Mergers Simulation and Demand Analysis for the U.S. Carbonated Soft Drink Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keurig to Acquire Dr Pepper Snapple for $18.7Bn in Cash

Find our latest analyses and trade ideas on bsic.it Coffee and Soda: Keurig to acquire Dr Pepper Snapple for $18.7bn in cash Dr Pepper Snapple Group (NYSE:DPS) – market cap as of 17/02/2018: $28.78bn Introduction On January 29, 2018, Keurig Green Mountain, the coffee group owned by JAB Holding, announced the acquisition of soda maker Dr Pepper Snapple Group. Under the terms of the reverse takeover, Keurig will pay $103.75 per share in a special cash dividend to Dr Pepper shareholders, who will also retain 13 percent of the combined company. The deal will pay $18.7bn in cash to shareholders in total and create a massive beverage distribution network in the U.S. About Dr Pepper Snapple Group Incorporated in 2007 and headquartered in Plano (Texas), Dr Pepper Snapple Group, Inc. manufactures and distributes non-alcoholic beverages in the United States, Mexico and the Caribbean, and Canada. The company operates through three segments: Beverage Concentrates, Packaged Beverages, and Latin America Beverages. It offers flavored carbonated soft drinks (CSDs) and non-carbonated beverages (NCBs), including ready-to-drink teas, juices, juice drinks, mineral and coconut water, and mixers, as well as manufactures and sells Mott's apple sauces. The company sells its flavored CSD products primarily under the Dr Pepper, Canada Dry, Peñafiel, Squirt, 7UP, Crush, A&W, Sunkist soda, Schweppes, RC Cola, Big Red, Vernors, Venom, IBC, Diet Rite, and Sun Drop; and NCB products primarily under the Snapple, Hawaiian Punch, Mott's, FIJI, Clamato, Bai, Yoo- Hoo, Deja Blue, ReaLemon, AriZona tea, Vita Coco, BODYARMOR, Mr & Mrs T mixers, Nantucket Nectars, Garden Cocktail, Mistic, and Rose's brand names. -

Online Appendix: Not for Publication the Competitive Impact of Vertical Integration by Multiproduct Firms

Online Appendix: Not For Publication The Competitive Impact of Vertical Integration by Multiproduct Firms Fernando Luco and Guillermo Marshall A Model Consider a market with NU upstream firms, NB bottlers, and a retailer. There are J inputs produced by the NU upstream firms and J final products produced by the NB bottlers. Each final product makes use of one (and only one) input product. All J final products are sold by the retailer. The set of products produced by each upstream i j firm i and bottler j are given by JU and JB, respectively. In what follows, we restrict j j to the case in which the sets in both fJBgj2NB and fJU gj2NU are disjoint (i.e., Diet Dr Pepper cannot be produced by two separate bottlers or upstream firms). We allow for a bottler to transact with multiple upstream firms (e.g., a PepsiCo bottler selling products based on PepsiCo and Dr Pepper SG concentrates). The model assumes that linear prices are used along the vertical chain. That is, linear prices are used both by upstream firms selling their inputs to bottlers and by bottlers selling their final products to the retailer. The price of input product j set by an upstream firm is given by cj; the price of final good k set by a bottler is wk; and the retail price of product j is pj. We assume that the input cost of upstream firms is zero, and the marginal costs of all other firms equals their input prices. The market share of product j, given a vector of retail prices p, is given by sj(p). -

