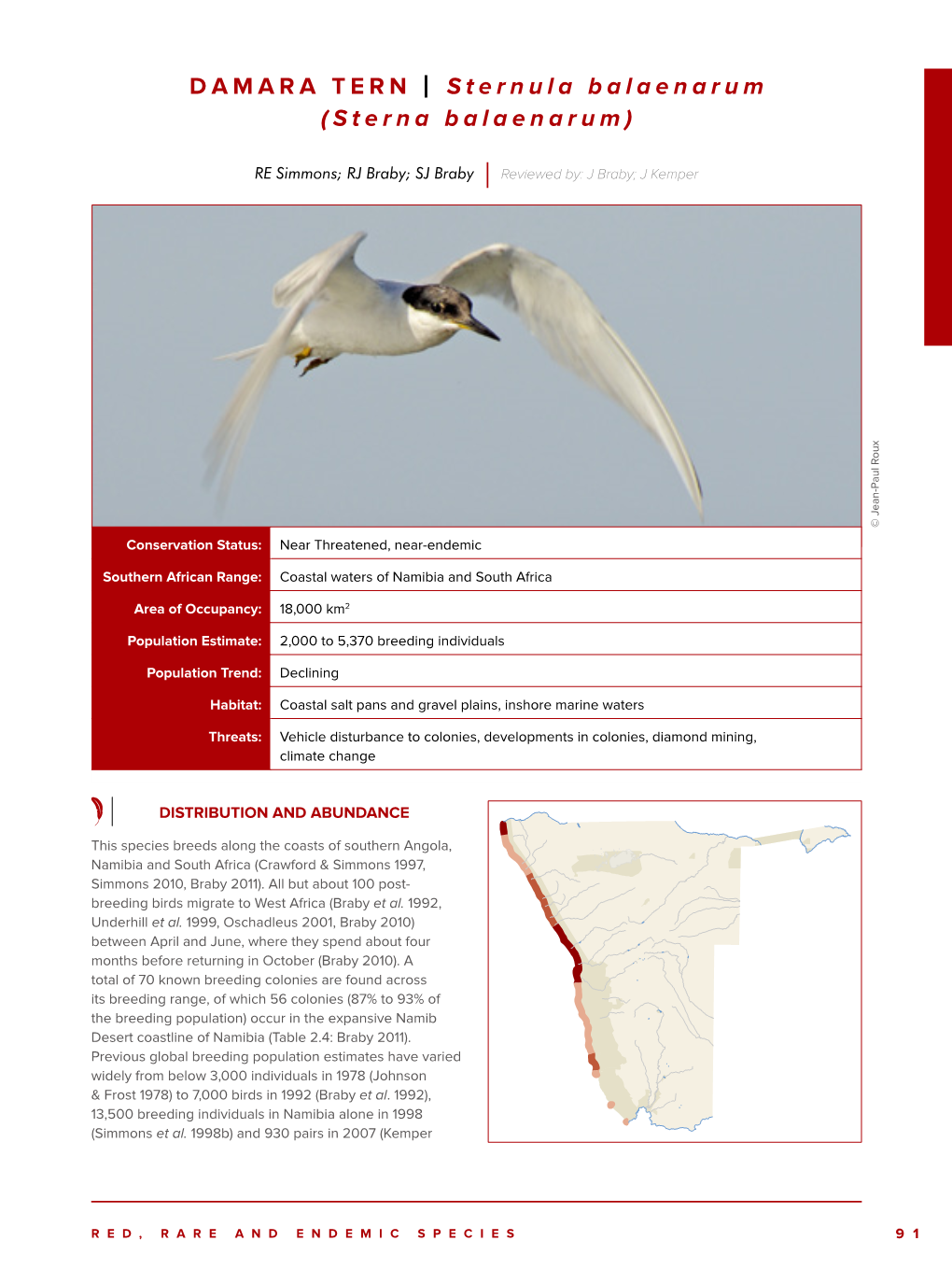

DAMARA TERN | Sternula Balaenarum (Sterna Balaenarum)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Monitoring Program for Biodiversity and Non-Indigenous Species in Egypt

UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAM MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN REGIONAL ACTIVITY CENTRE FOR SPECIALLY PROTECTED AREAS National monitoring program for biodiversity and non-indigenous species in Egypt PROF. MOUSTAFA M. FOUDA April 2017 1 Study required and financed by: Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas Boulevard du Leader Yasser Arafat BP 337 1080 Tunis Cedex – Tunisie Responsible of the study: Mehdi Aissi, EcApMEDII Programme officer In charge of the study: Prof. Moustafa M. Fouda Mr. Mohamed Said Abdelwarith Mr. Mahmoud Fawzy Kamel Ministry of Environment, Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) With the participation of: Name, qualification and original institution of all the participants in the study (field mission or participation of national institutions) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS page Acknowledgements 4 Preamble 5 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: Institutional and regulatory aspects 40 Chapter 3: Scientific Aspects 49 Chapter 4: Development of monitoring program 59 Chapter 5: Existing Monitoring Program in Egypt 91 1. Monitoring program for habitat mapping 103 2. Marine MAMMALS monitoring program 109 3. Marine Turtles Monitoring Program 115 4. Monitoring Program for Seabirds 118 5. Non-Indigenous Species Monitoring Program 123 Chapter 6: Implementation / Operational Plan 131 Selected References 133 Annexes 143 3 AKNOWLEGEMENTS We would like to thank RAC/ SPA and EU for providing financial and technical assistances to prepare this monitoring programme. The preparation of this programme was the result of several contacts and interviews with many stakeholders from Government, research institutions, NGOs and fishermen. The author would like to express thanks to all for their support. In addition; we would like to acknowledge all participants who attended the workshop and represented the following institutions: 1. -

LEAST TERN Scientific Name: Sternula Antillarum Lesson Other

Common Name: LEAST TERN Scientific Name: Sternula antillarum Lesson Other Commonly Used Names: Little tern, silver turnlet, sea swallow, minute tern, little striker, and killing peter Previously Used Names: Sterna antillarum Family: Laridae Rarity Ranks: G4/S3 State Legal Status: Rare Federal Legal Status: Interior population listed as endangered. Other populations are not federally listed. Federal Wetland Status: N/A Description: Georgia's smallest tern at about 23 cm (9 in) in length with a 50 cm (20 in) wingspread, the least tern is white with pale gray feathers on the back and upper surfaces of the wings, except for a narrow black stripe along the leading edge of the upper wing feathers. The least tern has a black cap with a small patch of white on the forehead. In summer, the adult has a yellow bill with a black tip and yellow to orange feet and legs. Its tail is deeply forked. In winter, the bill, legs and feet are black. The juvenile has a black bill and yellow legs, and the feathers of the back have dark margins, giving the bird a distinctly "scaled" appearance. The least tern's small size, white forehead, and yellow bill serve to distinguish it from other terns. Similar Species: The adult sandwich tern (Thalasseus sandvicensis) is the most similar species to the adult least tern, but is much larger at about 38 cm (15 in) in length and has a black bill with a pale (usually yellow) tip and black legs. Juvenile least terns and sandwich terns look very similar in appearance. -

Successful Conservation Measures and New Breeding Records for Damara Terns Sterna Balaenarum in Namibia

Braby et al.: Breeding of Damara Terns Sterna balaenarum in Namibia 81 SUCCESSFUL CONSERVATION MEASURES AND NEW BREEDING RECORDS FOR DAMARA TERNS STERNA BALAENARUM IN NAMIBIA R.J. BRABY1, ANAT SHAPIRA2 & R.E. SIMMONS3 1Resource Management, Ministry of Environment & Tourism, P/Bag 5018, Swakopmund, Namibia 2Ben Gurion University, Beer-Sheva, Israel 3National Biodiversity Programme, Directorate of Environmental Affairs, Ministry of Environment & Tourism, P/Bag 13306, Windhoek, Namibia ([email protected]) Received 19 February 2001, accepted 23 July 2001 SUMMARY BRABY, R.J., SHAPIRA, A. & SIMMONS, R.E. 2001. Successful conservation measures and new breeding records for Damara Terns Sterna balaenarum in Namibia. Marine Ornithology 28: 81–84. Damara Terns Sterna balaenarum nest at high densities on the central Namibian coast and overlap in both space and time with vacationing fishermen and quad bikers. This results in high non-hatching rates of up to 50% and reduced breeding success for the densest known colony of terns. In November 2000, information boards and a barrier preventing off-road vehicles from entering a Damara Tern breeding site near Swakopmund were erected. Comparisons between nesting density, hatching success and vehicles passes before and after these measures showed that nesting density increased slightly (12 to 15 nests/km2/month), hatching success increased from 56% to 80% and vehicle passes dropped from 870 per month to zero. The overall result was a doubling of the number of chicks hatched in the study area. The success of this approach augurs well for similar approaches to other conflicts between semi-colonial coastal-breeding birds and visitors. New breeding records from southern Namibia and a nesting record from 11.5 km inland are also detailed in our attempt to elucidate the ecology and conser- vation of this rare seabird. -

