Initiatives Supporting Evidence Informed Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discussion Piece Reflecting on the Recent Implementation of Programmes and Policies Supported by the World Bank in Benin, Camero

COMMUNITY-BASED RESULTS-BASED FINANCING IN HEALTH IN PRACTICE. A discussion piece reflecting on the recent implementation of programmes and policies supported by the World Bank in Benin, Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, The Gambia, and Rwanda Jean-Benoît Falisse, Petra Vergeer, Maud Juquois, Alphonse Akpamoli, Jacob Paul Robyn, Walters Shu, Michel Zabiti, Rifat Hasan, Bakary Jallow, Musa Loum, Cédric Ndizeye, Michel Muvudi, Baudouin Makuma Booto Joy Gebre Medhin Executive summary This report discusses Community Results-Based Financing (cRBF), a 'close to client' approach whereby community actors are paid based on the activities they undertake. The focus is on six developing cRBF experiences that have started in Cameroon, The Gambia, Benin, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo), Rwanda, and the Republic of Congo. The report's main aim is to cast light on the success and difficulties encountered in the implementation of such a programme. The report is based on a participative process that included a short review of the existing literature on cRBF, a review of the manuals of procedures and reports produced in each country case, in-depth interviews with a focal point in five countries, and two workshops with practitioners. Do cRBF schemes work? It is too early to say: most schemes are still in their infancy. An impact evaluation of the Rwandan scheme found mixed effects. The Cameroon, Congo, and the Gambia schemes integrate rigorous impact evaluation mechanisms and the first results should be available in two to five years. At this stage, the main discussion is on the implementation of cRBF. -

WHO in Cameroon

Summary : Pages List of abbreviations 3 Editorial 5 7 Highlights of 2016 6 Significant quotes in 2016 8 Figures , charts and tables 9 Introduction 10 1. Communicable Diseases 12 1.1. HIV / AIDS 1.2. TUBERCULOSIS 14 1.3. MALARIA 1.4. NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES 15 1.5. VACCINE PREVENTABLE DISEASES 19 6 2. Noncommunicable Diseases 24 2.1. NONCOMMUNICABLE DISEASES 2.2. NUTRITION 25 3. Promoting health at all stages of life 25 3.1. REPRODUCTIVE, MATERNAL, NEWBORN, CHILD AND ADOLESCENT HEALTH. 4. Health Systems 31 4.1. NATIONAL HEALTH POLICIES, STRATEGIES AND PLANS 4.2. ACCESS TO DRUGS AND HEALTH TECHNOLOGIES, AND STRENGTHENING REGULATORY MEASURES 4.3. INFORMATION AND DATA ON HEALTH SYSTEMS 32 5. Preparedness, monitoring and response 33 5.1. ALERT AND INTERVENTION CAPACITIES 5.2. MANAGEMENT OF CRISES AND RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH EMERGENCIES 35 5.3. POLIOMYELITIS ERADICATION 36 6. Institutional and Support Services 42 6.1. PROGRAMME SUPPORT (COUNTRY SUPPORT UNIT) 6.2. HUMAN RESOURCES 43 6.3. FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT AND INTERNAL CONTROL 6.4. IMPROVEMENT OF THE WORKING ENVIRONMENT 45 6.5. INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES 14 6.6. COMMUNICATION SUPPORT PROGRAMMES 46 >> The faces of the office 47 - 50 ANNEX 51 Acknowledgements Annex 1 : Obstacles and constraints 52 Throughout the year, we worked with the Lessons learned Ministry of Public Health, the Government Prospects for the year 2017 53 of Cameroon, numerous bilateral and Annex 2 : Support received from IST – AFRO - HQ 54 multilateral partners, governmental orga - nizations and the civil society. Annex 3 : Assistance Missions to the Country We therefore express to them our deepest Annex 4 : List of documents produced 55 appreciation. -

Banking on Health: World Bank and African Development Bank Spending on Reproductive Health And

