A Never-Ending Sojourn by Diana Paiz Engle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Journey to Mars: How Donna Shirley Broke Barriers for Women in Space Engineering

The Journey to Mars: How Donna Shirley Broke Barriers for Women in Space Engineering Laurel Mossman, Kate Schein, and Amelia Peoples Senior Division Group Documentary Word Count: 499 Our group chose the topic, Donna Shirley and her Mars rover, because of our connections and our interest level in not only science but strong, determined women. One of our group member’s mothers worked for a man under Ms. Shirley when she was developing the Mars rover. This provided us with a connection to Ms. Shirley, which then gave us the amazing opportunity to interview her. In addition, our group is interested in the philosophy of equality and we have continuously created documentaries that revolve around this idea. Every member of our group is a female, so we understand the struggles and discrimination that women face in an everyday setting and wanted to share the story of a female that faced these struggles but overcame them. Thus after conducting a great amount of research, we fell in love with Donna Shirley’s story. Lastly, it was an added benefit that Ms. Shirley is from Oklahoma, making her story important to our state. All of these components made this topic extremely appealing to us. We conducted our research using online articles, Donna Shirley’s autobiography, “Managing Martians”, news coverage from the launch day, and our interview with Donna Shirley. We started our research process by reading Shirley’s autobiography. This gave us insight into her college life, her time working at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and what it was like being in charge of such a barrier-breaking mission. -

Long-Range Rovers for Mars Exploration and Sample Return

2001-01-2138 Long-Range Rovers for Mars Exploration and Sample Return Joe C. Parrish NASA Headquarters ABSTRACT This paper discusses long-range rovers to be flown as part of NASA’s newly reformulated Mars Exploration Program (MEP). These rovers are currently scheduled for launch first in 2007 as part of a joint science and technology mission, and then again in 2011 as part of a planned Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission. These rovers are characterized by substantially longer range capability than their predecessors in the 1997 Mars Pathfinder and 2003 Mars Exploration Rover (MER) missions. Topics addressed in this paper include the rover mission objectives, key design features, and Figure 1: Rover Size Comparison (Mars Pathfinder, Mars Exploration technologies. Rover, ’07 Smart Lander/Mobile Laboratory) INTRODUCTION NASA is leading a multinational program to explore above, below, and on the surface of Mars. A new The first of these rovers, the Smart Lander/Mobile architecture for the Mars Exploration Program has Laboratory (SLML) is scheduled for launch in 2007. The recently been announced [1], and it incorporates a current program baseline is to use this mission as a joint number of missions through the rest of this decade and science and technology mission that will contribute into the next. Among those missions are ambitious plans directly toward sample return missions planned for the to land rovers on the surface of Mars, with several turn of the decade. These sample return missions may purposes: (1) perform scientific explorations of the involve a rover of almost identical architecture to the surface; (2) demonstrate critical technologies for 2007 rover, except for the need to cache samples and collection, caching, and return of samples to Earth; (3) support their delivery into orbit for subsequent return to evaluate the suitability of the planet for potential manned Earth. -

Autonomous Navigation and the Sojourner Microrover

rtRR.31. lYYf3 5: 4“(7-TI 5L1FLNCE RRIWROD NO. >y~ 1-’.1313 m TI-113PATNFINDERIVWSIONmhf.ms tbas@iweofMarostthetime the d F ; Iandar completed sun-finding and identifi 3 the cliraetion of mrirtiannorth on 90! 1. Int$ 4 Autonomous Navigation and the madkfe wqqmints (ss needed) were also de- tined by the driver if them was a preferent$l : Sojourner Microrover path toward the fml dcstindors (such ss a 7 . route to avoid obvious hazsrds along t$e 8 path). If the rover was not slreody faoing e 9 J. Matijevic next waypoinL it was carunandsd to 10 toward tbe god until it facd the destination+ 11 These oommnds (W30to Waypointfl tuqs, 12 and a command to update the position of e TtM Mars ex@xation program has as an ing, the rover used teobniques for aukmo- rover in the x and y coordinate tie) w e i: ovmamhingtheme tho mamh for md under- mous control which were (among sewed sent to tho rovor as part of a single c d stnnding of life, climate, and resou.moson technologies)tkst damonstrate$in flight on sequence. 4 15 16 this fascinating planet. The abfiity to move this mission. One such technique for Upon exeoution of tha “Go to Waypo”mt” 17 aboutthe surfiiof Mars is key to makb autonomow navigation and hszad avoidance cunmand the rover drove an appmxirrde 18 measuremcmtsand the gathuirtg of tha straight lina, ac@9& - its ps data which address this therm (J). In Oc- when it datacted drifi off ils co c ;: tober 1992, the NASA Office of Spaea or enoountoreda tid condili 21 Access and kbno]o~ fdod an ex- king cxooutionof a “Go to Wai - 22 periment to d~nsti~ the mobile vti- point” eomrnsnd,the rover updstdd 23 ck technologiesneeded for a Msrs surl%oc its position relntive to the lander {o 24 mission (2), lllat exporimlmh the Micro- dexarmine(at a mioirnurn) if it ~d rover Flight Expmimcnt (MJ?EX) or reaohed the objeotivc of the trsy- : “So@mer;’ flew on tbe Mars Pathfinder erse. -

