Is Being a Decent President Enough for a Prestigious Prize?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mo Ibrahim Foundation Announces No Winner of 2019 Ibrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership

Mo Ibrahim Foundation announces no winner of 2019 Ibrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership LONDON, 5 March 2020 – Today, the Mo Ibrahim Foundation announces that there is no winner of the 2019 Ibrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership. This decision has been made following deliberations by the independent Prize Committee. Announcing the decision, Prize Committee Chair Festus Mogae commented: “The Ibrahim Prize recognises truly exceptional leadership in Africa, celebrating role models for the continent. It is awarded to individuals who have, through the outstanding governance of their country, brought peace, stability and prosperity to their people. Based on these rigorous criteria, the Prize Committee could not award the Prize in 2019.” Commenting on the decision, Mo Ibrahim, Chairman of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation said: “Africa is facing some of the toughest challenges in the world – ranging from those connected to population growth, and economic development, to environmental impact. We need leaders who can govern democratically and translate these challenges into opportunities. With two-thirds of our citizens now living in better-governed countries than ten years ago, we are making progress. I am optimistic that we will have the opportunity to award this Prize to a worthy candidate soon.” Contacts For more information, please contact: Zainab Umar, [email protected], +44 (0) 20 7535 5068 MIF media team, [email protected], +44 (0) 20 7554 1743 Join the discussion online using the hashtag -

National Namibia Concerns ~ ~ 915 East 9Th Avenue· Denver, Colorado 80218 • (303) 830-2774

National Namibia Concerns ~ ~ 915 East 9th Avenue· Denver, Colorado 80218 • (303) 830-2774 November 15, 1989 Dear friends, One Namibia! One nationl That has been the rallying cry for years as we worked to bring an end to South Africa's illegal occupation of Namibia. Last week, the Namibian people took a long step toward that goal, with their whole-hearted participation in elections that have been certified as "free and fair" by the United Nations. Enclosed are reports which show the final voting results as well as the names of the delegates from each party who will meet to draft the constitution for a free Namibia. There was surprise in some quarters about the size of the vote that went for the DTA--the South African supported political party. Indeed there were some anxious hours as the DTA actually led in the vote count until the ballots from Ovamboland came in. We feel that SWAPO's 57% was very good considering that the voter registration laws, drawn up by South Africa, permitted non-residents to vote, and that .thousands of South Africans and Angolans entered Namibia to vote for the DTA. Generally, there seems to be a feeling of rejoicing--as reflected in the statement by Bishop Kleopas Dumeni ...Joy that the elections have been held and thankfulness that there was so little violence during the week of voting. In a country that has known so much violence for so many years, the relative peacefulness of the past ten days is something that we hardly expected, and for which we are deeply grateful! We plan to publish a Namibia Newsletter within the next two weeks and hope to have more stories and pictures of the election week. -

