Mountain Goat Steeve D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extinction of Harrington's Mountain Goat (Vertebrate Paleontology/Radiocarbon/Grand Canyon) JIM I

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 83, pp. 836-839, February 1986 Geology Extinction of Harrington's mountain goat (vertebrate paleontology/radiocarbon/Grand Canyon) JIM I. MEAD*, PAUL S. MARTINt, ROBERT C. EULERt, AUSTIN LONGt, A. J. T. JULL§, LAURENCE J. TOOLIN§, DOUGLAS J. DONAHUE§, AND T. W. LINICK§ *Department of Geology, Northern Arizona University, and Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff, AZ 86011; tDepartment of Geosciences and tArizona State Museum and Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721; §National Science Foundation Accelerator Facility for Radioisotope Analysis, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721 Communicated by Edward S. Deevey, Jr., October 7, 1985 ABSTRACT Keratinous horn sheaths of the extinct Har- rington's mountain goat, Oreamnos harringtoni, were recov- ered at or near the surface of dry caves of the Grand Canyon, Arizona. Twenty-three separate specimens from two caves were dated nondestructively by the tandem accelerator mass spectrometer (TAMS). Both the TAMS and the conventional dates indicate that Harrington's mountain goat occupied the Grand Canyon for at least 19,000 years prior to becoming extinct by 11,160 + 125 radiocarbon years before present. The youngest average radiocarbon dates on Shasta ground sloths, Nothrotheriops shastensis, from the region are not significantly younger than those on extinct mountain goats. Rather than sequential extinction with Harrington's mountain goat disap- pearing from the Grand Canyon before the ground sloths, as one might predict in view ofevidence ofclimatic warming at the time, the losses were concurrent. Both extinctions coincide with the regional arrival of Clovis hunters. Certain dry caves of arid America have yielded unusual perishable remains of extinct Pleistocene animals, such as hair, dung, and soft tissue of extinct ground sloths (1) and, recently, ofmammoths (2). -

Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-01-25 Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores Borkovic, Benjamin Borkovic, B. (2013). Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26635 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/498 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores by Benjamin Borkovic A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2013 © Benjamin Borkovic 2013 Abstract Evidence for sexual dimorphism was investigated in the horncores of two ceratopsid dinosaurs, Triceratops and Centrosaurus apertus. A review of studies of sexual dimorphism in the vertebrate fossil record revealed methods that were selected for use in ceratopsids. Mountain goats, bison, and pronghorn were selected as exemplar taxa for a proof of principle study that tested the selected methods, and informed and guided the investigation of sexual dimorphism in dinosaurs. Skulls of these exemplar taxa were measured in museum collections, and methods of analysing morphological variation were tested for their ability to demonstrate sexual dimorphism in their horns and horncores. -

Mountain Goat

A publication by: NORTHWEST WILDLIFE PRESERVATION SOCIETY Mountain Goat Oreamnos americanus By Errin Armstrong The mountain goat is a hoofed, even-toed mammal of the order Artiodactyla, which includes species such as cattle, deer, antelope, camels, sheep, giraffes, and hippopotamuses. While not a true goat, it is goat-like in appearance and it is the only North American representative of a tribe whose ancestry can be traced to old world European sheep and goats. It is a prevalent species in British Columbia and can often be seen along roadsides within the Rocky Mountains. Characteristics The mountain goat is a striking and unique-looking animal. It has a pure white coat ending in long hairs on the legs, which gives it the appearance of wearing shaggy pants. A crest of long hair runs from the neck and shoulders along the spine to the rump and ends in a short tail. The mountain goat’s coat is made up of a dense undercoat which is about 5cm (2 inches) in length and coarse outer hairs which are about 20cm (8 inches) long. This coat thickens in the winter to protect it from the cold and the whitish colour acts as camouflage in the high-elevation, often snow-covered terrain it inhabits. The mountain goat lives in regions that are wintry for up to nine months of the year. Its chin is bearded and both sexes have a large but narrow head topped with slender, black horns that curve slightly backward. These horns can grow anywhere from 15 to 30cm (6 to 12 inches) in length and are very sharp (mountain goats are known to inflict serious damage upon one another in rare, but vicious fights). -

