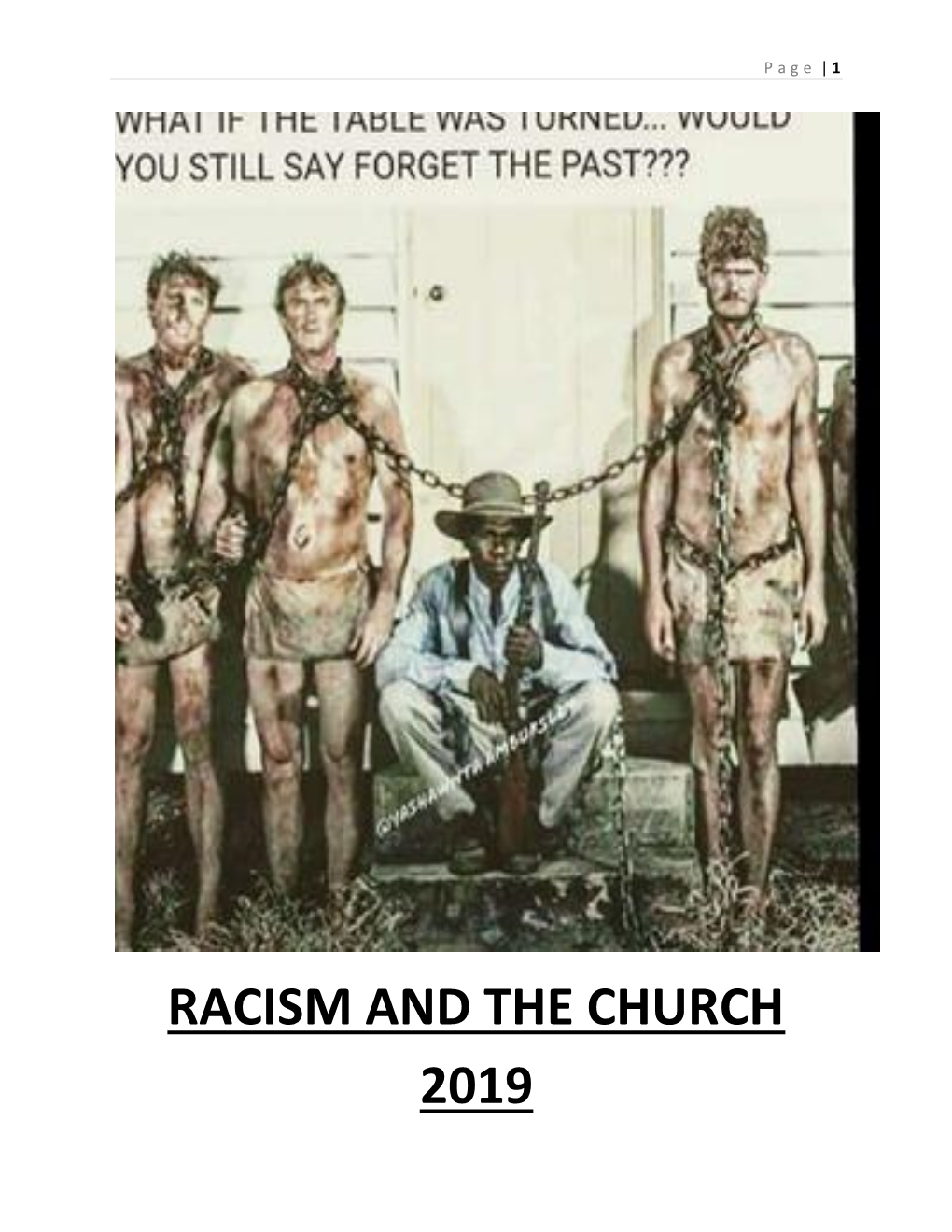

Racism and the Church 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MO4VR Response to VRAA Intro