Banking on Health: World Bank and African Development Bank Spending on Reproductive Health and HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa i Publication prepared by: Claire Lauterbach, Programs Associate, Gender Action With contributions from: Elaine Zuckerman, President, Gender Action Elizabeth Arend, former Programs Coordinator, Gender Action Patience Nyangoma, Executive Director, NAWAD Christian Tanyi, Chief Executive Officer, LUKMEF With support from: The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation The Tides Foundation Copyright © Gender Action 2012 About Gender Action Gender Action was established in 2002. It is the only organization dedicated to promoting gender justice and women’s rights in all International Financial Institution (IFI) investments such as those of the World Bank. Gender Action’s goal is to ensure that women and men equally participate in and benefit from all IFI investments. Gender Action 1875 Connecticut Avenue NW Suite 500 Washington DC 20009, USA Tel: 202 939 5463 Email: [email protected] http://www.genderaction.org ii Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................... iv Executive Summary....................................................................................................................................... v Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................1 Population and reproductive -

Health Care System and Health Financing Structure, the Case of Cameroon

IAAOJ, Health Science, 2013,1(2), 24-44 HEALTH CARE SYSTEM AND HEALTH FINANCING STRUCTURE, THE CASE OF CAMEROON Hayriye IŞIK1, Hubert NDIFUSAH2 1 NKU FEAS Department of Public Finance 2 NKU Institute of Social Science Department of Health Care Management ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to identify healthcare systems and its financial components of Cameroon. As we know, Health care financing studies in Africa and cross-national levels have tended to focus on many modes of financing at a time, such as user fees, insurance,government budget, external aid, also on financing-related issues such as equity and quality of care. Relatively few attempts have been made in the literature to analyze total national health financing from all sources and to relate them to their various uses. This study also uses the broader framework of National Health Accounts (NHA) to analyze national health system and financing in Cameroon. Health care financing is one of the fastest growing areas in the field of public health economics. Health systems are defined as comprising all the organizations, institutions and resources that are devoted to producing health activities. Due to that reasons this study examined the challenges of health system and financing health care in Cameroon. It also identified various funding mechanisms available to finance health care in Cameroon. Key Words: Healthcare System, financing, funding mechanisms and Cameroon Isık and et al. ÖZET Bu çalışmanın amacı Kamerun sağlık sisteminin ve sistemin finansal bileşenlerini tanımlamaktır. Bildiğimiz gibi, Afrika ve uluslar arası düzeyde sağlık hizmet finansmanı çalışmalarında tüketici ödemeleri, sigorta, kamu bütçe kaynakları, dış yardımlar gibi çeşitli yöntem eğilimlerinin yanı sıra hizmet etkinliği ve kalitesi gibi finansmanla alakalı konular vardır. -

WEEKLY BULLETIN on OUTBREAKS and OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 12: 16 - 22 March 2020 Data As Reported By: 17:00; 22 March 2020

