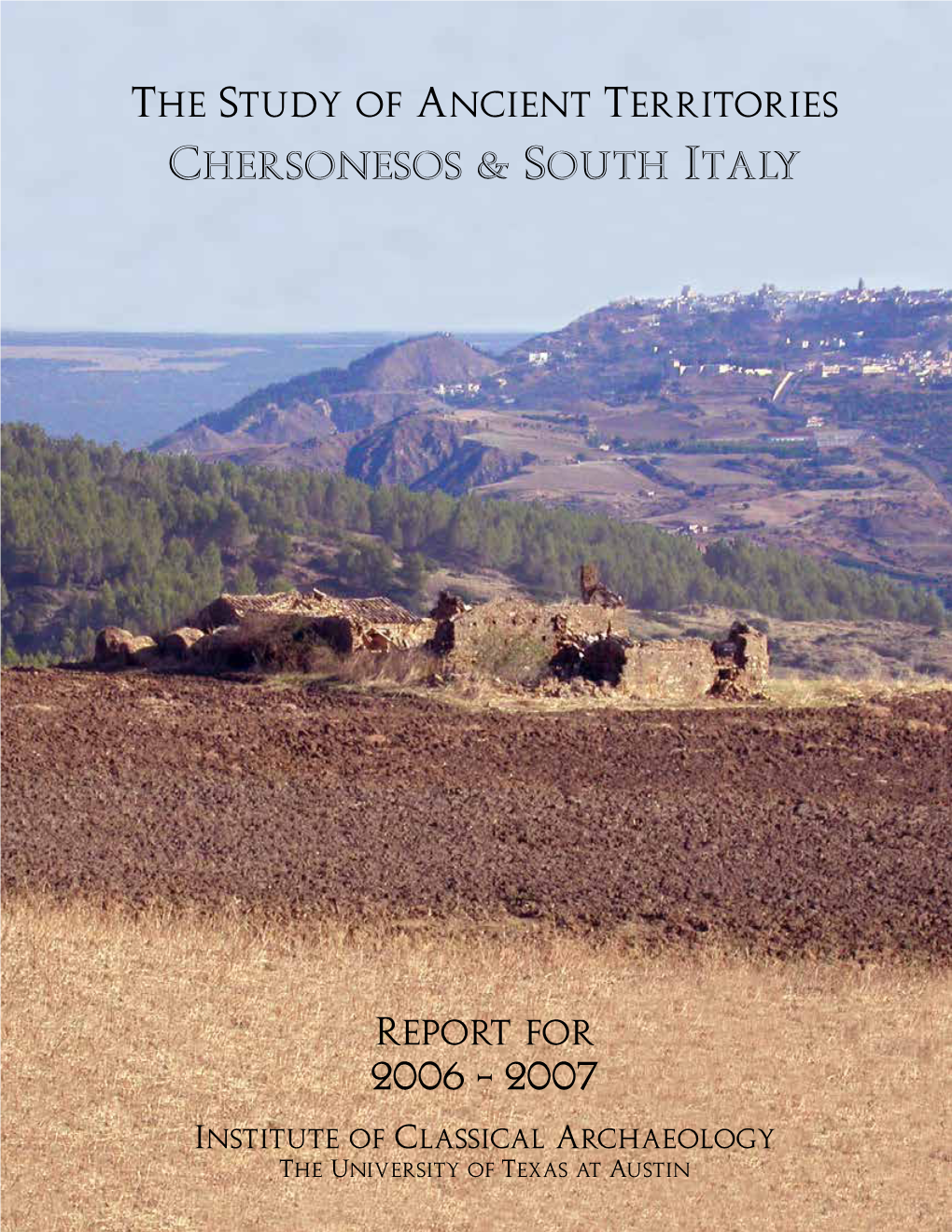

Chersonesos, 2006-2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Planning in the Greek Colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia

Urban Planning in the Greek Colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia (8th – 6th centuries BCE) An honors thesis for the Department of Classics Olivia E. Hayden Tufts University, 2013 Abstract: Although ancient Greeks were traversing the western Mediterranean as early as the Mycenaean Period, the end of the “Dark Age” saw a surge of Greek colonial activity throughout the Mediterranean. Contemporary cities of the Greek homeland were in the process of growing from small, irregularly planned settlements into organized urban spaces. By contrast, the colonies founded overseas in the 8th and 6th centuries BCE lacked any pre-existing structures or spatial organization, allowing the inhabitants to closely approximate their conceptual ideals. For this reason the Greek colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia, known for their extensive use of gridded urban planning, exemplified the overarching trajectory of urban planning in this period. Over the course of the 8th to 6th centuries BCE the Greek cities in Sicily and Magna Graecia developed many common features, including the zoning of domestic, religious, and political space and the implementation of a gridded street plan in the domestic sector. Each city, however, had its own peculiarities and experimental design elements. I will argue that the interplay between standardization and idiosyncrasy in each city developed as a result of vying for recognition within this tight-knit network of affluent Sicilian and South Italian cities. This competition both stimulated the widespread adoption of popular ideas and encouraged the continuous initiation of new trends. ii Table of Contents: Abstract. …………………….………………………………………………………………….... ii Table of Contents …………………………………….………………………………….…….... iii 1. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………..……….. 1 2. -

Herakles Iconography on Tyrrhenian Amphorae

HERAKLES ICONOGRAPHY ON TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE _____________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia _____________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ______________________________________________ by MEGAN LYNNE THOMSEN Dr. Susan Langdon, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Susan Langdon, and the other members of my committee, Dr. Marcus Rautman and Dr. David Schenker, for their help during this process. Also, thanks must be given to my family and friends who were a constant support and listening ear this past year. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS……………………………………………………………..v Chapter 1. TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE—A BRIEF STUDY…..……………………....1 Early Studies Characteristics of Decoration on Tyrrhenian Amphorae Attribution Studies: Identifying Painters and Workshops Market Considerations Recent Scholarship The Present Study 2. HERAKLES ON TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE………………………….…30 Herakles in Vase-Painting Herakles and the Amazons Herakles, Nessos and Deianeira Other Myths of Herakles Etruscan Imitators and Contemporary Vase-Painting 3. HERAKLES AND THE FUNERARY CONTEXT………………………..…48 Herakles in Etruria Etruscan Concepts of Death and the Underworld Etruscan Funerary Banquets and Games 4. CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………..67 iii APPENDIX: Herakles Myths on Tyrrhenian Amphorae……………………………...…72 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………..77 ILLUSTRATIONS………………………………………………………………………82 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Tyrrhenian Amphora by Guglielmi Painter. Bloomington, IUAM 73.6. Herakles fights Nessos (Side A), Four youths on horseback (Side B). Photos taken by Megan Thomsen 82 2. Tyrrhenian Amphora (Beazley #310039) by Fallow Deer Painter. Munich, Antikensammlungen 1428. Photo CVA, MUNICH, MUSEUM ANTIKER KLEINKUNST 7, PL. 322.3 83 3. Tyrrhenian Amphora (Beazley #310045) by Timiades Painter (name vase). -

