I Am a Monster: an Exploration of the Self Through Examination of Fragmented Identity Or Mary Shelley’S Frankenstein Becomes a Guide for Self-Reflection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960S and Early 1970S

TV/Series 12 | 2017 Littérature et séries télévisées/Literature and TV series Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.2200 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Dennis Tredy, « Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s », TV/Series [Online], 12 | 2017, Online since 20 September 2017, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 ; DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.2200 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series o... 1 Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy 1 In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, in a somewhat failed attempt to wrestle some high ratings away from the network leader CBS, ABC would produce a spate of supernatural sitcoms, soap operas and investigative dramas, adapting and borrowing heavily from major works of Gothic literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The trend began in 1964, when ABC produced the sitcom The Addams Family (1964-66), based on works of cartoonist Charles Addams, and CBS countered with its own The Munsters (CBS, 1964-66) –both satirical inversions of the American ideal sitcom family in which various monsters and freaks from Gothic literature and classic horror films form a family of misfits that somehow thrive in middle-class, suburban America. -

Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman's Film Score Bride of Frankenstein

This is a repository copy of Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118268/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McClelland, C (Cover date: 2014) Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. Journal of Film Music, 7 (1). pp. 5-19. ISSN 1087-7142 https://doi.org/10.1558/jfm.27224 © Copyright the International Film Music Society, published by Equinox Publishing Ltd 2017, This is an author produced version of a paper published in the Journal of Film Music. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Paper for the Journal of Film Music Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein Universal’s horror classic Bride of Frankenstein (1935) directed by James Whale is iconic not just because of its enduring images and acting, but also because of the high quality of its score by Franz Waxman. -

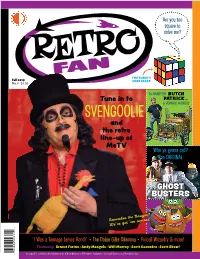

SVENGOOLIE and the Retro Line-Up of Metv Who Ya Gonna Call? the ORIGINAL

Are you too square to solve me? THE RUBIK'S Fall 2019 CUBE CRAZE No. 6 $8.95 The MUNSTERS’ BUTCH Tune in to PATRICK… & HORRIFIC HOTRODS SVENGOOLIE and the retro line-up of MeTV Who ya gonna call? The ORIGINAL GHOST BUSTERS Remember the Naugas? We’ve got ’em covered 2 2 7 3 0 0 “I Was a Teenage James Bond!” • The Dobie Gillis Dilemma • Pinball Wizardry & more! 8 5 6 2 Featuring Ernest Farino • Andy Mangels • Will Murray • Scott Saavedra • Scott Shaw! 8 Svengoolie © Weigel Broadcasting Co. Ghost Busters © Filmation. Naugas © Uniroyal Engineered Products, LLC. 1 The crazy cool culture we grew up with CONTENTS Issue #6 | Fall 2019 40 51 Columns and Special Features Departments 3 2 Retro Television Retrotorial Saturday Nights with 25 Svengoolie 10 RetroFad 11 Rubik’s Cube 3 Andy Mangels’ Retro Saturday Mornings 38 The Original Ghost Busters Retro Trivia Goldfinger 21 43 Oddball World of Scott Shaw! 40 The Naugas Too Much TV Quiz 25 59 Ernest Farino’s Retro Retro Toys Fantasmagoria Kenner’s Alien I Was a Teenage James Bond 21 74 43 Celebrity Crushes Scott Saavedra’s Secret Sanctum 75 Three Letters to Three Famous Retro Travel People Pinball Hall of Fame – Las Vegas, Nevada 51 65 Retro Interview 78 Growing Up Munster: RetroFanmail Butch Patrick 80 65 ReJECTED Will Murray’s 20th Century RetroFan fantasy cover by Panopticon Scott Saavedra The Dobie Gillis Dilemma 75 11 RetroFan™ #6, Fall 2019. Published quarterly by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. Michael Eury, Editor-in-Chief. John Morrow, Publisher. -

Sky Pilot, How High Can You Fly - Not Even Past

Sky Pilot, How High Can You Fly - Not Even Past BOOKS FILMS & MEDIA THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN BLOG TEXAS OUR/STORIES STUDENTS ABOUT 15 MINUTE HISTORY "The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Tweet 19 Like THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Sky Pilot, How High Can You Fly by Nathan Stone Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the Confederacy” I started going to camp in 1968. We were still just children, but we already had Vietnam to think about. The evening news was a body count. At camp, we didn’t see the news, but we listened to Eric Burdon and the Animals’ Sky Pilot while doing our beadwork with Father Pekarski. Pekarski looked like Grandpa from The Munsters. He was bald with a scowl and a growl, wearing shorts and an official camp tee shirt over his pot belly. The local legend was that at night, before going out to do his vampire thing, he would come in and mix up your beads so that the red ones were in the blue box, and the black ones were in the white box. Then, he would twist the thread on your bead loom a hundred and twenty times so that it would be impossible to work with the next day. And laugh. In fact, he was as nice a May 06, 2020 guy as you could ever want to know. More from The Public Historian BOOKS America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States by Erika Lee (2019) April 20, 2020 More Books The Munsters Back then, bead-craft might have seemed like a sort of “feminine” thing to be doing at a boys’ camp. -

Fotp18 Mad Science Cinema Film Series Flyer

Mad Science Cinema Friday, September 14 · 12:30 p.m. One Book, Frankenstein One Community 2018 This is the original full‐length feature film adaptation of Mary Shelley’s novel, and the one that gave us the visual image of the Monster that we all Film Series recognize. Colin Clive stars as Dr. Frankenstein, with Boris Karloff as his Creature. People all over the world are reading 1931 / 70 min. / Not rated / © Universal Frankenstein this year in celebration of Friday, September 28 · 12:30 p.m. the 200th anniversary of its publication, and The Bride of Frankenstein Fayette County is getting Clive and Karloff return in this sequel in which the scientist builds his in on the fun! Creature a mate. Elsa Lanchester plays dual roles, appearing both as the The Fayette County Public Bride and as author Mary Shelley, in a story‐within‐a‐story format. Library, in partnership with 1935 / 75 min. / Not rated / © Universal the Friends of the Fayette County Public Library, presents a series of Saturday, September 29 · CREATURE TRIPLE FEATURE free community activities Frankenstein: 10:00 a.m. focusing on Repeat Screenings! Frankenstein The Bride of Frankenstein: 12:00 noon by Mary Shelley. A.I. Artificial Intelligence: 3:00 p.m. The Fayette on the Page 2018 Film Series Friday, October 5 · 12:30 p.m. offers a collection of cinematic stories A.I. Artificial Intelligence influenced by Shelley’s tale Frankenstein has influenced numerous stories of the ramifications of of Victor Frankenstein and his unfortunate Creature. manmade creatures. Here is one that will definitely make you think. -

La Novia De Frankenstein La Rara Proeza De Mejorar La Obra Inicial Y Acercarse Mucho Al Nivel De Lo Que Se Puede Entender Como Una Obra Maestra

Una de las obras cumbre del género fantástico FICHA TÉCNICA: Título original: Bride of Frankenstein Nacionalidad: EEUU Año: 1935 Dirección: James Whale Guión: William Hurlbut, John Balderston (sugerido por la novela Frankenstein o el moderno Prometeo de Mary W. Shelley) Producción: Carl Laemmle Jr. Dirección de Fotografía: John Mescall Montaje: Ted Kent Dirección Artística: Charles D. Hall Música: Franz Waxman Maquillaje: Jack Pierce Efectos Especiales: John P. Fulton Reparto: Boris Karloff ( El Monstruo ), Colin Clive (Barón Henry Frankenstein ), Valerie Hobson ( Eli- zabeth ), Ernest Thesiger ( Dr. Septimus Pretorius ), Elsa Lanchester ( Mary W. Shelley / Compañera del Monstruo ), Gavin Gordon ( Lord Byron ), Douglas Walton ( Percy Bysshe Shelley ), Una O'Connor (Minnie ), E.E. Clive ( Burgomaestre ), Lucien Prival (Albert, el Mayordomo ), Dwight Frye ( Karl, el Jo- robado ) Duración: 75 min. (B/N) SINOPSIS: Durante su convalecencia, Henry Frankenstein recibe la visita de un hombre extravagante que dice ser el Dr. Pretorious , quien le pide que colabore con él en sus experimentos para la creación de la vida. Con objeto de animarle a ello, Pretorious le muestra una colección de homúnculos que reviven durante unos segundos un mundo mágico ante la mirada fascinada de Henry . No obstante, Frankenstein no se deja tentar y rehúsa el ofrecimiento. Pero Pretorious contará con una baza inesperada a su favor: El Monstruo . Juntos obligan a Henry a crear una mujer que sea la compañera del monstruo. HOJA INFORMAT IVA Nº 68 Abril 2005 COMENTARIOS: Cuatro años después de su éxito inicial con El Dr. Frankenstein y tras haber rodado, entre otras, la magnífica adaptación cinematográfica de la novela El Hombre Invisible de H.G. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Wednesday, March 18, 2009 2:36:33PM School: Churchland Academy Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 9318 EN Ice Is...Whee! Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 9340 EN Snow Joe Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 36573 EN Big Egg Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 99 F 9306 EN Bugs! McKissack, Patricia C. LG 0.4 0.5 69 F 86010 EN Cat Traps Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 95 F 9329 EN Oh No, Otis! Frankel, Julie LG 0.4 0.5 97 F 9333 EN Pet for Pat, A Snow, Pegeen LG 0.4 0.5 71 F 9334 EN Please, Wind? Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 55 F 9336 EN Rain! Rain! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 63 F 9338 EN Shine, Sun! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 66 F 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 171 F 9305 EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Stevens, Philippa LG 0.5 0.5 100 F 7255 EN Can You Play? Ziefert, Harriet LG 0.5 0.5 144 F 9314 EN Hi, Clouds Greene, Carol LG 0.5 0.5 58 F 9382 EN Little Runaway, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 196 F 7282 EN Lucky Bear Phillips, Joan LG 0.5 0.5 150 F 31542 EN Mine's the Best Bonsall, Crosby LG 0.5 0.5 106 F 901618 EN Night Watch (SF Edition) Fear, Sharon LG 0.5 0.5 51 F 9349 EN Whisper Is Quiet, A Lunn, Carolyn LG 0.5 0.5 63 NF 74854 EN Cooking with the Cat Worth, Bonnie LG 0.6 0.5 135 F 42150 EN Don't Cut My Hair! Wilhelm, Hans LG 0.6 0.5 74 F 9018 EN Foot Book, The Seuss, Dr. -