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 12: 16 - 22 March 2020 Data as reported by: 17:00; 22 March 2020 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 7 95 91 11 New events Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 201 17 Algeria 1 0 91 0 2 0 Gambia 1 0 1 0 Mauritania 14 7 20 0 9 0 Senegal 304 1 1 0Eritrea Niger 2 410 23 Mali 67 0 1 0 3 0 Burkina Faso 41 7 1 0 Cabo Verdé Guinea Chad 1 251 0 75 3 53 0 4 0 4 690 18 4 1 22 0 21 0 Nigeria 2 0 Côte d’Ivoire 1 873 895 15 4 0 South Sudan 917 172 40 0 3 970 64 Ghana16 0 139 0 186 3 1 0 14 0 Liberia 25 0 Central African Benin Cameroon 19 0 4 732 26 Ethiopia 24 0 Republic Togo 1 618 5 7 626 83 352 14 1 449 71 2 1 Uganda 36 16 Democratic Republic 637 1 169 0 9 0 15 0 Equatorial of Congo 15 5 202 0 Congo 1 0 Guinea 6 0 3 453 2 273 Kenya 1 0 253 1 Legend 3 0 6 0 38 0 37 0 Gabon 29 981 384 Rwanda 21 0 Measles Humanitarian crisis 2 0 4 0 4 998 63 Burundi 7 0 Hepatitis E 8 0 Monkeypox 8 892 300 3 294 Seychelles 30 2 108 0 Tanzania Yellow fever 12 0 Lassa fever 79 0 Dengue fever Cholera Angola 547 14 Ebola virus disease Rift Valley Fever Comoros 129 0 2 0 Chikungunya Malawi 218 0 cVDPV2 2 0 Zambia Leishmaniasis Mozambique 3 0 3 0 COVID-19 Plague Zimbabwe 313 13 Madagascar Anthrax Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever Namibia 286 1 Malaria 2 0 24 2 12 0 Floods Meningitis 3 0 Mauritius Cases 7 063 59 1 0 Deaths Countries reported in the document Non WHO African Region Eswatini N WHO Member States with no reported events W E 3 0 Lesotho4 0 402 0 South Africa 20 0 S South Africa Graded events † 40 15 1 Grade 3 events Grade 2 events Grade 1 events 39 22 20 31 Ungraded events ProtractedProtracted 3 3 events events Protracted 2 events ProtractedProtracted 1 1 events event Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview This Weekly Bulletin focuses on public health emergencies occurring in the WHO Contents African Region. -

The Health Workers Crises in Cameroon

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Public Health Theses School of Public Health Summer 8-6-2010 The Health Workers Crises In Cameroon Adidja Amani Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/iph_theses Part of the Public Health Commons Recommended Citation Amani, Adidja, "The Health Workers Crises In Cameroon." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2010. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/iph_theses/139 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Public Health at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Health Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Institute of Public Health Public Health Theses Georgia State University, Year 2010 The Health Workers Crises In Cameroon Adidja Amani Georgia State University, [email protected] ABSTRACT The physician‘s crisis in Cameroon has reached an alarming stage and has the potential to worsen existing health problems including the attainment of millennium development goals. This report emphasized the challenges faced by Cameroonian physicians, and recommended alternative solutions to the current government health workers policies. The report was done through a review of articles and documents covering the topic. At the center of the physician‘s crises in Cameroon is the discrepancy between financial, social and professional expectations and what the government offers. The analysis showed that, there is a general dissatisfaction, despite some corrective measures implemented by the government. This suggests that the government needs to aggressively adopt and implement aggressive retention policies, such as improving the remuneration and working conditions of health workers. -

Report for Cameroon

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized CAMEROON ECONOMIC UPDATE Towards Greater Equity A Special Focus on Health July 2013 © 2013 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. Note that The World Bank does not necessarily own each component of the content included in the work. The World Bank therefore does not warrant that the use of the content contained in the work will not infringe on the rights of third parties. The risk of claims resulting from such infringement rests solely with you. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the Governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Photo credits: © Raju Singh/World Bank - Cover: Middle photo © Edmond Bagde Dingamhoudou/World Bank - Cover: Left & Right photos; pages vii, 1 & 25. -

Mobile Health Teams, Decolonization, and the Eradication Era in Cameroon, 1945-1970 Sarah Cook Runcie

Mobile Health Teams, Decolonization, and the Eradication Era in Cameroon, 1945-1970 Sarah Cook Runcie Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2017 © 2017 Sarah Cook Runcie All rights reserved Abstract Mobile Health Teams, Decolonization, and the Eradication Era in Cameroon, 1945-1970 Sarah Cook Runcie This dissertation examines the intersecting changes of African decolonization and the post-World War II internationalization of public health by showing how Cameroonian and French health officials shaped global health programs on the ground in the 1950s and 60s. I approach this topic through the lens of two tightly interwoven developments in Cameroon: the history of colonial mobile health teams created by French military doctors and the advent of postwar global disease eradication campaigns. While colonial medicine and international health are typically treated as distinct historical subjects, I argue that global disease eradication programs in this period in Cameroon relied entirely on colonial mobile health teams and their reformulation after independence as a basis of infrastructure, personnel and knowledge. I specifically assert that Cameroonian and French health officials positioned mobile health teams as cornerstones of national health policy and regional health coordination in Central Africa and, in turn, as the basis for operations of attempted global disease eradication programs within Cameroon. As Cameroonian, French and international health officials negotiated the work of the mobile health teams through decolonization and the first decade of the independence, they were moreover charting new structures of authority and control over medicine and public health between the global and the local, and forging an international politics of public health rooted in the particular tensions of decolonization in the country. -