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 17, 2021 CONTACT [email protected] March On for Voting Rights Responds to John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act Introduction in the House Martin Luther King III, Arndrea Waters King, Rev. Al Sharpton, Andi Pringle and other voting rights leaders organize mass mobilization to pass the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act Washington, D.C. — Today, standing on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Congresswoman Terri Sewell (D-AL) introduced the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, which will restore critical provisions of the Voting Rights Act gutted by the Supreme Court. Expected to receive a vote in the House of Representatives next week, the bill will help stem the rush of attacks on voting rights across the country by ensuring that states with a recent history of voter discrimination are once again subject to federal oversight. March On for Voting Rights will call on the Senate to pass the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act and the For the People Act on Saturday, August 28, when millions join the March On for Voting Rights in D.C., Phoenix, Atlanta, Houston, Miami and more than 40 other cities across the country to make their voices heard. Marchers will also call for the Senate to remove the filibuster as a roadblock to critical voting rights legislation. Rev. Al Sharpton, President and Founder of National Action Network, commented in response: “If you want to understand why the vote is so important, look at the last 4 years, the last 10 years, and the last 100 years. Freedom fighter and Congressman John Lewis knew it was essential that every vote must count in order to assure every voice is represented, but unfortunately through federal voter suppression and gerrymandering, that hasn’t been the case. -

Presented by the Washington Dc Jewish Community Center's Morris

Presented by the Washington dC JeWish Community Center’s morris Cafritz Center for the arts · Co-Sponsored by the embassy of israel and Washington JeWish Week sunday monday tuesday Aaron & Cecile Goldman Theater AFI Silver Theatre Aaron & Cecile Goldman Theater Aaron & Cecile Goldman Theater Love and Religion: The Challenge Will Eisner: Portrait Human Failure In Search of the Bene Israel of Interfaith Relationships of a Sequential Artist E 6:00 pm and Rafting to Bombay E 10:30 am brunch, 11:30 am film E 12:15 pm Srugim E 6:15 pm The Worst Company in the World Broken Promise E 8:30 pm Shorts Program 1 with Quentin and Ferdinand E 5:45 pm Take Five: Queer Shorts, E 1:45 pm Ajami AFI Silver Theatre Good Stories 2009 WJFF Visionary Award E 8:15 pm The Girl on the Train E 8:30 pm Honoring Michael Verhoeven E 7:00 pm Screening of Nasty Girl Embassy of Ethiopia Mary and Max Goethe-Institut Washington E 3:30 pm The Name My Mother Gave Me E 9:00 pm From Swastika to Jim Crow E Noon Filmed by Yitzhak and Black Over White E Goethe-Institut Washington and The Green Dumpster Mystery 2:00 pm In Conversation Embassy of Switzerland E 6:15 pm with Michael Verhoeven Brothers Lost Islands E Noon E 7:00 pm E 8:30 pm Harold and Sylvia Greenberg Theatre Lost Islands 6 7 E 7:30 pm 8 sunday Aaron & Cecile Goldman Theater Avalon Theatre The Earth Cries Out The Jester E 11:30 am E 11:30 am FREE Room and a Half 18 KM E 1:45 pm with The Red Toy The Wedding Song E 2:00 pm E 5:00 pm Heart of Stone E 4:00 pm The Gift to Stalin CLOSING NIGHT FILM AND PARTY E 7:30 pm 13 thursday friday saturday Embassy of France Aaron & Cecile Goldman Theater Aaron & Cecile Goldman Theater A Matter of Size A Matter of Size My Mother’s Courage OPENING NIGHT FILM AND Party E 1:00 pm with The Legend of Mrs. -

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections David Hirsh Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series, Charles Asher Small. Working Paper Hirsh 2007 ISSN: 1940-610X © Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, Second floor New York, NY 10022 United States Office Telephone: 212-230-1840 www.isgap.org ABSTRACT This paper aims to disentangle the difficult relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. On one side, antisemitism appears as a pressing contemporary problem, intimately connected to an intensification of hostility to Israel. Opposing accounts downplay the fact of antisemitism and tend to treat the charge as an instrumental attempt to de-legitimize criticism of Israel. I address the central relationship both conceptually and through a number of empirical case studies which lie in the disputed territory between criticism and demonization. The paper focuses on current debates in the British public sphere and in particular on the campaign to boycott Israeli academia. Sociologically the paper seeks to develop a cosmopolitan framework to confront the methodological nationalism of both Zionism and anti-Zionism. It does not assume that exaggerated hostility to Israel is caused by underlying antisemitism but it explores the possibility that antisemitism may be an effect even of some antiracist forms of anti- Zionism. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 165 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 13, 2019 No. 45 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was Comer, where he was one of seven sib- have been positively affected by the called to order by the Speaker pro tem- lings. He was born in Rock Hill, South giving and donations to Christian pore (Mr. SOTO). Carolina, where he attended Oak Ridge causes, such as the men’s shelters and f Elementary School and later served in the Boys and Girls Clubs, will be re- the United States Merchant Marines. membered for years to come. DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO He was married to Francis Watkins The company is now being run by his TEMPORE Comer for 64 years and had two chil- son, Chip Comer, and the legacy of his The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- dren, Brenda Comer Sutton and Leon father can be summed up by the words fore the House the following commu- ‘‘Chip’’ Comer, Jr. of Chip when he said the following: nication from the Speaker: Leon Comer believed in the value of ‘‘My father is the epitome of what I WASHINGTON, DC, hard work and, after working as a man- would always want to be, as he taught March 13, 2019. ager of a beer distributor in the greater me so many life lessons growing up.’’ I hereby appoint the Honorable DARREN Rock Hill market for 12 years, he Leon Comer left an indelible imprint SOTO to act as Speaker pro tempore on this founded Comer Distributing in 1971, on the many lives that he touched, and day. -

