine yourself as a result of exposure to COVID-19 and you are not receiving paid sick leave from your employer, the District of Columbia will consider you entitled to unemployment benefits because you have reduced hours and pay. 2. What if I am asked by a medical professional or public health official to quarantine as a result of COVID-19, but I am not sick? Am I eligible for unemployment insurance benefits? Yes. If you are following guidance of a medical professional or public health official to isolate or quarantine yourself as a result of exposure to COVID-19 and you are not receiving paid sick leave from your employer, the District of Columbia will consider you entitled to unemployment benefits because you have reduced hours and pay. 3. My employer has shut down operations temporarily because an employee is sick and we have been asked to isolate or quarantine as a result of COVID-19. Am I eligible for unemployment insurance benefits? Yes. If your employer has shut down operations temporarily due to a COVID-19 related quarantine, the District of Columbia will consider this a temporary layoff as the employer does not currently have suitable work for you but intends to call you back to work once the quarantine has ended. -

Civil Rights and the Gender Wage Gap in Utah (2020)

Civil Rights and the Gender Wage Gap in Utah A Report of the Utah Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights July 2020 Advisory Committees to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights By law, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights has established an advisory committee in each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The committees are composed of state citizens who serve without compensation. The committees advise the Commission of civil rights issues in their states that are within the Commission’s jurisdiction. More specifically, they are authorized to advise the Commission in writing of any knowledge or information they have of any alleged deprivation of voting rights and alleged discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, national origin, or in the administration of justice; advise the Commission on matters of their state’s concern in the preparation of Commission reports to the President and the Congress; receive reports, suggestions, and recommendations from individuals, public officials, and representatives of public and private organizations to committee inquiries; forward advice and recommendations to the Commission, as requested; and observe any open hearing or conference conducted by the Commission in their states. Letter of Transmittal Utah Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights The Utah Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights submits this report on the gender wage gap in Utah. The Committee sought to understand factors that may cause or contribute to the gender wage gap; the impact of the wage gap on individuals on the basis of sex and race; and the impact of federal and state level enforcement efforts aimed to address pay inequity. -

Whistleblower Protection

WHISTLEBLOWER PROTECTION Workers have the right to complain to OSHA and seek an OSHA inspection. Section 11(c) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 (OSH Act) authorizes OSHA to investigate employee complaints of employer discrimination against those who are involved in safety and health activities. OSHA also is responsible for enforcing whistleblower protection under ten other laws. OSHA Area Office staff can explain the protections under these laws and the deadlines for filing complaints. Workers in the 23 states operating OSHA-approved State Plans may file complaints of employer discrimination with the state plan as well. State and local government workers in these states (and two others with public-employee only state plans) may file complaints of employer discrimination with the state. Types of Discrimination Some examples of discrimination include: ◆ Firing ◆ Demotion ◆ Transfer ◆ Layoff ◆ Losing opportunity for overtime or promotion ◆ Exclusion from normal overtime work ◆ Assignment to an undesirable shift ◆ Denial of benefits such as sick leave or vacation time ◆ Blacklisting with other employers ◆ Taking away company housing ◆ Damaging credit at banks or credit unions, and ◆ Reducing pay or hours. Refusal of Work When you believe working conditions are unsafe or unhealthful, you should call your employer's attention to the problem. If your employer does not correct the hazard or disagrees with you about the extent of the hazard, you may file a complaint with OSHA. Refusing to do a job because of potentially unsafe workplace conditions is not ordinarily an employee right under the OSH Act. (Your union contract or state law may, however, give you this right, but OSHA cannot enforce it.) Refusing to work may result in disciplinary action by the employer.