Battle of Loos 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See You in Seattle

SPRING 2021 Vol. 115, No. 4 See You in Seattle The 2021 Congress Convenes Compatriot Stan Harrell donates copy of Rights of Man to SAR >>> <<< Country music star Ricky Skaggs inducted into SAR SPRING 2021 Vol. 115, No. 4 16 12 Young visitors view copy of the Rights of Man at SAR Genealogical Research Library ON THE COVER Clockwise from top left, Pike Place Market; Chihuly Garden and Glass; LeMay: America’s Car Museum; and Mount Rainier. 5 o Letters t the Editor 12 Cecil Stanford Harrell: 24 The Insurrection Act of 1807: Businessman, Patriot, A Military Perspective 6 2021AR S Congress in Renton, Philanthropist Washington 29 The “Almost Battle” 14 Daniel Boone Base Camp of Marshfield 8 A Big Year for Ricky Skaggs 250th Anniversary Series: State Society & Chapter News 9 Help Build the SAR Congress 16 30 Medals Collection The Gaspee Affair 40 In Our Memory/New Members 10 Selections from the SAR 20 Eleven Revolutions: Should Our Museum Collection Organization Be Renamed? 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. -

The Ro Y Al Regiment Sc Otl

THE ROYAL REGIMENT OF SCOTLAND (SCOTS) MARCHES, TUNES MARCHES, TUNES REGIMENT REGIMENT AND SONGS AND SONGS AL AL introduction Towards the end of the 16th Century drums and fifes became a recognised part of the military establishment. All Captains were required to have drummers and fifers in their companies. One of their duties was to ensure that all soldiers in the company recognised their company march. In Scotland the bagpipes had for centuries been the mainstay of martial music, particularly in the Highlands. Contemporary reports from the 1630’s mention a pipe band in Hepburn’s Regiment of 36 musicians and refer to “The Scottish March” believed to be the forerunner of Dumbarton’s Drums. Throughout history there are many examples of military musicians raising the morale of fighting troops at critical moments in battle. Piper George Findlater on the North West unes and Songs Frontier of Afghanistan in 1897, Bugle Major John Shaul in South Africa in 1899 and Piper Daniel Laidlaw at the battle of Loos on the Western Front in 1915, all of whom were awarded the Victoria Cross. Indeed up to the beginning of the 20th century musical instruments such as drums, bugles and bagpipes were used to pass commands and orders during battle. Soldiers have a rich history of writing and singing songs to raise morale and to foster a unit identity distinct from other regiments. This publication is intended to list those marches, tunes, calls and songs relevant to the battalions of The Royal Regiment of Scotland. It also lays down the routine and ceremonial dress worn by pipers, drummers and bandsmen of Pipes and Drums and Military Bands within the Regiment. -

Sergeant Piper to Corporal for His Distinguished Film Guns of Loos and in 1934 He Also Daniel Laidlaw SERGEANT PIPER Pictured in Service in the Field

LORD ASHCROFT'SSergeant "HERO Piper OF Daniel THE Laidlaw MONTH" VC SergeantLORD ASHCROFT'S Piper Daniel Laidlaw "HERO VC OF THE MONTH" On the very day of his some eight years. In 1929, however, LEFT: bravery, Laidlaw was promoted he re-enacted his VC action for the Sergeant Piper to corporal for his distinguished film Guns of Loos and in 1934 he also Daniel Laidlaw SERGEANT PIPER pictured in service in the field. Sadly, the took part in the film Forgotten Men. action during equally inspirational Second By now, Laidlaw was affectionately the opening day Lieutenant Young, who had known as the ‘Piper of Loos’ – or of the Battle of been severely wounded in the sometimes just ‘The Piper’. For a time, Loos. (HISTORIC fighting but who insisted on Laidlaw worked as a chicken farmer MILITARY PRESS) walking to the dressing station and, from 1938, as sub postmaster rather than being stretchered at Shoresdean, near Berwick-upon- DANIEL there, died from loss of blood. Tweed. After the outbreak of the Over their three days of fighting Second World War, his son, Victor BELOW: LORD ASHCROFT'S until 27 September, the 7th joined the KOSB in 1940, aged 20. When news "HERO OF Battalion suffered 656 casualties Laidlaw died at his home in Shoresdean of Laidlaw’s THE MONTH" (dead and wounded). on 2 June 1950, aged 74. Hundreds VC actions VC Laidlaw’s VC was announced of mourners attended his funeral. became public LAIDLAW on 18 November 1915 when Memorials in his honour include a knowledge, they became, perhaps his citation detailed how he plaque on a wall at St Cuthbert’s Church, unsurprisingly, had ‘played his company out Norham, the venue for his funeral. -