Library of Congress Magazine January/February 2018

INSIDE PLUS A Journey Be Mine, Valentine To Freedom Happy 200th, Mr. Douglass Find Your Roots Voices of Slavery At the Library LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2018 Building Black History A New View of Tubman LOC.GOV LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE Library of Congress Magazine Vol. 7 No. 1: January/February 2018 Mission of the Library of Congress The Library’s central mission is to provide Congress, the federal government and the American people with a rich, diverse and enduring source of knowledge that can be relied upon to inform, inspire and engage them, and support their intellectual and creative endeavors. Library of Congress Magazine is issued bimonthly by the Office of Communications of the Library of Congress and distributed free of charge to publicly supported libraries and research institutions, donors, academic libraries, learned societies and allied organizations in the United States. Research institutions and educational organizations in other countries may arrange to receive Library of Congress Magazine on an exchange basis by applying in writing to the Library’s Director for Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access, 101 Independence Ave. S.E., Washington DC 20540-4100. LCM is also available on the web at loc.gov/lcm/. All other correspondence should be addressed to the Office of Communications, Library of Congress, 101 Independence Ave. S.E., Washington DC 20540-1610. [email protected] loc.gov/lcm ISSN 2169-0855 (print) ISSN 2169-0863 (online) Carla D. Hayden Librarian of Congress Gayle Osterberg Executive Editor Mark Hartsell Editor John H. Sayers Managing Editor Ashley Jones Designer Shawn Miller Photo Editor Contributors Bryonna Head Wendi A. -

The End of Uncle Tom

1 THE END OF UNCLE TOM A woman, her body ripped vertically in half, introduces The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven from 1995 (figs.3 and 4), while a visual narra- tive with both life and death at stake undulates beyond the accusatory gesture of her pointed finger. An adult man raises his hands to the sky, begging for deliverance, and delivers a baby. A second man, obese and legless, stabs one child with his sword while joined at the pelvis with another. A trio of children play a dangerous game that involves a hatchet, a chopping block, a sharp stick, and a bucket. One child has left the group and is making her way, with rhythmic defecation, toward three adult women who are naked to the waist and nursing each other. A baby girl falls from the lap of one woman while reaching for her breast. With its references to scatology, infanticide, sodomy, pedophilia, and child neglect, this tableau is a troubling tribute to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin—the sentimental, antislavery novel written in 1852. It is clearly not a straightfor- ward illustration, yet the title and explicit references to racialized and sexualized violence on an antebellum plantation leave little doubt that there is a significant relationship between the two works. Cut from black paper and adhered to white gallery walls, this scene is composed of figures set within a landscape and depicted in silhouette. The medium is particularly apt for this work, and for Walker’s project more broadly, for a number of reasons. -

