1 Activity of the California Least Tern (Sternula Antillarum Browni)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Monitoring Program for Biodiversity and Non-Indigenous Species in Egypt

UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAM MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN REGIONAL ACTIVITY CENTRE FOR SPECIALLY PROTECTED AREAS National monitoring program for biodiversity and non-indigenous species in Egypt PROF. MOUSTAFA M. FOUDA April 2017 1 Study required and financed by: Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas Boulevard du Leader Yasser Arafat BP 337 1080 Tunis Cedex – Tunisie Responsible of the study: Mehdi Aissi, EcApMEDII Programme officer In charge of the study: Prof. Moustafa M. Fouda Mr. Mohamed Said Abdelwarith Mr. Mahmoud Fawzy Kamel Ministry of Environment, Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) With the participation of: Name, qualification and original institution of all the participants in the study (field mission or participation of national institutions) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS page Acknowledgements 4 Preamble 5 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: Institutional and regulatory aspects 40 Chapter 3: Scientific Aspects 49 Chapter 4: Development of monitoring program 59 Chapter 5: Existing Monitoring Program in Egypt 91 1. Monitoring program for habitat mapping 103 2. Marine MAMMALS monitoring program 109 3. Marine Turtles Monitoring Program 115 4. Monitoring Program for Seabirds 118 5. Non-Indigenous Species Monitoring Program 123 Chapter 6: Implementation / Operational Plan 131 Selected References 133 Annexes 143 3 AKNOWLEGEMENTS We would like to thank RAC/ SPA and EU for providing financial and technical assistances to prepare this monitoring programme. The preparation of this programme was the result of several contacts and interviews with many stakeholders from Government, research institutions, NGOs and fishermen. The author would like to express thanks to all for their support. In addition; we would like to acknowledge all participants who attended the workshop and represented the following institutions: 1. -

First Record of a California Gull for North Carolina

General Field Notes LYNN MOSELEY EIS M. OSYE rth Crln Edtr Sth Crln Edtr prtnt f l prtnt f l Glfrd Cll h Ctdl Grnbr, C 240 Chrltn, SC 240 OICE Publication of any unusual sightings of birds in the Field Notes or Briefs for the Files does not imply that these reports have been accepted into the official Checklist of Birds records for either North or South Carolina. Decisions regarding the official Checklists are made by the respective State Records Committees and will be reported upon periodically in THE CHAT. rt rd f Clfrn Gll fr rth Crln Stephen J. Dinsmore John O. Fussell Jeremy Nance 2600 Glen Burnie 1412 Shepard Street 3259 N 1st Avenue Raleigh, NC 27607 Morehead City, NC 28557 Tucson, AZ 85719 At approximately 1400 h on 29 January 1993, we observed an adult California Gull (Larus californicus) at the Carteret County landfill, located southwest of Newport, North Carolina. We were birding the northwest corner of the landfill when Fussell called our attention to a slightly darker-mantled gull resting with hundreds of other gulls, mostly Herring Gulls (L. argentatus). We immediately recognized the bird as an adult California Gull. We were able to observe and photograph the bird for the nest half hour at distances of 75-100 m. At 1430 the bird suddenly flew south over the dump and we were not able to relocated it over the next 2 hours. Sprn 6 The following is a detailed description of the bird, much of it written immediately after the sighting. The bird was slightly smaller and slimmer than the numerous Herring Gulls surrounding it. -