Programs and Field Trips

CONTENTS Welcome from Kathy Martin, NAOC-V Conference Chair ………………………….………………..…...…..………………..….…… 2 Conference Organizers & Committees …………………………………………………………………..…...…………..……………….. 3 - 6 NAOC-V General Information ……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..………….. 6 - 11 Registration & Information .. Council & Business Meetings ……………………………………….……………………..……….………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………………………..…..……...….. 11 6 Workshops ……………………….………….……...………………………………………………………………………………..………..………... 12 Symposia ………………………………….……...……………………………………………………………………………………………………..... 13 Abstracts – Online login information …………………………..……...………….………………………………………….……..……... 13 Presentation Guidelines for Oral and Poster Presentations …...………...………………………………………...……….…... 14 Instructions for Session Chairs .. 15 Additional Social & Special Events…………… ……………………………..………………….………...………………………...…………………………………………………..…………………………………………………….……….……... 15 Student Travel Awards …………………………………………..………...……………….………………………………..…...………... 18 - 20 Postdoctoral Travel Awardees …………………………………..………...………………………………..……………………….………... 20 Student Presentation Award Information ……………………...………...……………………………………..……………………..... 20 Function Schedule …………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………..…………. 22 – 26 Sunday, 12 August Tuesday, 14 August .. .. .. 22 Wednesday, 15 August– ………………………………...…… ………………………………………… ……………..... Thursday, 16 August ……………………………………….…………..………………………………………………………………… …... 23 Friday, 17 August ………………………………………….…………...………………………………………………………………………..... 24 Saturday, -

Sternula Antillarum

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Sternula antillarum (Least Tern) Priority 1 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Aves (Birds) Order: Charadriiformes (Plovers, Sandpipers, And Allies) Family: Laridae (Gulls, Jaegers, Kittiwakes, Skimmers, Skuas, And Terns) General comments: Average 182 pairs in the most recent 10 years, 90% at fewer than 5 discrete nesting areas, need intensive management for reproductive success. The first recorded nesting colony in Maine was at Pine Point, Scarborough in 1961 (Hunter 1975 Auk 92:143-145). Species Conservation Range Maps for Least Tern: Town Map: Sternula antillarum_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Sternula antillarum_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: Maine Status: Endangered State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: NA Regional Endemic: NA High Regional Conservation Priority: Northeast Endangered Species and Wildlife Diversity Technical Committee: Risk: Yes, Data: Yes, Area: No, Spec: No, Warrant Listing: No, Total Categories with "Yes": 2 North American Waterbird Conservation Plan: High Concern United States Birds of Conservation Concern: Bird of Conservation Concern in Bird Conservation Regions 14 and/or 30: Yes High Climate Change Vulnerability: NA Understudied rare taxa: NA Historical: NA Culturally Significant: NA Habitats Assigned to Least Tern: Formation Name Intertidal Macrogroup Name Intertidal Sandy Shore Habitat System Name: Sand Beach **Primary Habitat** Notes: -

California Least Tern (Sternula Antillarum Browni)

California least tern (Sternula antillarum browni) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation u.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office Carlsbad, California September 2006 5-YEARREVIEW California least tern (Sternula antillarum browni) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 1 1.1. REVIEWERS 1 1.2. METHODOLOGY USED TO COMPLETE THE REVIEW: 1 1.3. BACKGROUND: 1 2. REVIEW ANALYSIS 2 2.1. ApPLICATION OF THE 1996 DISTINCT POPULATION SEGMENT (DPS) POLICY 2 2.2. RECOVERY CRITERIA 2 2.3. UPDATED INFORMATION AND CURRENT SPECIES STATUS 5 2.4. SyNTHESIS 22 3. RESULTS 22 3.1. RECOMMENDED CLASSIFICATION 22 3.2. NEW RECOVERY PRIORITY NUMBER 22 3.3. LISTING AND RECLASSIFICATION PRIORITY NUMBER, IF RECLASSIFICATION IS RECOMMENDED 23 4.0 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE ACTIONS 23 5.0 REFERENCES •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 24 11 5-YEAR REVIEW California least tern (Sternula antillarum browni) 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1. Reviewers Lead Region: Diane Elam and Mary Grim, California-Nevada Operations Office, 916- 414-6464 Lead Field Office: Jim A. Bartel, Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Service, 760-431-9440 1.2. Metnodoiogy used to complete the review: This review was compiled by staffofthe Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office (CFWO). The review was completed using documents from office files as well as available literature on the California least tern. 1.3. Background: 1.3.1. FR Notice citation announcing initiation of this review: The notice announcing the initiation ofthis 5-year review and opening ofthe first comment period for 60 days was published on July 7, 2005 (70 FR 39327). A notice reopening the comment period for 60 days was published on November 3, 2005 (70 FR 66842). -