Product Differentiation and Mergers in the Carbonated Soft Drink Industry

Product Differentiation and Mergers in the Carbonated Soft Drink Industry JEAN-PIERRE DUBE´ University of Chicago Graduate School of Business Chicago, IL 60637 [email protected] I simulate the competitive impact of several soft drink mergers from the 1980s on equilibrium prices and quantities. An unusual feature of soft drink demand is that, at the individual purchase level, households regularly select a variety of soft drink products. Specifically, on a given trip households may select multiple soft drink products and multiple units of each. A concern is that using a standard discrete choice model that assumes single unit purchases may understate the price elasticity of demand. Tomodel the sophisticated choice behavior generating this multiple discreteness,Iuse a household-level scanner data set. Market demand is then computed by aggregating the household estimates. Combining the aggregate demand estimates with a model of static oligopoly, I then run the merger simulations. Despite moderate price increases, I find substantial welfare losses from the proposed merger between Coca-Cola and Dr. Pepper. I also find large price increases and corresponding welfare losses from the proposed merger between Pepsi and 7 UP and, more notably, between Coca-Cola and Pepsi. 1. Introduction With the advent of aggregate brand-level data collected at supermarket checkout scanners, researchers have begun to use structural econo- metric models for policy analysis. The rich content of scanner data enables the estimation of demand systems and their corresponding cross-price elasticities. The areas of merger and antitrust policy have been strong beneficiaries of these improved data. Recent advances in structural approaches to empirical merger analysis consist of combining Iamvery grateful to my thesis committee: David Besanko, Tim Conley, Sachin Gupta, and Rob Porter. -

Carbonated Soft Drinks in the US Through 2025

Carbonated Soft Drinks in the U.S. through 2025: Market Essentials 2021 Edition (To be published September 2021. Data through 2020. Market projections through 2025.) More than 120 Excel tables plus an executive summary detailing trends and comprehensive profiles of leading companies, their brands and their strategies. his comprehensive market research report on the number-two T beverage category examines trends and top companies' For A Full strategies. It provides up-to-date statistics on leading brands, Catalog of packaging, quarterly growth and channels of distribution. It also Reports and offers data on regional markets, pricing, demographics, Databases, advertising, five-year growth projections and more. Go To The report presents the data in Excel spreadsheets, which it supplements with a concise executive summary highlighting key bmcreports.com developments including the impact of the coronavirus pandemic as well as a detailed discussion of the leading carbonated soft drink (CSD) companies. INSIDE: REPORT OVERVIEW A brief discussion of key AVAILABLE FORMAT & features of this report. 2 PRICING TABLE OF CONTENTS Direct Download A detailed outline of this Excel sheets, PDF, PowerPoint & Word report’s contents and data tables. 7 $4,395 To learn more, to place an advance order or to inquire about SAMPLE TEXT AND additional user licenses call: Charlene Harvey +1 212.688.7640 INFOGRAPHICS ext. 1962 [email protected] A few examples of this report’s text, data content layout and style. 13 HAVE Contact Charlene Harvey: 212-688-7640 x 1962 QUESTIONS? [email protected] Beverage Marketing Corporation 850 Third Avenue, 13th Floor, New York, NY 10022 Tel: 212-688-7640 Fax: 212-826-1255 The answers you need Carbonated Soft Drinks in the U.S. -

Strategic Analysis of the Coca-Cola Company

STRATEGIC ANALYSIS OF THE COCA-COLA COMPANY Dinesh Puravankara B Sc (Dairy Technology) Gujarat Agricultural UniversityJ 991 M Sc (Dairy Chemistry) Gujarat Agricultural University, 1994 PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION In the Faculty of Business Administration Executive MBA O Dinesh Puravankara 2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2007 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author APPROVAL Name: Dinesh Puravankara Degree: Master of Business Administration Title of Project: Strategic Analysis of The Coca-Cola Company. Supervisory Committee: Mark Wexler Senior Supervisor Professor Neil R. Abramson Supervisor Associate Professor Date Approved: SIMON FRASER UNIVEliSITY LIBRARY Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "lnstitutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: ~http:llir.lib.sfu.calhandle/l8921112>)and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