LEAST TERN Scientific Name: Sternula Antillarum Lesson Other

Common Name: LEAST TERN Scientific Name: Sternula antillarum Lesson Other Commonly Used Names: Little tern, silver turnlet, sea swallow, minute tern, little striker, and killing peter Previously Used Names: Sterna antillarum Family: Laridae Rarity Ranks: G4/S3 State Legal Status: Rare Federal Legal Status: Interior population listed as endangered. Other populations are not federally listed. Federal Wetland Status: N/A Description: Georgia's smallest tern at about 23 cm (9 in) in length with a 50 cm (20 in) wingspread, the least tern is white with pale gray feathers on the back and upper surfaces of the wings, except for a narrow black stripe along the leading edge of the upper wing feathers. The least tern has a black cap with a small patch of white on the forehead. In summer, the adult has a yellow bill with a black tip and yellow to orange feet and legs. Its tail is deeply forked. In winter, the bill, legs and feet are black. The juvenile has a black bill and yellow legs, and the feathers of the back have dark margins, giving the bird a distinctly "scaled" appearance. The least tern's small size, white forehead, and yellow bill serve to distinguish it from other terns. Similar Species: The adult sandwich tern (Thalasseus sandvicensis) is the most similar species to the adult least tern, but is much larger at about 38 cm (15 in) in length and has a black bill with a pale (usually yellow) tip and black legs. Juvenile least terns and sandwich terns look very similar in appearance. -

Nesting Populations of California and Ring-Billed Gulls in California

WESTERN BIR Volume 31, Number 3, 2000 NESTING POPULATIONS OF CLwO AND RING-BI--F-r GULLS IN CALIFORNIA: RECENT SURVEYS AND HISTORICAL STATUS W. DAVID SHUFORD, Point Reyes Bird Observatory(PRBO), 4990 Shoreline Highway, StinsonBeach, California94970 THOMAS P. RYAN, San FranciscoBay Bird Observatory(SFBBO), P.O. Box 247, 1290 Hope Street,Alviso, California 95002 ABSTRACT: Statewidesurveys from 1994 to 1997 revealed33,125 to 39,678 breedingpairs of CaliforniaGulls and at least9611 to 12,660 pairsof Ring-billed Gullsin California.Gulls nested at 12 inland sitesand in San FranciscoBay. The Mono Lake colonywas by far the largestof the CaliforniaGull, holding 70% to 80% of the statepopulation, followed by SanFrancisco Bay with 11% to 14%. ButteValley WildlifeArea, Clear Lake NationalWildlife Refuge, and Honey Lake WildlifeArea were the only othersites that heldover 1000 pairsof CaliforniaGulls. In mostyears, Butte Valley, Clear Lake, Big Sage Reservoir,and Honey Lake togetherheld over 98% of the state'sbreeding Ring-billed Gulls; Goose Lake held9% in 1997. Muchof the historicalrecord of gullcolonies consists of estimatestoo roughfor assessmentof populationtrends. Nevertheless, California Gulls, at least,have increased substantially in recentdecades, driven largely by trendsat Mono Lake and San FranciscoBay (first colonizedin 1980). Irregularoccupancy of some locationsreflects the changing suitabilityof nestingsites with fluctuatingwater levels.In 1994, low water at six sites allowedcoyotes access to nestingcolonies, and resultingpredation appeared to reducenesting success greatly at threesites. Nesting islands secure from predators and humandisturbance are nestinggulls' greatest need. Conover(1983) compileddata suggestingthat breedingpopulations of Ring-billed(Larus delawarensis)and California(Larus californicus)gulls haveincreased greafiy in the Westin recentdecades. Detailed assessments of populationstatus and trends of these speciesin individualwestern states, however,have been publishedonly for Washington(Conover et al. -

Magnolia Plantation and Gardens Birdwalk Newsletter 5.7.2017 Walks Conducted by Perry Nugent Articles Written by Jayne J Matney All Owl Photos by Guenter Weber