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula Nereis Nereis

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula nereis nereis The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl Image credit: Adult Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) over Rottnest Island, Western Australia © Georgina Steytler © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2019. The National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis), Commonwealth of Australia 2019’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the -

Annual Survival and Breeding Dispersal of a Seabird Adapted to a Stable Environment: Implications for Conservation

J Ornithol DOI 10.1007/s10336-011-0798-7 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Annual survival and breeding dispersal of a seabird adapted to a stable environment: implications for conservation Justine Braby • Sigrid J. Braby • Rodney J. Braby • Res Altwegg Received: 9 December 2010 / Revised: 6 December 2011 / Accepted: 9 December 2011 Ó Dt. Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V. 2012 Abstract Understanding the spatial dynamics of popu- based on AICc favoured a model that suggests local annual lations is essential for conservation of species at the survival of Damara Terns for the dataset was 0.88 (95% CI, landscape level. Species that have adapted to stable 0.73–0.96) and the annual dispersal probability was 0.06 environments may not move from their breeding areas even (0.03–0.12). High survival and low dispersal probabilities if these have become sub-optimal due to anthropogenic are consistent with other seabirds adapted to stable envi- disturbances. Instead, they may breed unsuccessfully or ronments. These estimates contribute to the first baseline choose not to breed at all. Damara Terns Sternula balae- demographic information for the Damara Tern. Low dis- narum feed off the highly productive Benguela Upwelling persal probabilities indicate that current protection of System. They breed on the coastal desert mainland of breeding sites is an important management approach for Namibia where development and off-road driving is protecting the species. threatening breeding areas. We report annual survival and breeding dispersal probabilities of 214 breeding adult Keywords Breeding dispersal Á Fidelity Á Survival Á Damara Terns through capture–mark–recapture at two col- Conservation Á Sternula balaenarum Á Damara Tern onies for 9 years (2001–2009) in central Namibia. -

Order CHARADRIIFORMES: Waders, Gulls and Terns Suborder LARI

Text extracted from Gill B.J.; Bell, B.D.; Chambers, G.K.; Medway, D.G.; Palma, R.L.; Scofield, R.P.; Tennyson, A.J.D.; Worthy, T.H. 2010. Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. 4th edition. Wellington, Te Papa Press and Ornithological Society of New Zealand. Pages 191, 223, 230 & 235-236. Order CHARADRIIFORMES: Waders, Gulls and Terns The family sequence of Christidis & Boles (1994), who adopted that of Sibley et al. (1988) and Sibley & Monroe (1990), is followed here. Suborder LARI: Skuas, Gulls, Terns and Skimmers Condon (1975) and Checklist Committee (1990) recognised three subfamilies within the Laridae (Larinae, Sterninae and Megalopterinae) but this division has not been widely adopted. We follow Gochfeld & Burger (1996) in recognising gulls in one family (Laridae) and terns and noddies in another (Sternidae). The sequence of species for Stercorariidae and Laridae follows Peters (1934) and for Sternidae follows Bridge et al. (2005). Family STERNIDAE Bonaparte: Terns and Noddies Sterninae Bonaparte, 1838: Geogr. Comp. List. Birds: 61 – Type genus Sterna Linnaeus, 1758. Most recommendations from a new study of tern and noddy relationships, based on mtDNA (Bridge et al. 2005), have already been adopted by the Taxonomic Subcommittee of the British Ornithologists’ Union Records Committee (Sangster et al. 2005) and the American Ornithologists’ Union Committee on Classification and Nomenclature (Banks, R.C. et al. 2006). This follows many years of disagreement about the generic classification of terns for which 3–12 genera have recently been used (see Bridge et al. 2005). The genera and their sequence recommended by Bridge et al. -

1 Activity of the California Least Tern (Sternula Antillarum Browni)

Activity of the California Least Tern (Sternula antillarum browni) at Huntington State Beach Orange County, California Prepared by the Santa Ana Watershed Association PO Box 5407 Riverside, CA 92517 Prepared for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Nicole Housel, Sue Hoffman, Richard Zembal Authors Allyson Beckman, Cynthia Coria, Jill Coumoutso, Natalia Doshi, Alec Mang, Lana Nguyen, Christin Whitcraft, Field Investigators 2016 1 INTRODUCTION The California Least Tern (Sternula antillarum browni; hereafter Least Tern), a State and Federally listed endangered species, is a migratory, water-associated bird which returns to coastal California from Central America to breed between April and September. Adults are gray with white under-parts, black cap and lore with a white forehead, black-tipped wings, and a yellow beak with dark tip. Young birds are brownish-gray with a scaly appearance, black head lacking the white triangle on the forehead and a dark beak. California Least Terns are approximately 10 inches in length with a 30-inch wingspan. This once abundant, colonial nesting species inhabits seacoasts, beaches, estuaries, lagoons, lakes, and rivers and prefers to nest on bare or sparsely vegetated sand, soil, or pebbles. Least Tern nesting is characterized by two “waves” (Massey and Atwood 1981). The first wave is typically comprised of experienced breeders while the second wave is predominately second-year birds breeding for the first time. This second wave of nest initiations usually occurs in mid-June. Pairs that lose their first clutch and re-nest may also contribute to the group of second wave nesters. -

Abstracts of Those Ar- Dana L Moseley Ticles Using Packages Tm and Topicmodels in R to Ex- Graham E Derryberry Tract Common Words and Trends

ABSTRACT BOOK Listed alphabetically by last name of presenting author Oral Presentations . 2 Lightning Talks . 161 Posters . 166 AOS 2018 Meeting 9-14 April 2018 ORAL PRESENTATIONS Combining citizen science with targeted monitoring we argue how the framework allows for effective large- for Gulf of Mexico tidal marsh birds scale inference and integration of multiple monitoring efforts. Scientists and decision-makers are interested Evan M Adams in a range of outcomes at the regional scale, includ- Mark S Woodrey ing estimates of population size and population trend Scott A Rush to answering questions about how management actions Robert J Cooper or ecological questions influence bird populations. The SDM framework supports these inferences in several In 2010, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill affected many ways by: (1) monitoring projects with synergistic ac- marsh birds in the Gulf of Mexico; yet, a lack of prior tivities ranging from using approved standardized pro- monitoring data made assessing impacts to these the tocols, flexible data sharing policies, and leveraging population impacts difficult. As a result, the Gulf of multiple project partners; (2) rigorous data collection Mexico Avian Monitoring Network (GoMAMN) was that make it possible to integrate multiple monitoring established, with one of its objectives being to max- projects; and (3) monitoring efforts that cover multiple imize the value of avian monitoring projects across priorities such that projects designed for status assess- the region. However, large scale assessments of these ment can also be useful for learning or describing re- species are often limited, tidal marsh habitat in this re- sponses to management activities. -

Thalasseus Acuflavidus) in Brazil

ISSN (impresso) 0103-5657 ISSN (on-line) 2178-7875 Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia Volume 19 Número 3 www.ararajuba.org.br/sbo/ararajuba/revbrasorn Setembro 2011 Publicada pela Sociedade Brasileira de Ornitologia São Paulo - SP Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 19(3), 358-363 ArtIGO Setembro de 2011 Evaluation of the status of conservation of the Cabot’s Tern (Thalasseus acuflavidus) in Brazil Márcio Amorim Efe1,2 and Sandro Luis Bonatto3 1. Setor de Biodiversidade e Ecologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde (ICBS), Universidade Federal de Alagoas. Avenida Lourival Melo Mota, s/n, Tabuleiro do Martins, CEP 57072‑970, Maceió, AL, Brasil. Corresponding author. E‑Mail: [email protected] 2. Seção de Ornitologia, Museu de História Natural, Universidade Federal de Alagoas. Avenida Lourival Melo Mota, s/n, Tabuleiro do Martins, CEP 57072‑970, Maceió, AL, Brasil. 3. Centro de Biologia Genômica e Molecular, Faculdade de Biociências, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul. Avenida Ipiranga, 6.681, Partenon, CEP 90619‑900, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. E‑Mail: [email protected] Recebido em 13/03/2011. Aceito em 29/06/2011. RESUMO: Avaliação do estado de conservação do trinta-réis-de-bando (Thalasseus acuflavidus) no Brasil. O trinta‑réis‑de‑ bando, Thalasseus acuflavidus é considerado uma das mais vulneráveis espécies costeiras do Brasil. Sua distribuição está limitada ao Caribe, costa atlântica da América do Norte e América do Sul. No Brasil, seus ninhos em pequenas ilhas costeiras estão suscetíveis aos distúrbios humanos. Historicamente suas colônias tem sofrido intensiva coleta de ovos por parte de pescadores, o que contribui severamente com o decréscimo de seu sucesso reprodutivo.