Bernalda - Metaponto Scalo Quadro Delle Corse: ANDATA

Linea: 344 - Matera - Bernalda - Metaponto Scalo Quadro delle Corse: ANDATA ORARIO VALIDO DAL 01/10/2019 ATTUALMENTE IN VIGORE Frequenza Scolastica Scolastica Scolastica Non Scol Scol Feriale Note - 1 2 - 3 - Matera - Piazzale Matteotti 06:45 13:30 13:30 14:10 14:30 18:10 Matera- Ospedale Maria SS delle Grazie 06:48 13:33 13:33 14:13 14:33 18:13 Matera - Via Levi - 13:35 13:35 - 14:35 - Innesto SP 10/SS 7 07:00 13:45 13:45 14:25 14:45 18:25 Innesto SS. 7/SS 380 07:15 14:00 14:00 14:40 15:00 18:40 Bernalda Bivio 07:25 14:10 14:10 14:50 15:10 18:50 Bernalda C.so Umberto 07:35 - - - - - Bernalda P.zza Plebiscito - 14:20 14:20 15:00 15:20 19:00 Metaponto Borgo / SC 07:50 - - - - - Note: 1) Partenza ore 13:15 da Istituti scolastici C.da Rondinelle per Piazzale Matteotti 2) Partenza Via Mattei Istituti scolastici ore 13:20 - Piazzale Matteotti - Uscita Matera Sud 3) Partenza Via Mattei Istituti scolastici ore 14:20 - Piazzale Matteotti - Uscita Matera Sud N.B. Da Matera per Bernalda, nel periodo non scolastico, c'è la possibilità di prendere il bus delle 6:20 da Piazzale Matteotti per Policoro (Linea 354) ed effettuare cambio autobus sulla SS 175 con Bus in coincidenza proveniente da Montescaglio (Linea 337) e diretto a Bernalda - Policoro, con arrivo a Bernalda in P.zza Plebiscito alle ore 6:55 N.B. Prestare attenzione alle partenze in quanto le suddette corse possono essere espletate oltre che dalla Sita Sud, anche da consorziati Cotrab (Società Chiruzzi) Andata pagina 1 di 3 Linea: 344 - Matera - Bernalda - Metaponto Scalo Quadro delle Corse: RITORNO ORARIO VALIDO DAL 01/10/2019 ATTUALMENTE IN VIGORE Frequenza Feriale Scolastica Scolastica Scolastica Feriale Note 1 2 3 - 4 Metaponto Borgo / SC - - - 14:00 - Bernalda P.zza Plebiscito 07:00 07:00 07:00 - 17:00 Bernalda C.so Umberto - - - 14:15 - Bernalda Bivio 07:10 07:10 07:10 14:25 17:10 Innesto SS. -

Medici Convenzionati Con La ASM Elencati Per Ambiti Di Scelta

DIPARTIMENTO CURE PRIMARIE S.S. Organizzazione Assistenza Primaria MMG, PLS, CA Medici Convenzionati con la ASM Elencati per Ambiti di Scelta Ambito : Accettura - Aliano - Cirigliano - Gorgoglione - San Mauro Forte - Stigliano 80 DEFINA/DOMENICA Accettura VIA IV NOVEMBRE 63 bis 63 bis 9930 SARUBBI/ANTONELLA STIGLIANO Corso Vittorio Emanuele II 45 308 SANTOMASSIMO/LUIGINA MIRIAM Aliano VIA DELLA VITTORIA 4 8794 MORMANDO/ANTONIO Cirigliano VIA FONTANA 8 8794 MORMANDO/ANTONIO Gorgoglione via DE Gasperi 30 3 BELMONTE/ROCCO San Mauro Forte VIA FRATELLI CATALANO 5 4374 MANDILE/FRANCESCO San Mauro Forte CORSO UMBERTO I 14 4242 CASTRONUOVO/ANTONIO Stigliano CORSO UMBERTO 57 8474 DIGILIO/MARGHERITA CARMELA Stigliano Corso Umberto I° 29 9382 DIRUGGIERO/MARGHERITA Stigliano Via Zanardelli 58 Ambito : Bernalda 9292 CALBI/MARISA Bernalda VIALE EUROPA - METAPONTO 10 9114 CARELLA/GIOVANNA Bernalda VIA DEL CONCILIO VATICANO II 35 8523 CLEMENTELLI/GREGORIO Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 7468 GRIECO/ANGELA MARIA Bernalda VIALE BERLINGUER 15 7708 MATERI/ANNA MARIA Bernalda PIAZZA PLEBISCITO 4 9283 PADULA/PIETRO SALVATORE Bernalda VIA MONTESCAGLIOSO 28 9698 QUINTO/FRANCESCA IMMACOLATA Bernalda Via Nuova Camarda 24 4366 TATARANNO/RAFFAELE Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 327 TOMASELLI/ISABELLA Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 9918 VACCARO/ALMERINDO Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 8659 VITTI/MARIA ANTONIETTA Bernalda VIA TRIESTE 14 Ambito : Calciano - Garaguso - Oliveto Lucano - Tricarico MEDICO INCARICATO Calciano DISTRETTO DI CALCIANO S.N.C. MEDICO INCARICATO Oliveto Lucano -