Viewer's Guide

SELMA T H E BRIDGE T O T H E BALLOT TEACHING TOLERANCE A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER VIEWER’S GUIDE GRADES 6-12 Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is the story of a courageous group of Alabama students and teachers who, along with other activists, fought a nonviolent battle to win voting rights for African Americans in the South. Standing in their way: a century of Jim Crow, a resistant and segregationist state, and a federal govern- ment slow to fully embrace equality. By organizing and marching bravely in the face of intimidation, violence, arrest and even murder, these change-makers achieved one of the most significant victories of the civil rights era. The 40-minute film is recommended for students in grades 6 to 12. The Viewer’s Guide supports classroom viewing of Selma with background information, discussion questions and lessons. In Do Something!, a culminating activity, students are encouraged to get involved locally to promote voting and voter registration. For more information and updates, visit tolerance.org/selma-bridge-to-ballot. Send feedback and ideas to [email protected]. Contents How to Use This Guide 4 Part One About the Film and the Selma-to-Montgomery March 6 Part Two Preparing to Teach with Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot 16 Part Three Before Viewing 18 Part Four During Viewing 22 Part Five After Viewing 32 Part Six Do Something! 37 Part Seven Additional Resources 41 Part Eight Answer Keys 45 Acknowledgements 57 teaching tolerance tolerance.org How to Use This Guide Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is a versatile film that can be used in a variety of courses to spark conversations about civil rights, activism, the proper use of government power and the role of the citizen. -

New LAPD Chief Shares His Policing Vision with South L.A. Black Leaders

Abess Makki Aims to Mitigate The Overcomer – Dr. Bill Water Crises First in Detroit, Then Releford Conquers Major Setback Around the World to Achieve Professional Success (See page A-3) (See page C-1) VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBERSEPTEMBER 12 17,- 18, 2015 2013 VOL. LXXXV NO 25 $1.00 +CA. Sales Tax“For Over “For Eighty Over EightyYears TheYears Voice The ofVoice Our of Community Our Community Speaking Speaking for Itselffor Itself” THURSDAY, JUNE 21, 2018 The event was a 'thank you card' to the Los Angeles community for a rich history of support and growth together. The organization will continue to celebrate its 50th milestone throughout the year. SPECIAL TO THE SENTINEL Proclamations and reso- lutions were awarded to the The Brotherhood Cru- organization, including a sade, is a community orga- U.S. Congressional Records nization founded in 1968 Resolution from the 115th by civil rights activist Wal- Congress (House of Repre- ter Bremond. For 35 years, sentatives) Second Session businessman, publisher and by Congresswoman Karen civil rights activist Danny J. Bass, 37th Congressional Bakewell, Sr. led the Institu- District of California. tion and last week, Brother- Distinguished guests hood Crusade president and who attended the event in- CEO Charisse Bremond cluded: Weaver hosted a 50th Anni- CA State Senator Holly versary Community Thank Mitchell; You Event on Friday, June CA State Senator Steve 15, 2018 at the California CA State Assemblymember Science Center in Exposi- Reggie Jones-Sawyer; tion Park. civil rights advocate and The event was designed activist Danny J. -

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave How to analyze slave narratives. Who Was Solomon Northup? 1808: Born in Minerva, NewYork Son of former slave, Mintus Northup; Northup's mother is unknown. 1829: Married Anne Hampton, a free black woman. They had three children. Solomon was a farmer, a rafter on the Lake Champlain Canal, and a popular local fiddler. What Happened to Solomon Northup? Met two circus performers who said they needed a fiddler for engagements inWashington, D.C. Traveled south with the two men. Didn't tell his wife where he was going (she was out of town); he expected to be back by the time his family returned. Poisoned by the two men during an evening of social drinking inWashington, D.C. Became ill; he was taken to his room where the two men robbed him and took his free papers; he vaguely remembered the transfer from the hotel but passed out. What Happened…? • Awoke in chains in a "slave pen" in Washington, D.C., owned by infamous slave dealer, James Birch. (Note: A slave pen were where (Note:a slave pen was where slaves were warehoused before being transported to market) • Transported by sea with other slaves to the New Orleans slave market. • Sold first toWilliam Prince Ford, a cotton plantation owner. • Ford treated Northup with respect due to Northup's many skills, business acumen and initiative. • After six months Ford, needing money, sold Northup to Edwin Epps. Life on the Plantation Edwin Epps was Northup’s master for eight of his 12 years a slave. -