WEEKLY BULLETIN on OUTBREAKS and OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 3: 13 - 19 January 2020 Data As Reported By: 17:00; 19 January 2020

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 3: 13 - 19 January 2020 Data as reported by: 17:00; 19 January 2020 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 67 53 15 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 1 215 0 20 0 2 0 10 207 55 Senegal Mali Niger 26 623 259 1 0 41 7 1 251 0 336 7 Guinea Burkina Faso 52 0 Chad 4 690 18 26 2 2 089 21 Côte d’Ivoire Nigeria Sierra léone 9 0 895 15 South Sudan Ethiopia 812 181 137 2 9 672 7 4 Ghana 3 787 192 Cameroon Central African 5 0 Liberia 4 414 23 Benin Republic 16 0 54 908 0 58 916 289 1 307 55 2 904 49 Togo 1 170 14 2 1 Democratic Republic Uganda 79 20 1 692 5 3 0 1 0 510 1 of Congo 5 150 39 78 13 Congo 3 412 2 237 2 2 Kenya Legend 6 0 2 879 34 316 550 6 102 Measles Humanitarian crisis 11 434 0 29 087 501 Burundi Hepatitis E 8 724 857 3 233 Monkeypox 84 0 1 064 6 Yellow fever Lassa fever 51 8 Dengue fever Cholera Angola 5 117 104 Ebola virus disease Rift Valley Fever Comoros 71 0 2 0 Chikungunya 218 0 cVDPV2 Zambia Leishmaniasis Malaria Floods Plague Cases Meningitis Namibia Deaths Countries reported in the document Non WHO African Region 6 974 59 WHO Member States with no reported events N W E 3 0 Lesotho 59 0 South Africa 20 0 S Graded events † 3 14 1 Grade 3 events Grade 2 events Grade 1 events 43 22 20 31 Ungraded events PB ProtractedProtracted 3 3 events events Protracted 2 events ProtractedProtracted 1 1 events event 1 Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview This Weekly Bulletin focuses on public health emergencies occurring in the WHO Contents African Region. -

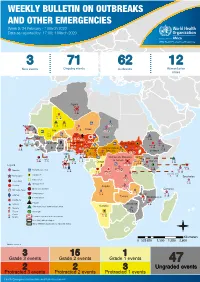

WEEKLY BULLETIN on OUTBREAKS and OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 9: 24 February - 1 March 2020 Data As Reported By: 17:00; 1 March 2020

