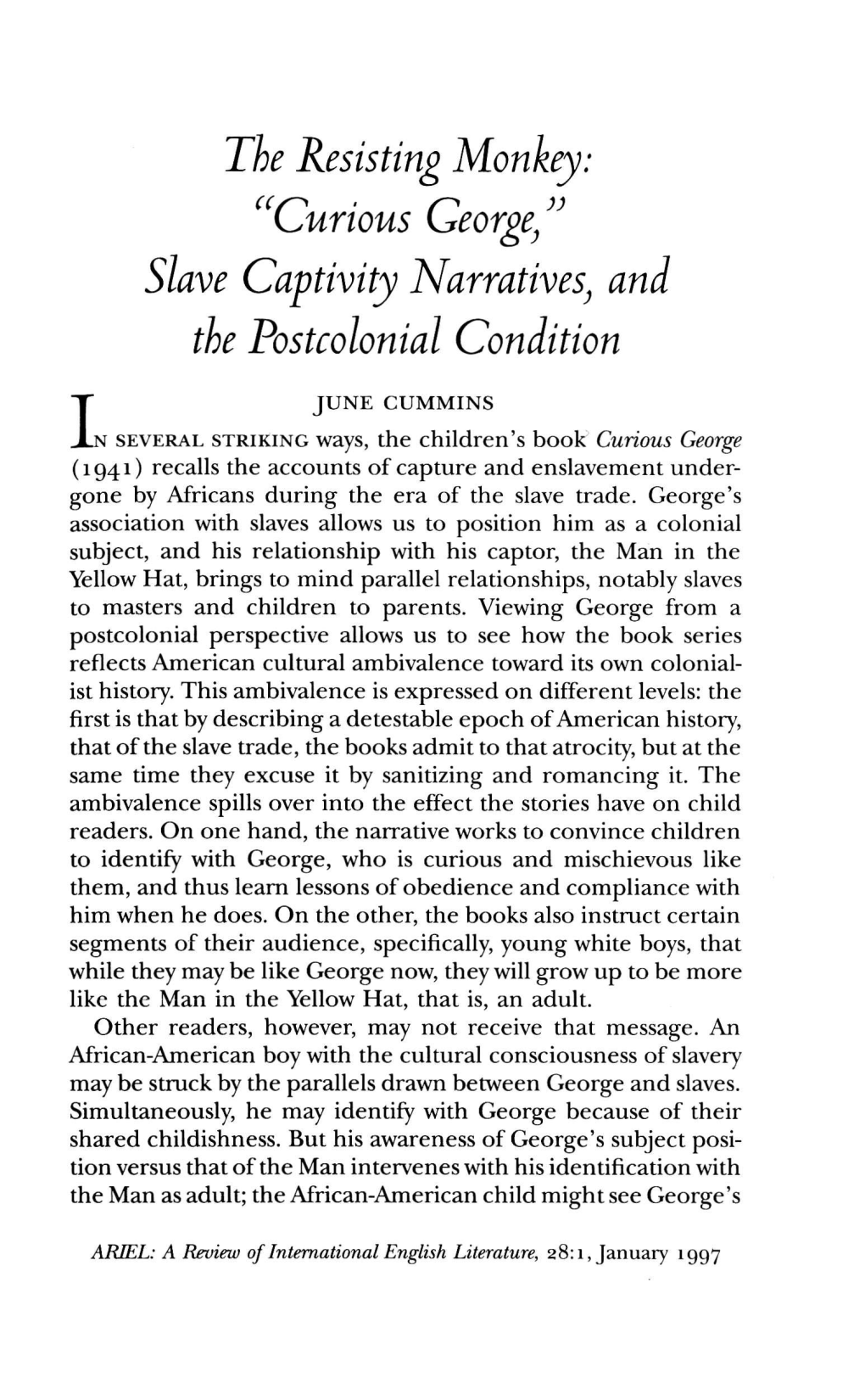

The Resisting Monkey: Furious L,Eorge} Slave Captivity Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curious George and the Pizza by Margret Rey , H.A. Rey , Alan J