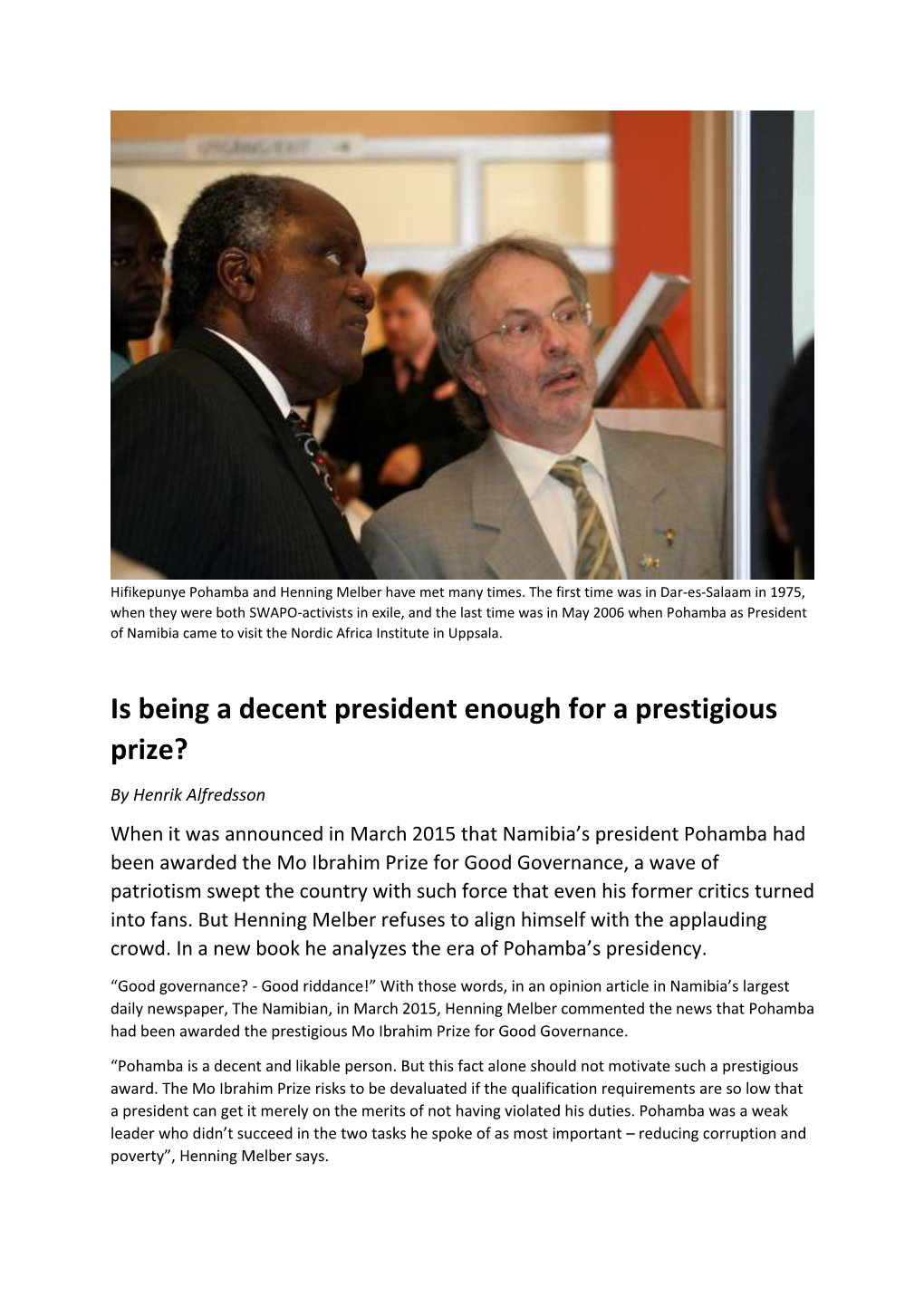

Namibia:Unfinished Business Within the Ruling Part

Focus on Namibia Namibia: Unfinished business within the ruling party There is a new president at the helm, but the jostling for position within the ruling Swapo party, which started in 2004, has not ended. Would the adversaries’ long-held dream that the strongest and most viable opposition in Namibia emerges from within the ranks of Swapo itself, come true? Axaro Gurirab reports from Windhoek. “Can you believe it: the sun is still significant and gallant contribution to the These questions are relevant because rising in the East and setting in the West!” So democratisation of Africa. during the week leading up to the May 2004 exclaimed a colleague of mine on the occasion The political transition had seen a heated extraordinary congress, Nujoma fired of the inauguration of President Hifikepunye contest between three Swapo heavyweights, Hamutenya as foreign minister, as well as the Pohamba on 21 March 2005. This simple namely Swapo vice-president Hifikepunye then deputy foreign minister, Kaire Mbuende. observation was quite profound because until Pohamba, current prime minister Nahas Angula, It was thought at the time that Nujoma, who then many people had been at their wits’ end and former foreign affairs minister Hidipo was personally campaigning for Pohamba, took trying to imagine Namibia without Sam Nujoma, Hamutenya. these drastic steps in order to send a strong the president of the ruling Swapo party. At the extraordinary party congress in May message to the congress delegates about who He had been the country’s first president, 2004, Angula fell out in the first round, and he liked and did not like. -

Biography-Sam-Nujoma-332D79.Pdf

BIOGRAPHY Name: Sam Nujoma Date of Birth: 12 May 1929 Place of Birth: Etunda-village, Ongandjera district, North- Western Namibia – (Present Omusati Region) Parents: Father: Daniel Uutoni Nujoma - (subsistence farmer) Mother: Helvi Mpingana Kondombolo- (subsistence farmer) Children: 6 boys and 4 girls. From Childhood: Like all boys of those days, looked after his parents’ cattle, as well as assisting them at home in general work, including in the cultivation of land. Qualifications: Attended Primary School at Okahao Finnish Mission School 1937-1945; In the year 1946, Dr. Nujoma moved to the coastal town of Walvisbay to live with his aunt Gebhart Nandjule, where in 1947 at the age of 17 he began his first employment at a general store for a monthly salary of 10 Shillings. It was in Walvis Bay that he got exposed to modern world politics by meeting soldiers from Argentina, Norway and other parts of Europe who had been brought there during World War II. Soon after, at the beginning of 1949 Dr. Nujoma went to live in Windhoek with his uncle Hiskia Kondombolo. In Windhoek he started working for the South African Railways and attended adult night school at St. Barnabas in the Windhoek Old Location. He further studied for his Junior Certificate through correspondence at the Trans-Africa Correspondence College in South Africa. Marital Status: On 6 May 1956, Dr Nujoma got married to Kovambo Theopoldine Katjimune. They were blessed with 4 children: Utoni Daniel (1952), John Ndeshipanda (1955), Sakaria Nefungo (1957) and Nelago (1959), who sadly passed away at the age of 18 months, while Dr. -

