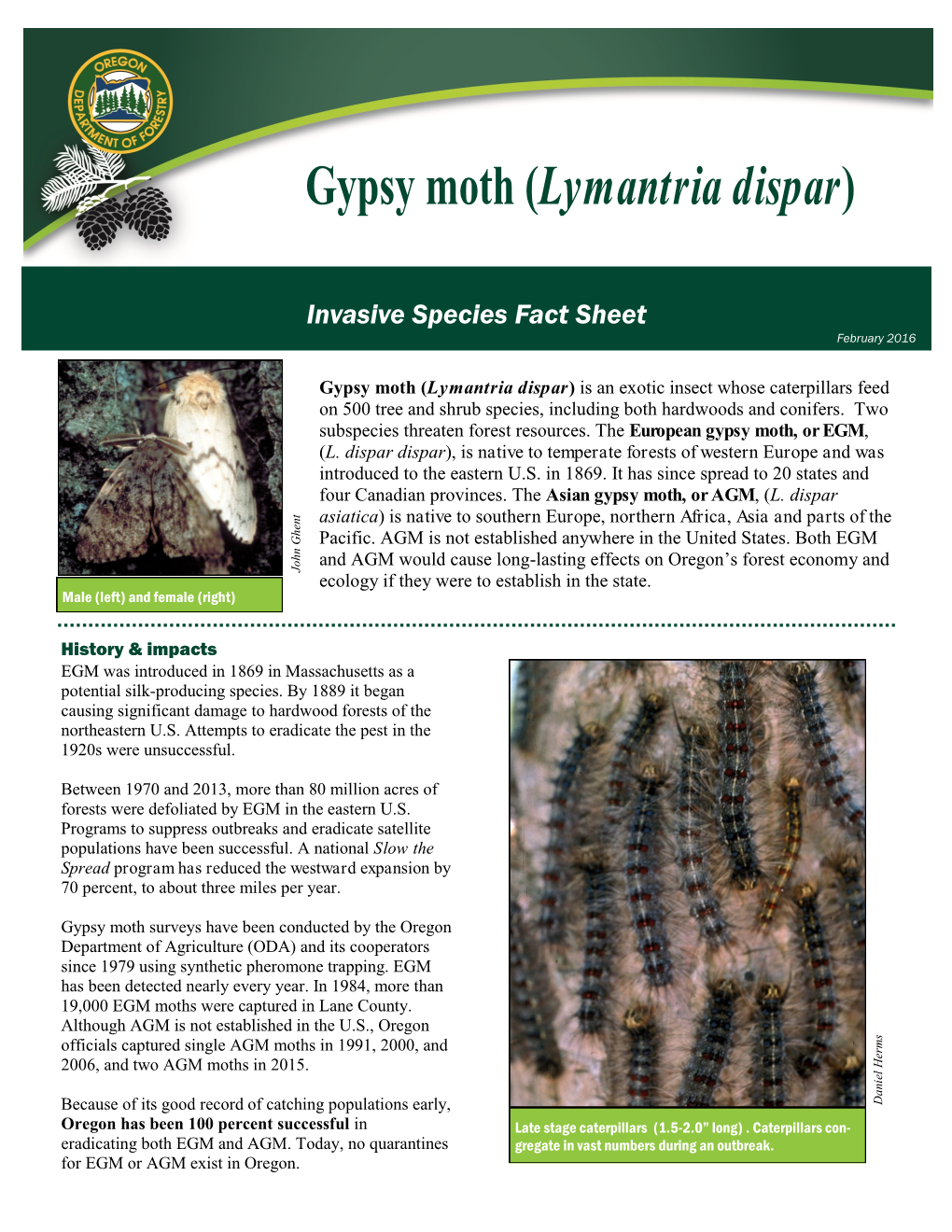

Invasive Species Fact Sheet February 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Composite Insect Trap: an Innovative Combination Trap for Biologically Diverse Sampling

The Composite Insect Trap: An Innovative Combination Trap for Biologically Diverse Sampling Laura Russo1*, Rachel Stehouwer2, Jacob Mason Heberling3, Katriona Shea1 1 Biology Department, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, United States of America, 2 Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States of America, 3 Department of Biology, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, United States of America Abstract Documentation of insect diversity is an important component of the study of biodiversity, community dynamics, and global change. Accurate identification of insects usually requires catching individuals for close inspection. However, because insects are so diverse, most trapping methods are specifically tailored to a particular taxonomic group. For scientists interested in the broadest possible spectrum of insect taxa, whether for long term monitoring of an ecosystem or for a species inventory, the use of several different trapping methods is usually necessary. We describe a novel composite method for capturing a diverse spectrum of insect taxa. The Composite Insect Trap incorporates elements from four different existing trapping methods: the cone trap, malaise trap, pan trap, and flight intercept trap. It is affordable, resistant, easy to assemble and disassemble, and collects a wide variety of insect taxa. Here we describe the design, construction, and effectiveness of the Composite Insect Trap tested during a study of insect diversity. The trap catches a broad array of insects and can eliminate the need to use multiple trap types in biodiversity studies. We propose that the Composite Insect Trap is a useful addition to the trapping methods currently available to ecologists and will be extremely effective for monitoring community level dynamics, biodiversity assessment, and conservation and restoration work. -

Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team

Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER Mating Disruption A REVIEW OF THE USE OF MATING DISRUPTION TO MANAGE GYPSY MOTH, LYMANTRIA DISPAR (L.) KEVIN THORPE, RICHARD REARDON, KSENIA TCHESLAVSKAIA, DONNA LEONARD, AND VICTOR MASTRO FHTET-2006-13 U.S. Department Forest Forest Health Technology September 2006 of Agriculture Service Enterprise Team—Morgantown he Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team (FHTET) was created in 1995 Tby the Deputy Chief for State and Private Forestry, USDA, Forest Service, to develop and deliver technologies to protect and improve the health of American forests. This book was published by FHTET as part of the technology transfer series. http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology/ Cover photos, clockwise from top left: aircraft-mounted pod for dispensing Disrupt II flakes, tethered gypsy moth female, scanning electron micrograph of 3M MEC-GM microcapsule formulation, male gypsy moth, Disrupt II flakes, removing gypsy moth egg mass from modified delta trap mating station. Information about pesticides appears in this publication. Publication of this information does not constitute endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, nor does it imply that all uses discussed have been registered. Use of most pesticides is regulated by State and Federal law. Applicable regulations must be obtained from appropriate regulatory agencies. CAUTION: Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife if not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices given on the label for use and disposal of pesticides and pesticide containers. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for information only and does not constitute an endorsement by the U.S. -

Microsatellite Markers in Hazelnut: Isolation, Characterization, and Cross-Species Amplifi Cation

J. AMER. SOC. HORT. SCI. 130(4):543–549. 2005. Microsatellite Markers in Hazelnut: Isolation, Characterization, and Cross-species Amplifi cation Nahla V. Bassil1 USDA–ARS, NCGR, 33447 Peoria Road, Corvallis, OR 97333 R. Botta Università degli Studi di Torino, Dipartimento di Colture Arboree, Via Leonardo da Vinci 44, 10095 Grugliasco (TO), Italy S.A. Mehlenbacher Oregon State University, Department of Horticulture, 4017 Agricultural and Life Sciences Building, Corvallis, OR 97331 ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. Corylus avellana, simple sequence repeats, SSRs, DNA fi ngerprinting, genetic diversity ABSTRACT. Three microsatellite-enriched libraries of the european hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) were constructed: library A for CA repeats, library B for GA repeats, and library C for GAA repeats. Twenty-fi ve primer pairs amplifi ed easy-to-score single loci and were used to investigate polymorphism among 20 C. avellana genotypes and to evaluate cross-species amplifi cation in seven Corylus L. species. Microsatellite alleles were estimated by fl uorescent capillary electrophoresis fragment sizing. The number of alleles per locus ranged from 2 to 12 (average = 7.16) in C. avellana and from 5 to 22 overall (average = 13.32). With the exception of CAC-B110, di-nucleotide SSRs were characterized by a relatively large number of alleles per locus (≥5), high average observed and expected heterozygosity (Ho and He > 0.6), and a high mean polymorphic information content (PIC ≥ 0.6) in C. avellana. In contrast, tri-nucleotide microsatellites were more homozygous (Ho = 0.4 on average) and less informative than di-nucleotide simple sequence repeats (SSRs) as indicated by a lower mean number of alleles per locus (4.5), He (0.59), and PIC (0.54). -

Empidonax Traillii Extimus) Breeding Habitat and a Simulation of Potential Effects of Tamarisk Leaf Beetles (Diorhabda Spp.), Southwestern United States

A Satellite Model of Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus) Breeding Habitat and a Simulation of Potential Effects of Tamarisk Leaf Beetles (Diorhabda spp.), Southwestern United States Open-File Report 2016–1120 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey A Satellite Model of Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus) Breeding Habitat and a Simulation of Potential Effects of Tamarisk Leaf Beetles (Diorhabda spp.), Southwestern United States By James R. Hatten Open-File Report 2016–1120 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2016 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.http://www.store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Hatten, J.R., 2016, A satellite model of Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus) breeding habitat and a simulation of potential effects of tamarisk leaf beetles (Diorhabda spp.), Southwestern United States: U.S. -

Evaluating Seasonal Variablity As an Aid to Cover-Type Mapping From

PEER.REVIEWED ARIICTE EvaluatingSeasonal Variability as an Aid to Gover-TypeMapping from Landsat Thematic MapperData in the Noftheast JamesR. Schrieverand RussellG. Congalton Abstract rate classifications for the Northeast (Nelson et ol., 1g94i Hopkins ef 01.,19BB). However, despite these advances, spe- Classification of forest cover types in the Northeast is a diffi- cult task. The conplexity and variability in species contposi- cific hardwood forest types have not been reliably classified tion makes various cover types arduous to define and in the Northeast. Developments within the remote sensing identify. This project entployed recent advances in spatial community have shown promise for classification of forest and spectral properties of satellite data, and the speed and cover types throughout the world, These developments indi- potN/er of computers to evaluate seasonol varictbility os an aid cate that, by combining supervised and unsupervised classifi- cation techniques, increases in the accuracy of forest to cover-type mapping from Landsat Thematic Mapper (ru) classifications can be expected (Fleming, 1975; Lyon, 1978; dato in New Hampshire. Dato fron May (bud break), Sep- the su- tember (leaf on), and October (senescence) were used to ex- Chuvieco and Congaiton, 19BBJ.By combining both plore whether different lea.f phenology would improve our pervised and unsupervised processes,a set of spectrally and informationally unique training statistics can be generated. ability to generate forest-cover-type maps. The study area covers three counties in the southeastern corner ol New' This approach resr-rltsin improved classification accuracv (Green Hampshire. A modified supervised/unsupervised approach due to the improved grouping of training statistics was used to classify the cover types. -

Evaluation of Commercial Pheromone Lures and Traps for Monitoring Male Fall Armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in the Coastal Region of Chiapas, Mexico

Malo et al.: Monitoring S. frugiperda with sex pheromone 659 EVALUATION OF COMMERCIAL PHEROMONE LURES AND TRAPS FOR MONITORING MALE FALL ARMYWORM (LEPIDOPTERA: NOCTUIDAE) IN THE COASTAL REGION OF CHIAPAS, MEXICO EDI A. MALO, LEOPOLDO CRUZ-LOPEZ, JAVIER VALLE-MORA, ARMANDO VIRGEN, JOSE A. SANCHEZ AND JULIO C. ROJAS Departamento de Entomología Tropical, El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Apdo. Postal 36, Tapachula, 30700, Chiapas, Mexico ABSTRACT Commercially available sex pheromone lures and traps were evaluated for monitoring male fall armyworm (FAW), Spodoptera frugiperda, in maize fields in the coastal region of Chia- pas, Mexico during 1998-1999. During the first year, Chemtica and Trécé lures performed better than Scentry lures, and there was no difference between Scentry lures and unbaited controls. In regard to trap design, Scentry Heliothis traps were better than bucket traps. In 1999, the pattern of FAW captured was similar to that of 1998, although the number of males captured was lower. The interaction between both factors, traps and lures, was signif- icant in 1999. Bucket traps had the lowest captures regardless of what lure was used. Scen- try Heliothis traps with Chemtica lure captured more males than with other lures or the controls. Delta traps had the greatest captures with Chemtica lure, followed by Trécé and Pherotech lures. Several non-target insects were captured in the FAW pheromone baited traps. The traps captured more non-target insects than FAW males in both years. Baited traps captured more non-target insects than unbaited traps. Key Words: Spodoptera frugiperda, sex pheromone, monitoring, maize, Mexico RESUMEN Se evaluaron feromonas y trampas comercialmente disponibles para el monitoreo del gusano cogollero Spodoptera frugiperda en cultivo de maíz en la costa de Chiapas, México durante 1998-1999. -

Comparison of Pheromone Trap Design and Lures for Spodoptera Frugiperda in Togo and Genetic Characterization of Moths Caught

DOI: 10.1111/eea.12795 Comparison of pheromone trap design and lures for Spodoptera frugiperda in Togo and genetic characterization of moths caught Robert L. Meagher Jr1* ,KomiAgboka2, Agbeko Kodjo Tounou2,DjimaKoffi3,Koffi Aquilas Agbevohia2,Tomfe€ı Richard Amouze2, Kossi Mawuko Adjevi2 &RodneyN. Nagoshi1 1USDA-ARS CMAVE, Insect Behavior and Biocontrol Research Unit, Gainesville, FL 32608, USA , 2Ecole Superieure d’Agronomie, UniversitedeLome, 01 BP 1515, Lome 1, Togo , and 3Africa Regional Postgraduate Programme in Insect Science, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana Accepted: 29 November 2018 Key words: fall armyworm, monitoring, host strain markers, maize, Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, integrated pest management, IPM, rice, Leucania loreyi, COI gene, Tpi gene Abstract Fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), is a pest of grain and vegetable crops endemic to the Western Hemisphere that has recently become widespread in sub- Saharan Africa and has appeared in India. An important tool for monitoring S. frugiperda in the USA is pheromone trapping, which would be of value for use with African populations. Field experiments were conducted in Togo (West Africa) to compare capture of male fall armyworm using three com- mercially available pheromone lures and three trap designs. The objectives were to identify optimum trap 9 lure combinations with respect to sensitivity, specificity, and cost. Almost 400 moths were captured during the experiment. Differences were found in the number of S. frugiperda moths cap- tured in the various trap designs and with the three pheromone lures, and in the number of non-tar- get moths captured with each lure. The merits of each trap 9 lure combination are discussed with respect to use in Africa. -

Biological Infestations Page

Chapter 5: Biological Infestations Page A. Overview ........................................................................................................................... 5:1 What information will I find in this chapter? ....................................................................... 5:1 What is a museum pest? ................................................................................................... 5:1 What conditions support museum pest infestations? ....................................................... 5:2 B. Responding to Infestations ............................................................................................ 5:2 What should I do if I find live pests or signs of pests in or around museum collections? .. 5:2 What should I do after isolating the infested object? ......................................................... 5:3 What should I do after all infested objects have been removed from the collections area? ................................................................................................ 5:5 What treatments can I use to stop an infestation? ............................................................ 5:5 C. Integrated Pest Management (IPM) ................................................................................ 5:8 What is IPM? ..................................................................................................................... 5:9 Why should I use IPM? ..................................................................................................... -

Department of Entomology Newsletter for Alumni and Friends (2009) Iowa State University, Department of Entomology

Department of Entomology Newsletter Entomology 1-2009 Department of Entomology Newsletter For Alumni and Friends (2009) Iowa State University, Department of Entomology Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/entnewsletter Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Iowa State University, Department of Entomology, "Department of Entomology Newsletter For Alumni and Friends (2009)" (2009). Department of Entomology Newsletter. 7. http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/entnewsletter/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Entomology at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Entomology Newsletter by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. January 2009 Newsletter For Alumni and Friends Gassmann Hired as New Corn Entomologist I joined the Department of Entomol- ogy at Iowa State University in Janu- ary 2008. This was not the easiest time of year to leave sunny Tucson, Arizona where I had been working as an Assis- tant Research Scientist in the University of Arizona’s Department of Entomol- ogy. Despite the cold, however, I am delighted to be in Iowa again. I was born and raised in Dubuque County, where my family has deep roots. Vis- its to the farms of relatives and family friends filled much of my early years and gave me a strong affinity toward Iowa agriculture. I am very pleased to have returned to Iowa and am impressed by the wealth of research opportuni- Back row, left to right: Steve Thompson (MS student), Pat Weber ties available in my home state. -

Lymantria Dispar) Populations in the USA

Area-Wide Management of Invading Gypsy Moth (Lymantria dispar) Populations in the USA Andrew Liebhold, USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station, Morgantown, WV USA Numbers of Damaging Non-native Forest Insect & Pathogen species Morgantown, West Virginia Liebhold, A.M., D.G. McCullough, L.M. Blackburn, S.J. Frankel, B. Von Holle and J.E. Aukema. 2013. A highly aggregated geographical distribution of forest pest invasions in the USA. Diversity and Distributions 19, 1208-1216. Alien Forest Insect Establishments in US Over Time All alien forest insects 2.6 species per year 0.5 species per year Economically damaging insect pests Cumulative Pest Establishments Cumulative Year Medford, Massachusetts, 1868 Étienne Léopold Trouvelot, 1827 - 1895 27 Myrtle St., Medford, MA Forbush EH, Fernald CH (1896) The gypsy moth, Porthetria dispar (Linn). Wright and Potter, Boston Eradication is attempted, 1880-1900 “Barrier Zone” The DDT era Application of DDT over Scanton, PA (1948) Gypsy Moth Management Detection / Slow the Eradication Spread Suppression Gypsy Moth Outbreaks Nuisance and aesthetic impacts on homeowners Defoliation Suppression Gypsy Moth Management Detection / Slow the Eradication Spread Suppression Accidental movement of life stages Generally infested Uninfested area area Transition area Gypsy Moth Egg Masses Accidentally Transported During Household Moves Use of pheromone traps to locate and delimit isolated colonies delta trap delimitation base grid grid treatment Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 0 moths/trap >0 moths/trap treatment 350 European -

Impact of Trap Design, Windbreaks, and Weather on Captures of European Corn Borer

Entomology Publications Entomology 12-2006 Impact of Trap Design, Windbreaks, and Weather on Captures of European Corn Borer (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) in Pheromone-Baited Traps Brendon James Reardon Iowa State University Douglas V. Sumerford Iowa State University Thomas W. Sappington Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ent_pubs Part of the Agronomy and Crop Sciences Commons, Atmospheric Sciences Commons, Entomology Commons, and the Systems Biology Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ ent_pubs/226. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Entomology at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Entomology Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Impact of Trap Design, Windbreaks, and Weather on Captures of European Corn Borer (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) in Pheromone-Baited Traps Abstract Pheromone-baited traps are often used in ecological studies of the European corn borer, Ostrinia nubilalis (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). However, differences in trap captures may be confounded by trap design, trap location relative to a windbreak, and changes in local weather. The bjo ectives of this experiment were, first, to examine differences in O. nubilalis adult (moth) captures among the Intercept wing trap, the Intercept bucket/funnel UNI trap, and the Hartstack wire-mesh, 75-cm-diameter cone trap (large metal cone trap) as well as among three cone trap designs. -

Development of the Most Effective Trap to Monitor the Presence of the Cactus Moth Cactoblastis Cactorum (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae)

300 Florida Entomologist 88(3) September 2005 DEVELOPMENT OF THE MOST EFFECTIVE TRAP TO MONITOR THE PRESENCE OF THE CACTUS MOTH CACTOBLASTIS CACTORUM (LEPIDOPTERA: PYRALIDAE) STEPHANIE BLOEM1, STEPHEN D. HIGHT2, JAMES E. CARPENTER3 AND KENNETH A. BLOEM4 1Center for Biological Control, Florida A&M University, Tallahassee, FL 32308 2USDA-ARS-CMAVE at Florida A&M University, Center for Biological Control, Tallahassee, FL 32308 3USDA-ARS-CPMRU, Tifton, GA 31794 4USDA-APHIS-PPQ-CPHST, at Florida A&M University, Center for Biological Control, Tallahassee, FL 32307 ABSTRACT Various trap specifications were evaluated to identify the most effective trap for capturing wild male Cactoblastis cactorum (Berg). All traps were baited with virgin female C. cac- torum and, except for the first comparison of trap type, a standard wing trap was used in all experiments. Although wing traps captured more males than did the other trap types (delta or bucket), the differences were not significant. However, significantly higher numbers of males were captured in wing traps placed 2 m above ground than traps at 1 m or 0.5 m, and wing traps baited with four virgin females caught significantly more males than wing traps baited with a single female. Differences in number of males captured by young and old fe- males were not significant, but more than twice as many males were captured in traps baited with one-day-old females than traps baited with four day old females. In addition, there were no significant differences in number of males caught in unpainted, white, wing traps and wing traps painted one of eight different colors (flat white, black, dark green, flu- orescent green, yellow, fluorescent yellow, orange, or blue), although, more males were cap- tured in the unpainted wing traps.