Magnolia Plantation and Gardens BirdWalk Newsletter 5.7.2017 Walks Conducted by Perry Nugent Articles Written by Jayne J Matney All Owl Photos By Guenter Weber “The owl,” he was saying, “is one of the most curious creatures. A bird that stays awake when the rest of the world sleeps. They can see in the dark. I find that so interesting, to be mired in reality when the rest of the world is dreaming. What does he see and what does he know that the rest of the world is missing?” M.J. Rose Barred Owls: Strix varia Owls capture our curiosity at an early age because of their unique characteristics and the mystery that seems to surround them. Being mostly nocturnal and highly camouflaged, sighting an owl in the day is fairly rare and is very exciting when it happens. Owls in general range in sizes and coloration. Here on our plantation, especially during mating and nesting season, sightings are made and amazing photos have been turned in for our pleasure. The Barred Owl sightings and photos have been the inspiration for the article this week. Barred Owls are large owls (40 to 64 cm long or 16 to 26 inches), native to eastern United States, and named after their distinct bar coloration on their feathers of the chest and belly. The bars on the chest are horizontal, while the bars on the belly are vertical. The rest of the body is mostly a mottled gray-brown. They possess a pale face with dark rings radiating about the eyes, and incredible dark brown eyes unlike other owls that have yellow eyes. -

The Herring Gull Complex (Larus Argentatus - Fuscus - Cachinnans) As a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations

The Herring Gull Complex (Larus argentatus - fuscus - cachinnans) as a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations Dorit Liebers-Helbig, Viviane Sternkopf, Andreas J. Helbig{, and Peter de Knijff Abstract Under what circumstances speciation in sexually reproducing animals can occur without geographical disjunction is still controversial. According to the ring species model, a reproductive barrier may arise through “isolation-by-distance” when peripheral populations of a species meet after expanding around some uninhabitable barrier. The classical example for this kind of speciation is the herring gull (Larus argentatus) complex with a circumpolar distribution in the northern hemisphere. An analysis of mitochondrial DNA variation among 21 gull taxa indicated that members of this complex differentiated largely in allopatry following multiple vicariance and long-distance colonization events, not primarily through “isolation-by-distance”. In a recent approach, we applied nuclear intron sequences and AFLP markers to be compared with the mitochondrial phylogeography. These markers served to reconstruct the overall phylogeny of the genus Larus and to test for the apparent biphyletic origin of two species (argentatus, hyperboreus) as well as the unex- pected position of L. marinus within this complex. All three taxa are members of the herring gull radiation but experienced, to a different degree, extensive mitochon- drial introgression through hybridization. The discrepancies between the mitochon- drial gene tree and the taxon phylogeny based on nuclear markers are illustrated. 1 Introduction Ernst Mayr (1942), based on earlier ideas of Stegmann (1934) and Geyr (1938), proposed that reproductive isolation may evolve in a single species through D. Liebers-Helbig (*) and V. Sternkopf Deutsches Meeresmuseum, Katharinenberg 14-20, 18439 Stralsund, Germany e-mail: [email protected] P. -

Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Appendix J /USFWS Malcolm Grant 2011 Fencing exclosure to protect shorebirds from predators Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Background and Introduction Background and Introduction Throughout North America, the presence of a single mammalian predator (e.g., coyote, skunk, and raccoon) or avian predator (e.g., great horned owl, black-crowned night-heron) at a nesting site can result in adult bird mortality, decrease or prevent reproductive success of nesting birds, or cause birds to abandon a nesting site entirely (Butchko and Small 1992, Kress and Hall 2004, Hall and Kress 2008, Nisbet and Welton 1984, USDA 2011). Depredation events and competition with other species for nesting space in one year can also limit the distribution and abundance of breeding birds in following years (USDA 2011, Nisbet 1975). Predator and competitor management on Monomoy refuge is essential to promoting and protecting rare and endangered beach nesting birds at this site, and has been incorporated into annual management plans for several decades. In 2000, the Service extended the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Nesting Season Operating Procedure, Monitoring Protocols, and Competitor/Predator Management Plan, 1998-2000, which was expiring, with the intent to revise and update the plan as part of the CCP process. This appendix fulfills that intent. As presented in chapter 3, all proposed alternatives include an active and adaptive predator and competitor management program, but our preferred alternative is most inclusive and will provide the greatest level of protection and benefit for all species of conservation concern. The option to discontinue the management program was considered but eliminated due to the affirmative responsibility the Service has to protect federally listed threatened and endangered species and migratory birds. -