A New Mountain Goat from the Quaternary of Smith Creek Cave, Nevada

A New Mountain Goat from the Quaternary of Smith Creek Cave, Nevada By C HESTER STOCK Reprinted from the Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences, Vol. XXXV, Part S September-December, 1936 A NEW MOUNTAIN GOAT FROM THE QUATERNARY OF SMITH CREEK CAVE, NEVADA By CHESTER STOCK M. R. Harrington1 has called attention to the occurrence of a large limestone cave in the canyon wall of Smith Creek, ap proximately 34 miles north of Baker, White Pine County, Nevada. Preliminary excavations by the Southwest Museum brought to light considerable material representing a Quaternary assemblage of mammals and birds2 preserved in the cave deposits. The rela tionship of the fauna to a possible occupancy of the cavern by Man and the intrinsic interest which this assemblage possesses as coming from a site with elevation of approximately 6,200 feet, adjacent to the Bonneville basin of Utah, made a further investi gation desirable. This was undertaken with the support of the Carnegie Institution of Washington during the past summer. One of the mammals whose remains are found in the Smith Creek Cave deposits is a mountain goat. While the genus Oreamnos occurs in the Pleistocene of North America, no species distinct from that of the living type has been recorded. In the present instance, however, the animal is clearly separable spe cifically from Oreamnos americanus. Family BovrnAE 0REAMNOS HARRINGTON! n. sp. Type specimen: Parts of frontals and two horn-cores, No . • 2028, Calif. Inst. Tech. Coll. Vert. Pale., plate 35, figure 2. Paratypes: Front cannon bone, No. 2030, and hind cannon bone, No. -

WAAVP2019-Abstract-Book.Pdf

27th Conference of the World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology JULY 7 – 11, 2019 | MADISON, WI, USA Dedicated to the legacy of Professor Arlie C. Todd Sifting and Winnowing the Evidence in Veterinary Parasitology @WAAVP2019 @WAAVP_2019 Abstract Book Joint meeting with the 64th American Association of Veterinary Parasitologists Annual Meeting & the 63rd Annual Livestock Insect Workers Conference WAAVP2019 27th Conference of the World Association for the Advancements of Veterinary Parasitology 64th American Association of Veterinary Parasitologists Annual Meeting 1 63rd Annualwww.WAAVP2019.com Livestock Insect Workers Conference #WAAVP2019 Table of Contents Keynote Presentation 84-89 OA22 Molecular Tools II 89-92 OA23 Leishmania 4 Keynote Presentation Demystifying 92-97 OA24 Nematode Molecular Tools, One Health: Sifting and Winnowing Resistance II the Role of Veterinary Parasitology 97-101 OA25 IAFWP Symposium 101-104 OA26 Canine Helminths II 104-108 OA27 Epidemiology Plenary Lectures 108-111 OA28 Alternative Treatments for Parasites in Ruminants I 6-7 PL1.0 Evolving Approaches to Drug 111-113 OA29 Unusual Protozoa Discovery 114-116 OA30 IAFWP Symposium 8-9 PL2.0 Genes and Genomics in 116-118 OA31 Anthelmintic Resistance in Parasite Control Ruminants 10-11 PL3.0 Leishmaniasis, Leishvet and 119-122 OA32 Avian Parasites One Health 122-125 OA33 Equine Cyathostomes I 12-13 PL4.0 Veterinary Entomology: 125-128 OA34 Flies and Fly Control in Outbreak and Advancements Ruminants 128-131 OA35 Ruminant Trematodes I Oral Sessions -

