Methodism in Eastern Sussex 1756-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DATES of TRIALS Until October 1775, and Again from December 1816

DATES OF TRIALS Until October 1775, and again from December 1816, the printed Proceedings provide both the start and the end dates of each sessions. Until the 1750s, both the Gentleman’s and (especially) the London Magazine scrupulously noted the end dates of sessions, dates of subsequent Recorder’s Reports, and days of execution. From December 1775 to October 1816, I have derived the end dates of each sessions from newspaper accounts of the trials. Trials at the Old Bailey usually began on a Wednesday. And, of course, no trials were held on Sundays. ***** NAMES & ALIASES I have silently corrected obvious misspellings in the Proceedings (as will be apparent to users who hyper-link through to the trial account at the OBPO), particularly where those misspellings are confirmed in supporting documents. I have also regularized spellings where there may be inconsistencies at different appearances points in the OBPO. In instances where I have made a more radical change in the convict’s name, I have provided a documentary reference to justify the more marked discrepancy between the name used here and that which appears in the Proceedings. ***** AGE The printed Proceedings almost invariably provide the age of each Old Bailey convict from December 1790 onwards. From 1791 onwards, the Home Office’s “Criminal Registers” for London and Middlesex (HO 26) do so as well. However, no volumes in this series exist for 1799 and 1800, and those for 1828-33 inclusive (HO 26/35-39) omit the ages of the convicts. I have not comprehensively compared the ages reported in HO 26 with those given in the Proceedings, and it is not impossible that there are discrepancies between the two. -

Hythe Ward Hythe Ward

Cheriton Shepway Ward Profile May 2015 Hythe Ward Hythe Ward -2- Hythe Ward Foreword ..........................................................................................................5 Brief Introduction to area .............................................................................6 Map of area ......................................................................................................7 Demographic ...................................................................................................8 Local economy ...............................................................................................11 Transport links ..............................................................................................16 Education and skills .....................................................................................17 Health & Wellbeing .....................................................................................22 Housing .........................................................................................................33 Neighbourhood/community ..................................................................... 36 Planning & Development ............................................................................41 Physical Assets ............................................................................................ 42 Arts and culture ..........................................................................................48 Crime .......................................................................................................... -

The Locals Guide

The Locals Guide Contents AN INTRODUCTION TO YOUR LOCALS GUIDE 2 AT THE GALLIVANT 4 OUR BEACHES 6 EAT AND DRINK 8 SHOPPING 14 FOOD AND FARM SHOPS 18 ART, ANTIQUES AND INTERIORS 22 VINEYARDS 28 ACTIVITIES 30 WALKS, RUNNING AND CYCLING 34 CULTURE 36 USEFUL NUMBERS AND WEBSITES 44 Copyright © 2020 Harry Cragoe Photography by Paul Read and Jan Baldwin Printed on recycled paper 1 An introduction to your locals guide LOCAL PEOPLE LOCAL SHELLFISH 2 ENGLISH SEASIDE HOLIDAY Locals know best After all, they have plenty of experience. We’ve put this guide together so you get to enjoy this magical part of the world like the locals do. Imagine you were staying at a friend’s house in the country and they suggested a handful of things to do. They are always spot-on. Just right for you, and back just in time for a drink before supper. If you come away with tips, discoveries, or memories from the trips you make during your stay, it would be great if you could post them on social with the hashtag #GallivantExplore. How to use this guide Whether you have the freedom of a car or took the train down and want to stay on foot, this guide is full of trips that will work for you. Some are a stroll away. Others a half- hour drive. Short Gallivants. Long Gallivants. Sometimes you want to let go and have someone tell you where to go. That’s what our insider tips are for. Whether you need a long summer walk, a dip into the sea or want to find an Insta-friendly village – you’ll create an itinerary that works for you. -

Burial Register for St Bartholomew's Church, Burwash 1857-1888 Surname First Name 2Nd Name Sexabode When Buried Age Infants Buried by Additional Information