Contemporary Left Antisemitism

“David Hirsh is one of our bravest and most thoughtful scholar-activ- ists. In this excellent book of contemporary history and political argu- ment, he makes an unanswerable case for anti-anti-Semitism.” —Anthony Julius, Professor of Law and the Arts, UCL, and author of Trials of the Diaspora (OUP, 2010) “For more than a decade, David Hirsh has campaigned courageously against the all-too-prevalent demonisation of Israel as the one national- ism in the world that must not only be criticised but ruled altogether illegitimate. This intellectual disgrace arouses not only his indignation but his commitment to gather evidence and to reason about it with care. What he asks of his readers is an equal commitment to plumb how it has happened that, in a world full of criminality and massacre, it is obsessed with the fundamental wrongheadedness of one and only national movement: Zionism.” —Todd Gitlin, Professor of Journalism and Sociology, Columbia University, USA “David Hirsh writes as a sociologist, but much of the material in his fascinating book will be of great interest to people in other disciplines as well, including political philosophers. Having participated in quite a few of the events and debates which he recounts, Hirsh has done a commendable service by deftly highlighting an ugly vein of bigotry that disfigures some substantial portions of the political left in the UK and beyond.” —Matthew H. Kramer FBA, Professor of Legal & Political Philosophy, Cambridge University, UK “A fierce and brilliant rebuttal of one of the Left’s most pertinacious obsessions. What makes David Hirsh the perfect analyst of this disorder is his first-hand knowledge of the ideologies and dogmata that sustain it.” —Howard Jacobson, Novelist and Visiting Professor at New College of Humanities, London, UK “David Hirsh’s new book Contemporary Left Anti-Semitism is an impor- tant contribution to the literature on the longest hatred. -

Plaintiff's Reply

Case 1:07-cv-02067-NGG-RLM Document 174 Filed 06/25/2008 Page 1 of 38 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ---------------------------------------------------------------------X UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff, -and- THE VULCAN SOCIETY, INC., ET AL, Civ. Action No. 07-CV-2067 (NGG)(RLM) Plaintiffs-Intervenors, ECF Case -against- Served June 25, 2008 THE CITY OF NEW YORK, ET AL, Defendants. ---------------------------------------------------------------------X MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN FURTHER SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-INTERVENORS’ MOTION FOR THE CERTIFICATION OF A CLASS AND IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-INTERVENORS’ MOTION TO AMEND AND SUPPLEMENT THE COMPLAINT SCOTT + SCOTT, LLP LEVY RATNER, P.C. 29 West 57th Street 80 Eighth Avenue, 8th Floor New York, NY 10019 New York, NY 10011 (212) 223-6444 (212) 627-8100 (212) 223-6334 (fax) (212) 627-8182 (fax) CENTER FOR Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Intervenors CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS 666 Broadway, 7th Floor New York, NY 10012-2399 (212) 614-6438 (212) 614-6499 (fax) On the brief: Richard A. Levy Dana Lossia Judy Scolnick Darius Charney 56-001-00001 15512.DOC Case 1:07-cv-02067-NGG-RLM Document 174 Filed 06/25/2008 Page 2 of 38 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................................................................................1 POINT I. Unlawful Employment Practices Uncovered During the Course of Discovery Are Properly Adjudicated In This Case ................................................2 A. The Employment Practices Being Challenged..................................................................2 B. The Challenged Practices Were Part of The EEOC Charges, And Have Been The Subject of Discovery In This Case...................................................5 C. The Challenge to Exam 6019 Should Be Included In This Action And Those Injured by Exam 6019 Are Proper Members of the Proposed Class..............10 POINT II. -

Uncle Tom's Cabin: Its History, Its Issues, and Its Consequences

Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Its History, Its Issues, and Its Consequences Abstract: This research paper analyzes Harriet Beecher Stowe’s most influential and successful work, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Although Uncle Tom’s Cabin began as a simple novel written by a woman who was both a wife and mother, it grew to be one of the strongest antislavery books and was even credited with giving the impetus to initiate the Civil War. Stowe incorporated several strongly debated issues of her time in the novel, including slavery, alcohol temperance, and gender roles. However, she was careful to work within the accepted social boundaries and was thus able to appeal to many groups through her novel. Nevertheless, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was highly controversial and sparked a storm of discussion and action from the entire world. This paper explores Stowe’s life, the issues contained within the novel and their presentation, and the reactions of the American public and the world. Course: American Literature I, ENGL 2310 Semester/Year: FA/2012 Instructor: Deborah S. Koelling 1 Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Its History, Its Issues, and Its Consequences When she wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe had no idea that she was unleashing a literary giant on the world. Stowe herself was a good wife and mother, and her accomplishment is astonishing for both its near-radical ideas and for its traditional presentation,. Some of the strength of the novel is drawn from Stowe’s own life experiences and struggles, further intensifying the message of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In fact, Abraham Lincoln is quoted as saying, “so this is little woman who caused the great war!” (in reference to the Civil War, qtd.