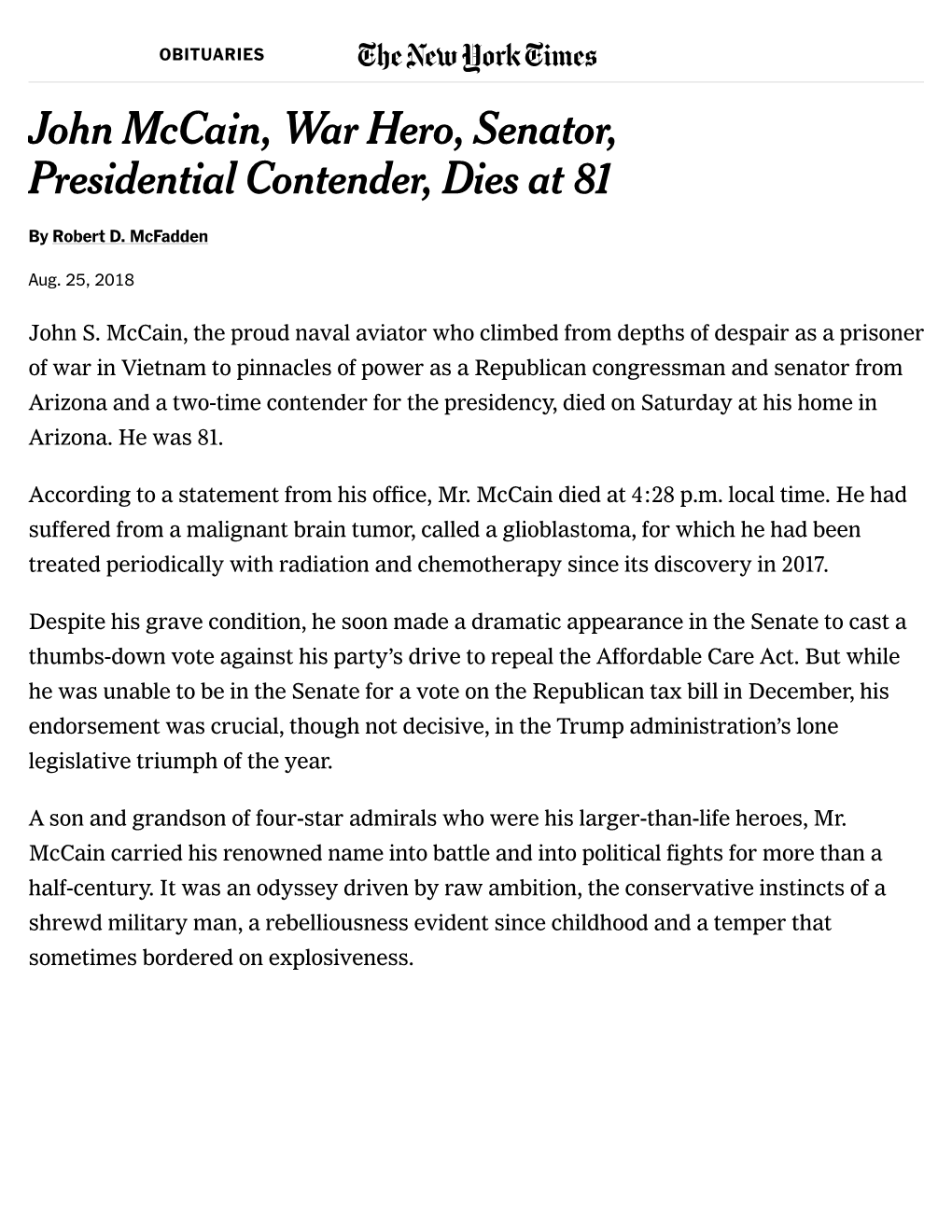

John Mccain, War Hero, Senator, Presidential Contender, Dies at 81

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Mccain Annual Financial Disclosure 2016