Rivendite Biglietti

Agenzie associate a Seat s.r.l. Ragione Sociale Indirizzo Provincia Comune Telefono ACQUARICA DEL CAPO - EMPORIO DEL TABACCO DI SALVATORE CASSIANO CORSO DANTE, 99/B Lecce Acquarica del Capo 0833 721262 ALESSANO - CIARDO GIANLUIGI - RIV. TAB PIAZZA DON TONINO BELLO, 34 - ALESSANO Lecce Alessano 0833 524274 ALEZIO - AMICO MARIA GRAZIA - EDICOLA & LIBRERIA VIA MARIANA ALBINA, 27 - ALEZIO Lecce Alezio 0833 281125 ALEZIO - TABACCHERIA N. 2 BRAY ROSA VIA ROMA, 232 - ALEZIO Lecce Alezio 0833 283031 ANDRANO - RIZZO "EDICOLA & CARTOLERIA" VIA XXV LUGLIO - ANDRANO Lecce Andrano 0836 926017 ANDRANO - TABACCHI ACCOGLI LUIGI VIA NAPOLI 48 Lecce Andrano 0836 926096 BARBARANO - TABACCHI RIZZELLO DI RIZZELLO MICHELE VIA DI MEZZO, 1/3 Lecce Morciano di Leuca BRINDISI - COSACCO ANTONELLO TABACCHI VIA APPIA - BRINDISI Brindisi Brindisi 0831 513972 CASARANO - LEOPIZZI PAOLO - RIV. TAB. CORSO XX SETTEMBRE, 129 - CASARANO Lecce Casarano 0833 513569 CASTIGLIONE - COLLUTO ANNAMARIA - RIV. TAB. 2 VIA TRENTO, 3 Lecce Andrano 0836 929226 CASTRIGNANO DEL CAPO - CHETTA PATRIZIA PIAZZA SAN MICHELE Lecce Castrignano del Capo 0833 530864 CASTRO - CIULLO ANTONIO - ST. SERV. API S. P. CASTRO-VIGNACASTRISI - CASTRO Lecce Castro 0836 943034 CASTRO - VALGUARNERA EMILIO - RIV. TAB. PIAZZA DANTE ALIGHIERI, 12 - CASTRO Lecce Castro 0836 947429 COLLEPASSO - ORLANDO ANNA LUCIA - NON SOLO EDICOLA VIA C. ROLLO, 22 Lecce Collepasso 0833 345388 CORSANO - LA COCCINELLA DI RISO ANTONIO VIA TEVERE, 30 Lecce Corsano 0833533304 DEPRESSA - CRISOSTOMO COSIMA RIV. TAB. N° 5 VIA BRENTA, 5 Lecce Tricase 0833 771271 DISO - EURO BAR SAS Di ALEMANNO ANDREA & CO PIAZZA CARLO ALBERTO 17 Lecce Diso 320 3507585 GAGLIANO DEL CAPO - TIERRAMAR SAS VIA UNITA' D'ITALIA Lecce Gagliano del Capo 0833 548728 GALATONE - VAINIGLIA SEBASTIANO - RIV. -

Crossroads 360 Virtual Tour Script Edited

Crossroads of Civilization Virtual Tour Script Note: Highlighted text signifies content that is only accessible on the 360 Tour. Welcome to Crossroads of Civilization. We divided this exhibit not by time or culture, but rather by traits that are shared by all civilizations. Watch this video to learn more about the making of Crossroads and its themes. Entrance Crossroads of Civilization: Ancient Worlds of the Near East and Mediterranean Crossroads of Civilization looks at the world's earliest major societies. Beginning more than 5,000 years ago in Egypt and the Near East, the exhibit traces their developments, offshoots, and spread over nearly four millennia. Interactive timelines and a large-scale digital map highlight the ebb and flow of ancient cultures, from Egypt and the earliest Mesopotamian kingdoms of the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, to the vast Persian, Hellenistic, and finally Roman empires, the latter eventually encompassing the entire Mediterranean region. Against this backdrop of momentous historical change, items from the Museum's collections are showcased within broad themes. Popular elements from classic exhibits of former years, such as our Greek hoplite warrior and Egyptian temple model, stand alongside newly created life-size figures, including a recreation of King Tut in his chariot. The latest research on our two Egyptian mummies features forensic reconstructions of the individuals in life. This truly was a "crossroads" of cultural interaction, where Asian, African, and European peoples came together in a massive blending of ideas and technologies. Special thanks to the following for their expertise: ● Dr. Jonathan Elias - Historical and maps research, CT interpretation ● Dr. -

Classical Images – Greek Pegasus

Classical images – Greek Pegasus Red-figure kylix crater Attic Red-figure kylix Triptolemus Painter, c. 460 BC attr Skythes, c. 510 BC Edinburgh, National Museums of Scotland Boston, MFA (source: theoi.com) Faliscan black pottery kylix Athena with Pegasus on shield Black-figure water jar (Perseus on neck, Pegasus with Etrurian, attr. the Sokran Group, c. 350 BC Athenian black-figure amphora necklace of bullae (studs) and wings on feet, Centaur) London, The British Museum (1842.0407) attr. Kleophrades pntr., 5th C BC From Vulci, attr. Micali painter, c. 510-500 BC 1 New York, Metropolitan Museum of ART (07.286.79) London, The British Museum (1836.0224.159) Classical images – Greek Pegasus Pegasus Pegasus Attic, red-figure plate, c. 420 BC Source: Wikimedia (Rome, Palazzo Massimo exh) 2 Classical images – Greek Pegasus Pegasus London, The British Museum Virginia, Museum of Fine Arts exh (The Horse in Art) Pegasus Red-figure oinochoe Apulian, c. 320-10 BC 3 Boston, MFA Classical images – Greek Pegasus Silver coin (Pegasus and Athena) Silver coin (Pegasus and Lion/Bull combat) Corinth, c. 415-387 BC Lycia, c. 500-460 BC London, The British Museum (Ac RPK.p6B.30 Cor) London, The British Museum (Ac 1979.0101.697) Silver coin (Pegasus protome and Warrior (Nergal?)) Silver coin (Arethusa and Pegasus Levantine, 5th-4th C BC Graeco-Iberian, after 241 BC London, The British Museum (Ac 1983, 0533.1) London, The British Museum (Ac. 1987.0649.434) 4 Classical images – Greek (winged horses) Pegasus Helios (Sol-Apollo) in his chariot Eos in her chariot Attic kalyx-krater, c. -

9. Mobility and Transitions: the South-Central Mediterranean on the Eve of History

Davide Tanasi and Nicholas C. Vella (eds), Site, artefacts and landscape - Prehistoric Borġ in-Nadur, Malta, 251-282 ©2011 Polimetrica International Scientific Publisher Monza/Italy 9. Mobility and transitions: the south-central Mediterranean on the eve of history Nicholas C. Vella – Department of Classics and Archaeology, University of Malta, Malta [email protected] Davide Tanasi – Arcadia University, The College of Global Studies, MCAS, Italy [email protected] Maxine Anastasi – Department of Classics and Archaeology, University of Malta, Malta [email protected] Abstract. This paper reviews the evidence for maritime connections between Malta and Sicily in the second millennium BC and considers their social implications. Since much of what has been written by antiquarians and archaeologists about the islands was often the result of more modern maritime connections and knowledge transfer between local and foreign scholars, we begin by arguing for the relevance of a spatially oriented history of archaeological thought and practice. 9.1. Introduction Mobility is the hallmark of the Bronze and early Iron ages, not only movement of humans across the Mediterranan but with them ideas, beliefs, and ways of doing. The invention of the sail somewhere along the eastern shores of the Middle Sea resulted in what Broodbank has called ‘the shrinkage of the Mediterranean’, a process which brought easterners ever closer to the islands and coastal regions of the centre of that sea from about the mid-second 252 Nicholas C. Vella, Davide Tanasi, Maxine Anastasi millennium BC1. This is not to say that mobility did not occur in earlier periods in prehistory: the obsidian exchange system tells us much about movement in the Neolithic2 whereas the phenomenon related to the distribution of Beaker pottery during the Chalcolithic/Early Bronze Age is now being explained in part by reference to a structured interaction involving small-scale population movements between regions3. -

Red-Figured Pottery from Corinth Plate 64

RED-FIGUREDPOTTERY FROM CORINTH SACRED SPRING AND ELSEWHERE (PLATES 63-74) THE PRESENT ARTICLE publishes the inventoried pieces of Attic red-figured pottery discovered during the excavations of the Sacred Spring. Four fragments, 49-52, belong to an unidentified fabric which does not appear to be Attic. The article also includes fragments from the Peribolos of Apollo and the Lechaion Road East, and ends with two miscellaneous sherds and an importantstemless cup. This is, in fact, the first of two articles which will cover most of the Attic red figure that has been found at Corinth since 1957.1The second article will deal with the pottery from the recent exca- vations in the central and southwesternarea of the Forum. Some 71 pieces, mainly fragments, are presented here: 52 (1-52) come from the Sacred Spring, 6 (53-58) from the Peribolos of Apollo, 10 (59-68) from excavations below Roman Shop V, east of the Lechaion Road, 3 (69-71) from various findspots. The catalogue is arrangedby shape and, within each shape, by date so far as possible. A. SACRED SPRING (Pls. 63-69) The early excavations in the Sacred Spring were published by B. H. Hill. The area was re-examined from 1968 to 1970 and again in 1972, during which eight architectural phases were distinguished, the earliest beginning in the later 8th century, the latest ending with the destruction of Corinth in 146 B.C.2 All the inventoried Attic red figure from the new excavations is listed in the following catalogue, but other fragments, of less significance, are kept in the relevant Corinth pottery lots. -

The Art and Archaeology of Ancient Greece Judith M

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00123-7 - The Art and Archaeology of Ancient Greece Judith M. Barringer Frontmatter More information The Art and This richly illustrated, color textbook introduces the art and Archaeology of archaeology of ancient Greece, from the Bronze Age through the Roman conquest. Suitable for students with no prior knowledge of Ancient Greece ancient art, this book reviews the main objects and monuments of the ancient Greek world, emphasizing the context and function of these artefacts in their particular place and time. Students are led to a rich understanding of how objects were meant to be perceived, what “messages” they transmitted, and how the surrounding environment shaped their meaning. The book includes more than 500 illustrations (with over 400 in color), including specially commissioned photographs, maps, fl oorplans, and reconstructions. Judith Barringer examines a variety of media, including marble and bronze sculpture, public and domestic architecture, painted vases, coins, mosaics, terracotta fi gurines, reliefs, jewelry, armor, and wall paintings. Numerous text boxes, chapter summaries, and timelines, complemented by a detailed glossary, support student learning. • More than 500 illustrations, with over 400 in color, including specially commissioned photographs, maps, plans, and reconstructions • Includes text boxes, chapter summaries and timelines, and detailed glossary • Looks at Greek art from the perspectives of both art history and archaeology, giving students an understanding of the historical and everyday context of art objects Judith M. Barringer is Professor of Greek Art and Archaeology in Classics at the University of Edinburgh. Her areas of specialization are Greek art and archaeology and Greek history, myth, and religion. -

Catalogue 8 Autumn 2020

catalogue 8 14-16 Davies Street london W1K 3DR telephone +44 (0)20 7493 0806 e-mail [email protected] WWW.KalloSgalleRy.com 1 | A EUROPEAN BRONZE DIRK BLADE miDDle BRonze age, ciRca 1500–1100 Bc length: 13.9 cm e short sword is thought to be of english origin. e still sharp blade is ogival in form and of rib and groove section. in its complete state the blade would have been completed by a grip, and secured to it by bronze rivets. is example still preserves one of the original rivets at the butt. is is a rare form, with wide channels and the midrib extending virtually to the tip. PRoVenance Reputedly english With H.a. cahn (1915–2002) Basel, 1970s–90s With gallery cahn, prior to 2010 Private collection, Switzerland liteRatuRe Dirks are short swords, designed to be wielded easily with one hand as a stabbing weapon. For a related but slightly earlier in date dagger or dirk with the hilt still preserved, see British museum: acc. no. 1882,0518.6, which was found in the River ames. For further discussion of the type, cf. J. evans, e Ancient Bronze Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain and Ireland, london, 1881; S. gerloff and c.B. Burgess, e Dirks and Rapiers of Great Britain and Ireland, abteilung iV: Band 7, munich, Beck, 1981. 4 5 2 | TWO GREEK BRONZE PENDANT BIRD)HEAD PYXIDES PRoVenance christie’s, london, 14 may 2002, lot 153 american private collection geometRic PeRioD, ciRca 10tH–8tH centuRy Bc Heights: 9.5 cm; 8 cm liteRatuRe From northern greece, these geometric lidded pendant pyxides are called a ‘sickle’ type, one with a broad tapering globular body set on a narrow foot that flares at the base; the other and were most likely used to hold perfumed oils or precious objects. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00962-2 - Land and Privilege in Byzantium: The Institution of Pronoia Mark C. Bartusis Index More information Index Aaron on Zavorda Treatise, 35 archontopoulos, grant recipient, 348 Aitolia, 231 Theodore, apographeus, 627 Akapniou, monastery in Thessaloniki, 307, Achaia, 234, 241 556, 592–94, 618 Acheloos, theme of, 233 Akarnania, 333, 510 Achinos, village, 556, 592–94 akatadoulotos, akatadouloton, 308, 423–24, 425 Achladochorion, mod. village, 451 akc¸e, 586, 587 acorns, 228, 229, 364, 491, 626 Akindynos, Gregory, 255 Adam akinetos (k©nhtov) see dorea; ktema; ktesis Nicholas, grant recipient, xxi, 206, 481 Aklou, village, 148 official, xv, 123 Akridakes, Constantine, priest, 301 syr, kavallarios,landholder,206, 481 Akropolites, George, historian, 15, 224, 225, Adam, village, 490, 619 284, 358 adelphaton,pl.adelphata, 153 Akros see Longos Adrian Akroterion, village, 570, 572, 573 landholder in the 1320s, 400 aktemon (ktmwn), pl. aktemones, 70, 85, 86, pronoia holder prior to 1301, 520 139, 140, 141–42, 143, 144, 214, 215, Adrianople, 330, 551 590 Adriatic Sea, 603, 604 Alans, 436, 502 Aegean Sea, 502, 510, 602, 604 Albania, 4, 584 aer, aerikon see under taxes, specific Alexios I Komnenos, emperor (1081–1118), xl, agridion, xxii, 466, 540–42, 570 xlii Ahrweiler, Hel´ ene,` 7 chrysobulls of, xv, xvi, 84, 128, 129, 134, on Adrian Komnenos, 137 140, 160, 255 on Alopos, 197 and coinage, 116 on appanages, 290, 291, 292, 293 and gifts of paroikoi, 85 on charistike, 155 and imperial grants, 29, 30, 58, 66, 69,