Morphological and Histological Data on the Structure of the Lingual Toothplate of Arapaima Gigas (Osteoglossidae; Teleostei)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taxonomy and Biochemical Genetics of Some African Freshwater Fish Species

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Taxonomy and biochemical genetics of some African freshwater fish species. Abban, Edward Kofi How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Abban, Edward Kofi (1988) Taxonomy and biochemical genetics of some African freshwater fish species.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa43062 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ TAXONOMY AND BIOCHEMICAL GENETICS OF SOME AFRICAN FRESHWATER FISH SPECIES. BY EDWARD KOFI ABBAN A Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. UNIVERSITY OF WALES. 1988 ProQuest Number: 10821454 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

The Cyphomyrus Myers 1960 (Osteoglossiformes: Mormyridae) of the Lufira Basin (Upper Lualaba: DR Congo): a Generic Reassignment and the Description of a New Species

Received: 9 January 2019 Accepted: 15 December 2019 DOI: 10.1111/jfb.14237 SPECIAL ISSUE REGULAR PAPER FISH The Cyphomyrus Myers 1960 (Osteoglossiformes: Mormyridae) of the Lufira basin (Upper Lualaba: DR Congo): A generic reassignment and the description of a new species Christian Mukweze Mulelenu1,2,3,4 | Bauchet Katemo Manda2,3,4 | Eva Decru3,4 | Auguste Chocha Manda2 | Emmanuel Vreven3,4 1Département de Zootechnie, Faculté des Sciences Agronomiques, Université de Abstract Kolwezi, Kolwezi, Democratic Republic of the Within a comparative morphological framework, Hippopotamyrus aelsbroecki, only Congo known from the holotype originating from Lubumbashi, most probably the Lubumbashi 2Département de Gestion des Ressources Naturelles Renouvelables, Unité de recherche River, a left bank subaffluent of the Luapula River, is reallocated to the genus en Biodiversité et Exploitation durable des Cyphomyrus. This transfer is motivated by the fact that H. aelsbroecki possesses a Zones Humides, Université de Lubumbashi, Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the rounded or vaulted predorsal profile, an insertion of the dorsal fin far anterior to the Congo level of the insertion of the anal fin, and a compact, laterally compressed and deep 3Vertebrate Section, Ichthyology, Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium body. In addition, a new species of Cyphomyrus is described from the Lufira basin, 4Laboratory of Biodiversity and Evolutionary Cyphomyrus lufirae. Cyphomyrus lufirae was collected in large parts of the Middle Lufira, Genomics, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium upstream of the Kyubo Falls and just downstream of these falls in the lower Lufira and Correspondence its nearby left bank affluent, the Luvilombo River. The new species is distinguished Emmanuel Vreven, Curator of Fishes from all its congeners, that is, firstly, from C. -

A Review of the Systematic Biology of Fossil and Living Bony-Tongue Fishes, Osteoglossomorpha (Actinopterygii: Teleostei)

Neotropical Ichthyology, 16(3): e180031, 2018 Journal homepage: www.scielo.br/ni DOI: 10.1590/1982-0224-20180031 Published online: 11 October 2018 (ISSN 1982-0224) Copyright © 2018 Sociedade Brasileira de Ictiologia Printed: 30 September 2018 (ISSN 1679-6225) Review article A review of the systematic biology of fossil and living bony-tongue fishes, Osteoglossomorpha (Actinopterygii: Teleostei) Eric J. Hilton1 and Sébastien Lavoué2,3 The bony-tongue fishes, Osteoglossomorpha, have been the focus of a great deal of morphological, systematic, and evolutio- nary study, due in part to their basal position among extant teleostean fishes. This group includes the mooneyes (Hiodontidae), knifefishes (Notopteridae), the abu (Gymnarchidae), elephantfishes (Mormyridae), arawanas and pirarucu (Osteoglossidae), and the African butterfly fish (Pantodontidae). This morphologically heterogeneous group also has a long and diverse fossil record, including taxa from all continents and both freshwater and marine deposits. The phylogenetic relationships among most extant osteoglossomorph families are widely agreed upon. However, there is still much to discover about the systematic biology of these fishes, particularly with regard to the phylogenetic affinities of several fossil taxa, within Mormyridae, and the position of Pantodon. In this paper we review the state of knowledge for osteoglossomorph fishes. We first provide an overview of the diversity of Osteoglossomorpha, and then discuss studies of the phylogeny of Osteoglossomorpha from both morphological and molecular perspectives, as well as biogeographic analyses of the group. Finally, we offer our perspectives on future needs for research on the systematic biology of Osteoglossomorpha. Keywords: Biogeography, Osteoglossidae, Paleontology, Phylogeny, Taxonomy. Os peixes da Superordem Osteoglossomorpha têm sido foco de inúmeros estudos sobre a morfologia, sistemática e evo- lução, particularmente devido à sua posição basal dentre os peixes teleósteos. -

Teleostei, Osteoglossomorpha)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 561: 117–150Cryptomyrus (2016) : a new genus of Mormyridae (Teleostei, Osteoglossomorpha)... 117 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.561.7137 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Cryptomyrus: a new genus of Mormyridae (Teleostei, Osteoglossomorpha) with two new species from Gabon, West-Central Africa John P. Sullivan1, Sébastien Lavoué2, Carl D. Hopkins1,3 1 Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, New York 14850 USA 2 Institute of Oceanography, National Taiwan University, Roosevelt Road, Taipei 10617, Taiwan 3 Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853 USA Corresponding author: John P. Sullivan ([email protected]) Academic editor: N. Bogutskaya | Received 9 November 2015 | Accepted 20 December 2015 | Published 8 February 2016 http://zoobank.org/BBDC72CD-2633-45F2-881B-49B2ECCC9FE2 Citation: Sullivan JP, Lavoué S, Hopkins CD (2016) Cryptomyrus: a new genus of Mormyridae (Teleostei, Osteoglossomorpha) with two new species from Gabon, West-Central Africa. ZooKeys 561: 117–150. doi: 10.3897/ zookeys.561.7137 Abstract We use mitochondrial and nuclear sequence data to show that three weakly electric mormyrid fish speci- mens collected at three widely separated localities in Gabon, Africa over a 13-year period represent an un- recognized lineage within the subfamily Mormyrinae and determine its phylogenetic position with respect to other taxa. We describe these three specimens as a new genus containing two new species. Cryptomyrus, new genus, is readily distinguished from all other mormyrid genera by a combination of features of squa- mation, morphometrics, and dental attributes. Cryptomyrus ogoouensis, new species, is differentiated from its single congener, Cryptomyrus ona, new species, by the possession of an anal-fin origin located well in advance of the dorsal fin, a narrow caudal peduncle and caudal-fin lobes nearly as long as the peduncle. -

History of Fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification

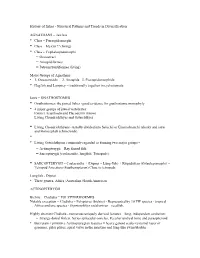

History of fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification AGNATHANS = Jawless • Class – Pteraspidomorphi • Class – Myxini?? (living) • Class – Cephalaspidomorphi – Osteostraci – Anaspidiformes – Petromyzontiformes (living) Major Groups of Agnathans • 1. Osteostracida 2. Anaspida 3. Pteraspidomorphida • Hagfish and Lamprey = traditionally together in cyclostomata Jaws = GNATHOSTOMES • Gnathostomes: the jawed fishes -good evidence for gnathostome monophyly. • 4 major groups of jawed vertebrates: Extinct Acanthodii and Placodermi (know) Living Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes • Living Chondrichthyans - usually divided into Selachii or Elasmobranchi (sharks and rays) and Holocephali (chimeroids). • • Living Osteichthyans commonly regarded as forming two major groups ‑ – Actinopterygii – Ray finned fish – Sarcopterygii (coelacanths, lungfish, Tetrapods). • SARCOPTERYGII = Coelacanths + (Dipnoi = Lung-fish) + Rhipidistian (Osteolepimorphi) = Tetrapod Ancestors (Eusthenopteron) Close to tetrapods Lungfish - Dipnoi • Three genera, Africa+Australian+South American ACTINOPTERYGII Bichirs – Cladistia = POLYPTERIFORMES Notable exception = Cladistia – Polypterus (bichirs) - Represented by 10 FW species - tropical Africa and one species - Erpetoichthys calabaricus – reedfish. Highly aberrant Cladistia - numerous uniquely derived features – long, independent evolution: – Strange dorsal finlets, Series spiracular ossicles, Peculiar urohyal bone and parasphenoid • But retain # primitive Actinopterygian features = heavy ganoid scales (external -

MULLIDAE Goatfishes by J.E

click for previous page 1654 Bony Fishes MULLIDAE Goatfishes by J.E. Randall, B.P.Bishop Museum, Hawaii, USA iagnostic characters: Small to medium-sized fishes (to 40 cm) with a moderately elongate, slightly com- Dpressed body; ventral side of head and body nearly flat. Eye near dorsal profile of head. Mouth relatively small, ventral on head, and protrusible, the upper jaw slightly protruding; teeth conical, small to very small. Chin with a pair of long sensory barbels that can be folded into a median groove on throat. Two well separated dorsal fins, the first with 7 or 8 spines, the second with 1 spine and 8 soft rays. Anal fin with 1 spine and 7 soft rays.Caudal fin forked.Paired fins of moderate size, the pectorals with 13 to 17 rays;pelvic fins with 1 spine and 5 soft rays, their origin below the pectorals. Scales large and slightly ctenoid (rough to touch); a single continuous lateral line. Colour: variable; whitish to red, with spots or stripes. 1st dorsal fin with 7or8spines 2nd dorsal fin with 1 spine and 8 soft rays pair of long sensory barbels Habitat, biology, and fisheries: Goatfishes are bottom-dwelling fishes usually found on sand or mud sub- strata, but 2 of the 4 western Atlantic species occur on coral reefs where sand is prevalent. The barbels are supplied with chemosensory organs and are used to detect prey by skimming over the substratum or by thrust- ing them into the sediment. Food consists of a wide variety of invertebrates, mostly those that live beneath the surface of the sand or mud. -

Fish Fossils As Paleo-Indicators of Ichthyofauna Composition and Climatic Change in Lake Malawi, Africa

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 303 (2011) 126–132 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Fish fossils as paleo-indicators of ichthyofauna composition and climatic change in Lake Malawi, Africa Peter N. Reinthal a,⁎, Andrew S. Cohen b, David L. Dettman b a Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA b Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA article info abstract Article history: Numerous biological and chemical paleorecords have been used to infer paleoclimate, lake level fluctuation Received 27 February 2009 and faunal composition from the drill cores obtained from Lake Malawi, Africa. However, fish fossils have Received in revised form 23 October 2009 never been used to examine changes in African Great Lake vertebrate aquatic communities nor as indicators Accepted 1 January 2010 of changing paleolimnological conditions. Here we present results of analyses of a Lake Malawi core dating Available online 7 January 2010 back ∼144 ka that describe and quantify the composition and abundance of fish fossils and report on stable carbon isotopic data (δ13C) from fish scale, bone and tooth fossils. We compared the fossil δ13C values to δ13C Keywords: fi Lake Malawi values from extant sh communities to determine whether carbon isotope ratios can be used as indicators of Cichlid inshore versus offshore pelagic fish assemblages. Fossil buccal teeth, pharyngeal teeth and mills, vertebra and Fish fossils scales from the fish families Cichlidae and Cyprinidae occur in variable abundance throughout the core. Carbon isotopes Carbon isotopic ratios from numerous fish fossils throughout the core range between −7.2 and −27.5‰, Cyprinid similar to those found in contemporary Lake Malawi benthic and pelagic fish faunas. -

Zootaxa, African Weakly Electric Fishes of the Genus Petrocephalus

TERMS OF USE This pdf is provided by Magnolia Press for private/research use. Commercial sale or deposition in a public library or website is prohibited. Zootaxa 2600: 1–52 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) African weakly electric fishes of the genus Petrocephalus (Osteoglossomorpha: Mormyridae) of Odzala National Park, Republic of the Congo (Lékoli River, Congo River basin) with description of five new species SÉBASTIEN LAVOUÉ1, JOHN P. SULLIVAN2 & MATTHEW E. ARNEGARD3 1Department of Zoology, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD, UK. E-mail: [email protected] 2Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 3Human Biology Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Ave. N., Seattle, WA 98109, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Table of contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Résumé................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Material and methods ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Copyrighted Material

06_250317 part1-3.qxd 12/13/05 7:32 PM Page 15 Phylum Chordata Chordates are placed in the superphylum Deuterostomia. The possible rela- tionships of the chordates and deuterostomes to other metazoans are dis- cussed in Halanych (2004). He restricts the taxon of deuterostomes to the chordates and their proposed immediate sister group, a taxon comprising the hemichordates, echinoderms, and the wormlike Xenoturbella. The phylum Chordata has been used by most recent workers to encompass members of the subphyla Urochordata (tunicates or sea-squirts), Cephalochordata (lancelets), and Craniata (fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals). The Cephalochordata and Craniata form a mono- phyletic group (e.g., Cameron et al., 2000; Halanych, 2004). Much disagree- ment exists concerning the interrelationships and classification of the Chordata, and the inclusion of the urochordates as sister to the cephalochor- dates and craniates is not as broadly held as the sister-group relationship of cephalochordates and craniates (Halanych, 2004). Many excitingCOPYRIGHTED fossil finds in recent years MATERIAL reveal what the first fishes may have looked like, and these finds push the fossil record of fishes back into the early Cambrian, far further back than previously known. There is still much difference of opinion on the phylogenetic position of these new Cambrian species, and many new discoveries and changes in early fish systematics may be expected over the next decade. As noted by Halanych (2004), D.-G. (D.) Shu and collaborators have discovered fossil ascidians (e.g., Cheungkongella), cephalochordate-like yunnanozoans (Haikouella and Yunnanozoon), and jaw- less craniates (Myllokunmingia, and its junior synonym Haikouichthys) over the 15 06_250317 part1-3.qxd 12/13/05 7:32 PM Page 16 16 Fishes of the World last few years that push the origins of these three major taxa at least into the Lower Cambrian (approximately 530–540 million years ago). -

A Review of the Systematic Biology of Fossil and Living Bony-Tongue Fishes, Osteoglossomorpha (Actinopterygii: Teleostei)" (2018)

W&M ScholarWorks VIMS Articles Virginia Institute of Marine Science 2018 A review of the systematic biology of fossil and living bony- tongue fishes, Osteoglossomorpha (Actinopterygii: Teleostei) Eric J. Hilton Virginia Institute of Marine Science Sebastien Lavoue Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons Recommended Citation Hilton, Eric J. and Lavoue, Sebastien, "A review of the systematic biology of fossil and living bony-tongue fishes, Osteoglossomorpha (Actinopterygii: Teleostei)" (2018). VIMS Articles. 1297. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles/1297 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in VIMS Articles by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neotropical Ichthyology, 16(3): e180031, 2018 Journal homepage: www.scielo.br/ni DOI: 10.1590/1982-0224-20180031 Published online: 11 October 2018 (ISSN 1982-0224) Copyright © 2018 Sociedade Brasileira de Ictiologia Printed: 30 September 2018 (ISSN 1679-6225) Review article A review of the systematic biology of fossil and living bony-tongue fishes, Osteoglossomorpha (Actinopterygii: Teleostei) Eric J. Hilton1 and Sébastien Lavoué2,3 The bony-tongue fishes, Osteoglossomorpha, have been the focus of a great deal of morphological, systematic, and evolutio- nary study, due in part to their basal position among extant teleostean fishes. This group includes the mooneyes (Hiodontidae), knifefishes (Notopteridae), the abu (Gymnarchidae), elephantfishes (Mormyridae), arawanas and pirarucu (Osteoglossidae), and the African butterfly fish (Pantodontidae). This morphologically heterogeneous group also has a long and diverse fossil record, including taxa from all continents and both freshwater and marine deposits. -

Fish Identification Guide Depicts More Than 50 Species of Fish Commonly Encoun- Make the Proper Identification of Every Fish Caught

he identification of different spe- Most species of fish are distinctive in appear- ance and relatively easy to identify. However, cies of fish has become an im- closely related species, such as members of the portant concern for recreational same “family” of fish, can present problems. For these species it is important to look for certain fishermen. The proliferation of T distinctive characteristics to make a positive regulations relating to minimum identification. sizes and possession limits compels fishermen to The ensuing fish identification guide depicts more than 50 species of fish commonly encoun- make the proper identification of every fish caught. tered in Virginia waters. In addition to color illustrations of each species, the description of each species lists the distinctive characteristics which enable a positive identification. Total Length FIRST DORSAL FIN Fork Length SECOND NUCHAL DORSAL FIN BAND SQUARE TAIL NARES FORKED TAIL GILL COVER (Operculum) CAUDAL LATRAL PEDUNCLE CHIN BARBELS LINE PECTORAL CAUDAL FIN ANAL FINS FIN PELVIC FINS GILL RAKERS GILL ARCH UNDERSIDE OF GILL COVER GILL RAKER GILL FILAMENTS GILL FILAMENTS DEFINITIONS Anal Fin – The fin on the bottom of fish located between GILL ARCHES 1st the anal vent (hole) and the tail. 2nd 3rd Barbels – Slender strands extending from the chins of 4th some fish (often appearing similar to whiskers) which per- form a sensory function. Caudal Fin – The tail fin of fish. Nuchal Band – A dark band extending from behind or Caudal Peduncle – The narrow portion of a fish’s body near the eye of a fish across the back of the neck toward immediately in front of the tail. -

Evo-Devo-Neuroethology of Electric Communication in Mormyrid Fishes

J. Neurogenetics, 27(3): 106–129 Copyright © 2013 Informa Healthcare USA, Inc. ISSN: 0167-7063 print/1563-5260 online DOI: 10.3109/01677063.2013.799670 Review From Sequence to Spike to Spark: Evo-devo-neuroethology of Electric Communication in Mormyrid Fishes Bruce A. Carlson 1 & Jason R. Gallant 2 1 Department of Biology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri, USA 2 Department of Biology, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts, USA Abstract: Mormyrid fi shes communicate using pulses of electricity, conveying information about their identity, behavioral state, and location. They have long been used as neuroethological model systems because they are uniquely suited to identifying cellular mechanisms for behavior. They are also remarkably diverse, and they have recently emerged as a model system for studying how communication systems may infl uence the process of speciation. These two lines of inquiry have now converged, generating insights into the neural basis of evolutionary change in behavior, as well as the infl uence of sensory and motor systems on behavioral diversifi cation and speciation. Here, we review the mechanisms of electric signal generation, reception, and analysis and relate these to our current understanding of the evolution and development of electromotor and electrosensory systems. We highlight the enormous potential of mormyrids for studying evolutionary developmental mechanisms of behavioral diversifi cation, and make the case for developing genomic and transcriptomic resources. A complete mormyrid genome sequence would enable studies that extend our understanding of mormyrid behavior to the molecular level by linking morphological and physiological mechanisms to their genetic basis. Applied in a comparative framework, genomic resources would facilitate analysis of evolutionary processes underlying mormyrid diversifi cation, reveal the genetic basis of species differences in behavior, and illuminate the origins of a novel vertebrate sensory and motor system.