2017 Plains Region Portfolio 2017 Plains Region Portfolio Norfolk Division 2001 Riverside Blvd

2017 Plains Region Portfolio 2017 Plains Region Portfolio Norfolk Division 2001 Riverside Blvd. Norfolk, NE 68701 (402) 371-9347 or (866) 248-7645 Fax: (866) 592-3774 Mick Lusero Omaha Branch Manager [email protected] (402) 505-2634 Jonathan Grimm Brian Buresh Distribution Supervisor Warehouse Supervisor [email protected] [email protected] (402) 860-1472 (402) 860-0757 Rick Anderson Jennifer Risinger Vending Department Administrative Assistant [email protected] [email protected] (402) 616-5777 (402) 371-9347 Danny Olson Sales – Yankton/Wayne – Northern Region [email protected] (402) 649-6681 Scott Weinrich Sales – Norfolk/West Point – Central Region [email protected] (402) 750-5365 Randy Walnofer Sales – Columbus/Schuyler – Southern Region [email protected] (402) 992-9101 TO PLACE AN ORDER For equipment service: [email protected] [email protected] (800) 862-1904, option #2 (866) 592-3774, option #2 Please include your account number and business name Carbonated Soft Drinks 12oz Cans (2x12pk) Dr Pepper Dr Pepper TEN Diet Dr Pepper 1000 0836 Deposit 1000 1754 Deposit 1000 3730 1000 2434 No Deposit 1000 2435 No Deposit 0-78000-08216-6 0-78000-10316-8 0-78000-08316-3 Cherry Diet Cherry Dr Pepper Dr Pepper 1000 1749 1000 1750 0-78000-09816-7 0-78000-09916-4 Dr Pepper Diet Caffeine Free Made with Sugar Dr Pepper 1000 2778 1000 0835 0-78000-10216-1 0-78000-08516-7 Carbonated Soft Drinks 12oz Cans (2x12pk) 7Up 7Up TEN Diet 7Up 1000 0829 Deposit 1000 0830 Deposit 1002 0900 -

DR PEPPER SNAPPLE GROUP ANNUAL REPORT DPS at a Glance

DR PEPPER SNAPPLE GROUP ANNUAL REPORT DPS at a Glance NORTH AMERICA’S LEADING FLAVORED BEVERAGE COMPANY More than 50 brands of juices, teas and carbonated soft drinks with a heritage of more than 200 years NINE OF OUR 12 LEADING BRANDS ARE NO. 1 IN THEIR FLAVOR CATEGORIES Named Company of the Year in 2010 by Beverage World magazine CEO LARRY D. YOUNG NAMED 2010 BEVERAGE EXECUTIVE OF THE YEAR BY BEVERAGE INDUSTRY MAGAZINE OUR VISION: Be the Best Beverage Business in the Americas STOCK PRICE PERFORMANCE PRIMARY SOURCES & USES OF CASH VS. S&P 500 TWO-YEAR CUMULATIVE TOTAL ’09–’10 JAN ’10 MAR JUN SEP DEC ’10 $3.4B $3.3B 40% DPS Pepsi/Coke 30% Share Repurchases S&P Licensing Agreements 20% Dividends Net Repayment 10% of Credit Facility Operations & Notes 0% Capital Spending -10% SOURCES USES 2010 FINANCIAL SNAPSHOT (MILLIONS, EXCEPT EARNINGS PER SHARE) CONTENTS 2010 $5,636 NET SALES +2% 2009 $5,531 $ 1, 3 21 SEGMENT +1% Letter to Stockholders 1 OPERATING PROFIT $ 1, 310 Build Our Brands 4 $2.40 DILUTED EARNINGS +22% PER SHARE* $1.97 Grow Per Caps 7 Rapid Continuous Improvement 10 *2010 diluted earnings per share (EPS) excludes a loss on early extinguishment of debt and certain tax-related items, which totaled Innovation Spotlight 23 cents per share. 2009 diluted EPS excludes a net gain on certain 12 distribution agreement changes and tax-related items, which totaled 20 cents per share. See page 13 for a detailed reconciliation of the Stockholder Information 12 7 excluded items and the rationale for the exclusion. -