Scottish Victoria Cross Awards Corporal William Anderson, VC, 2Nd Battalion, Yorkshire Regiment, Was Born at Dallas, Elgin on 28

Scottish Victoria Cross Awards Corporal William Anderson, VC, 2nd Battalion, Yorkshire Regiment, was born at Dallas, Elgin on 28 December 1882. He was the second son of Alexander Anderson, a Labourer, and Isabella (Bella) Anderson, of 79 North Road, Forres, where he was educated at Forres Academy. His siblings were James, Margaret and Alexander. After working as a Conductor at Glasgow Tramways Depot, he moved to London then enlisted in the 2nd Battalion, Yorkshire Regiment on 20 September 1905, serving in India, Egypt and South Africa. His brother, James, served in the same regiment. He was discharged to the Reserve in 1912 and worked at Elder Hospital, Govan, saving money so that he and his fiancee could emigrate to South Africa. However, before they could leave war broke out and he was called up as a reservist. He was mobilised and sent to his old battalion in 1914, where he was known as 'Jock'. Now a Corporal, on 5 October 1914, he embarked for Flanders with the four Companies of the 2nd Battalion. Two weeks later they were taking part in the First Battle of Ypres and involved in some of the fiercest fighting. The regiment was being supplied with 96,000 rounds of ammunition each night. By the end of this engagement Corporal Anderson was in charge of a bombing unit. The aim of a bombing unit was to gain access to an enemy trench, from which they would throw grenades round a corner, immediately following up the explosion with an attack with bayoneting, Captain Rollo and Corporal Anderson bludgeoning, shooting, bombing or taking resting at Fleurbaix in 1914. -

Scottish Victoria Cross Awards Corporal William Anderson, VC, 2Nd Battalion, Yorkshire Regiment, Was Born at Dallas, Elgin on 28

Scottish Victoria Cross Awards Corporal William Anderson, VC, 2nd Battalion, Yorkshire Regiment, was born at Dallas, Elgin on 28 December 1882. He was the second son of Alexander Anderson, a Labourer, and Isabella (Bella) Anderson, of 79 North Road, Forres, where he was educated at Forres Academy. His siblings were James, Margaret and Alexander. After working as a Conductor at Glasgow Tramways Depot, he moved to London then enlisted in the 2nd Battalion, Yorkshire Regiment on 20 September 1905, serving in India, Egypt and South Africa. His brother, James, served in the same regiment. He was discharged to the Reserve in 1912 and worked at Elder Hospital, Govan, saving money so that he and his fiancee could emigrate to South Africa. However, before they could leave war broke out and he was called up as a reservist. He was mobilised and sent to his old battalion in 1914, where he was known as 'Jock'. Now a Corporal, on 5 October 1914, he embarked for Flanders with the four Companies of the 2nd Battalion. Two weeks later they were taking part in the First Battle of Ypres and involved in some of the fiercest fighting. The regiment was being supplied with 96,000 rounds of ammunition each night. By the end of this engagement Corporal Anderson was in charge of a bombing unit. The aim of a bombing unit was to gain access to an enemy trench, from which they would throw grenades round a corner, immediately following up the explosion with an attack with bayoneting, Captain Rollo and Corporal Anderson bludgeoning, shooting, bombing or taking resting at Fleurbaix in 1914. -

The Scottish Pipe Band in North America: Tradition, Transformation, and Transnational Identity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2015 The Scottish Pipe Band in North America: Tradition, Transformation, and Transnational Identity Erin F. Walker University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Walker, Erin F., "The Scottish Pipe Band in North America: Tradition, Transformation, and Transnational Identity" (2015). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 45. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/45 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