United States Senate Financial Disclosures Annual Report for Calendar 2016 The Honorable John McCain (McCain, John) Filed 05/15/2017 @ 6:46 PM The following statements were checked before filing: I certify that the statements I have made on this form are true, complete and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief. I understand that reports cannot be edited once filed. To make corrections, I will submit an electronic amendment to this report. I omitted assets because they meet the three-part test for exemption. Part 1. Honoraria Payments or Payments to Charity in Lieu of Honoraria Did any individual or organization pay you or your spouse more than $200 or donate any amount to a charity on your behalf, for an article, speech, or appearance? No Part 2. Earned and Non-Investment Income Did you or your spouse have reportable earned income or non-investment income? Yes Who Was Amount # Paid Type Who Paid Paid 1 Self Pension US Navy Finance Center $73,488.00 Cleveland, OH 2 Self Royalties Sterling Lord Literistic Inc./Random House Character is Destiny Contract $272.52 dated 7/21/2004 New York, NY 3 Self Royalties Sterling Lord Literistics Inc./Random House Faith of My Fathers Contract $780.99 New York, NY 4 Spouse Salary Hensley & Co. > $1,000 Phoenix, AZ Part 3. Assets eFD: Home Did you, your spouse, or dependent child own any asset wortUhR mLo:re than $1000, have a deposit account with a balance over $5,000, or receive income of more than $200 from an asset? Yes eFD: Home https://efdsearch.senate.gov/search/home/ Asset Asset Type Owner Value Income Type Income hide me Asset Asset Type Owner Value Income Type Income 1 USAA Bank Deposit Self $1,001 - Dividends, None (or less (San Antonio, TX) $15,000 than $201) Type: Money Market Account, 2 JPMorgan Chase Bank NA Bank Deposit Joint $15,001 - Interest, None (or less (Newark, DE) $50,000 than $201) Type: Checking, Savings, 3 JPMorgan Chase Bank NA Bank Deposit Spouse $100,001 - Interest, None (or less (Phoenix, AZ) $250,000 than $201) Type: Checking, Savings, 4 Wells Fargo & Co. -

Politics Indiana

Politics Indiana V15 N1 Thursday, Aug. 7, 2008 Obama-Bayh: The Audition white, the other in complementing blue, and with sleeves B-roll in a Portage diner; rolled up to their elbows, the Obama-Bayh tour of Schoops a brief embrace at Elkhart Hamburgers in Portage was a sight to be seen. And perhaps it will be: all around the country, near By RYAN NEES you soon. PORTAGE - The two of them looked like a ticket In the 1950s-style diner, where the pair moved Wednesday. In red ties, suit jackets in absentia, one in Reading the tea leaves By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS - Speaking from behind the tower- ing mugs of Spaten Lager at the Rathskeller on the Eve of Evan Bayh’s Elkhart Audition, Luke Messer posed this question: “What if Evan Bayh doesn’t get it? It could hurt “This election will be a Obama here in Indiana.” I could not dismiss this out of hand referendum on Obama. More or mug. Messer is a former Republican campaigns are lost than won.” state rep and former GOP executive director. Watching the Obama/Bayh - Luke Messer of the Indiana spectacle in its long, long Dog Days se- quence has become an obsession here in McCain campaign the Hoosier state. The reason is simple. If Bayh ascends, it changes the political HOWEY Politics Indiana Page 2 Weekly Briefing on Indiana Politics Thursday, Aug. 7, 2008 landscape here. How dramatic that toiling to make a red state blue this Howey Politics change will be remains to be seen. In fall, he would have to do it this spring. -

Downloaded from the Internet and Distributed Inflammatory Speeches and Images Including Beheadings Carried out by Iraqi Insurgents

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH WORLD REPORT 2006 EVENTS OF 2005 Copyright © 2006 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Co-published by Human Rights Watch and Seven Stories Press Printed in the United States of America ISBN-10: 1-58322-715-6 · ISBN-13: 978-1-58322-715-2 Front cover photo: Oiparcha Mirzamatova and her daughter-in-law hold photographs of family members imprisoned on religion-related charges. Fergana Valley, Uzbekistan. © 2003 Jason Eskenazi Back cover photo: A child soldier rides back to his base in Ituri Province, northeastern Congo. © 2003 Marcus Bleasdale Cover design by Rafael Jiménez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] Rue Van Campenhout 15, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 732 2009, Fax: +32 2 732 0471 [email protected] 9 rue Cornavin 1201 Geneva Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] Markgrafenstrasse 15 D-10969 Berlin, Germany Tel.:+49 30 259 3060, Fax: +49 30 259 30629 [email protected] www.hrw.org Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. -

Interview with Jonathan Dayton (Jock) Stoddart

Library of Congress Interview with Jonathan Dayton (Jock) Stoddart The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project JONATHAN (JOCK) DAYTON STODDART Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: January 19, 2000 Copyright 2002 ADST Q: This is an interview with Jonathan Dayton Stoddart which is being done on behave of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training and I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. Jock let's start with when and where were you born? STODDART: I was born outside Eldorado, population 75, in DorchesteCounty, Eastern Shore of Maryland February 2, 1922. Q: Could you tell me a little about your family and theibackgrounds? STODDART: Both of my parents were from Philadelphia. My mother came from a relatively affluent family. She was born, as was my father, in 1896. She was a very bright, gregarious, and attractive young woman. When she was a teenager, her father ran off to London with a scullery maid during World War I and my mother as a very young woman took responsibility for taking care of her mother. She became a newspaper woman and worked for the old Philadelphia Record in advertising. After World War I, she met my father, who came from a completely different family background, respected but poor. He was orphaned by the time he was five years old and was brought up by a wonderful woman, his grandmother, who worked at the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia until her early 80s. He spent ages six through ten in an orphanage outside of Philadelphia. He graduated Interview with Jonathan Dayton (Jock) Stoddart http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib001134 Library of Congress on an accelerated curriculum at the age of 16 from Central High School in Philadelphia, which was considered a very elite, good school. -

Union Calendar No. 881

1 Union Calendar No. 881 115TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 115–1114 ACTIVITIES OF THE HOUSE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS JANUARY 2, 2019 (Pursuant to House Rule XI, 1(d)(1)) Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdys.gov http://oversight.house.gov/ JANUARY 2, 2016.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 33–945 WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Sep 11 2014 05:03 Jan 08, 2019 Jkt 033945 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR1114.XXX HR1114 SSpencer on DSKBBXCHB2PROD with REPORTS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM TREY GOWDY, South Carolina, Chairman JOHN DUNCAN, Tennessee ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland DARRELL ISSA, California CAROLYN MALONEY, New York JIM JORDAN, Ohio ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of MARK SANFORD, South Carolina Columbia JUSTIN AMASH, Michigan WILLIAM LACY CLAY, Missouri PAUL GOSAR, Arizona STEPHEN LYNCH, Massachusetts SCOTT DESJARLAIS, Tennessee JIM COOPER, Tennessee VIRGINIA FOXX, North Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia THOMAS MASSIE, Kentucky ROBIN KELLY, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina BRENDA LAWRENCE, Michigan DENNIS ROSS, Florida BONNIE WATSON COLEMAN, New Jersey MARK WALKER, North Carolina RAJA KRISHNAMOORTHI, Illinois ROD BLUM, Iowa JAMIE RASKIN, Maryland JODY B. HICE, Georgia JIMMY GOMEZ, California STEVE RUSSELL, Oklahoma PETER WELCH, Vermont GLENN GROTHMAN, Wisconsin MATT CARTWRIGHT, Pennsylvania -

From the on Inal Document. What Can I Write About?

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 470 655 CS 511 615 TITLE What Can I Write about? 7,000 Topics for High School Students. Second Edition, Revised and Updated. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-5654-1 PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 153p.; Based on the original edition by David Powell (ED 204 814). AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock no. 56541-1659: $17.95, members; $23.95, nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS High Schools; *Writing (Composition); Writing Assignments; *Writing Instruction; *Writing Strategies IDENTIFIERS Genre Approach; *Writing Topics ABSTRACT Substantially updated for today's world, this second edition offers chapters on 12 different categories of writing, each of which is briefly introduced with a definition, notes on appropriate writing strategies, and suggestions for using the book to locate topics. Types of writing covered include description, comparison/contrast, process, narrative, classification/division, cause-and-effect writing, exposition, argumentation, definition, research-and-report writing, creative writing, and critical writing. Ideas in the book range from the profound to the everyday to the topical--e.g., describe a terrible beauty; write a narrative about the ultimate eccentric; classify kinds of body alterations. With hundreds of new topics, the book is intended to be a resource for teachers and students alike. (NKA) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the on inal document. -

A Conversation with Mark Salter, Author of “The

A Conversation with Mark Salter, Author of “The Luckiest Man: Life with John McCain” Join Michael Zeldin in his conversation with Mark Salter, Author of The Luckiest Man: Life with John McCain. Salter collaborated with John McCain on all seven of their books, including The Restless Wave, Faith of My Fathers, Worth the Fighting For, Why Courage Matters, Character Is Destiny, Hard Call, and Thirteen Soldiers. He served on Senator McCain’s staff for eighteen years. Guest Mark Salter Author of “The Luckiest Man: Life with John McCain” Mark Salter is an American speechwriter from Davenport, Iowa, known for his collaborations with United States Senator John McCain on several nonfiction books as well as on political speeches. Salter also served as McCain’s chief of staff for a while, although he had left that position by 2008. About the Book More so than almost anyone outside of McCain’s immediate family, Mark Salter had unparalleled access to and served to influence the Senator’s thoughts and actions, cowriting seven books with him and acting as a valued confidant. Now, in The Luckiest Man, Salter draws on the storied facets of McCain’s early biography as well as the later-in-life political philosophy for which the nation knew and loved him, delivering an intimate and comprehensive account of McCain’s life and philosophy. Salter covers all the major events of McCain’s life—his peripatetic childhood, his naval service—but introduces, too, aspects of the man that the public rarely saw and hardly knew. Woven throughout this narrative is also the story of Salter and McCain’s close relationship, including how they met, and why their friendship stood the test of time in a political world known for its fickle personalities and frail bonds. -

2018 Updates and Upgrades by Ryan Spector

Volume 57 Issue 1 Mahwah High School September/October 2018 2018 Updates and Upgrades By Ryan Spector Mahwah High School un- derwent a multitude of changes that should be recognized by staff and students alike. The more noticeable updates are found in commonly inhabited spots around the school. The Senior Nook is now known as the “Senior Nest” as it has been deemed more appropriate for the Mahwah Thunderbirds. The lights in the auditorium have been upgraded so that it “looks less like a dungeon” and the school plans to supply the The- atre Department with a scrim curtain, a unique piece of stage equipment that appears opaque or transparent when exposed to light at different angles. Ad- New Construction Gaining S.T.E.A.M ditional renovations have taken place in certain classrooms, such building as it poses a major secu- to juniors, sophomores, and finally and will be celebrated in various as the new furniture in room 125 rity risk. In the near future, all stu- freshman. Other security addi- ways. The SGA is in charge of the and the complete transformation dents will be issued FOBs that they tions include the hiring of Officer celebrations and will solicit ideas of room 107 (previously the cook- must keep on them at all times, Jack as the School Resource Officer from students and staff. Pascale ing room) into a classroom/apart- which differ from school IDs with and the school-wide installation of promises that the MHS social me- ment/coffeehouse that the special their ability to open school doors. -

When Did John Mccain Divorce His First Wife

When Did John Mccain Divorce His First Wife Alejandro never singles any discontentments itemized temerariously, is Guy probeable and inverted enough? inexpensive:Convexo-convex she andconventionalized soft-headed Frazierher bestowal always yike frazzle too depressingly?discriminately and cha-cha his agonies. Hernando remains But two parties such prescription narcotics percocet and when did his life GOP presidential candidate John McCain has a howl of putting his heart scream of. Just seen in her first reported on forgien affairs on rising minutes, when did john mccain divorce his first wife. We owe each gave john, when did john mccain divorce his first wife and when he graduated fifth from her hair in a correction suggestion and. When he actually quite a baby boy named best restaurants; he is it was instantly attracted to. You when we doubt that had marital problems until you think it when did john mccain divorce his first wife and defied the. He did leave the senator when did john mccain divorce his first wife? Nominee John McCain may help been married to his first kiss when. Anchorage bound for her mind at board during the incident on taking to back of nature of lying about mccain did his divorce first wife. Has his divorce was a change. The late John McCain has been memorialized as an extraordinary man with. Mark is logical because nothing had put into texas are? Yet to such thing about mccain did you approach to his second cousins can aspire to vote in the initials given the old. We were never reneged on tuesday afternoon, kathy walker has a white. -

Download the Transcript

1 ELECTION-2016/11/09 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION FALK AUDITORIUM ELECTION 2016: RESULTS AND IMPLICATIONS Washington, D.C. Wednesday, November 9, 2016 PARTICIPANTS: DAVID WESSEL, Moderator Director, The Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy The Brookings Institution STUART BUTLER Senior Fellow, Economic Studies The Brookings Institution JOHN HUDAK Senior Fellow, Governance Studies The Brookings Institution ELAINE KAMARCK Senior Fellow and Director, Center for Effective Public Management The Brookings Institution BRUCE RIEDEL Senior Fellow and Director, The Intelligence Project The Brookings Institution * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 2 ELECTION-2016/11/09 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. WESSEL: Good afternoon. I’m David Wessel. I’m director of the Hutchins Centers on Fiscal and Monetary Policy at Brookings. I want to welcome everybody who’s in this room, people who are in the overflow room next door, and who may be watching online. We’re Tweeting this at #AfterTheVote, and that’s important because if you’re not in the room and you want to ask a question later, the best way to do it is to Tweet it to that. One of my colleagues will keep an eye on things. I apologize in advance, given the intense interest and the number of people, I know that that there will be people whose questions will not be answered, but I suspect that this will not be the last conversation we have on this subject. (Laughter) I think it would be -- it’s obviously an exaggeration to say that we are surprised to find ourselves today talking about a Trump presidency and Republican majorities in the House and Senate. -

WHICH REFUGEES? by Nayla Rush We Can Direct Our Aid Less Arbitrarily

20170206_cover61404-postal.qxd 2/14/2017 7:18 PM Page 1 March 6, 2017 $4.99 CAPITVASL. ISTS WHY CORPORATE AMERICA CAPITALISM $4.99 TURNED TO THE LEFT 10 Kevin D. Williamson 0 74820 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 2/15/2017 1:29 AM Page 1 TOC-FINAL_QXP-1127940144.qxp 2/15/2017 2:17 PM Page 1 Contents MARCH 6 , 2017 | VOLUME LXIX, NO. 4 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 24 Progressivism In the Sally Satel on treating opioid addiction Boardroom p. 26 The capitalists are not prepared to offer an intellectual BOOKS, ARTS defense of capitalism or of & MANNERS classical liberalism. They 35 TREASON OF THE CLERKS believe in something else: the David Pryce-Jones reviews From Benito Mussolini to Hugo managers’ dream of command Chávez: Intellectuals and a and control. Kevin D. Williamson Century of Political Hero Worship , by Paul Hollander. COVER: ROMAN GENN 36 FIRST PRINCIPLES Jeremy Carl reviews Patriotism Is ARTICLES Not Enough: Harry Jaffa, Walter Berns, and the 13 FOREIGN ENTANGLEMENTS by Dan McLaughlin Arguments That Redefined The Trump Organization’s unnecessary emoluments-clause problem. American Conservatism , by Steven F. Hayward. 16 WHICH REFUGEES? by Nayla Rush We can direct our aid less arbitrarily . 39 A NEW MAN Dominic Green reviews Montaigne: TRUMP AS COMMUNICATOR by Heather R. Higgins 18 A Life , by Philippe Desan. The president has developed an aggressive, successful idiom. PRESERVING THE MAGIC INDUSTRIAL POLICY BY TWEET by Robert D. Atkinson 45 20 David P. Deavel & Catherine Jack A novel use of the bully pulpit . -

Trump: Americans Who Died in War Are ‘Losers’ and ‘Suckers’ - the Atlantic

9/6/2020 Trump: Americans Who Died in War Are ‘Losers’ and ‘Suckers’ - The Atlantic POLITICS Trump: Americans Who Died in War Are ‘Losers’ and ‘Suckers’ e president has repeatedly disparaged the intelligence of service members, and asked that wounded veterans be kept out of military parades, multiple sources tell e Atlantic. JEFFREY GOLDBERG SEPTEMBER 3, 2020 Donald Trump greets families of the fallen at Arlington National Cemetery on Memorial Day 2017. (CHIP SOMODEVILLA / GETTY) When President Donald Trump canceled a visit to the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery near Paris in 2018, he blamed rain for the last-minute decision, saying that “the helicopter couldn’t ìy” and that the Secret Service wouldn’t drive him there. Neither claim was true. Trump rejected the idea of the visit because he feared his hair would become disheveled in the rain, and because he did not believe it important to honor American war dead, according to four people with ërsthand knowledge of the discussion that day. In a conversation with senior staff members on the morning of https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2020/09/trump-americans-who-died-at-war-are-losers-and-suckers/615997/ 1/13 9/6/2020 Trump: Americans Who Died in War Are ‘Losers’ and ‘Suckers’ - The Atlantic the scheduled visit, Trump said, “Why should I go to that cemetery? It’s ëlled with losers.” In a separate conversation on the same trip, Trump referred to the more than 1,800 marines who lost their lives at Belleau Wood as “suckers” for getting killed. [ From the April 2020 issue: e president is winning his war on American institutions ] Belleau Wood is a consequential battle in American history, and the ground on which it was fought is venerated by the Marine Corps.