COCA-COLA 1 the Coca-Cola Company Nick White Lourdes

Running Head: COCA-COLA 1 The Coca-Cola Company Nick White Lourdes University COCA-COLA 2 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………….………………………...3 Domains …………………………………………………………...…………….………......5 Management …………………………………………………………....…………...5 Legal Environment ………………………………………………………………….8 Economic Environment …………………………………………………………….11 International Business ……………………………………………………………...14 Summary …………………………………………………………………………………...17 References ………………………………………………………………………………….18 COCA-COLA 3 The Coca-Cola Company Introduction Beginning in 1886, pharmacist Dr. John S. Pemberton created a distinctive flavored syrup that, when mixed with carbonated water, became what most people know today as “Coca-Cola.” Fast forward to today, The Coca-Cola Company is currently the world’s largest, non-alcoholic beverage producer, bringing in over $31 billion in net operating revenues in 2018 (Coca-Cola History, 2019). Besides being the largest producer of soft drinks, Coca-Cola has a few other strengths. First, Coca-Cola has a solid brand identity, meaning its logo and name are well known around the world in over 200 countries. Moreover, the company is known for producing not only its main product, but it is well known to produce a wide variety of non-alcoholic beverages. Coca-Cola also has a high retention of its customer base because, while there are alternatives to Coca-Cola, there is no other alternative that tastes exactly the same as a traditional Coca-Cola. Besides having and acknowledging strengths, The Coca-Cola Company does have its weaknesses. While the company excels in producing beverages across all of its product lines, that is the only type of product it produces. This is a drawback for Coca-Cola, as it limits the company's potential growth and leaves a way for competitors, like PepsiCo (sometimes referred to as Pepsi) who owns the Lay’s Potato Chip company, to expand into different markets. -

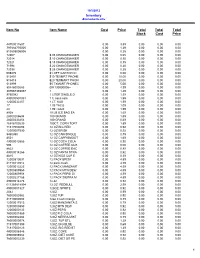

TX Convenient Database

10/5/2012 Inventory Alphabetically Item No Item Name Cost Price Total Total Total Stock Cost Price 44700011607 0.00 3.89 0.00 0.00 0.00 797884770005 0.00 1.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 813805005008 0.00 0.25 0.00 0.00 0.00 72007 $.05 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.05 0.00 0.00 0.00 72014 $.10 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.10 0.00 0.00 0.00 72021 $.15 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.15 0.00 0.00 0.00 71994 $.20 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.20 0.00 0.00 0.00 72038 $.25 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.25 0.00 0.00 0.00 609470 $1 OFF CARTON CI 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 513401 $10 TEXMRT PHONE 0.00 10.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 513418 $20 TEXMART PHON 0.00 20.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 513999 $5 TXMART PHONEC 0.00 5.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 90446000283 004130000006+ 0.00 4.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 307667393057 1 0.00 1.49 0.00 0.00 0.00 9750982 1 LITER SINGLE D 0.00 1.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 490000501031 1 lt. coca cola 0.00 1.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 12000032257 1 LT. KAS 0.00 1.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 17 1.09 TACO 0.00 1.09 0.00 0.00 0.00 24 1.99 TACO 0.00 1.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 8938 10 LB ICE BAG EA 0.00 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 28000206604 100 GRAND 0.00 1.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 28000333454 100 GRAND 0.00 0.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 16916100239 100CT. -

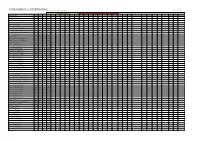

Allergen Information | All Soft Drinks & Minerals

ALLERGEN INFORMATION | ALL SOFT DRINKS & MINERALS **THIS INFORMATION HAS BEEN RECORDED AND LISTED ON SUPPLIER ADVICE** DAYLA WILL ACCEPT NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR INACCURATE INFORMATION RECEIVED Cereals containing GLUTEN Nuts Product Description Type Pack ABV % Size Wheat Rye Barley Oats Spelt Kamut Almonds Hazelnut Walnut Cashews Pecan Brazil Pistaccio Macadamia Egg Crustacean Lupin Sulphites >10ppm Celery Peanuts Milk Fish Soya Beans Mollusc Mustard Sesame Seeds Appletiser 24x275ml Case Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Cox's Apple Sprkl 12x275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Cranberry&Orange Sprkl 12x275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG E'flower CorDial 6x500ml Minerals Case 0 500ml BG E'flower Sprkl 12x275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Ginger&Lemongrass Sprkl 12x275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Ginger&Lemongrass Sprkl SW 12X275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Pomegranate&E'flower Sprkl 12X275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Strawberry CorDial 6x500ml Minerals Case 0 500ml Big Tom Rich & Spicy Minerals Case 0 250ml √ Bottlegreen Cox's Apple Presse 275ml NRB Minerals Case 0 275ml Bottlegreen ElDerflower Presse 275ml NRB Minerals Case 0 275ml Britvic 100 Apple 24x250ml Case Minerals Case 0 250ml Britvic 100 Orange 24x250ml Case Minerals Case 0 250ml Britvic 55 Apple 24x275ml Case Minerals Case 0 275ml Britvic 55 Orange 24x275ml Case Minerals Case 0 275ml Britvic Bitter Lemon 24x125ml Case Minerals Case 0 125ml Britvic Blackcurrant CorDial 12x1l Case Minerals Case 0 1l Britvic Cranberry Juice 24x160ml Case Minerals Case 0 160ml Britvic Ginger Ale 24x125ml Case Minerals Case -