Three Women Who Dared Rabbi Van Lanckton Temple B’Nai Shalom Braintree, Massachusetts March 4, 2017

Three Women Who Dared Rabbi Van Lanckton Temple B’nai Shalom Braintree, Massachusetts March 4, 2017 Be happy, it’s Adar! The new month of Adar began last Monday. Next weekend, we celebrate Purim. Spring is finally almost here. In addition to sending sh’lach manot and eating hamentaschen and dressing up in costumes, the central celebration of Purim is the public reading of the Book of Esther, Megillat Esther. Esther is the prime example of a woman who dared. She dared to speak up to King Achashverosh. She dared to enter his throne room without his permission, risking death. She accused Haman, powerful counselor to the king, of plotting to kill the Jews. In doing so, she revealed to the king that she, herself, was Jewish. If she had failed, she would have shared in the fate of all the Jews of Persia in being killed by Haman and his followers. Before these exploits, Esther was unsure what to do. Her uncle Mordecai urged her to use her position as queen to save the Jews. We need to back up a little in the story to understand the exchange between Mordecai and Esther and the key line in that exchange that still speaks to us today. Megillat Esther tells us that the king had promoted Haman and seated him higher than any of his fellow officials. All the king’s courtiers knelt and bowed low to Haman according to the king’s order, but Mordecai would not kneel or bow low. He refused to do so, he said, because he was a Jew. -

Insight Spacecraft Launch for Mission to Interior of Mars

InSight Spacecraft Launch for Mission to Interior of Mars InSight is a robotic scientific explorer to investigate the deep interior of Mars set to launch May 5, 2018. It is scheduled to land on Mars November 26, 2018. It will allow us to better understand the origin of Mars. First Launch of Project Orion Project Orion took its first unmanned mission Exploration flight Test-1 (EFT-1) on December 5, 2014. It made two orbits in four hours before splashing down in the Pacific. The flight tested many subsystems, including its heat shield, electronics and parachutes. Orion will play an important role in NASA's journey to Mars. Orion will eventually carry astronauts to an asteroid and to Mars on the Space Launch System. Mars Rover Curiosity Lands After a nine month trip, Curiosity landed on August 6, 2012. The rover carries the biggest, most advanced suite of instruments for scientific studies ever sent to the martian surface. Curiosity analyzes samples scooped from the soil and drilled from rocks to record of the planet's climate and geology. Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Begins Mission at Mars NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter launched from Cape Canaveral August 12. 2005, to find evidence that water persisted on the surface of Mars. The instruments zoom in for photography of the Martian surface, analyze minerals, look for subsurface water, trace how much dust and water are distributed in the atmosphere, and monitor daily global weather. Spirit and Opportunity Land on Mars January 2004, NASA landed two Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, on opposite sides of Mars. -

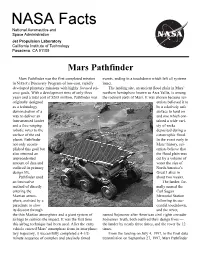

Mars Pathfinder

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91109 Mars Pathfinder Mars Pathfinder was the first completed mission events, ending in a touchdown which left all systems in NASAs Discovery Program of low-cost, rapidly intact. developed planetary missions with highly focused sci- The landing site, an ancient flood plain in Mars ence goals. With a development time of only three northern hemisphere known as Ares Vallis, is among years and a total cost of $265 million, Pathfinder was the rockiest parts of Mars. It was chosen because sci- originally designed entists believed it to as a technology be a relatively safe demonstration of a surface to land on way to deliver an and one which con- instrumented lander tained a wide vari- and a free-ranging ety of rocks robotic rover to the deposited during a surface of the red catastrophic flood. planet. Pathfinder In the event early in not only accom- Mars history, sci- plished this goal but entists believe that also returned an the flood plain was unprecedented cut by a volume of amount of data and water the size of outlived its primary North Americas design life. Great Lakes in Pathfinder used about two weeks. an innovative The lander, for- method of directly mally named the entering the Carl Sagan Martian atmos- Memorial Station phere, assisted by a following its suc- parachute to slow cessful touchdown, its descent through and the rover, the thin Martian atmosphere and a giant system of named Sojourner after American civil rights crusader airbags to cushion the impact. -

The Mars Pathfinder Project

CaseStudy The Mars PathfinderProject Introduction In 1992budgets throughout the U.S. government were being slashedas the post-Cold War drawdown gathered momentum. Support for expensive space exploration projects was waning and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) relationship with politicians and the general public had been strained by recent high-profile, expensive project failures. "The new NASA A.dministrator determined that the United States must continue to do space science missions despite the government-wide belt tightening that had squeezed the NASA budget, began talking about 'Faster, Better, Cheaper.' The catch- phrase summed up a philosophy that was right in step with the new adrninistration's practical thinking" (Muirhead & Simon, 1999). For NASA, this mantra meant increasing the number of planetary rnissions, spending less than $150 million (US) on each mission and taking no longer than 36 months for implernentation. Frojects that took longer or cost more would be canceled. With this philosophy, NASA teamed with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory 0PL) and embarked on a project to land a scientific exploration module on the planet of Mars. This proiect was known as the Mars Pathfinder (MPF) mission. More than three years later, NASA and JPL received their last scientific data transmission from the MPF. This transmission marked the culmination of a phenomenal rnission that far exceeded all rightful expectations. Both in terms of science and management, the MPF project was hugely successfirl and won the Project Management Institute's coveted "Project of the Year ,{ward" for 1998 (Project lv{anagement Institute, n.d.). Many factors led to the project's success. -

Sojourner on Mars and Lessons Learned for Future Planetary Missions

981695 Sojourneron M arsand Lessons Learned forFuturePlanetary Rovers Brian W ilcox and Tam Nguyen NASA's JetPropulsion Laboratory C opyright© 1997 SocietyofAutom otive Engineers,Inc. ABSTRACT The sitelocations w ere designated by a hum an operator using engineering datacollected during previous On July 4, 1997, the M arsPathfinder spacecraft traversals and end-of-solstereo im ages captured by the successfullylanded on M arsinthe Ares Vallislanding lander IMP (Im ager for M arsPathfinder) cam eras. site and deployed an 11.5-kilogram m icrorover nam ed During the traversalsthe rover autonom ouslyavoided Sojourner.Thismicrorover accom plished itsprimary rock,drop-off,and slope hazards. Itchanged its course mission objectives inthe first 7 days, and continued to toavoidthese hazards and turned back tow ardits goals operatefora totalof83 sols(1 sol= M ars day = 1 Earth w henever the hazards w erenolonger inits w ay. The day + ~24 m ins)untilthe landerlostcom m unication w ith rover used "dead reckoning" counting w heel turns and Earth, probably due tolander batteryfailure. The using on-boardrate sensorsestimate position. Although microrover navigated to m any sites surrounding the the rover telem etryrecorded itsresponses to hum an lander, and conducted various science and technology driver com m ands in detail,the vehicle'sactualpositions experim entsusing itson-boardinstrum ents. were not know n untilexamination of the lander stereo im ages at the end of the sol.Acollection of stereo Inthis paper,the rover navigation perform ance is im ages containing rover tracks allow s reconstruction of analyzed on the basisofreceived rovertelem etry, rover the rover physicaltraversalpaththoughoutthe m ission. uplink com m ands and stereo im ages captured by the Since the primary purpose for a robotic vehicleon lander cam eras. -

What Makes a Rover?

What Makes a Rover? WHAT MAKES A ROVER? HOW DO SCIENTISTS USE THEM TO DISCOVER FAR AWAY PLACES? Use this activity guide to explore rovers that humans have built, then design one of your own to explore a location in the solar system! HOW DOES IT WORK? SKILLS Complete the activities in this guide to research, design, build, and test Asking Questions your own rovers! Use the instructions on the following pages to Developing and Using guide your research and design process. Directions for each activity Models are on the following pages: Rover Research (pages 2-3), Design Planning and Carrying out Investigations Challenge: Rovers (pages 4-5), Rover Races (page 6). Analyzing and Interpreting Data Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information CONCEPTS Cause and Effect Structure and Function STANDARDS More information regarding the NGSS standards of this activity is available at the end of this guide (page 9). WHAT’S A ROVER? Stay Connected! When humans want to learn about other planets or objects in the solar Be sure to share your system, they can use tools like telescopes, satellites, and rovers. A research, designs, and rover is a small, mobile robot that scientists send to moons and planets prototypes with us online to land on their surfaces and explore. Rovers can take pictures and by tagging collect information about the planet by taking temperature readings, @chabotspace, or using rock, and soil samples. The rovers then send this information back to the hashtags scientists on earth through radio signals. Rovers can help scientists learn #ChabotRovers and about faraway places without having to send people to space, which #LearningLaunchpad can be tricky! ROVER RESEARCH NASA uses rovers to explore other places in our solar system. -

Mars Science Laboratory Landing

PRESS KIT/JULY 2012 Mars Science Laboratory Landing Media Contacts Dwayne Brown NASA’s Mars 202-358-1726 Steve Cole Program 202-358-0918 Headquarters [email protected] Washington [email protected] Guy Webster Mars Science Laboratory 818-354-5011 D.C. Agle Mission 818-393-9011 Jet Propulsion Laboratory [email protected] Pasadena, Calif. [email protected] Science Payload Investigations Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer: Ruth Ann Chicoine, Canadian Space Agency, Saint-Hubert, Québec, Canada; 450-926-4451; [email protected] Chemistry and Camera: James Rickman, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, N.M.; 505-665-9203; [email protected] Chemistry and Mineralogy: Rachel Hoover, NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, Calif.; 650-604-0643; [email protected] Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons: Igor Mitrofanov, Space Research Institute, Moscow, Russia; 011-7-495-333-3489; [email protected] Mars Descent Imager, Mars Hand Lens Imager, Mast Camera: Michael Ravine, Malin Space Science Systems, San Diego; 858-552-2650 extension 591; [email protected] Radiation Assessment Detector: Donald Hassler, Southwest Research Institute; Boulder, Colo.; 303-546-0683; [email protected] Rover Environmental Monitoring Station: Luis Cuesta, Centro de Astrobiología, Madrid, Spain; 011-34-620-265557; [email protected] Sample Analysis at Mars: Nancy Neal Jones, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.; 301-286-0039; [email protected] Engineering Investigation MSL Entry, Descent and Landing Instrument Suite: Kathy Barnstorff, NASA Langley Research Center, Hampton, Va.; 757-864-9886; [email protected] Contents Media Services Information. -

Summary of Results from the Risk Management Program for the Mars Microrover Flight Experiment

Summary of Results from the Risk Management program for the Mars Microrover Flight Experiment Robert Shishko, Ph.D. and Jacob R. Matijevic, Ph.D. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology 4800 Oak Grov'e Drive, Pasadena CA 91109 volume, mass, and power for both the microrover Abstract. On 4 July 1997, the Mars and its instrument (APXS) payload, microrover Pathfinder landed on the surface of Mars carrying interfaces with the Pathfinder spacecraft, and use of the first planetary rover, known as the Sojourner. some commercial and MiI-Spec parts. Operations Formally known as the Microrover Flight risks arose because of an unknown landed Experiment (MFEX), the Sojourner was a low cost, configuration for the lander, use of new approaches high-risk technology demonstration, in which new to command, control, and communication, and risk management techniques were tried. This paper uncertain environmental conditions. summarizes the activities and results of the effort to conduct a low-cost, yet meaningful risk This paper summarizes the activities and management program for the MFEX. The specific results of the effort to conduct a low-cost, yet activities focused on cost, performance, schedule, meaningful risk management program for the and operations risks. Just as the systems MFEX, which was originally designated as a high- engineering process was iterative and produced risk (Class D) payload. The specific objectives of successive refinements of requirements, designs, the MFEX risk management effort were: etc., so was the risk management process. Qualitative risk assessments were performed first (a) Define and implement a risk to gain some insights for refining the microrover management process tailored to design and operations concept. -

NASA's Mars Rovers Have Always Posed Fascinating Power and Circuitry Challenges, and So It Is with the Mars 2020 Rover Now In

CASE STUDY ELECTRONICS For Mars 2020, circuitry is a key NASA’s Mars rovers have always posed fascinating power and circuitry challenges, and so it is with the Mars 2020 rover now in assembly at the NASA-funded Jet Propulsion Lab in California. Dale McKeeby of California- based Pioneer Circuits explains the rover’s innovative circuitry scheme. BY DALE MCKEEBY 16 | APRIL 2018 | aerospaceamerica.aiaa.org ur staff here at Pioneer Circuits began 2-meter-long arm to gather pellet-like core samples working on Mars rovers in 1994 when of Martian soil and rock with a drill, and take pic- we received a request from NASA’s Jet tures of the samples. Overall, the rover will have 23 Propulsion Lab in California to build cameras compared to Curiosity’s 17. Specifi cally, a circuitry for an upcoming mission now mostly titanium mast will rise from its chassis holding Oknown as Mars Pathfi nder. The mission’s 10.6-kilo- Mastcam-Z, a collection of cameras for zooming in gram rover, called Sojourner, was the fi rst ever on the on terrain, taking 3-D pictures and panoramic shots. Martian surface, but when we joined the project, JPL These devices will need to receive power from the thought mass limits would rule out a rover in favor rover’s two batteries, and commands from the rover’s of a stationary lander. The problem was the weight brain consisting of two Rover Compute Elements. of the hard wiring necessary to deliver power to the Images must also fl ow back to the brain for navi- rover’s electronics, including its visual system and gation and for transmission to Earth.