Namibia Relations Political Relations India and Namibia Enjoy Warm And

India - Namibia Relations Political Relations India and Namibia enjoy warm and cordial relations. India was at the forefront of the liberation struggle of Namibia and was indeed among the first nations to raise the question of Namibian independence in the UN. The first SWAPO Embassy abroad was established in New Delhi in 1986 which was closed after independence of Namibia in 1990. Diplomatic relations with independent Namibia were established right from the moment of its independence, with the Observer Mission being upgraded to a full-fledged High Commission on 21 March 1990. Namibia opened a full-fledged resident Mission in New Delhi in March 1994. Bilateral, political interactions between our two countries have been at the highest levels. Prime Minister V.P. Singh visited Namibia in March 1990 for Namibia’s Independence Celebrations, accompanied by Shri K.R. Narayanan, Shri Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and the then Leader of the Opposition, Shri Rajiv Gandhi; Dr. Shanker Dayal Sharma, Hon’ble President of India in June 1995; Prime Minister Vajpayee in 1998; and numerous ministerial delegations. Col.Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore (Retd.), AVSM, MoS for I&B visited as Special Envoy of the Prime Minister on 28 August 2015 to hand over IAFS-III invitations to Namibian dignitaries. From Namibia, Dr. Sam Nujoma, Founding President of Namibia visited India 13 times in the past since 1983 and the recent one being from 17-22 November 2015 under the Distinguished Visitors’ Programme of ICCR; Prime Minister Dr. Hage Geingob in 1995; President Hifikepunye Pohamba in 2009; and several ministerial delegations. The visit of President Pohamba to India in 2009 was a milestone, leading to an acceleration of relations across the spectrum. -

Tells It All 1 CELEBRATING 25 YEARS of DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS

1989 - 2014 1989 - 2014 tells it all 1 CELEBRATING 25 YEARS OF DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS Just over 25 years ago, Namibians went to the polls Elections are an essential element of democracy, but for the country’s first democratic elections which do not guarantee democracy. In this commemorative were held from 7 to 11 November 1989 in terms of publication, Celebrating 25 years of Democratic United Nations Security Council Resolution 435. Elections, the focus is not only on the elections held in The Constituent Assembly held its first session Namibia since 1989, but we also take an in-depth look a week after the United Nations Special at other democratic processes. Insightful analyses of Representative to Namibia, Martii Athisaari, essential elements of democracy are provided by analysts declared the elections free and fair. The who are regarded as experts on Namibian politics. 72-member Constituent Assembly faced a We would like to express our sincere appreciation to the FOREWORD seemingly impossible task – to draft a constitution European Union (EU), Hanns Seidel Foundation, Konrad for a young democracy within a very short time. However, Adenaur Stiftung (KAS), MTC, Pupkewitz Foundation within just 80 days the constitution was unanimously and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) adopted by the Constituent Assembly and has been for their financial support which has made this hailed internationally as a model constitution. publication possible. Independence followed on 21 March 1990 and a quarter We would also like to thank the contributing writers for of a century later, on 28 November 2014, Namibians their contributions to this publication. We appreciate the went to the polls for the 5th time since independence to time and effort they have taken! exercise their democratic right – to elect the leaders of their choice. -