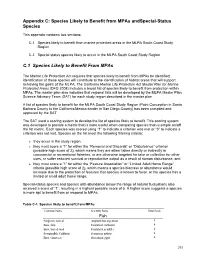

List of Species Likely to Benefit from Marine Protected Areas in The

Appendix C: Species Likely to Benefit from MPAs andSpecial-Status Species This appendix contains two sections: C.1 Species likely to benefit from marine protected areas in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.2 Special status species likely to occur in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.1 Species Likely to Benefit From MPAs The Marine Life Protection Act requires that species likely to benefit from MPAs be identified; identification of these species will contribute to the identification of habitat areas that will support achieving the goals of the MLPA. The California Marine Life Protection Act Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (DFG 2008) includes a broad list of species likely to benefit from protection within MPAs. The master plan also indicates that regional lists will be developed by the MLPA Master Plan Science Advisory Team (SAT) for each study region described in the master plan. A list of species likely to benefit for the MLPA South Coast Study Region (Point Conception in Santa Barbara County to the California/Mexico border in San Diego County) has been compiled and approved by the SAT. The SAT used a scoring system to develop the list of species likely to benefit. This scoring system was developed to provide a metric that is more useful when comparing species than a simple on/off the list metric. Each species was scored using “1” to indicate a criterion was met or “0” to indicate a criterion was not met. Species on the list meet the following filtering criteria: they occur in the study region, they must score a “1” for either -

Programs and Field Trips

CONTENTS Welcome from Kathy Martin, NAOC-V Conference Chair ………………………….………………..…...…..………………..….…… 2 Conference Organizers & Committees …………………………………………………………………..…...…………..……………….. 3 - 6 NAOC-V General Information ……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..………….. 6 - 11 Registration & Information .. Council & Business Meetings ……………………………………….……………………..……….………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………………………..…..……...….. 11 6 Workshops ……………………….………….……...………………………………………………………………………………..………..………... 12 Symposia ………………………………….……...……………………………………………………………………………………………………..... 13 Abstracts – Online login information …………………………..……...………….………………………………………….……..……... 13 Presentation Guidelines for Oral and Poster Presentations …...………...………………………………………...……….…... 14 Instructions for Session Chairs .. 15 Additional Social & Special Events…………… ……………………………..………………….………...………………………...…………………………………………………..…………………………………………………….……….……... 15 Student Travel Awards …………………………………………..………...……………….………………………………..…...………... 18 - 20 Postdoctoral Travel Awardees …………………………………..………...………………………………..……………………….………... 20 Student Presentation Award Information ……………………...………...……………………………………..……………………..... 20 Function Schedule …………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………..…………. 22 – 26 Sunday, 12 August Tuesday, 14 August .. .. .. 22 Wednesday, 15 August– ………………………………...…… ………………………………………… ……………..... Thursday, 16 August ……………………………………….…………..………………………………………………………………… …... 23 Friday, 17 August ………………………………………….…………...………………………………………………………………………..... 24 Saturday, -

22 First Certain Record of California Gull (Larus

22 NOTES Florida Field Naturalist 28(1):22-24, 2000. FIRST CERTAIN RECORD OF CALIFORNIA GULL (LARUS CALIFORNICUS) IN FLORIDA DOUGLAS B. MCNAIR Tall Timbers Research Station, 13093 Henry Beadel Drive, Tallahassee, Florida 32312-0918 The status of California Gull (Larus californicus) in Florida, prior to this record, is unresolved. Robertson and Woolfenden (1992) placed California Gull on their unverified list, while Stevenson and Anderson (1994) placed it on their accredited list (see Wool- fenden et al. 1996). I follow the criteria of Robertson and Woolfenden (1992). Gulls in their third winter were photographed in Pinellas County in 1978 and 1979; species identification was not considered certain although the birds probably were California Gulls (Robertson and Woolfenden 1992, Stevenson and Anderson 1994). Following the ambiguous photographs, six sight observations of California Gulls have been reported. The Florida Ornithological Society Records Committee (FOSRC) rejected two reports; two undetailed reports never reviewed by the FOSRC lack documentation (Baker 1991a, b; Stevenson and Anderson 1994); and two detailed reports (a bird seen in late October 1982 [Stevenson and Anderson 1994] and an adult in February 1983 [Powell 1986, FOSRC]) are valid, although formal documentation is lacking for each. Both valid reports occurred on the peninsula, one on Gulf coast (Pinellas County), the other on the Atlantic coast (Brevard County). I discovered a first-winter California Gull at Apalachicola, Franklin County, on 26 Sep- tember 1998, when Hurricane Georges was more than 300 km offshore. Sustained winds at Apalachicola were about 50 km. The bird was associated with a mixed flock of gulls, terns, and skimmers resting on a partially flooded vacant lot at the tip of a small penin- sula at the mouth of the Apalachicola River. -