Fracking (With) Post-Modernism, Or There's a Lil' Dr Frankenstein in All

1 Fracking (with) post-modernism, or there’s a lil’ Dr Frankenstein in all of us by Bryan Konefsky Since the dawn of (wo)mankind we humans have had the keen, pro-cinematic ability to assess our surroundings in ways not unlike the quick, rack focus of a movie camera. We move fluidly between close examination (a form of deconstruction) to a wide-angle view of the world (contextualizing the minutiae of our dailiness within deep philosophical inquiries about the nature of existence). To this end, one could easily infer that Dziga Vertov’s kino-eye might be a natural outgrowth of human evolution. However, we should be mindful of obvious and impetuous conclusions that seem to lead – superficially – to the necessity of a kino-prosthesis. In terms of a kino-prosthesis, the discomfort associated with a camera-less experience is understood, especially in a world where, as articulated so well by thinkers such as Sherry Turkle or Marita Sturken, one impulsively records information as proof of experience (see Turkle’s Alone Together: Why We Expect More From Technology and Less From Each Other and Sturken’s Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture). The unsettling nature of a camera-less experience reminds me of visionary poet Lisa Gill (see her text Caput Nili), who once told me about a dream in which she and Orson Welles made a movie. The problem was that neither of them had a camera. Lisa is quick on her feet so her solution was simply to carve the movie into her arm. For Lisa, it is clear what the relationship is between a sharp blade and a camera, and the association abounds with metaphors and allusions to my understanding of the pro-cinematic human. -

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror Barry Keith Grant Brock University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a broad historical overview of the ideology and cultural roots of horror films. The genre of horror has been an important part of film history from the beginning and has never fallen from public popularity. It has also been a staple category of multiple national cinemas, and benefits from a most extensive network of extra-cinematic institutions. Horror movies aim to rudely move us out of our complacency in the quotidian world, by way of negative emotions such as horror, fear, suspense, terror, and disgust. To do so, horror addresses fears that are both universally taboo and that also respond to historically and culturally specific anxieties. The ideology of horror has shifted historically according to contemporaneous cultural anxieties, including the fear of repressed animal desires, sexual difference, nuclear warfare and mass annihilation, lurking madness and violence hiding underneath the quotidian, and bodily decay. But whatever the particular fears exploited by particular horror films, they provide viewers with vicarious but controlled thrills, and thus offer a release, a catharsis, of our collective and individual fears. Author Keywords Genre; taboo; ideology; mythology. Introduction Insofar as both film and videogames are visual forms that unfold in time, there is no question that the latter take their primary inspiration from the former. In what follows, I will focus on horror films rather than games, with the aim of introducing video game scholars and gamers to the rich history of the genre in the cinema. I will touch on several issues central to horror and, I hope, will suggest some connections to videogames as well as hints for further reflection on some of their points of convergence. -

Read Book the Monsters Monster

THE MONSTERS MONSTER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Patrick McDonnell | 48 pages | 06 Sep 2012 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780316045476 | English | New York, United States The Monsters Monster PDF Book More filters. After throwing dozens of quinceaneras for The Thing remains one of the most tense and heart-pounding sci-fi horror films ever made, thanks largely to its premise about an alien creature that can mimic other organic beings and assume their shape, appearance, and mannerisms. McDonnell writes a cute book about three little monsters who create their own monster, hoping he'll be really scary. They decide to create the biggest monster of all, so they get their Frankenstein on and bring a new monster to life. This is a must have and must read book. While every episode includes an unusual creature from a myth or urban legend, it's the underlying themes of family, betrayal, love, envy, greed and guilt that drive home the horror. While this episode has a real monster that lurks in the woods, the story isn't really about why or how her friend disappears. A Perfectly Messed-Up Story. The Blair Witch is at its most scary when it remains unseen and is used to psychologically torture the characters because audiences don't know who or what the Blair Witch actually is, even with the knowledge of the folklore behind it. The docudrama was created in the early '70s with a low budget, meaning that the footage was poor quality. Top-Rated Episodes S1. Daily Dead. A lovely story about meeting expectations, and friendship, and manners. -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

July11 Stat n Mod:section 6/2/2011 12:24 PM Page 401 BEATLES S THE BEATLES: YELLOW SUBMARINE MODEL KITS It’s all in the mind, y’know... Few other musical groups have left such a profound impact on worldwide culture as the Beatles. Polar Lights proudly a line of model kits commem- orating the group’s appearance in the groundbreaking animated film, Yellow Submarine. The film depicted the group on a psychedelic quest to Pepperland to free it from the music hating Blue Meanies. These easy to assemble kits feature pre-painted parts allowing even novice modelers to achieve a quality look (glue not included). Each depicts a band mem- bers as shown in the animated feature and also offers optional heads with members in their Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band personas, too! The pre-painted, easy-to- assemble kits are approximately 1/8-scale and stand about 9” tall when completed. (STK434009) (7170) (C: 1-1-3) NOTE: Available only in the United States, Canada, and U.S. Territories. RES. from Previews Vol. XXI #1 (JAN111771) JOHN LENNON (POL86012)—Model kit ......................................................$29.99 PAUL MCCARTNEY (POL85712)—Model kit ..................................................$29.99 GEORGE HARRISON (POL85812)—Model kit ...............................................$29.99 RINGO STARR (POL85912)—Model kit.........................................................$29.99 CLASSIC FILM AND TELEVISION 2011 ULY J BATMAN: CLASSIC 1966 BATMOBILE 1/25 MODEL KIT Atomic Batteries to Power! Turbines to Speed! One of the most beloved cars in televi- sion history arrives in the scale everyone craves. The 1966 Batmobile was one of the many icons to emerge from the classic Batman TV series. -

Of Thetheatre Halloween Spooktacular! Dr

VOICE Journal of the Alex Film Society Vol. 11, No. 5 October 22, 2005, 2 pm & 8 pm 10/05 of theTHEATRE Halloween Spooktacular! Dr. Shocker&Friends art Ballyhoo and part bold Pface lie, the SPOOK SHOW evolved from the death of Vaudeville and Hollywood’s need to promote their enormous slate James Whale’s of B pictures. Bride of In the 1930’s, with performance dates growing scarce, a number of magicians turned to movie Frankenstein houses for bookings. The theatre owners decided to program the magic shows with their horror movies and the SPOOK SHOW was born. Who Will Be The Bride of Frankenstein? Who Will Dare? ames Whale’s secrecy regarding class socialists. She attended Mr. Jthe casting of the Monster’s Kettle’s school in London, where she mate in Universal Studio’s follow was the only female student and up to 1931’s hugely successful won a scholarship to study dance Frankenstein set the studio’s with Isadora Duncan in France. publicity machine in motion. With the outbreak of World War I, Speculation raged over who would Lanchester was sent back to London play the newest monster with where, at the age of 11 she began Brigitte Helm, who played Maria her own “Classical Dancing Club”. in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), In 1918, she founded “The Children’s and Phyllis Brooks, a statuesque Theatre” which later morphed into illustrator’s model from New York, “The Cave of Harmony”, a late night considered the front runners. venue where Lanchester performed In spite of Universal’s publicity, one-act plays and musical revues Dr.