Ipumbu Shiimi: Namibia's New Generation of Banknotes

Ipumbu Shiimi: Namibia’s new generation of banknotes Remarks by Mr Ipumbu Shiimi, Governor of the Bank of Namibia, at the official launch of the new banknotes during the 22nd Independence Anniversary celebrations, Mariental, Hardap Region, 21 March 2012. * * * Directors of Ceremony Your Excellency Dr Hifikepunye Pohamba, President of the Republic of Namibia and First Lady Meme Pohamba Right Honourable Prime Minister, Nahas Angula Honourable Speaker of the National Assembly, Dr. Theo Ben Gurirab Honourable Chairperson of the National Council, Asser Kapere Honourable Chief Justice, Judge Peter Shivute Honourable Ministers Honourable Members of Parliament Members of the Diplomatic Corps Honourable Katrina Hanse-Himarwa, Governor of the Hardap Region and other Governors from other regions Your Worship, Alex Kamburute, Mayor of Mariental and other Mayors from other local authorities Local and Regional Authority Councillors, Traditional Leaders Senior Government Officials Members of the Media Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen Good afternoon I am humbled and privileged for this opportunity to make few remarks and introduce the video about Namibia’s new generation of banknotes. Today is a special and momentous Day in the history of our beloved country. Today, we are not only celebrating 22 years of our Independence, we are not only celebrating 22 years of peace and stability, but we also witnessed the launch of the new generation of Namibia’s banknotes by his Excellency, the President of the Republic. Your Excellency, Directors of Ceremonies! The theme of my remarks is titled “Our Money, Our Pride, Our heroes and heroines, we Honour, know your currency”. This is because the new banknotes launched a moment ago are not just decorated papers but are very important national payment instruments that symbolize our sovereignty, nationhood, and natural diversity. -

Republic of Namibia Inaugural Address by His Excellency Dr Hage G. Geingob President of the Republic of Namibia at the 25Th In

REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA INAUGURAL ADDRESS BY HIS EXCELLENCY DR HAGE G. GEINGOB PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA AT THE 25TH INDEPENDENCE DAY CELEBRATION AND SWEARING IN OF THE 3RD PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA MARCH 21, 2015 INDEPENDENCE STADIUM WINDHOEK Director of Ceremonies; Your Excellency, and my predecessor, Comrade Hifikepunye Lucas Pohamba; Your Excellency, Founding Father, Comrade Sam Shafiishuna Nujoma; Your Excellency, President Robert Gabriel Mugabe, President of Zimbabwe and Chairman of both the AU and SADC; Madam Nkosozana Dlamini-Zuma, Chairperson of the AU Commission Your Majesty King of Swaziland, Mswati the Third and Her Royal Highness; Your Excellencies, Heads of State and Government; Former Heads of State and Government; Honourable Speaker of the National Assembly; Honourable Chairperson of the National Council; Honourable Chief Justice of the Republic of Namibia; Honourable Members of Parliament; Leaders of Political Parties; Members of the Diplomatic Corps; Traditional and Spiritual leaders, Distinguished Invited Guest; Members of the local and international press corps Fellow Namibians. 1 It gives me great pleasure to see so many of you from so many different nations as well as our citizens from all corners of the Land of the Brave. I bid you all a hearty welcome. “This is the day the Lord has made. We will rejoice and be glad in it.” This day would not have come about without the committed leadership legacy left by those before me. Permit me to start with my mentor, Founding Father of the Nation, Comrade Sam Shafiishuuna Nujoma. He is an icon of Namibia’s struggle for Independence and a man who brought peace to a nation that was tired of war. -

From Nujoma to Geingob: 25 Years of Presidential Democracy Henning Melber*

Journal of Namibian Studies, 18 (2015): 49 – 65 ISSN 2197-5523 (online) From Nujoma to Geingob: 25 years of presidential democracy Henning Melber* Abstract Namibia’s first 25 years of independence were characterized politically by a demo- cratic regime influenced by the presidential governance of Sam Nujoma (1990– 2005) and Hifikepunye Pohamba (2005–2015). With Hage Geingob, sworn in on Independence Day 2015, the third (and probably last) of the first ‘struggle generation’ entered the highest state office on behalf of Swapo, the former liberation movement now in firm political control. This article takes stock of Namibia’s presidential democracy by summarizing the institutional and structural features contributing to the strong executive role of Namibian presidents. It assesses the terms in office of the first two Heads of State and provides insights into Geingob’s path to office and his efforts to consolidate his status. It characterizes and compares the different personalities of the Namibian presidents and their style of political rule. It ends with a preliminary outlook at what might be expected from the current president Hage Geingob. Introduction Presidential politics have emerged as a new focus for scholarly debate, seeking to explore further the impact and influence of presidents in democratic settings within a multi-party environment.1 Such debate on what is also termed ‘presidentialization’ might find a fertile ground in a Namibian case study. At the centre of interest is the impact and negotiating space presidents have or seek vis-à-vis the political party or parties and the manoeuvring space utilized and applied.2 * Henning Melber has been the Director of the Namibian Economic Policy Research Unit (NEPRU) in Windhoek (1992–2000), Research Director of the Nordic Africa Institute (2000–2006) and Executive Director of the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation (2006–2012), both in Uppsala. -

Nationalist Masculinity in Sam Nujoma's Autobiography

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 19th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 24th, 9:00 AM - 9:50 AM Fighting the Lion: Nationalist Masculinity in Sam Nujoma's Autobiography Kelly J. Fulkerson Dikuua The Ohio State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Fulkerson Dikuua, Kelly J., "Fighting the Lion: Nationalist Masculinity in Sam Nujoma's Autobiography" (2017). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 2. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2017/001/2 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Fighting the Lion: Nationalist Masculinity in Sam Nujoma’s Autobiography Abstract Dr. Samuel Nujoma’s autobiography, Where Others Wavered: My Life in SWAPO and My Participation in the Liberation Struggle, documents his life as a pivotal figure in the Namibian war for independence leading to his tenure as the first president of Namibia (1990-2005). Nujoma, known as the “Founding Father” of Namibia, occupies a larger-than-life sphere within the public imagination through monuments, public photographs, placards and street names. Nujoma’s autobiography prescribes a certain type of national citizenship that details a specific construction of masculinity for Namibian men. This paper analyzes his autobiography, arguing that Nujoma constructs a hegemonic masculinity based on four key features: 1. leadership; 2. initiation to manhood; 3. the use of physical strength; 4. -

Tribute by H. E. Dr. Sam Nujoma, Founding President

TRIBUTE BY H. E. DR. SAM NUJOMA, FOUNDING PRESIDENT AND FATHER OF THE NAMIBIAN NATION, ON THE OCCASION OF THE STATE FUNERAL IN HONOUR OF THE LATE HONOURABLE DR THEO-BEN GURIRAB 20 JULY 2018 PARLIAMENT GARDEN WINDHOEK, KHOMAS REGION Check Against Delivery 0 | Page Directors of Proceedings; Madam Joan Guriras, the Children and the Entire Bereaved Family of the Late Comrade Dr. Theo-Ben Gurirab; Your Excellency Dr. Hage Geingob, President of the Republic of Namibia and Madam Monica Geingos, First Lady; Your Excellency Dr. Hifikepunye Pohamba, Former President of the Republic of Namibia and Madam Penexupifo Pohamba, Former First Lady; Your Excellency Comrade Nangolo Mbumba, Vice President of the Republic of Namibia and Madam Mbumba; Your Excellency, Dr Nickey Iyambo, Former Vice President of the Republic of Namibia and Madam Iyambo; Right Honourable, Dr Saara Kuugongelwa –Amadhila, Prime Minister of the Republic of Namibia and Comrade Amadhila; Honourable Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of International Relations and Cooperation and Retired Lieutenant General Ndaitwah; Honourable Professor Peter Katjavivi, Speaker of the National Assembly and Madam Katjavivi; Honourable Margaret Mensah-Williams, Chairperson of the National Council and Mr Williams; Honourable Peter Shivute, Chief Justice and Judge Shivute; Honourable Ministers and Deputy Ministers; Honourable Members of Parliament; Comrade Sofia Shaningwa, Secretary General of SWAPO Party; Honourable McHenry Venaani, Leader of the Official Opposition; Honourable -

NAMIBIA Namibia Is a Multiparty Democracy with a Population Of

NAMIBIA Namibia is a multiparty democracy with a population of approximately 2.2 million. The presidential and parliamentary elections held in November 2009 resulted in the reelection of President Hifikepunye Pohamba and the retention by the ruling South West Africa People's Organization (SWAPO) of its parliamentary majority. Despite some irregularities, international observers characterized the election as generally free and fair. In March the High Court dismissed a challenge to the election outcome filed by nine opposition parties; however, in September the Supreme Court overturned the decision and sent the case back to the High Court, where the case remained pending at year's end. Security forces reported to civilian authorities. Human rights problems included police use of excessive force; prison overcrowding and poor conditions in detention centers; arbitrary arrest, prolonged pretrial detention, and long delays in trials; criticism of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs); harassment and political intimidation of opposition members; and official corruption. Societal abuses included violence against women and children, including rape and child abuse; discrimination against women, ethnic minorities, and indigenous people; child trafficking; discrimination and violence based on sexual orientation and gender identity; and child labor. RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life There were no reports that the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. There were no developments in the 2008 case in which a police officer shot and killed a demonstrator who stabbed a police constable during a political rally. On April 22, seven of the nine police officers accused of killing a suspect during interrogation in 2006 were found guilty of culpable homicide, assault with intent to do grievous bodily harm, and obstructing the course of justice.