Burial Register for St Bartholomew's Church, Burwash 1857-1888 Surname First name 2nd name Sex Abode When buried Age Infants Buried by Additional information Russell James M Burwash 07/17/1857 64 Egerton Noakes James M Burwash 08/17/1857 73 Egerton Farmer. Smell very offensive, ought to have been buried on Saturday Relf Ann F Ticehurst Union 08/17/1857 22 Egerton Edwards Ellen Gother F Burwash 10/20/1857 Infant Egerton Pankhurst Caroline F Burwash 11/01/1857 39 Egerton Sinden Sarah F Burwash 11/29/1857 82 Egerton Heathfield Henry M Burwash 12/05/1857 49 Egerton Whybourn Rose Ann F Burwash 12/07/1857 23 Egerton Salmon Harriet F Burwash 12/07/1857 26 Egerton Mepham Mary F Burwash 12/07/1857 47 Egerton Pope Elizabeth F Burwash 12/11/1857 Infant Egerton Dann Ellen F Burwash 12/19/1857 43 Egerton Noakes John M Burwash 01/15/1858 67 Towers Isted Anna F Burwash 01/20/1858 1 Egerton Eastwood William M Burwash 01/30/1858 74 Egerton Road haulier Waterhouse Samuel M Burwash 01/30/1858 65 Egerton Sutton Hannah F Burwash 02/25/1858 94 Egerton Sweetman Mary F Salehurst 03/15/1858 39 Egerton Boorman Edward F Burwash 03/22/1858 76 Egerton Smith James M Burwash 03/29/1858 10mths Egerton Jenner Walter M Burwash 04/01/1858 Infant Egerton Barrow Richard M Burwash 04/03/1858 45 Egerton Headstone states age as 47 years. Collins Henry M Burwash 04/13/1858 55 Egerton Akhurst Alma Jenner F Burwash 05/07/1858 11 mths Egerton Aspden William M Burwash 05/24/1858 81 Egerton Jarratt Matilda F Burwash 06/03/1858 25 Egerton Wroton Mary F Burwash 06/03/1858 31 Egerton Edwards Sarah F Burwash 08/28/1858 64 Egerton Sands Stephen M Burwash 09/04/1858 68 Egerton Post mortem. -

Adherents from the Rape of Hastings and Pevensey Lowey of the Jack Cade Rebellion of 1450 Who Were Pardonned

Adherents from the Rape of Hastings and Pevensey Lowey of the Jack Cade Rebellion of 1450 who were pardonned In June 1450 Jack Cade became leader of an originally Kentish rebellion of small property holders penalised by high taxes. The rebellion spread to involve men from neighbouring counties, especially Sussex. Cade assumed the name John Mortimer and demanded the removal of several of the King’s chief ministers and the recall of Richard, Duke of York. The rebel forces defeated a royal army at Sevenoaks, Kent, on 18 June, and went on to London. There the rebels executed the lord treasurer, James Fiennes. A degree of lawlessness followed and Londoners drove the rebels from the city on 5-6 July. The government persuaded many of the rebels to disperse by offering pardons, but Cade continued his activities. He was chased down, wounded and captured at Cade Street near Heathfield, Sussex, on 12 July, and died of his wounds whilst being transported to London. The list below is of those from the Rape of Hastings and Lowey of Pevensey who had taken part in or supported the rebellion and were granted pardons. It gives a good indication of how widespread this rebellion was. It attracted adherents from across the social spectrum and involved whole communities. Undoubtedly there was no way the normal severe capital retributions could be used to punish all those involved or whole communities would have been decimated and made unproductive, but some ringleaders were singled out and executed. Hundred Township Name Occupation or Title Baldslow Crowhurst -

CATSFIELD PARISH COUNCIL the Village Hall, Church Road Catsfield, East Sussex TN33 9DP

The Clerk: Mrs Karen Crowhurst CATSFIELD PARISH COUNCIL The Village Hall, Church Road Catsfield, East Sussex TN33 9DP Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held on Phone 01323 848502 7th November 2018 in Hermon Cottage Email [email protected] Website www.catsfieldpc.co.uk Attended by: Cllr John Overall – Chairman Cllr Thomas- Vice Chairman, Cllr. Edwards, Cllr Hodgson (taking Minutes in the Clerks absence), Cllr Holgate and Cllr Scott. Also in attendance: Cllr Gary Curtis – Rother District Council. Members of the public 1 Item Minutes 1. To receive apologies for absence Apologies were received from County Cllr. Kathryn Field and Karen Crowhurst – The Clerk 2. To approve and accept the minutes of the Parish Council meeting held on 3rd October 2018 RESOLVED: That the Chair of the meeting is authorised to sign the Minutes for 3rd October 2018 3. To receive declarations of interest on agenda items Cllr. Holgate declared a personal interest in: Item 7 – Planning Applications RR/2015/3117/P and RR/2016/162/P for Wylands International Angling Centre, Wylands Farm, Powdermill Lane, Catsfield TN33 0SU, as a neighbour effected by the developments Cllr. Edwards declared a personal interest in: Item 7 – Planning Applications RR/2015/3117/P and RR/2016/162/P for Wylands International Angling Centre, Wylands Farm, Powdermill Lane, Catsfield TN33 0SU, due to family members using the grounds. Cllr. Hodgson declared a personal interest in: Item 6d - Insurance claim – as a relative of the insured. Item 16 – Village Hall as a Trustee and Parish Council’s representative 4. Public questions or comments relating to items on this agenda The Chairman invited the Member of the public to speak. -

World War One: the Deaths of Those Associated with Battle and District

WORLD WAR ONE: THE DEATHS OF THOSE ASSOCIATED WITH BATTLE AND DISTRICT This article cannot be more than a simple series of statements, and sometimes speculations, about each member of the forces listed. The Society would very much appreciate having more information, including photographs, particularly from their families. CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 The western front 3 1914 3 1915 8 1916 15 1917 38 1918 59 Post-Armistice 82 Gallipoli and Greece 83 Mesopotamia and the Middle East 85 India 88 Africa 88 At sea 89 In the air 94 Home or unknown theatre 95 Unknown as to identity and place 100 Sources and methodology 101 Appendix: numbers by month and theatre 102 Index 104 INTRODUCTION This article gives as much relevant information as can be found on each man (and one woman) who died in service in the First World War. To go into detail on the various campaigns that led to the deaths would extend an article into a history of the war, and this is avoided here. Here we attempt to identify and to locate the 407 people who died, who are known to have been associated in some way with Battle and its nearby parishes: Ashburnham, Bodiam, Brede, Brightling, Catsfield, Dallington, Ewhurst, Mountfield, Netherfield, Ninfield, Penhurst, Robertsbridge and Salehurst, Sedlescombe, Westfield and Whatlington. Those who died are listed by date of death within each theatre of war. Due note should be taken of the dates of death particularly in the last ten days of March 1918, where several are notional. Home dates may be based on registration data, which means that the year in 1 question may be earlier than that given. -

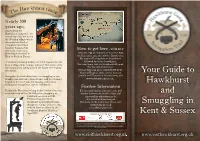

Smugglers Trail Smugglers for Over See Please

www.visithawkhurst.org.uk www.visithawkhurst.org.uk endorsement by HCP. by endorsement inaccuracy can be accepted. Inclusion of any business or organisation does not imply its imply not does organisation or business any of Inclusion accepted. be can inaccuracy ensure accuracy in the production of this information, no liability for any error, omission or omission error, any for liability no information, this of production the in accuracy ensure © 2011 The Hawkhurst Community Partnership ("HCP"). Whilst every effort has been made to made been has effort every Whilst ("HCP"). Partnership Community Hawkhurst The 2011 Supported and funded by funded and Supported Kent & Sussex & Kent April 1747. 1747. April Goudhurst Band of Militia in Militia of Band Goudhurst www.1066country.com reduced after its defeat by the by defeat its after reduced www.visitkent.co.uk though the Gang’s influence was influence Gang’s the though Smuggling in Smuggling For more on the wider area please visit: please area wider the on more For Goudhurst assumed leadership, assumed Goudhurst www.visithawkhurst.org.uk Thomas Kingsmill from Kingsmill Thomas surrounding attractions go to: go attractions surrounding Lydd and executed in 1748. in executed and Lydd further information on the village and village the on information further captured, tried at the Old Bailey for smuggling at smuggling for Bailey Old the at tried captured, and and For accommodation, current events and events current accommodation, For Eventually, Hawkhurst Gang leader Arthur Gray was Gray Arthur leader Gang Hawkhurst Eventually, Further Information Further Hastings to Hawkhurst, Rye to Goudhurst. to Rye Hawkhurst, to Hastings Hawkhurst Islands in the local pubs still running today, from today, running still pubs local the in Islands brandy, rum and coffee from France and the Channel the and France from coffee and rum brandy, www.nationalexpress.com. -

Changes in Rye Bay

CHANGES IN RYE BAY A REPORT OF THE INTERREG II PROJECT TWO BAYS, ONE ENVIRONMENT a shared biodiversity with a common focus THIS PROJECT IS BEING PART-FINANCED BY THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY European Regional Development Fund Dr. Barry Yates Patrick Triplet 2 Watch Cottages SMACOPI Winchelsea DECEMBER 2000 1,place de l’Amiral Courbet East Sussex 80100 Abbeville TN36 4LU Picarde e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Changes in Rye Bay Contents Introduction 2 Location 3 Geography 4 Changes in Sea Level 5 A Timeline of Rye Bay 270 million - 1 million years before present (BP ) 6 450,000-25,000 years BP 6 25,000 – 10,000 years BP 6 10,000 – 5,000 years BP 6 5,000 - 2,000 years BP 7 1st – 5th Century 8 6th – 10th Century 8 11th Century 8 12th Century 8 13th Century 9 14th Century 11 15th Century 12 16th Century 12 17th Century 13 18th Century 15 19th Century 16 20th Century 18 The Future Government Policy 25 Climate Change 26 The Element Of Chance 27 Rye Bay Bibliography 28 Rye Bay Maps 32 2 Introduction This is a report of the Two Bays, One Environment project which encompasses areas in England and France, adjacent to, but separated by the English Channel or La Manche. The Baie de Somme (50 o09'N 1 o27'E) in Picardy, France, lies 90 km to the south east of Rye Bay (50 o56'N 0 o45'E) in East Sussex, England. Previous reports of this project are …… A Preliminary Comparison of the Species of Rye Bay and the Baie de Somme. -

Roads in the Battle District: an Introduction and an Essay On

ROADS IN THE BATTLE DISTRICT: AN INTRODUCTION AND AN ESSAY ON TURNPIKES In historic times travel outside one’s own parish was difficult, and yet people did so, moving from place to place in search of work or after marriage. They did so on foot, on horseback or in vehicles drawn by horses, or by water. In some areas, such as almost all of the Battle district, water transport was unavailable. This remained the position until the coming of the railways, which were developed from about 1800, at first very cautiously and in very few districts and then, after proof that steam traction worked well, at an increasing pace. A railway reached the Battle area at the beginning of 1852. Steam and the horse ruled the road shortly before the First World War, when petrol vehicles began to appear; from then on the story was one of increasing road use. In so far as a road differed from a mere track, the first roads were built by the Roman occupiers after 55 AD. In the first place roads were needed for military purposes, to ensure that Roman dominance was unchallenged (as it sometimes was); commercial traffic naturally used them too. A road connected Beauport with Brede bridge and ran further north and east from there, and there may have been a road from Beauport to Pevensey by way of Boreham Street. A Roman road ran from Ore to Westfield and on to Sedlescombe, going north past Cripps Corner. There must have been more. BEFORE THE TURNPIKE It appears that little was done to improve roads for many centuries after the Romans left. -

Sedlescombe Neighbourhood Plan 2016-2028

SEDLESCOMBE NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2016-2028 Published by Sedlescombe Parish Council under the Neighbourhood Planning (General) Regulations 2012 April 2018 The Vision To make Sedlescombe a vibrant place that values its past but looks to the future, where people are proud to live and work and be part of a caring community. To ensure the character and identity of the village is maintained and enhanced whilst allowing growth and encouraging a sense of community through well planned housing appropriate to the needs of the community. To ensure the natural beauty and key characteristics of this part of the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty are conserved and enhanced. A view of the 13C Parish Church, an older property, an agricultural building and Park Shaw, a 1960’s estate of bungalows The Sedlescombe Neighbourhood Plan was formally ‘made’ by Rother District Council on 23 April 2018 Table of Contents _____________________________________________________________ Foreword 1 Chairman’s Introduction 2 Neighbourhood Planning 4 The Plan Area 4 Period of the Plan 6 Strategic Environmental Assessment 6 The Plan Process 6 How the Neighbourhood Plan was prepared 7 Public Consultation 7 Our Objectives 9 Our Aims 10 Location and Population 10 The Growth of Sedlescombe 11 Sustainable Development 11 The Economic Role 12 The Social Role 12 The Environmental Role 12 The Rother Local Plan 13 The High Weald 14 The Natural and Built Environment 14-15 Climate Change and Flooding 17 Land Use Policies, Introduction 17 Policy 1 Sedlescombe Development Boundary -

PARISH COUNCIL of PLAYDEN, EAST SUSSEX ______Clerk: Lesley Voice, C/O 1 the Grove, Rye, TN31 7ND

PARISH COUNCIL OF PLAYDEN, EAST SUSSEX ____________________________________________________________________ Clerk: Lesley Voice, C/O 1 The Grove, Rye, TN31 7ND. Tel: 07767 221704 Minutes of the Council Meeting held remotely by Zoom and telephone on 3rd December 2020 at 7.30 p.m. Present: Councillors:, Mr P Osborne (PO) Chairman, Mr T Lenihan (TL) Vice Chairman, Mr A. Dickinson (AD), Mr D Stone (DS). East Sussex County Councillor: Not present Rother District Councillor: Not present Members of the Public: 0 Item Action 1 To accept apologies for absence: Sally-Ann Hart (S-A H) (Rother District Council). Now Member of Parliament for Hastings and Rye. Keith Glazier: East Sussex County Councillor 2 Declarations of interest on items on the agenda: AD – Shellfield planning appeal. 3 To approve the minutes of the Parish Council Meeting 5th November 2020: The minutes were unanimously approved and will be signed later by PO. 4 Neighbourhood Watch Report The Clerk had forwarded the Rother monthly newsletter. 5 Reports from visiting Councillors: East Sussex County Councillor: Not present: Rother District Councillor: Not present PO reported that there would be free parking in Rother DC carparks until the end of December on Thursdays and Saturdays. This would not apply to on street parking which is operated locally. Work is being undertaken on the environmental strategy of the Council. The Council continues to work remotely. 6 Public adjournment: To suspend the meeting for any public statements. Members of the public are encouraged to attend the meeting and raise any pertinent issues at this point. No members of the public had joined the Zoom meeting.