Bovine Lungworm

Clinical Forum: Bovine lungworm Jacqui Matthews BVMS PhD MRCVS MOREDUN PROFESSOR OF VETERINARY IMMUNOBIOLOGY, DEPARTMENT OF VETERINARY CLINICAL STUDIES, ROYAL (DICK) SCHOOL OF VETERINARY STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH, MIDLOTHIAN EH25 9RG AND DIVISION OF PARASITOLOGY, MOREDUN RESEARCH INSTITUTE, MIDLOTHIAN, EH26 0PZ, SCOTLAND Jacqui Matthews Panel members: Richard Laven PhD BVetMed MRCVS Andrew White BVMS CertBR DBR MRCVS Keith Cutler BSc BVSc MRCVS James Breen BVSc PhD CertCHP MRCVS SUMMARY eggs are coughed up and swallowed with mucus and Parasitic bronchitis, caused by the nematode the L1s hatch out during their passage through the Dictyocaulus viviparus, is a serious disease of cattle. For gastrointestinal tract. The L1 are excreted in faeces over 40 years, a radiation-attenuated larval vaccine where development to the infective L3 occurs. L3 (Bovilis® Huskvac, Intervet UK Ltd) has been used subsequently leave the faecal pat via water or on the successfully to control this parasite in the UK. Once sporangia of the fungus Pilobolus. Infective L3 can vaccinated, animals require further boosting via field develop within seven days of excretion of L1 in challenge to remain immune however there have faeces, so that, under the appropriate environmental been virtually no reports of vaccine breakdown. conditions, pathogenic levels of larval challenge can Despite this, sales of the vaccine decreased steadily in build up relatively quickly. the 1980s and 90s; this was probably due to farmers’ increased reliance on long-acting anthelmintics to control nematode infections in cattle.This method of lungworm control can be unreliable in stimulating protective immunity, as it may not allow sufficient exposure to the nematode. -

Genome Assembly and Analysis of the North American Mountain Goat (Oreamnos Americanus) Reveals Species-Level Responses to Extreme Environments

GENOME REPORT Genome Assembly and Analysis of the North American Mountain Goat (Oreamnos americanus) Reveals Species-Level Responses to Extreme Environments Daria Martchenko,*,1 Rayan Chikhi,† and Aaron B. A. Shafer*,‡ *Environmental and Life Sciences Graduate Program, Trent University, K9J 7B8 Peterborough, Canada, †Institut Pasteur and CNRS, C3BI USR 3756, Paris, France, and ‡Forensics Program, Trent University, K9J 7B8 Peterborough, Canada ORCID IDs: 0000-0003-4002-8123 (D.M.); 0000-0003-1099-8735 (R.C.); 0000-0001-7652-225X (A.B.A.S.) ABSTRACT The North American mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus) is an iconic alpine species that KEYWORDS faces stressors from climate change, industrial development, and recreational activities. This species’ phy- de novo genome logenetic position within the Caprinae lineage has not been resolved and their phylogeographic history is assembly dynamic and controversial. Genomic data could be used to address these questions and provide valuable HiRise insights to conservation and management initiatives. We sequenced short-read genomic libraries con- scaffolding structed from a DNA sample of a 2.5-year-old female mountain goat at 80X coverage. We improved the demography short-read assembly by generating Chicago library data and scaffolding using the HiRise approach. The final PSMC assembly was 2,506 Mbp in length with an N50 of 66.6 Mbp, which is within the length range and in the mountain goat upper quartile for N50 published ungulate genome assemblies. Comparative analysis identified 84 gene Caprinae families unique to the mountain goat. The species demographic history in terms of effective population size generally mirrored climatic trends over the past one hundred thousand years and showed a sharp decline during the last glacial maximum. -

Allozyme Divergence and Phylogenetic Relationships Among Capra, Ovis and Rupicapra (Artyodactyla, Bovidae)

Heredity'S? (1991) 281—296 Received 28 November 7990 Genetical Society of Great Britain Allozyme divergence and phylogenetic relationships among Capra, Ovis and Rupicapra (Artyodactyla, Bovidae) E. RANOI,* G. FUSCO,* A. LORENZINI,* S. TOSO & G. TOSIt *g7ftj Nez/c nate di 9/clog/a del/a Selvaggine, Via Ca Fornacetta, 9 Ozzano dell'EmiIia (Bo) Italy, and j-Dipartimento di B/Wag/a, Universitâ diM/lana, Via Ce/ar/a, 3 Mi/epa,Italy Geneticdivergence and phylogenetic relationships between the chamois (Rupicaprini, Rupkapra rupicapra rupicapra) and three species of the Caprini (Capra aegagrus hircus, Capra ibex ibex and Ovis amrnon musUnon) have been studied by multilocus protein electrophoresis. Dendrograms have been constructed both with distance and parsimony methods. Goat, sheep and chamois pair- wise genetic distances had very similar values, All the topologies showed that Capra, Ovis and Rupicapra originate from the same internode, suggesting the hypothesis of a common, and almost contemporaneous, ancestor. The estimated divergence times among the three genera ranged from 5.28 to 7.08 Myr. These findings suggest the need to reconsider the evolutionary relationships in the Caprinae. Keywords:allozymes,Caprinae, electrophoresis phylogenetic trees. caprid lineage since the lower or middle Miocene. Introduction ShaDer (1977) agrees with the outline given by Thenius Theevolutionary relationships of the subfamily & Hofer (1960) supporting the idea of a more recent Caprinae (Artyodactyla, Bovidae; Corbet, 1978) have origin of the Caprini, and in particular of a Pliocenic been discussed by Geist (197!) within the framework splitting of Ovis and Capra. In Geist's (1971) opinion of his dispersal theory of Ice Age mammal evolution. -

Mountain Goat Scientific Name: Oreamnos Americanus Species Code: M-ORAM Status: Yellow Listed Distribution • Provincial Range

Mountain Goat Scientific Name: Oreamnos americanus Species Code: M-ORAM Status: Yellow listed Distribution • Provincial Range The present distribution of mountain goats in the province has changed little from that of historical times. However, some populations have been exterminated and in many parts of its range numbers have decreased due to habitat loss, disease or starvation and over-hunting. Mountain goats are found throughout suitable habitats in a variety of biogeoclimatic zones on the mainland of British Columbia. In British Columbia mountain goats are most abundant in the Rocky Mountains, scattered populations exist in the coastal mountain and in northern mountains and plateaus (Stevens and Lofts 1988). • Elevational Range: Usually >1500 m • Provincial Context Mountain goats are restricted to the northwest portion of North America, including British Columbia. British Columbia has more native goat range than any other province. The 1997 provincial population estimate for mountain goats was 50,000 (Hatter 1997). • Range in Project Area: Ecoprovince: Southern Interior Mountains Ecoregions: Columbia Mountains and Highlands, Southern Rocky Mountain Trench, Western Continental Ranges Ecosections: Eastern Purcell Mountains, East Kootenay Trench, Southern Park Ranges Biogeoclimatic Zones: IDFdm2, MSdk, ESSFdk; ESSFdku; ESSFdkp; ESSFwm; ESSFwmu; ESSFwmp; AT Ecology and Key Habitat Requirements The mountain goat is a generalist herbivore. Habitat selection is determined more by topographical features rather than by the presence of specific forage species. Mountain goats inhabit rugged terrain comprised of cliffs, ledges, projecting pinnacles and talus slopes in subalpine and alpine habitats. Forage sites for mountain goats must be adjacent to suitable landforms to which they can retreat in times of danger. -

Oreamnos Americanus): Support for Meeting Metabolic Demands B.L

599 ARTICLE Geophagic behavior in the mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus): support for meeting metabolic demands B.L. Slabach, T.B. Corey, J.R. Aprille, P.T. Starks, and B. Dane Abstract: Geophagy, the intentional consumption of earth or earth matter, occurs across taxa. Nutrient and mineral supple- mentation is most commonly cited to explain its adaptive benefits; yet many specific hypotheses exist. Previous research on mountain goats (Oreamnos americanus (Blainville, 1816)) broadly supports nutrient supplementation as the adaptive benefit of geophagy. Here, we use data from an undisturbed population of mountain goats inhabiting a geologically distinct coastal mountain range in southwestern British Columbia to test the hypothesis that geophagic behavior is a proximate mechanism for nutrient supplementation to meet metabolic demands. Our population, observed for over 30 consecutive years, returned each year with high fidelity to the same geophagic lick sites. Logistic regression demonstrated an overall effect of sodium and phosphorus, but not magnesium and calcium, on lick preferences. These data, in conjunction with field observations, provide support for the hypothesis that geophagy provides nutrient supplementation and that geophagy may be an obligate behavior to meet necessary metabolic demands within this population. The implications of our results suggest the necessity to preserve historically important habitats that may be necessary for population health. Key words: geophagy, mountain goat, Oreamnos americanus, mineral supplementation. Résumé : La géophagie, la consommation intentionnelle de terre ou de substances de la terre, est observée chez de nombreux taxons. L’explication de ses avantages adaptatifs fait le plus souvent appel a` la supplémentation de nutriments et de minéraux, bien qu’il existe de nombreuses hypothèses distinctes. -

Insular Vertebrate Evolution: the Palaeontological Approach"

14 MITOCHONDRIAL AND NUCLEAR GENES FROM THE EXTINCT BALEARIC BOVID MYOTRAGUS BALEARlCUS Carles LALUEZA-Fox, Lourdes SAMPJETRO, Tomàs MARQuÈs, Josep Antoni ALcovER & Jaume BERTRANPETIT LALUEZA-Fox, C, SAM PIETRO, L., MARQuÈs, T., ALCOVER, J. A. & BERTRANPETIl; J. 2005. Mitochondrial and nuclear genes [TOm the extinct Balearic bovid Myotragus balearicus. In ALCOVER, JA & BOVER, P. (eds.): Proceedings of the International Symposium "Insular Vertebrate Evolution: the Palaeontological Approach". Monografies de la Societat d'Història Natural de les Balears, 12: 145-154. Resum Myotragus balearicus és un bòvid extingit de les lIJes Balears Orientals o Gimnèsies (Mallorca, Menorca i illots que les envolten). Myotragus presenta nombroses novetats evolutives que enfosqueixen el seu emplaçament taxonòmic dintre dels Caprinae. A un projecte desenvolupat els darrers anys hem analitzat diferents mostres d'ossos de Myotragus i hem recupe rat el gen cytb mtDNA complet, una seqüència del gen 12S mtDNA, una seqüència de la regió D-Ioop, i una seqüència d'un gen nuclear multi-còpia (el rDNA 28 S), emprant tècniques de DNA antic. Diferents controls experimentals, incloent-hi un laboratori dedicat, obtenció independent de rèpliques, solapament de fragments, extraccions múltiples i clonatge de pro ductes PCR, donen suport a l'autenticitat de les seqüències. Els arbres filogenètics nous situen consistentment Myotragus a una posició basal al clade Ouis-Budorcas. Emperò, alguns gèneres de Caprinae, tals com Otearnnos i Amnotragus, presenten posicions inestables a tots els arbres. La branca llarga observada a Myotragus correspon a una taxa evolutiva elevada a aques ta línia que podria estar associada a la seva petita mida corporal. A més, la recuperació de gens nuclears per primera vegada d'una espècie extingida de la Mediterrània obre noves possibilitats de recerca sobre els trets genòmics i fenotípics. -

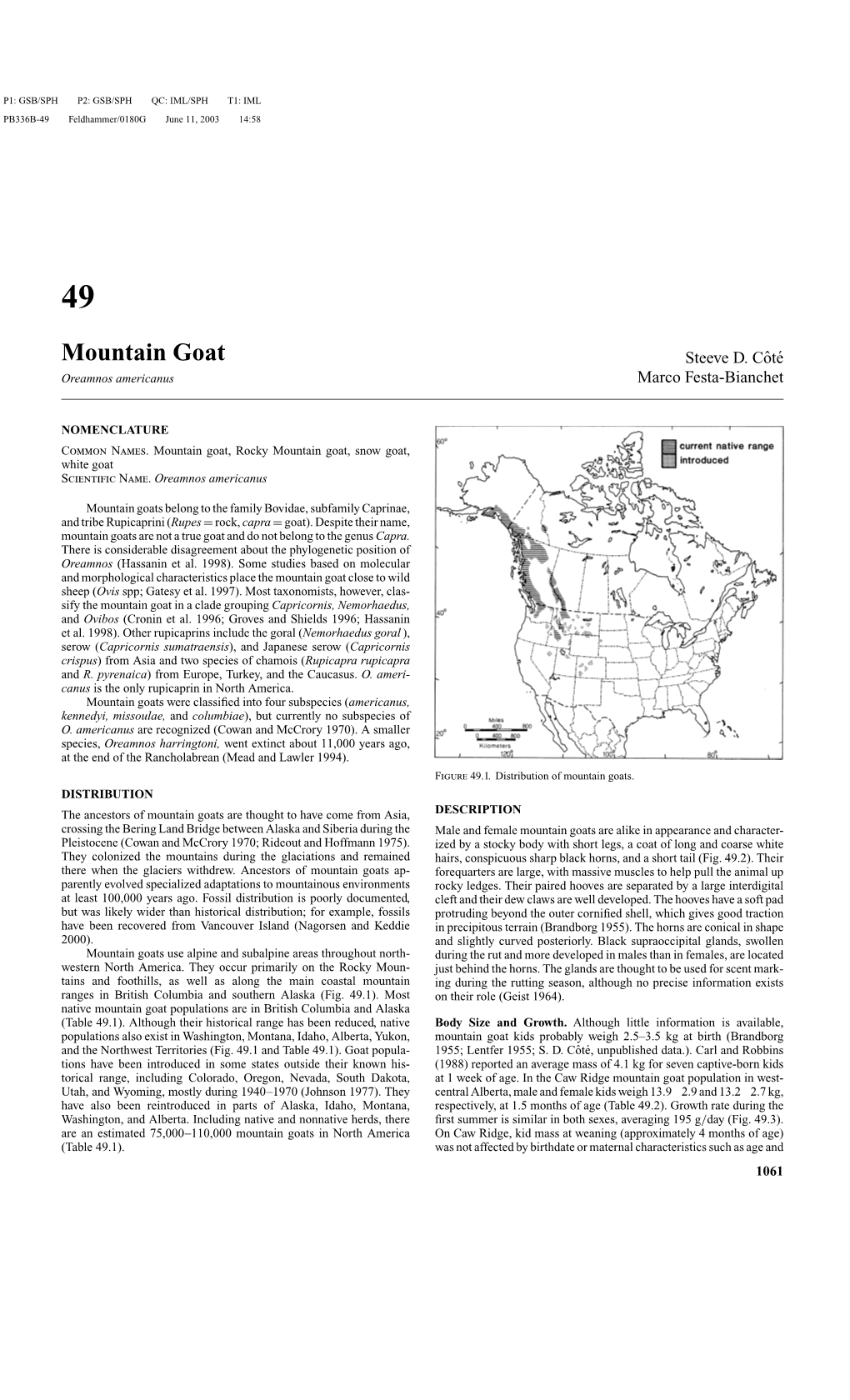

Mountain Goat, Oreamnos Americanus

CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT: The overhunting of bison to the brink of extinction, fol- lowed by the protection and fostering of the last remaining wild bison in and around Yellow- stone National Park is one of the iconic stories of wildlife conservation in the United States.13 In 1902, the last 20 or so free-ranging bison in Yellowstone National Park were augmented by 21 bison brought from private herds elsewhere. The captive herd grew to >1000 animals, and the free-ranging herd increased slowly as well. As of 2012, Yellowstone National Park managed to achieve a population size of 2500–4500. The Jackson Hole population was esti- mated at 927 in 2012, and the population objective was 500.14 Brucellosis, an Old World bac- terial disease of bison, cattle and elk, was discovered in Yellowstone in 1917, and all bison in the state have subsequently been managed so as to reduce possible contact with domestic cattle. Of 199 animals from the Jackson Hole herd tested for brucellosis during 2000–2008, 40–83% were positive, depending on year.15 NOTES AND REFERENCES 1. Meagher (1986). 2. Commission Regulation 41. 3. Wilson and Reeder (2005). 4. Wilson (1996). 5. Halbert and Derr (2007). 6. Hedrick (2009). 7. Fryxell (1926, 1928), Cannon (2007), author for Hunt Mountain. 8. Russell (1921). 9. Hornaday (1887). 10. Bruggeman et al. (2007). 11. Fuller et al. (2007). 12. Laundré et al. (2001). 13. Plumb and Sucec (2006). 14. Wyoming Game and Fish Department (2011). 15. Baskin (1998), Scurlock and Edwards (2010). Mountain goat, Oreamnos americanus DESCRIPTION: A medium-sized even-toed ungulate with all-white pelage; pelage is short and pure white in late summer, and shaggy and soiled by late spring.