T. Grey Piper Laidlaw

PIPER LAIDLAW, VC – POEM BY THOMAS GREY, 1915 REFERENCE: BERWICK ADVERTISER, 3 DECEMBER 1915 | SUGGESTED AGE GROUPS: KS2, KS3, KS4, LIFELONG LEARNERS |TOPIC AREAS: WW1 POETRY Thomas Grey was born in Shoreswood, near Berwick in 1863. He worked for North Eastern Railways as a train driver for many years. In his 40s he was forced to find other work due to ill health. In 1918 he started working for the Post Office, but left that job, too, because of illness. Thomas seems to have written poetry all of his adult life. In 1906 he published a book of poems called Musings on the Footplate (the footplate is part of a steam engine that the driver stands on while driving the train.) It was the only book that he published during his lifetime, but the Berwick Advertiser regularly published his poems in the newspaper. During the First World War Thomas was too old to fight, but three of his sons served in the armed forces. He often wrote about events during the war. After the war, he was part of the committee that put up the war memorial in Tweedmouth. More about his life and poetry can be found by following the link below. PIPER LAIDLAW Daniel Laidlaw served with the King’s Own Scottish Borderers Regiment (KOSB) during the First World War. Although he was born in Scotland (Little Swinton), Daniel’s home was in Doddington, Northumberland. Music was very important to the British Army. Bugles were often used to signal instructions to soldiers on the battlefield and regimental bands provided rhythms for marching, to raise morale and to help build a feeling of regimental pride. -

The Royal Regiment of Scotland a Soldier's Handbook

The Royal Regiment of Scotland SCOTS A Soldier’s Handbook Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second Colonel in Chief The Royal Regiment of Scotland Contents Section Page Introduction 3 The Structure of the Regiment 3 Uniform 7 Regimental Miscellany 12 History Part One 19 History Part Two 25 History Part Three 30 Victoria Crosses 36 Values and Standards of the British Army 40 List of Illustrations Colour Sergeant on Parade Cover The Colonel in Chief 1 Regimental Headquarters 3 On Patrol in Afghanistan 4 Training in Belize, Central America 5 Afghanistan 2006 6 Capbadge and Tactical Recognition Flash 7 Hackles 8 Number 1 Dress Ceremonial 9 Jocks in Action 11 The Military Band 12 Remembrance Day Baghdad 13 Piper in Iraq 14 Air Assault 15 The Golden Lions Scottish Infantry Parachute Display Team 16 The Regimental Kirk 17 Regimental Family Tree 18 A Soldier of Hepburn’s Regiment 1633 19 A Grenadier of Hepburn’s Regiment at Tangier 1680 20 Crawford’s Highlanders at Fontenoy 21 Battle of Ticonderoga 21 Battle of Minden 22 The Duke of Wellington 23 The Duchess of Gordon 24 Piper Kenneth Mackay 25 The Troopship Birkenhead 26 The Thin Red Line 27 William McBean VC 28 Winston Churchill 30 Robert McBeath VC 31 Dennis Donnini VC 32 William Speakman VC 33 Armoured Infantry in Iraq 35 Regimental Capbadge Back Cover 2 The Royal Regiment of Scotland INTRODUCTION The Royal Regiment of Scotland is Scotland’s Infantry Regiment. Structured, equipped and manned for the 21st Century, we are fiercely proud of our heritage. Scotland has a tradition of producing courageous, resilient, tenacious and tough, infantry soldiers of world renown. -

Tions and Terms of Use PREFACE

Conditions and Terms of Use PREFACE Copyright © Heritage History 2009 The Great War has brought forth many golden deeds of Some rights reserved individual bravery, and some of the more representative and popular exploits are gathered together in the following pages. This text was produced and distributed by Heritage History, an organization While it would not be fair to characterize them as the bravest dedicated to the preservation of classical juvenile history books, and to the deeds, yet we may well rank them as among the finest examples promotion of the works of traditional history authors. of personal courage, devotion to duty, and self-sacrificing The books which Heritage History republishes are in the public domain and service that the war has produced. That all who read the are no longer protected by the original copyright. They may therefore be reproduced following pages may be thrilled with a deeper sense of the within the United States without paying a royalty to the author. matchless heroism displayed on land and sea and in air by the men of our breed, and be stimulated to better lives and worthier The text and pictures used to produce this version of the work, however, are the property of Heritage History and are licensed to individual users with some service, is the object of the writer. He has aimed at telling in restrictions. These restrictions are imposed for the purpose of protecting the integrity these simple, straightforward chapters the undying stories of the of the work itself, for preventing plagiarism, and for helping to assure that heroes who have won the Victoria Cross in the Great War, and compromised or incomplete versions of the work are not widely disseminated. -

Simon Machin

DOCTORAL THESIS Ripping Yarns The Breaking of Masculine Codes in "Boy’s Own" Adventure Stories, 1855 - 1940 Machin, Simon Award date: 2016 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Ripping Yarns: The Breaking of Masculine Codes in “Boy’s Own” Adventure Stories, 1855 – 1940 Quicquid agunt pueri nostri farrago libelli Whatever boys do makes up the mix of our little book by Simon Machin A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of English and Creative Writing Roehampton University 2016 1 Abstract My thesis explores the yarn, the British masculine adventure story for boys of all ages, from 1855 until 1940. Using Raymond Williams’ concept, “structure of feeling”, the “boy’s own” ethos is examined within its material culture, strongly influenced by the public schools. The thesis follows the yarn’s mutations in popular literature from school story to maritime adventure, colonial encounter, domestic landscape fantasy, invasion scare novel and war memoir. -

Scottish Victoria Cross Awards Corporal William Anderson, VC

Scottish Victoria Cross Awards Corporal William Anderson, VC, 2nd Battalion, Yorkshire Regiment, was born at Dallas, Elgin on 28 December 1882. He was the second son of Alexander Anderson, a Labourer, and Isabella (Bella) Anderson, of 79 North Road, Forres, where he was educated at Forres Academy. His siblings were James, Margaret and Alexander. After working as a Conductor at Glasgow Tramways Depot, he moved to London then enlisted in the 2nd Battalion, Yorkshire Regiment on 20 September 1905, serving in India, Egypt and South Africa. His brother, James, served in the same regiment. He was discharged to the Reserve in 1912 and worked at Elder Hospital, Govan, saving money so that he and his fiancee could emigrate to South Africa. However, before they could leave war broke out and he was called up as a reservist. He was mobilised and sent to his old battalion in 1914, where he was known as 'Jock'. Now a Corporal, on 5 October 1914, he embarked for Flanders with the four Companies of the 2nd Battalion. Two weeks later they were taking part in the First Battle of Ypres and involved in some of the fiercest fighting. The regiment was being supplied with 96,000 rounds of ammunition each night. By the end of this engagement Corporal Anderson was in charge of a bombing unit. The aim of a bombing unit was to gain access to an enemy trench, from which they would throw grenades round a corner, immediately following up the explosion with an attack with bayoneting, Captain Rollo and Corporal Anderson bludgeoning, shooting, bombing or taking resting at Fleurbaix in 1914. -

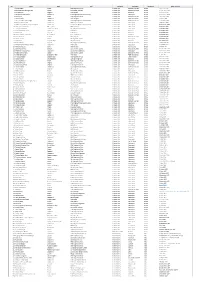

Nr1 Name Rank Unit Campaign Campaign. Campaign.. Date Of

Nr1 Name Rank Unit Campaign Campaign. Campaign.. Date of action 1 Thomas Beach Private 55th Regiment of Foot Crimean War Battle of Inkerman Crimea 5 November 1854 2 Edward William Derrington Bell Captain Royal Welch Fusiliers Crimean War Battle of the Alma Crimea 20 September 1854 3 John Berryman Sergeant 17th Lancers Crimean War Balaclava Crimea 25 October 1854 4 Claude Thomas Bourchier Lieutenant Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own) Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 20 November 1854 5 John Byrne Private 68th Regiment of Foot Crimean War Battle of Inkerman Crimea 5 November 1854 6 John Bythesea Lieutenant HMS Arrogant Crimean War Ã…land Islands Finland 9 August 1854 7 The Hon. Clifford Henry Hugh Lieutenant Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own) Crimean War Battle of Inkerman Crimea 5 November 1854 8 John Augustus Conolly Lieutenant 49th Regiment of Foot Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 26 October 1854 9 William James Montgomery Cuninghame Lieutenant Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own) Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 20 November 1854 10 Edward St. John Daniel Midshipman HMS Diamond Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 18 October 1854 11 Collingwood Dickson Lieutenant-Colonel Royal Regiment of Artillery Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 17 October 1854 12 Alexander Roberts Dunn Lieutenant 11th Hussars Crimean War Balaclava Crimea 25 October 1854 13 John Farrell Sergeant 17th Lancers Crimean War Balaclava Crimea 25 October 1854 14 Gerald Littlehales Goodlake Brevet Major Coldstream Guards Crimean War Inkerman Crimea 28 October 1854 15 James Gorman Seaman