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 9: 24 February - 1 March 2020 Data as reported by: 17:00; 1 March 2020 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 3 71 62 12 New events Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises Algeria 3 0 91 0 14 7 20 0 3 0 Senegal 304 1 Niger 2 410 23 1 0 1 0 Mali 41 7 336 7 Guinea Burkina Faso 53 0 Chad 1 251 0 1 0 4 690 18 26 2 Nigeria Côte d’Ivoire 1 873 Sierra léone 18 0 895 15 South Sudan 698 127 3 970 64 139 0 167 2 7 4 Central African 12 0 Liberia Ghana Cameroon Benin Republic 19 0 4 732 26 Ethiopia 1 618 5 1 449 71 7 626 83 Togo 1 170 14 2 1 Democratic Republic Uganda 31 14 169 0 9 0 1 0 of Congo 1 0 83 13 Congo 15 5 Kenya 3 444 2 264 2 2 253 1 Legend 4 1 38 0 202 0 20 475 252 Measles Humanitarian crisis 8 0 637 1 37 0 3 575 52 Burundi Hepatitis E 8 892 300 3 294 Monkeypox Seychelles 105 0 Yellow fever Lassa fever 79 0 Dengue fever Cholera Angola 378 8 Ebola virus disease Rift Valley Fever Comoros 117 0 2 0 Chikungunya Malawi 218 0 cVDPV2 Zambia Leishmaniasis Mozambique 3 0 COVID-19 Plague 313 13 Anthrax Zimbabwe Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever Namibia Malaria 286 1 Floods Meningitis Cases 7 063 59 Deaths Countries reported in the document Non WHO African Region N WHO Member States with no reported events W E 3 0 Lesotho South Africa 20 0 S Graded events † 3 15 1 Grade 3 events Grade 2 events Grade 1 events 47 22 20 31 Ungraded events ProtractedProtracted 3 3 events events Protracted 2 events ProtractedProtracted 1 1 events event Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview This Weekly Bulletin focuses on public health emergencies occurring in the WHO Contents African Region. -

Perceptions of Access to Healthcare in Cameroon by Women of Childbearing Age Wenceslaw Chap Chapnkem Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2019 Perceptions of Access to Healthcare in Cameroon by Women of Childbearing Age Wenceslaw Chap Chapnkem Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Health and Medical Administration Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Health Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Wenceslaw C. Chapnkem has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Jeanne Connors, Committee Chairperson, Health Services Faculty Dr. Magdeline Aagard, Committee Member, Health Services Faculty Dr. Sriya Krishnamoorthy, University Reviewer, Health Services Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2019 Abstract Perceptions of Access to Healthcare in Cameroon by Women of Childbearing Age By Wenceslaw C. Chapnkem MA, Strayer University, 2006 BS, University of Buea, 1998 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Health Services Administration Walden University August 2019 Abstract Increased poverty and unemployment rates, minimal investment in social amenities, a shortage of healthcare professionals, poor infrastructure, inadequate social services, and poor institutional and political leadership have weakened the healthcare status of Cameroon’s women who have reached the age of childbearing. -

Health Results Innovation Trust Fund Mid Term Review Final Report

Health Results Innovation Trust Fund Mid Term Review Final Report Prepared for // IOD PARC is the trading name of International Jo Keatinge, Meena Gandhi, Organisation Development Ltd// DFID, Ingvar Olsen, Norad, Monique Vledder, World Bank Omega Court 362 Cemetery Road Date // 4 April 2018 Sheffield S11 8FT By// Emma Henrion, Annalize United Kingdom Struwig, Enrique Wedgwood Young, Madeleine Guay, Tel: +44 (0) 114 267 3620 Christiane Duering www.iodparc.com i Contents Acknowledgements iii Acronyms iv Executive Summary 6 Evaluation results 7 The Health Results Innovation Trust Fund 13 The Global Financing Facility 18 Purpose of the evaluation and methodology 20 Objectives 20 Methodology 20 Limitations to the evaluation 21 Findings 23 Relevance 23 Effectiveness 27 Efficiency 37 Impact 45 Equity 55 Sustainability 58 Review of progress on recommendations from the 2012 HRITF Evaluation 62 Conclusions 67 Recommendations 71 Learning for future RBF programmes 72 Annex 1: Terms of Reference I Annex 2: Evaluation framework and questions I Annex 3: Summary of HRITF country grants VI Annex 4 HRITF Results Framework XIII Annex 5: Global stakeholders interviewed XVI i Annex 6: HRITF Country Pilot Grants Projections, Actuals and Disbursements between 2010 and 2019 for case study countries XVII Annex 7: HRITF Disbursements Summary by Activity Category US$ Million XX Annex 8: Summary of completed impact evaluations XXI Annex 9: Deep Dive case studies summaries XXIII Nigeria Case Study XXIII Zimbabwe Case Study XXVI Cameroon case study XXVII Annex 10: References and documents reviewed XXXV ii Acknowledgements Many thanks are due to many people for their help and contributions to this report.