Inventory of Terns, Laughing Gulls, and Black Skimmers Nesting in Massachusetts in 2010

INVENTORY OF TERNS, LAUGHING GULLS, AND BLACK SKIMMERS NESTING IN MASSACHUSETTS IN 2010 Juvenile Roseate Tern, Massachusetts. Prepared by: Carolyn S. Mostello Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program Rte. 135, Westborough, MA 01581 August 2011 Abstract Cooperators in Massachusetts surveyed more than 141 coastal sites in 2010 for the presence of breeding Roseate Terns (Sterna dougallii), Common Terns (Sterna hirundo), Arctic Terns (Sterna paradisaea), Least Terns (Sternula antillarum), Laughing Gulls (Larus atricilla), and Black Skimmers (Rhynchops niger). Eighty sites were occupied by nesting birds of one or more of these species. Roseate Terns increased 4.0% to 1,393 pairs. Common Terns and Least Terns were stable at 16,224 and 3,484 pairs, respectively. Laughing Gulls decreased 23.3% to 1,249 pairs. Five pairs of Black Skimmers nested during the peak of the season and three pairs nested late. Two-and-a-half pairs of Arctic Terns nested during the peak. Introduction Coastal waterbirds are a vulnerable group of species. Of Massachusetts’ four nesting tern species, the Common Tern, the Least Tern and the Arctic Tern are listed as “Special Concern” pursuant to the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act. The Roseate Tern is listed as “Endangered” pursuant to both the Massachusetts and U.S. Endangered Species Acts. Terns, Laughing Gulls, and Black Skimmers in Massachusetts are protected and monitored by an extensive network of cooperators throughout the state. These cooperators provide census data and other reproductive information to the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife (MDFW). This allows wildlife managers to determine abundance and status of, and threats to, these species. -

Sternula Antillarum

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Sternula antillarum (Least Tern) Priority 1 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Aves (Birds) Order: Charadriiformes (Plovers, Sandpipers, And Allies) Family: Laridae (Gulls, Jaegers, Kittiwakes, Skimmers, Skuas, And Terns) General comments: Average 182 pairs in the most recent 10 years, 90% at fewer than 5 discrete nesting areas, need intensive management for reproductive success. The first recorded nesting colony in Maine was at Pine Point, Scarborough in 1961 (Hunter 1975 Auk 92:143-145). Species Conservation Range Maps for Least Tern: Town Map: Sternula antillarum_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Sternula antillarum_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: Maine Status: Endangered State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: NA Regional Endemic: NA High Regional Conservation Priority: Northeast Endangered Species and Wildlife Diversity Technical Committee: Risk: Yes, Data: Yes, Area: No, Spec: No, Warrant Listing: No, Total Categories with "Yes": 2 North American Waterbird Conservation Plan: High Concern United States Birds of Conservation Concern: Bird of Conservation Concern in Bird Conservation Regions 14 and/or 30: Yes High Climate Change Vulnerability: NA Understudied rare taxa: NA Historical: NA Culturally Significant: NA Habitats Assigned to Least Tern: Formation Name Intertidal Macrogroup Name Intertidal Sandy Shore Habitat System Name: Sand Beach **Primary Habitat** Notes: