SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS [Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparison of the Myxobolus Fauna of Common Barbel from Hungary and Iberian Barbel from Portugal

Vol. 100: 231–248, 2012 DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Published September 12 doi: 10.3354/dao02469 Dis Aquat Org Comparison of the Myxobolus fauna of common barbel from Hungary and Iberian barbel from Portugal K. Molnár1,*, E. Eszterbauer1, Sz. Marton1, Cs. Székely1, J. C. Eiras2 1Institute for Veterinary Medical Research, Centre for Agricultural Research, HAS, POB 18, 1581 Budapest, Hungary 2Departamento de Biologia, e CIIMAR, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto, Rua do Campo Alegre, s/n, Edifício FC4, 4169-007 Porto, Portugal ABSTRACT: We compared Myxobolus infection of common barbel Barbus barbus from the Danube River in Hungary with that in Iberian barbel Luciobarbus bocagei from the Este River in Portugal. In Hungary, we recorded 5 known Myxobolus species (M. branchialis, M. caudatus, M. musculi, M. squamae, and M. tauricus) and described M. branchilateralis sp. n. In Portugal we recorded 6 Myxobolus species (M. branchialis, M. branchilateralis sp. n., M. cutanei, M. musculi, M. pfeifferi, and M. tauricus). Species found in the 2 habitats had similar spore morphology and only slight differences were observed in spore shape or measurements. All species showed a spe- cific tissue tropism and had a definite site selection. M. branchialis was recorded from the lamellae of the gills, large plasmodia of M. branchilateralis sp. n. developed at both sides of hemibranchia, M. squamae infected the scales, plasmodia of M. caudatus infected the scales and the fins, and M. tauricus were found in the fins and pin bones. In the muscle, 3 species, M. musculi, M. pfeifferi and M. tauricus were found; however they were found in distinct locations. -

FIELD GUIDE to WARMWATER FISH DISEASES in CENTRAL and EASTERN EUROPE, the CAUCASUS and CENTRAL ASIA Cover Photographs: Courtesy of Kálmán Molnár and Csaba Székely

SEC/C1182 (En) FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular I SSN 2070-6065 FIELD GUIDE TO WARMWATER FISH DISEASES IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE, THE CAUCASUS AND CENTRAL ASIA Cover photographs: Courtesy of Kálmán Molnár and Csaba Székely. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular No. 1182 SEC/C1182 (En) FIELD GUIDE TO WARMWATER FISH DISEASES IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE, THE CAUCASUS AND CENTRAL ASIA By Kálmán Molnár1, Csaba Székely1 and Mária Láng2 1Institute for Veterinary Medical Research, Centre for Agricultural Research, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary 2 National Food Chain Safety Office – Veterinary Diagnostic Directorate, Budapest, Hungary FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Ankara, 2019 Required citation: Molnár, K., Székely, C. and Láng, M. 2019. Field guide to the control of warmwater fish diseases in Central and Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular No.1182. Ankara, FAO. 124 pp. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. -

FIELD GUIDE to WARMWATER FISH DISEASES in CENTRAL and EASTERN EUROPE, the CAUCASUS and CENTRAL ASIA Cover Photographs: Courtesy of Kálmán Molnár and Csaba Székely

SEC/C1182 (En) FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular I SSN 2070-6065 FIELD GUIDE TO WARMWATER FISH DISEASES IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE, THE CAUCASUS AND CENTRAL ASIA Cover photographs: Courtesy of Kálmán Molnár and Csaba Székely. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular No. 1182 SEC/C1182 (En) FIELD GUIDE TO WARMWATER FISH DISEASES IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE, THE CAUCASUS AND CENTRAL ASIA By Kálmán Molnár1, Csaba Székely1 and Mária Láng2 1Institute for Veterinary Medical Research, Centre for Agricultural Research, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary 2 National Food Chain Safety Office – Veterinary Diagnostic Directorate, Budapest, Hungary FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Ankara, 2019 Required citation: Molnár, K., Székely, C. and Láng, M. 2019. Field guide to the control of warmwater fish diseases in Central and Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular No.1182. Ankara, FAO. 124 pp. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. -

How Barriers Shape Freshwater Fish Distributions: a Species Distribution Model Approach

1 How barriers shape freshwater fish distributions: a species distribution model approach 2 3 Mathias Kuemmerlen1* [email protected] 4 Stefan Stoll1,2 [email protected] 5 Peter Haase1,3 [email protected] 6 7 1Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt, Department of River 8 Ecology and Conservation, Clamecystr. 12, D-63571 Gelnhausen, Germany 9 2University of Koblenz-Landau, Institute for Environmental Sciences, Fortstr. 7, 76829 Landau, 10 Germany 11 3University of Duisburg-Essen, Faculty of Biology, Essen, Germany 12 *Corresponding author: Tel: +49 6051-61954-3120 13 Fax: +49 6051-61954-3118 14 15 Running title: How barriers shape fish distributions 16 17 Word count main text = 4679 18 1 PeerJ Preprints | https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.2112v2 | CC BY 4.0 Open Access | rec: 18 Aug 2016, publ: 18 Aug 2016 19 Abstract 20 Aim 21 Barriers continue to be built globally despite their well-known negative effects on freshwater 22 ecosystems. Fish habitats are disturbed by barriers and the connectivity in the stream network 23 reduced. We implemented and assessed the use of barrier data, including their size and 24 magnitude, in distribution predictions for 20 species of freshwater fish to understand the 25 impacts on freshwater fish distributions. 26 27 Location 28 Central Germany 29 30 Methods 31 Obstruction metrics were calculated from barrier data in three different spatial contexts 32 relevant to fish migration and dispersal: upstream, downstream and along 10km of stream 33 network. The metrics were included in a species distribution model and compared to a model 34 without them, to reveal how barriers influence the distribution patterns of fish species. -

Folia 1/02-Def

Folia Zool. – 51(1): 55–66 (2002) Movements of barbel, Barbus barbus (Pisces: Cyprinidae) ✝ Dedicated to the late Professor Antonín Lelek - our friend and colleague Milan PE≈ÁZ, Vlastimil BARU·, Miroslav PROKE· and Miloslav HOMOLKA Institute of Vertebrate Biology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic Kvûtná 8, 603 65 Brno, Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected] Received 10 May 2001; Accepted 7 August 2001 Abstract. Altogether 701 adult barbel, Barbus barbus were captured by electrofishing and individually tagged to study their local displacement and movements in a stretch of the River Jihlava (Czech Republic). A total of 149 fish were recaptured and 105 of them (70.47 %) were considered as ”resident” because they were always recaptured in the same, relatively restricted (250 - 780 m) stream section, which always contained a pool and was demarcated naturally by riffles on both edges. The remaining 44 recaptured specimens (29.53 %) belonged to the “mobile” part of population, their movements encompassing two (or exceptionally more) adjacent stream sections and at maximum a distance of 1680 m downstream or 2020 m upstream. The proportion of mobile barbel, relatively low in smaller and middle size classes, increased in the largest size classes (451–550 mm of SL). A rather limited extent of movements also suggests a relatively small area of home range in the studied stretch, which nevertheless provides satisfactory resources and favourable conditions required by barbel over their entire life cycle. The extent of movements and corresponding proportion of mobile fish appear to be increasing with diminishing habitat patchiness. In the stretch of River Jihlava studied, with a rich patchy heterogenous habitat and well developed riffle-pool-raceway structure, each section (pool) can be considered as a more or less isolated spatial unit containing its own, and in a certain degree, isolated component of a metapopulation. -

Artificial Reproduction of Blue Bream (Ballerus Ballerus L.) As A

animals Article Artificial Reproduction of Blue Bream (Ballerus ballerus L.) as a Conservative Method under Controlled Conditions Przemysław Piech * and Roman Kujawa Department of Ichthyology and Aquaculture, Faculty of Animal Bioengineering, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, PL 10-719 Olsztyn, Poland; reofi[email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Quite severe biological imbalances have been caused by the often ill-conceived and destructive actions of humans. The natural environment, with its flora and fauna, has been subjected to a strong, direct or indirect, anthropogenic impact. In consequence, the total population of wild animals has been considerably reduced, despite efforts to compensate for these errors and expand the scope of animal legal protection to include endangered species. Many animal populations on the verge of extinction have been saved. These actions are ongoing and embrace endangered species as well as those which may be threatened with extinction in the near future as a result of climate change. The changes affect economically valuable species and those of low value, whose populations are still relatively strong and stable. Pre-emptive protective actions and developing methods for the reproduction and rearing of rare species may ensure their survival when the ecological balance is upset. The blue bream is one such species which should be protected while there is still time. Abstract: The blue bream Ballerus ballerus (L.) is one of two species of the Ballerus genus occurring in Citation: Piech, P.; Kujawa, R. Europe. The biotechnology for its reproduction under controlled conditions needs to be developed to Artificial Reproduction of Blue Bream conserve its local populations. -

History of Fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification

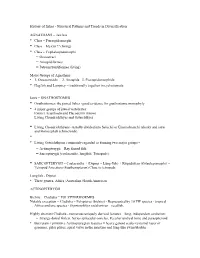

History of fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification AGNATHANS = Jawless • Class – Pteraspidomorphi • Class – Myxini?? (living) • Class – Cephalaspidomorphi – Osteostraci – Anaspidiformes – Petromyzontiformes (living) Major Groups of Agnathans • 1. Osteostracida 2. Anaspida 3. Pteraspidomorphida • Hagfish and Lamprey = traditionally together in cyclostomata Jaws = GNATHOSTOMES • Gnathostomes: the jawed fishes -good evidence for gnathostome monophyly. • 4 major groups of jawed vertebrates: Extinct Acanthodii and Placodermi (know) Living Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes • Living Chondrichthyans - usually divided into Selachii or Elasmobranchi (sharks and rays) and Holocephali (chimeroids). • • Living Osteichthyans commonly regarded as forming two major groups ‑ – Actinopterygii – Ray finned fish – Sarcopterygii (coelacanths, lungfish, Tetrapods). • SARCOPTERYGII = Coelacanths + (Dipnoi = Lung-fish) + Rhipidistian (Osteolepimorphi) = Tetrapod Ancestors (Eusthenopteron) Close to tetrapods Lungfish - Dipnoi • Three genera, Africa+Australian+South American ACTINOPTERYGII Bichirs – Cladistia = POLYPTERIFORMES Notable exception = Cladistia – Polypterus (bichirs) - Represented by 10 FW species - tropical Africa and one species - Erpetoichthys calabaricus – reedfish. Highly aberrant Cladistia - numerous uniquely derived features – long, independent evolution: – Strange dorsal finlets, Series spiracular ossicles, Peculiar urohyal bone and parasphenoid • But retain # primitive Actinopterygian features = heavy ganoid scales (external -

MULLIDAE Goatfishes by J.E

click for previous page 1654 Bony Fishes MULLIDAE Goatfishes by J.E. Randall, B.P.Bishop Museum, Hawaii, USA iagnostic characters: Small to medium-sized fishes (to 40 cm) with a moderately elongate, slightly com- Dpressed body; ventral side of head and body nearly flat. Eye near dorsal profile of head. Mouth relatively small, ventral on head, and protrusible, the upper jaw slightly protruding; teeth conical, small to very small. Chin with a pair of long sensory barbels that can be folded into a median groove on throat. Two well separated dorsal fins, the first with 7 or 8 spines, the second with 1 spine and 8 soft rays. Anal fin with 1 spine and 7 soft rays.Caudal fin forked.Paired fins of moderate size, the pectorals with 13 to 17 rays;pelvic fins with 1 spine and 5 soft rays, their origin below the pectorals. Scales large and slightly ctenoid (rough to touch); a single continuous lateral line. Colour: variable; whitish to red, with spots or stripes. 1st dorsal fin with 7or8spines 2nd dorsal fin with 1 spine and 8 soft rays pair of long sensory barbels Habitat, biology, and fisheries: Goatfishes are bottom-dwelling fishes usually found on sand or mud sub- strata, but 2 of the 4 western Atlantic species occur on coral reefs where sand is prevalent. The barbels are supplied with chemosensory organs and are used to detect prey by skimming over the substratum or by thrust- ing them into the sediment. Food consists of a wide variety of invertebrates, mostly those that live beneath the surface of the sand or mud. -

Fish Fossils As Paleo-Indicators of Ichthyofauna Composition and Climatic Change in Lake Malawi, Africa

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 303 (2011) 126–132 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Fish fossils as paleo-indicators of ichthyofauna composition and climatic change in Lake Malawi, Africa Peter N. Reinthal a,⁎, Andrew S. Cohen b, David L. Dettman b a Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA b Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA article info abstract Article history: Numerous biological and chemical paleorecords have been used to infer paleoclimate, lake level fluctuation Received 27 February 2009 and faunal composition from the drill cores obtained from Lake Malawi, Africa. However, fish fossils have Received in revised form 23 October 2009 never been used to examine changes in African Great Lake vertebrate aquatic communities nor as indicators Accepted 1 January 2010 of changing paleolimnological conditions. Here we present results of analyses of a Lake Malawi core dating Available online 7 January 2010 back ∼144 ka that describe and quantify the composition and abundance of fish fossils and report on stable carbon isotopic data (δ13C) from fish scale, bone and tooth fossils. We compared the fossil δ13C values to δ13C Keywords: fi Lake Malawi values from extant sh communities to determine whether carbon isotope ratios can be used as indicators of Cichlid inshore versus offshore pelagic fish assemblages. Fossil buccal teeth, pharyngeal teeth and mills, vertebra and Fish fossils scales from the fish families Cichlidae and Cyprinidae occur in variable abundance throughout the core. Carbon isotopes Carbon isotopic ratios from numerous fish fossils throughout the core range between −7.2 and −27.5‰, Cyprinid similar to those found in contemporary Lake Malawi benthic and pelagic fish faunas. -

1 Serena Zaccara 2 Department of Theoretical and Applied

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bournemouth University Research Online 1 Correspondence: 2 Serena Zaccara 3 Department of Theoretical and Applied Sciences, University of Insubria, Via J. H. 4 Dunant, 3 – 21100 – Varese (VA), Italy. 5 Phone: +39 0332 421422 6 E-mail: [email protected] 7 8 Morphologic and genetic variability in the Barbus fishes (Teleostei, Cyprinidae) of 9 Central Italy 10 11 12 ZACCARA SERENA1, QUADRONI SILVIA1, VANETTI ISABELLA1, CAROSI 13 ANTONELLA2, LA PORTA GIANANDREA2, CROSA GIUSEPPE1, BRITTON ROBERT 14 3, LORENZONI MASSIMO2 15 16 1Department of Theoretical and Applied Sciences, University of Insubria, Varese (VA) - 17 Italy 18 2Department of Chemistry, Biology and Biotechnology, University of Perugia, Perugia 19 (PG) - Italy 20 3Centre for Conservation Ecology and Environmental Change, Bournemouth University, 21 Poole, Dorset - UK 22 23 Running title: Barbels dispersion in central Italy 24 Zaccara et al. 25 Zaccara et al. 1 26 Zaccara, S. (2018) New patterns of morphologic and genetic variability of barbels 27 (Teleostei, Cyprinidae) in central Italy. Zoologica Scripta, 00, 000-000. 28 29 Abstract 30 31 Italian freshwaters are highly biodiverse, with species present including the native 32 fishes Barbus plebejus and Barbus tyberinus that are threatened by habitat alteration, 33 fish stocking and invasive fishes, especially European barbel Barbus barbus. In central 34 Italy, native fluvio-lacustrine barbels are mainly allopatric and so provide an excellent 35 natural system to evaluate the permeability of the Apennine Mountains. Here, the 36 morphologic and genetic distinctiveness was determined for 611 Barbus fishes collected 37 along the Padany-Venetian (Adriatic basins; PV) and Tuscany-Latium (Tyrrhenian 38 basins; TL) districts. -

Barbel Cholera, a Rare but Still Possible Food-Borne Poisoning. Case Report

Acta Biomed 2018; Vol. 89, N. 4: 590-592 DOI: 10.23750/abm.v89i4.7606 © Mattioli 1885 Emergence Medicine - Up date Barbel cholera, a rare but still possible food-borne poisoning. Case report and narrative review Ivan Comelli1, Matteo Riccò2, Gianfranco Cervellin1 1 Emergency Department, University Hospital of Parma, Parma, Italy; 2 Working Environment Prevention and Safety Service. Local Health Agency, Reggio nell’Emilia, Italy Summary. The gastro enteric toxic effects of the barbel eggs have been described up to two centuries ago, but deliberate or serendipitous ingestion of this fish product still occur, often eliciting a gastrointestinal syn- drome usually known as barbel cholera. Barbel cholera is a self-limited gastrointestinal diarrheic syndrome that develops 2 to 4 hours after ingestion of the eggs, lasting up to 12-36 hours, nearly always complicated by vomiting and severe abdominal pain. The disease is usually self-limited, and the prognosis is thus benign even without hospitalization and medical treatment. Rarely, however, barbel cholera may be complicated by mas- sive diarrhea, and the patients can develop bradycardia, oligo-anuria, and eventually hypovolemic shock. In this article we describe a rare case of barbel cholera, highlighting both the diagnostic difficulties in identifying it, and the importance of obtain an accurate history, focused on recently ingested food, thus addressing the clinical management on supportive treatment, expecting symptoms’ improvement usually within 36 hours. (www.actabiomedica.it) Key words: barbel cholera, barbus fish, barbel eggs, food borne poisoning, gastroenteritis, Emergency Depart- ment Introduction deliberate or serendipitous ingestion of barbel eggs still occur, often eliciting a gastrointestinal syndrome usu- The genus Barbus includes several species of fresh- ally known as barbel cholera (1-4). -

Fish Identification Guide Depicts More Than 50 Species of Fish Commonly Encoun- Make the Proper Identification of Every Fish Caught

he identification of different spe- Most species of fish are distinctive in appear- ance and relatively easy to identify. However, cies of fish has become an im- closely related species, such as members of the portant concern for recreational same “family” of fish, can present problems. For these species it is important to look for certain fishermen. The proliferation of T distinctive characteristics to make a positive regulations relating to minimum identification. sizes and possession limits compels fishermen to The ensuing fish identification guide depicts more than 50 species of fish commonly encoun- make the proper identification of every fish caught. tered in Virginia waters. In addition to color illustrations of each species, the description of each species lists the distinctive characteristics which enable a positive identification. Total Length FIRST DORSAL FIN Fork Length SECOND NUCHAL DORSAL FIN BAND SQUARE TAIL NARES FORKED TAIL GILL COVER (Operculum) CAUDAL LATRAL PEDUNCLE CHIN BARBELS LINE PECTORAL CAUDAL FIN ANAL FINS FIN PELVIC FINS GILL RAKERS GILL ARCH UNDERSIDE OF GILL COVER GILL RAKER GILL FILAMENTS GILL FILAMENTS DEFINITIONS Anal Fin – The fin on the bottom of fish located between GILL ARCHES 1st the anal vent (hole) and the tail. 2nd 3rd Barbels – Slender strands extending from the chins of 4th some fish (often appearing similar to whiskers) which per- form a sensory function. Caudal Fin – The tail fin of fish. Nuchal Band – A dark band extending from behind or Caudal Peduncle – The narrow portion of a fish’s body near the eye of a fish across the back of the neck toward immediately in front of the tail.