Read and Download Ebook Curious George and the Pizza... Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey , H.A. Rey , Alan J. Shalleck (Editor) PDF File: Curious George and the Pizza... 1 Read and Download Ebook Curious George and the Pizza... Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey , H.A. Rey , Alan J. Shalleck (Editor) Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey , H.A. Rey , Alan J. Shalleck (Editor) Curious George is up to his elbows in dough and trouble as he tries his hand at making pizza. Tony the baker chases him out of his restaurant, and George hides in a truck in the alley. An angry Tony becomes a grateful Tony when George helps him deliver a pizza in a way that only a monkey could. Curious George and the Pizza Details Published October 28th 1985 by HMH Books for Young Readers (first published September 30th Date : 1985) ISBN : 9780395390337 Author : Margret Rey , H.A. Rey , Alan J. Shalleck (Editor) Format : Paperback 32 pages Genre : Childrens, Picture Books Download Curious George and the Pizza ...pdf Read Online Curious George and the Pizza ...pdf Download and Read Free Online Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey , H.A. Rey , Alan J. Shalleck (Editor) PDF File: Curious George and the Pizza... 2 Read and Download Ebook Curious George and the Pizza... From Reader Review Curious George and the Pizza for online ebook Cathy says Not the best of the George stories but cute - I just wish people didn't get so mad at George - he's a monkey after all. Jennifer Davis says My 7 year old son recently borrowed this book from his school library. -

Monkey See, Monkey Do: Orientalism in Curious George

Undergraduate Journal of Humanistic Studies Spring 2015 Vol. I • • Monkey See, Monkey Do: Orientalism in Curious George Sam Chao Carleton College November 17, 2014 e tend to approach children’s books as if they were simple or straightforward–as if they had Wonly one moral voice and not a chorus. As Mikhail Bakhtin tells us, “Each word tastes of the context and contexts in which it has lived its socially charged life; all words and forms are populated by intentions” (293). To compress any work into a single, overt or intended “moral” would be a fallacy. Words do not carry fixed meanings; texts do not have fixed interpretations. Bakhtin also points to the “socially charged” nature of words–the “taste of their context and contexts”–calling to mind other critics who have recognized this interface of culture and text. One such critic is Stephen Greenblatt, who says, . if an exploration of a particular culture will lead to a heightened understanding of a work of literature produced within that culture, so too a careful reading of a work of literature will lead to a heightened understanding of the culture within which it was produced. (227) Greenblatt describes how one flavor can be extracted from the “taste” of a text–one context extracted from the layers of contexts–allowing us to examine a culture specific to a time and place. Curious George is a canonized text in American children’s literature: the beloved monkey protagonist of the story has become an icon of childhood. Though read by many, Curious George is not a work approached with scholarly gravity. -

Margret and H. A. Rey and Their Famous Curious George

Margret and H. A. Rey and their famous Curious George by Louise Borden Millions of us around the world have read one or more of the seven original Curious George stories included in this seventy-fifth anniversary edition. My favorites growing up were Curious George Takes a Job and Curious George Rides a Bike. Years after reading those yellow books, I found out what the H and the A stand for in H. A. Rey . and that echoes of H.A.’s life, and those of his wife, Margret, appear in the illustrations of their stories. Maybe you can discover them too. 401 Early Years Hans had one brother and two sisters. From an early age he showed a talent for Hans Augusto Reyersbach was born drawing horses and all kinds in Hamburg, Germany, close to the of things. And he could North Sea. As a boy, he watched mimic the roars of the lions the ships of the world sail into port he saw in the Hagenbeck and unload their cargoes on the Zoo, not far from his house. docks of the river Elbe. H.A. didn’t know then he would grow up to live on three continents . When Hans turned ten on September 16, and be known for creating the most 1908, Margarete Elisabeth Waldstein famous monkey in the world. was only two years old. Her parents lived near the Reyersbachs. Both families were Jewish, and were friends. In 1914, Germany went to war against England, France, and Russia. Sketch by H. A. Rey. 402 403 When Germany lost the war in 1918, Hans went home to Hamburg. -

Monkey See, Monkey Do Children’S Exhibit Coming This Fall to Upper Story Features Curious George of Book, TV Fame

BROWSE FALL 2018 Halloween Plans Blind Manʼs Not Bluffing Apple Caramel Delight There’s Boofest, Uncle Fester’s Closet Among his accomplishments, reading The Cake Lady serves up a dish and spooky stories for adults / Page 4 is important to Jerry Maccoux / Page 5 that captures fall in a bite / Page 12 Monkey See, Monkey Do Children’s exhibit coming this fall to Upper Story features Curious George of book, TV fame he insatiable curiosity of Curious George™ – the Tlittle monkey that has captured the imagination and hearts of children and adults for more than 75 years – comes to life Sept. 21 in the Belt Branch Upper Story. Curious George: Letʼs Get Curious! is a traveling exhibit from the Minnesota Childrenʼs Museum that will bring kids into Georgeʼs world and lead them on an educational adven‐ ture in the libraryʼs largest conference room. Itʼs the second year in a row for Rolling Hills Library to be the host of a traveling exhibit dedicated to children. And be‐ cause of Georgeʼs popularity, the library expects this exhibit to draw even more visitors. “The Amazing Castle™ last year showed us that early liter‐ acy exhibits can make a difference (with attendance) and reach a large number of families,” library Director Michelle Mears said. “We had over 5,000 visits to The Amazing Castle, and weʼre anticipating over 8,000 with Curious George.” Minnesota Childrenʼs Museum also created The Amazing Castle, which was in the Upper Story from Sept. 22, 2017, Please turn to Page 8 Browse a quarterly publication from Monkey Memories Rolling Hills Library that is sponsored by the Friends of Happy reading experiences make a difference, by George Rolling Hills Library e are beyond excited to be hosting the Curious George™: Let’s Get Curious Rolling Hills Library exhibit this fall at Rolling Hills Library. -

As a New Crop of Baby Animals

Expert Guidance on Children’s Interactive Media May 2009 Volume 17, No. 5, Issue 110 Bugsby Reading System Cate West: The Vanishing Files Circus Games Crayola Colorful Journey Curious George’s Dictionary DanceDanceRevolution Disney Grooves Donkey Kong Jungle Beat Elizabeth Find, MD: Diagnosis Mystery Emergency! Disaster Rescue Squad Excitebots: Trick Racing Faceland Free Realms Grand Slam Tennis Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Hell’s Kitchen Intel ClassMate Convertible PC Jewel Master: Cradle of Rome Kids Collection DVDs LEGO Education: WeDo Robotics LEGO Rock Band M&M’s Beach Party Madden NFL 10 Mortimer Beckitt and the Secrets of Spooky Manor NCAA Football 10 Nitro Jr. Notebook Nitro Tunes Desktop PuttingPutting thethe OMG! High School Triple Play Pack Paper Show PebbleGo APTOP PeeWee Pivot Tablet Laptop ““LL”” Penguin Cold Cash Professor Heinz Wolff’s Gravity Ride & Learn Giraffe Bike Rosetta Stone Version 3, Level 1: inin OLPCONE LAPTOP PER CHILD Italian OLPC SCRABBLE The Atom Powered Intel ClassMate Convertable PC Secret Saturdays Sims 3, The Step & Count Kangaroo DDR Disney Grooves, Help for Baby Animals, Curious George on an iPhone, Talking Pens and more.... Super Secret (www.supersecret.com) Tiger Woods PGA Tour 10 TouchMaster 2 Up! V.Smile Smartridges for 2009 One Laptop Per Doctor “Mr. Buckleitner?” My doctor peered into the waiting room, juggling a battered HP Laptop TM in one arm. The computer was clearly both a nuisance and a necessity that had earned a May 2009 proper place in the medical routine. Volume 17, No. 5, Issue 110 As the blood pressure monitor tightened EDITOR Warren Buckleitner, Ph.D., around my arm, I asked about the laptop. -

PBS KIDS, the Number One Educational Media # Brand for Kids, Offers All Children the Opportunity to Explore New Ideas and New Worlds

PBS KIDS, the number one educational media # brand for kids, offers all children the opportunity to explore new ideas and new worlds. 1 Source: Marketing & Research Resources, Inc (M&RR), Jan., 2017 All schedules subject to change without notice. ETV SCHEDULE Committed to making a MONDAY-FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY positive impact on children. Mister Roger’s 6:00 AM ****** Neighborhood Sid The Science Kid In a recent study by Marketing & Research Resources, Inc. (M&RR), PBS KIDS ranked as the 6:30 AM ****** Dinosaur Train Dinosaur Train most educational media brand in comparison 7:00 AM Ready Jet Go! Bob the Builder Sesame Street with six others listed in the study, including 7:30 AM Daniel Tiger’s Daniel Tiger’s Universal Kids, Disney Channel, Disney Junior, Cat in the Hat Neighborhood Neighborhood Nick Jr., Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network. 1 8:00 AM Pinkalicious & ETVW SCHEDULE Nature Cat ****** Peterrific Why Sponsor? 8:30 AM Curious George ****** Splash and Bubbles SUNDAY Pinkalicious & As America’s largest classroom, PBS KIDS offers 9:00 AM Peterrific ****** Curious George 8:00 AM BizKid$ a variety of kid and parent approved shows that 9:30 AM Daniel Tiger’s Nature Cat 8:30 AM Kid Stew/SciGirls target important learning objectives for develop- Neighborhood ****** 10:00 AM Daniel Tiger’s ing minds with the unmatched benefit of a non- Neighborhood ****** Ready Jet Go! commercial environment. SCETV is viewed as a 10:30 AM Splash and Bubbles treasured community resource and a provider of high quality, educational content. Aligning your 11:00 AM Sesame Street brand with the undisputed leader in children’s programming gives you access to an engaged 11:30 AM Super Why! audience. -

First Ever Curious George® Holiday Special a Very Monkey Christmas Premieres November 25Th on Pbs Kids®

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MONKEY AROUND THE CHRISTMAS TREE THIS HOLIDAY SEASON! FIRST EVER CURIOUS GEORGE® HOLIDAY SPECIAL A VERY MONKEY CHRISTMAS PREMIERES NOVEMBER 25TH ON PBS KIDS® Boston, MA and Universal City, CA, October 27, 2009—Go on a holiday adventure with Curious George as he prepares for Christmas Day in A Very Monkey Christmas—the charming new holiday special from PBS KIDS’ CURIOUS GEORGE making its broadcast premiere on public television stations nationwide Wednesday, November 25 (check local listings). A Very Monkey Christmas marks George’s first foray into the world of holiday-themed programming, and is bound to become a holiday tradition for kids from one to 92! Peppered with classic Christmas carols, A Very Monkey Christmas also features three original songs —“Are You Ready?”, “Something As Special as You”, and “Christmas Monkey.” “Viewers of all ages will fall in love with A Very Monkey Christmas,” said Executive Producer for WGBH Dorothea Gillim. “The special features some of the series’ most beloved characters in a story that reveals the true spirit of the holiday season, and highlights the importance of spending time with those you love all year long.” A Very Monkey Christmas finds George and The Man with the Yellow Hat preparing for Christmas, when they encounter a dilemma—neither can figure out what to give the other for a present! The Man finds George’s wish list filled with geometric shapes, and George doesn’t have a clue what to get The Man who has everything. The Man suggests that George surprise him with a homemade gift, but George isn’t quite sure what a monkey can make for a man. -

Margret and HA Rey's Curious George and the Puppies

A Fish Out of Water Helen Marion Palmer Random House (1961) Summary: Illus. in color. "Comic pictures show how the fish rapidly outgrows its bowl, a vase, a cook pot, a bathtub."--The New York Times. Genre: Juvenile Fiction Number of Pages: 64 Language: English ISBN: 9780394900230 Reading Status: Unread Date Added: May 11, 2021 Tags: English Picture Books Notes: English Children Box 24 A Fishy Story Gail Donovan Night Sky Books (2001) Summary: Puffer has seen and done everything, and tells the most amazing stories, but when a new fish named Angel arrives, Puffer gets caught in a lie. Will anyone ever believe Puffer again? Genre: Fishes Number of Pages: 24 Language: English ISBN: 9781590140284 Reading Status: Unread Date Added: May 11, 2021 Tags: English Picture Books Notes: English Children Box 24 All about Corduroy Don Freeman Viking Press (1978) Summary: Corduroy: A toy bear in a department store wants a number of things, but when a little girl finally buys him he finds what he has always wanted most of all ; A pocket for Corduroy: A toy bear who wants a pocket for himself searches for one in a laundromat. Number of Pages: 60 Language: English ISBN: 9780681889217 Reading Status: Unread Date Added: May 11, 2021 Tags: English Picture Books Notes: English Children Box 24 All are welcome Alexandra Penfold Alfred A. Knopf (2018) Genre: Schools Number of Pages: 34 ISBN: 9780525579649 Reading Status: Unread Category: English Picture Books Date Added: January 28, 2021 Tags: English Picture Books Notes: Picture Books Children German Box #4 And Kangaroo Played His Didgeridoo Nigel Gray Scholastic Press (2005) Summary: You should have come to this Great Aussie Do, the guest list sure read like an Aussie Who's Who. -

『Playing with Curious George』

Thursday, May 10th, 2018 Opening Date for New Interactive Attraction featuring the Lovable & Globally Popular* Curious George! Let's be George! Curious George Breaks Out of Cartoon World 『Playing With Curious George 』 Opening Saturday, June 30th, 2018! Let your curiosity take over and go on an adventure with the curious little monkey, George! Universal Studios Japan is proud to announce that the park will open a new show, “Playing With Curious George”, before summer vacation begins on Saturday, June 30th, 2018. The new show is based on the “Curious George” children’s book character, globally popular for over 75 years. Children will love playing with the curious little monkey and letting their curiosity take over in this new interactive attraction that is fun for the whole family. *Accolades: The book series has been translated into 26 languages worldwide, with total sales exceeding 80 million copies. One of the volumes deemed a masterpiece of children's literature by the New York Public Library. Telegraph’s 100 Best Children’s Books of All Time Publisher’s Weekly All-Time Bestselling Children’s Books The Curious George TV Show series received two Daytime Emmy Awards in the United States (2008 and 2010). 【About Playing With Curious George】 ★Attraction Story★ Watch the animator, the artist behind the beloved Curious George cartoons, as he creates the Curious George cartoon in the animation studio and witness a world of surprises along the way. Feel the excitement as Curious George breaks out of the cartoon world and into the real one! This is your chance to become friends with George! The new attraction combines production technology and props with animation to create one immersive environment. -

{Download PDF} Curious George Super Sticker Activity Book

CURIOUS GEORGE SUPER STICKER ACTIVITY BOOK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK H A Rey | 124 pages | 21 Oct 2009 | HOUGHTON MIFFLIN | 9780547238968 | English | Boston, United States Curious George Super Sticker Activity Book PDF Book Sign Up. For example, we use cookies to conduct research and diagnostics to improve our content, products and services, and to measure and analyse the performance of our services. Curious George Storybook Collection H. Product details For ages Format Paperback pages Dimensions x x Show less Show more Advertising ON OFF We use cookies to serve you certain types of ads , including ads relevant to your interests on Book Depository and to work with approved third parties in the process of delivering ad content, including ads relevant to your interests, to measure the effectiveness of their ads, and to perform services on behalf of Book Depository. Margret and H. Report incorrect product information. After the Reys escaped Paris by bicycle in carrying the manuscript for the original Curious George , the book was published in America in About H. But it was their rambunctious little monkey who became an instantly recognizable icon. Cancel Save settings. We use cookies to provide our services , for example, to keep track of items stored in your shopping basket, prevent fraudulent activity, improve the security of our services, keep track of your specific preferences e. Are you happy to accept all cookies? Non permanent markers work better then crayons but that may be our preference. Walmart July 25, Verified purchase. Sometimes straight up sticker books should 'stick' to what they know-- stickers. Coronavirus delivery updates. -

Evaluation of Curious George

Concord Evaluation Group Evaluation of Curious George MAY 2012 Contact: Christine Paulsen, Ph.D. [email protected] PO Box 694 | Concord, MA 01742 | concordevaluation.com Table of Contents Background ......................................................................................................... 1 Methods and Procedures .................................................................................... 2 Study Design ................................................................................................... 2 Hypotheses and Research Questions ............................................................. 5 Survey Instruments ......................................................................................... 7 Participants ......................................................................................................... 9 Findings .............................................................................................................13 Reading Curious George books boosted young children’s science and math knowledge. .....................................................................................................13 Curious George books prompted children to use scientific habits of mind while reading. ..........................................................................................................15 Watching Curious George episodes also boosted young children’s science and math knowledge. ............................................................................................16 -

Celebrating the Life of Ed Lakin

Jewish Federation of Reading/Berks Non-Profit Organization Jewish Cultural Center, PO Box 14925 U.S. Postage PAID Reading, PA 19612-4925 Permit No. 2 readingjewishcommunity.org Reading, PA Change Service Requested Enriching Lives Volume 47, No. 9 September 2017 Elul 5777-Tishri 5778 Shalom0918 ShaloThe Journal of the Reading Jewish Communitym published by0 the Jewish9 Federation1 of Reading/Berks7 Your Federation Supports: Jewish Education Celebrating the life Food Pantry of Ed Lakin Friendship Circle Ed Lakin was known to many as the more quiet, less flamboyant half of Chevra the partnership that turned Boscov’s Department Stores into a regional retail Community Shabbat powerhouse. But to the Jewish community and the other important causes he supported so generously, he was regarded as a giant. The names of Ed Reading Jewish Film Series and his late second wife, Alma, grace great institutions such as our Jewish community preschool and the Holocaust Resource Center and Library at PJ Library theCenterPAlbright College.iec Their philanthropy hase had a tremendous0 impact9 in so 18 Jewish Family Service many other ways. Ed Lakin passed away in August at the age of 94. His memory will be a blessing for his community for generations to come. Jewish Cultural Center Look inside this edition of Shalom for four pages of memories from the Lakin Holocaust Library family members, friends and associates who knew and loved him. & Resource Center Israel & Overseas Ruth Messinger to speak here Oct. 4 Camp Scholarships On Thursday, Oct. 4, at 5:30 p.m., you A minimum Community Campaign Israel Trips are invited to attend Jewish Federation of gift of $1,200 per person is requested to Reading/Berks’ 2019 Jewish Community attend the dinner.