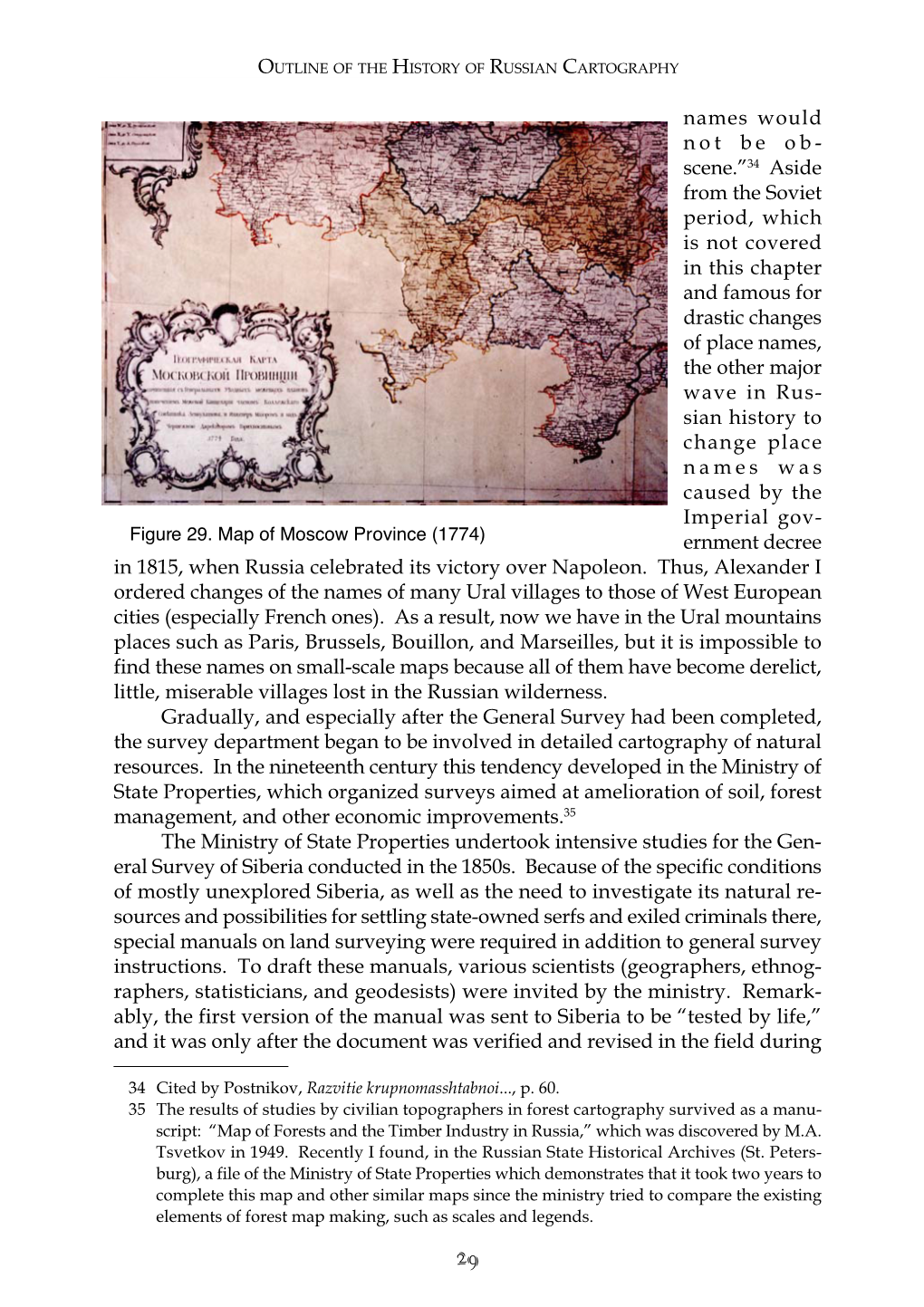

34 Aside from the Soviet Period, Which Is Not Covered in This Chapter And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Timeline for Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge

Historical Timeline Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge Much of the refuge has been protected as a national wildlife refuge for over a century, and we recognize that refuge lands are the ancestral homelands of Alaska Native people. Development of sophisticated tools and the abundance of coastal and marine wildlife have made it possible for people to thrive here for thousands of years. So many facets of Alaska’s history happened on the lands and waters of the Alaska Maritime Refuge that the Refuge seems like a time-capsule story of the state and the conservation of island wildlife: • Pre 1800s – The first people come to the islands, the Russian voyages of discovery, the beginnings of the fur trade, first rats and fox introduced to islands, Steller sea cow goes extinct. • 1800s – Whaling, America buys Alaska, growth of the fox fur industry, beginnings of the refuge. • 1900 to 1945 – Wildlife Refuge System is born and more land put in the refuge, wildlife protection increases through treaties and legislation, World War II rolls over the refuge, rats and foxes spread to more islands. The Aleutian Islands WWII National Monument designation recognizes some of these significant events and places. • 1945 to the present – Cold War bases built on refuge, nuclear bombs on Amchitka, refuge expands and protections increase, Aleutian goose brought back from near extinction, marine mammals in trouble. Refuge History - Pre - 1800 A World without People Volcanoes push up from the sea. Ocean levels fluctuate. Animals arrive and adapt to dynamic marine conditions as they find niches along the forming continent’s miles of coastline. -

Surname Distributions, Origins, and Their Association with Y-Chromosome Markers in the Aleutian Archipelago

Surname Distributions, Origins, and their Association with Y-chromosome Markers in the Aleutian Archipelago By Copyright 2010 Orion Mark Graf Submitted to the Graduate Program in Anthropology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts Dr. Michael H. Crawford (Chairperson) Dr. James H. Mielke Committee members Dr. Bartholomew C. Dean Date defended: July 12th, 2010 The Thesis Committee for Orion Mark Graf certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Surname Distributions, Origins, and their Association with Y-chromosome Markers in the Aleutian Archipelago Committee: Dr. Michael H. Crawford (Chairperson) Dr. James H. Mielke Dr. Bartholomew C. Dean Date accepted: July 12th, 2010 ii Abstract This study is an examination of the geographic distribution and ethnic origins of surnames as well as their association with Y-chromosome haplogroups found in Native communities from the Aleutian Archipelago. The project’s underlying hypothesis is that surnames and Y-chromosome haplogroups are correlated in the Aleutian Islands because both are paternally inherited markers. Using 732 surnames, Lasker’s Coefficient of relationship through isonymy (Rib) was used to identify correlations between each community based on of surnames. A subsample of 143 surnames previously characterized using Y-chromosome markers were used to directly contrast the two markers using frequency distributions and tests. Overall, it was observed that the distribution of surnames in the Aleutian Archipelago is culturally driven, rather than one of paternal inheritance. Surnames follow a gradient from east to west, with high frequencies of Russian surnames found in western Aleut communities and high levels of non- Russian surnames found in eastern Aleut communities. -

Geopolitics and Environment in the Sea Otter Trade

UC Merced UC Merced Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Soft gold and the Pacific frontier: geopolitics and environment in the sea otter trade Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/03g4f31t Author Ravalli, Richard John Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 1 Introduction Covering over one-third of the earth‘s surface, the Pacific Basin is one of the richest natural settings known to man. As the globe‘s largest and deepest body of water, it stretches roughly ten thousand miles north to south from the Bering Straight to the Antarctic Circle. Much of its continental rim from Asia to the Americas is marked by coastal mountains and active volcanoes. The Pacific Basin is home to over twenty-five thousand islands, various oceanic temperatures, and a rich assortment of plants and animals. Its human environment over time has produced an influential civilizations stretching from Southeast Asia to the Pre-Columbian Americas.1 An international agreement currently divides the Pacific at the Diomede Islands in the Bering Strait between Russia to the west and the United States to the east. This territorial demarcation symbolizes a broad array of contests and resolutions that have marked the region‘s modern history. Scholars of Pacific history often emphasize the lure of natural bounty for many of the first non-natives who ventured to Pacific waters. In particular, hunting and trading for fur bearing mammals receives a significant amount of attention, perhaps no species receiving more than the sea otter—originally distributed along the coast from northern Japan, the Kuril Islands and the Kamchatka peninsula, east toward the Aleutian Islands and the Alaskan coastline, and south to Baja California. -

Bering's Voyages Whither And

REVIEWS 87 place does the story of the death of Toni Kurz Dr. Fisher is Professor Emeritus of History on the Eiger have in a book about Canada’s at the University of California at Los Angeles, mountains?) author of TheRussian Fur Trade,1550-1770 The photographs are beautiful in this book (University of California Press, 1943), several and it will certainly be appreciated by anyone articles having to do with the settlement and who is interested in the mountains. It is a great exploration of Siberia and northwest America, book to pick up and leaf through, but it could and a guide to the records of the have been so much more. Russian-American Company heldin the Jon W. Jones National Archives of the United States. His years of study have resulted in a publication whichwill require rethinking of many BERING’S VOYAGES WHITHER AND previously held opinions about attitudes of the WHY; RAYMOND H. FISHER;Universiry of Russian government toward exploration and Washington Press; Seattle and London; 1978; 217 settlement on the North American continent. xii pp.. maps,appendices, bibliography, index; It is disappointing that the care which the $17.95. author devoted to his scholarship is not evidenced in the printing of Bering’s Voyages, On June 4, 1741, Captain Vitus Bering in St. for this reviewer’s copy, at least, was marred Peter and Captain Aleksei Chirikov in St. Paul by having pages 180,181, 184 and 185 blank. sailed east from the Kamchatka port of This destroys the usefulness of Appendix I Avatcha. The ships became separated, but by (Bering’s Account of His First Voyage) and the time Chirikov had returned to Kamchatka Appendix I1 (Kirilov’s Memorandum on the in St. -

A Case Study of the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library Rare Books Collection

Rare books as historical objects: a case study of the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library rare books collection Item Type Thesis Authors Korotkova, Ulyana Aleksandrovna; Короткова, Ульяна Александровна Download date 10/10/2021 16:12:34 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/6625 RARE BOOKS AS HISTORICAL OBJECTS: A CASE STUDY OF THE ELMER E. RASMUSON LIBRARY RARE BOOKS COLLECTION By Ulyana Korotkova RECOMMENDED: Dr. Terrence M. Cole Dr. Katherine L. Arndt Dr. M ary^R^hrlander Advisory Committee Chair Dr. Mary^E/Ehrlander Director, Arctic and Northern Studies Program RARE BOOKS AS HISTORICAL OBJECTS: A CASE STUDY OF THE ELMER E. RASMUSON LIBRARY RARE BOOKS COLLECTION A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Ulyana Korotkova Fairbanks, AK May 2016 Abstract Once upon a time all the books in the Arctic were rare books, incomparable treasures to the men and women who carried them around the world. Few of these tangible remnants of the past have managed to survive the ravages of time, preserved in libraries and special collections. This thesis analyzes the over 22,000-item rare book collection of the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the largest collection of rare books in the State of Alaska and one of the largest polar regions collections in the world. Content, chronology, authorship, design, and relevance to northern and polar history were a few of the criteria used to evaluate the collection. Twenty items of particular value to the study of Alaskan history were selected and studied in depth. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

NAVIGATING THE ‘DRUNKEN REPUBLIC’: THE JUNO AND THE RUSSIAN AMERICAN FRONTIER, 1799-1811 By TOBIN JEREL SHOREY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 © 2014 Tobin Jerel Shorey To my family, friends, and faculty mentors ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my parents and family, whose love and dedication to my education made this possible. I would also like to thank my wife, Christy, for the support and encouragement she has given me. In addition, I would like to extend my appreciation to my friends, who provided editorial comments and inspiration. To my colleagues Rachel Rothstein and Lisa Booth, thank you for all the lunches, discussions, and commiseration. This work would not have been possible without the support of all of the faculty members I have had the pleasure to work with over the years. I also appreciate the efforts of my PhD committee members in making this dream a reality: Stuart Finkel, Alice Freifeld, Peter Bergmann, Matthew Jacobs, and James Goodwin. Finally, I would like to thank the University of Florida for the opportunities I have been afforded to complete my education. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 4 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 8 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................... -

Khlebnikov's Unpublished Notes on Pharmacology

19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450 ■ 707.847.3437 ■ [email protected] ■ www.fortross.org Title: Khlebnikov’s Unpublished Notes on Pharmacology Author(s): By Kirill Khlebnikov Source: Fort Ross Conservancy Library URL: http://www.fortross.org/lib.html Unless otherwise noted in the manuscript, each author maintains copyright of his or her written material. Fort Ross Conservancy (FRC) asks that you acknowledge FRC as the distributor of the content; if you use material from FRC’s online library, we request that you link directly to the URL provided. If you use the content offline, we ask that you credit the source as follows: “Digital content courtesy of Fort Ross Conservancy, www.fortross.org; author maintains copyright of his or her written material.” Also please consider becoming a member of Fort Ross Conservancy to ensure our work of promoting and protecting Fort Ross continues: http://www.fortross.org/join.htm. This online repository is brought to you by Fort Ross Conservancy, a 501(c)(3) and California State Park cooperating association. FRC’s mission is to connect people to the history and beauty of Fort Ross and Salt Point State Parks. Khlebnikov’s Unpublished Notes on Pharmacology Introduction The Russian expansion into North America, which began in 1741 with the discovery of Alaska by navigators Vitus Bering and Aleksei Chirikov, was challenging for a number of reasons, especially by the lack of adequate healthcare services at the time. Numerous communicable diseases such as measles, smallpox, and a plethora of sexually transmitted diseases, substantially decreased the life expectancy of early settlers. -

Information to Users

Spanish Exploration In The North Pacific And Its Effect On Alaska Place Names Item Type Thesis Authors Luna, Albert Gregory Download date 05/10/2021 11:44:10 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/8541 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6* x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Journal of Northwest Anthropology

ISSN 1538-2834 JOURNAL OF NORTHWEST ANTHROPOLOGY Experiences in the University of Washington Anthropology Department, 1955–1991 Simon Ottenberg ................................................................................................... 1 The Undervalued Black Katy Chitons (Katharina Tunicata) as a Shellfish Resource on the Northwest Coast of North America Dale R. Croes ........................................................................................................ 13 Incised Stones from Idaho Jan Snedden Kee and Mark G. Plew .................................................................... 27 A Partial Stratigraphy of the Snakelum Point Site, 45-IS-13, Island County, Washington, and Comment on the Sampling of Shell Midden Sites Using Small Excavation Units Lance K. Wollwage, Guy L. Tasa, and Stephenie Kramer ................................. 43 Big Dog/Little Horse—Ethnohistorical and Linguistic Evidence for the Changing Role of Dogs on the Middle and Lower Columbia in the Nineteenth Century Cheryl A. Mack .................................................................................................... 61 Smallpox, Aleuts, and Kayaks: A Translation of Eduard Blashke’s Article on his Trip through the Aleutian Islands in 1838 Richard L. Bland .................................................................................................. 71 The 66th Annual Northwest Anthropological Conference, Portland, Oregon, 27–30 March 2013 ...................................................................................... -

Carvana Dominates Public Comment Discussion in Select Board

The Westfield NewsSearch for The Westfield News Westfield350.com The WestfieldNews Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns “TIME IS THE ONLY WEATHER CRITIC WITHOUT TONIGHT AMBITION.” Partly Cloudy. JOHN STEINBECK Low of 55. www.thewestfieldnews.com VOL. 86 NO. 151 $1.00 THURSDAY,TUESDAY, JUNEJULY 27, 15, 2017 2021 VOL. 75 cents 90 NO. 166 Carvana dominates public comment discussion in Select Board, Little League Planning Board Westfield Little League Baseball 10-Year-Old All-Stars’s Andrew Almeida Leadoff pitcher Dylan Rozell (77) on the By PETER CURRIER Staff Writer (14) makes the tag at third base. See story and photos Page 6.. (MARC mound. (MARC ST.ONGE/THE WESTFIELD ST.ONGE/THE WESTFIELD NEWS) NEWS) SOUTHWICK — Carvana dominated public comment in both the Select Board and Planning Board meetings July 12 and 13 as the July 20 public hearing drew nearer. Though Carvana was not on the agenda in either meeting, comments and questions from residents in the public comment period of both meetings were overwhelmingly related to Carvana. Council convenes for final Resident James Wong said during the July 12 Planning Board meeting that he was concerned that Carvana would fail and leave Southwick with a vacant 65.7 acre asphalt lot. vote on ordinance changes “The market for used cars is high, but it is going to crash very quickly, based on the fact that they are going to have a By AMY PORTER and Building departments that had appealed to the ZBA. shortage in car supply manufacturing,” said Wong, “So Staff Writer couldn’t enforce the zoning She said the appeal was Carvana may not even be a viable business in three years.” WESTFIELD – Ward 6 law as currently defined. -

Landrum Wayside Sits on the 42Nd Parallel, the California-Oregon Border, Which Once Divided Mexico from the Oregon Territory

A timeline of events directly concerning the Oregon-California boundary at the 42nd Parallel. Spain, Portugal, Great Britain, Russia, and New Spain (Mexico) all claimed lands that are now part of the United States of America. The Landrum Wayside sits on the 42nd Parallel, the California-Oregon border, which once divided Mexico from the Oregon Territory. The Wayside was dedicated on July 4, 1996, and flies the flags of these nations to honor the history of our region. 1492 Columbus lands in the New World, claims it for Spain and inaugurates a European rivalry for territory. 1493 Pope Alexander VI’s Papal Bull of May 4, 1493, grants Spain the right to colonize the western coast of America. It granted to the Catholic Monarchs and the heirs of the Crown of Castile exclusively all lands to the “west and south” of a pole-to-pole line 100 leagues west and south of any islands of the Azores or Cape Verde Islands. 1494 June 7th Treaty of Tordesillas establishes a meridian; Spain get what’s west of the meridian and Portugal get what’s east. 1513 Vasco Nunex de Balboa claims the “South Sea” (Pacific Ocean) and the adjoining land for the Spanish Crown. 1519 Hernando Cortez takes 11 ships with 600 men to Mexico with guns, armor and horses and conquers Montezuma II, Aztec Emperor, the capital city of Tenochitian and all of Mexico. 1521 New Spain is established following the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. 1542 Juan Rodrigues Cabrillo, a Portuguese sailing for the Spanish Crown, is the first European to explore the west coast of North America. -

Digging for the Gold - the History of the Pacific Coast and the Yukon in Images

Digging for the gold - The history of the Pacific Coast and the Yukon in images Exhibition display revised November 1 25, 2009 • In March 2002, Library and Archives Canada acquired more than 4,000 works of art from one private collector—Mr. Peter Winkworth. This acquisition is one of the largest ever made by the Government of Canada; it is certainly the largest single purchase ever undertaken on behalf of Library and Archives Canada. • Born in Montréal in 1929, Peter Winkworth began working in England in the late 1940s. He developed a passion for the visual history of Canada, and began a hunt for these images throughout Canada, the United States and Europe. Over five decades, he built an extensive and impressive collection of paintings, watercolours, drawings and prints by many of Canada’s well-known artists—works known to many curators and historians, but seen by few. Exhibition display revised November 2 25, 2009 • In keeping with the Library and Archives Canada mandate of providing access to our national treasures, the Winkworth acquisition is being presented to Canadians through a series of five regional exhibitions. A virtual exhibition of part of the collection is also available for viewing online at www.collectionscanada.ca . • Library and Archives Canada is proud to present the Peter Winkworth Collection of Canadiana exhibitions. We hope you enjoy these selections for their informative value, their aesthetic appeal, their quality of execution, and more—for their unique perspective on Canada’s past. Exhibition display revised November 3 25, 2009 Section I: Conflict and Commerce Many battles were fought in British Columbia and the Yukon: between various Aboriginal peoples; between competing European powers seeking the riches of the fur trade; and finally, between the British Empire and the American Republic.