Exhibit Sales

Exhibit Sales are OPEN! Exhibit at InterBev for access to: • Beverage producers and distributors • Owners and CEOs • Sales/marketing professionals • Packaging and process engineers • Production, distribution and warehousing managers • R&D personnel Specialty Pavilions: • New Beverage Pavilion • Green Pavilion • Organic/Natural Pavilion NEW FOR 2012! “Where the beverage industry does business.” October 16-18, 2012 Owned & Operated by: Sands Expo & Convention Center Las Vegas, Nevada, USA Supported by: www.InterBev.com To learn more, email [email protected] or call 770.618.5884 Soft Drinks Internationa l – July 2012 ConTEnTS 1 news Europe 4 Africa 6 Middle East 8 India 10 The leading English language magazine published in Europe, devoted exclusively to the manufacture, distribution and marketing of soft drinks, fruit juices and bottled water. Asia Pacific 12 Americas 14 Ingredients 16 features Acerola, Baobab And Juices & Juice Drinks 18 Ginseng 28 Waters & Water Plus Drinks 20 Extracts from these plants offer beverage manufacturers the opportunity to enrich Carbonates 22 products in many ways, claims Oliver Sports & Energy 24 Hehn. Adult/Teas 26 Re-design 30 Packaging designed to ‘leave an impres - Packaging sion’ has contributed to impressive 38 growth, according to bottlegreen. Environment 40 People Closure Encounters 30 42 Rather than placing a generic screw top Events 43 onto a container at the very end of the design process, manufacturers need to begin with the closure, writes Peter McGeough. Adding Value To Bottled Water 34 From Silent Salesman 32 In the future, most volume growth in bot - Steve Osborne explores the marketing tled water will come from developing opportunities presented by multi-media markets, so past dynamics are likely to regulars technologies and how these might be continue. -

BRITVIC Annual Report 2014 V1.Indb

annual report 2014 making life’s everyday moments more enjoyable Welcome to Britvic’s 2014 Annual Report for the financial year ended 28 September 2014. In this report you can read about our business and what we do, find information on our strategy and how we deliver it, how we have performed in the financial year and how we govern our business. 01 Strategic report 01 Performance at a glance 03 Chairman’s introduction 04 Our business 06 Our business model 07 Our strategy 07 Risk management 08 Our people 12 Chief Executive Officer’s review 15 Chief Financial Officer’s review 20 Glossary 22 Our sustainability performance 28 Our risks 02 Governance 33 Corporate governance report 34 Board of directors 43 Audit Committee 46 Nomination Committee 50 Remuneration Committee 51 Directors’ remuneration report 63 Annual report on remuneration 74 Directors’ report 76 Statement of directors’ responsibilities 03 Financial statements 78 Independent auditors report to the members of Britvic plc 81 Consolidated income statement 82 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income/(expense) 83 Consolidated balance sheet 84 Consolidated statement of cash flows 85 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 86 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 135 Company balance sheet 136 Notes to the company financial statements 04 Other information 143 Shareholder information Cautionary note regarding forward-looking statements This announcement includes statements that are forward-looking in nature. Forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors which may cause the actual results, performance or achievements of the group to be materially different from any future results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements.