4. Alpine and Meadow Ecosystems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GEOLOGIC MAP of the Mccoy PEAK QUADRANGLE, SOUTHERN CASCADE RANGE, WASHINGTON

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Geologic map of the McCoy Peak quadrangle, southern Cascade Range, Washington by Donald A. Swanson1 Open-File Report 92-336 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. 'U.S. Geological Survey, Department of Geological Sciences AJ-20, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................ 1 5. Locations of samples collected in McCoy Peak ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................... 1 {quadrangle ......................... 6 ROCK TERMINOLOGY AND CHEMICAL 6. Alkali-lime classification diagram for Tertiary CLASSIFICATION .................... 2 rocks in McCoy Peak quadrangle .......... 7 GENERAL GEOLOGY .................... 6 7. Plot of FeO*/MgO vs. SiO2 for rocks from TERTIARY ROCKS OLDER THAN INTRUSIVE McCoy Peak quadrangle ................ 7 SUITE OF KIDD CREEK ............... 7 8. Plot of total alkalis vs. SiO2 for rocks in McCoy Volcaniclastic rocks ................... 7 Peak quadrangle ..................... 8 Chaotic volcanic breccia ................ 8 9. Plot of K2O vs. SiO2 for rocks from McCoy Vitroclastic dacite and andesite breccia ...... 9 Peak quadrangle ..................... 8 Volcanic centers ...................... 10 10. Distrbution of pyroxene andesite and basaltic Regional dike swarm .................. 11 andesite dikes in French Butte, Greenhorn Age .............................. 13 Buttes, Tower Rock, and McCoy Peak INTRUSIVE SUITE OF KIDD CREEK ......... 13 quadrangles ........................ 12 Dikes ............................. 14 11. Rose diagrams of strikes of dikes and beds in Sills .............................. 16 McCoy Peak and other quadrangles ....... 13 Relation of dikes and sills ............... 16 12. Plcts of TiO2, FeO*, and MnO vs. -

Roadless Rule and Dark Divide the Dark Divide Was Once Much Larger Than Its Current 76,000 Acres

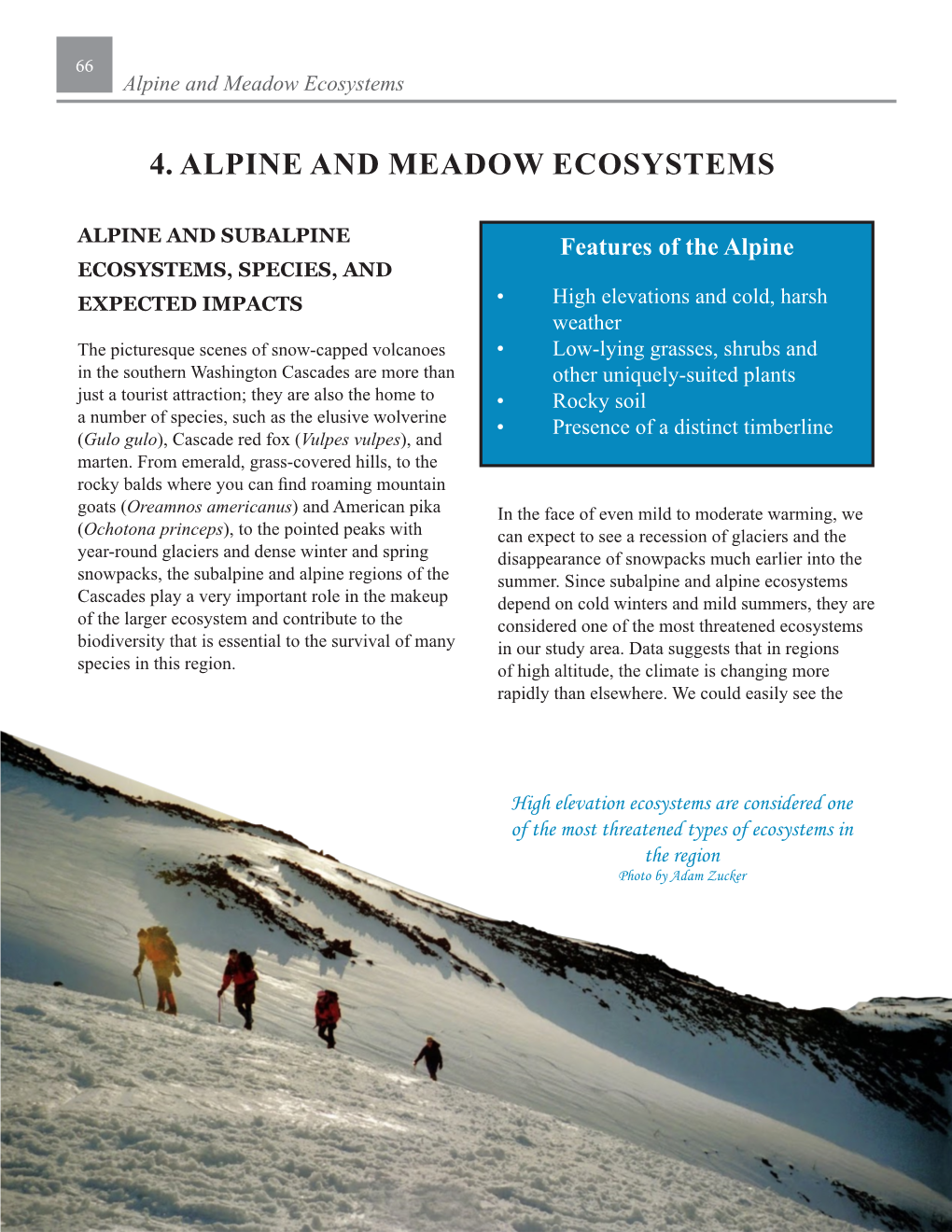

Exploring the PRING S RA Dark Divide I Despite its intimidating name, the Dark Divide is a place of sunny ridges and tremendous wildflower meadows. The region is endangered, however, by threats from off-road vehicle use. Southwest Washington’s threatened gem By Andrew Engelson soils and meadows. The region was A thick layer of ash from the 1980 excluded from the protections of the eruption of Mount St. Helens is still Don’t be afraid of the Dark Divide. 1984 Washington Wilderness Bill. prominent. Even with a somewhat ominous But hikers are slowly reclaiming the The region is home to a variety of name, this spectacular roadless area ridges with their boots. And there are forest ecosystems, all dependent on between Mount St. Helens and Mt. many reasons to go: unique geology, wildfires. Huge wildfires in the early Adams is actually filled with light: sun- abundant wildflowers and wildlife, 1900s left many of the open meadows baked ridges, subalpine forests, and and superb views. and silver-gray snags you’ll find there meadows exploding with wildflowers. The lava flows that are the founda- today. Even so, the region is home to Named for the 19th century miner tion of the 76,000-acre region are huge trees. Just outside the Dark and settler John Dark, the Dark approximately 20 to 25 million years Divide roadless area, you can find the Divide long served as hunting and old. Areas such as Juniper and world’s largest noble fir, near gathering grounds for American Langille Ridge were actually once Yellowjacket Creek. -

Gifford Pinchot

THE FORGOTTEN FOREST: EXPLORING THE GIFFORD PINCHOT A Publication of the Washington Trails Association1 7A 9 4 8 3 1 10 7C 2 6 5 7B Cover Photo by Ira Spring 2 Table of Contents About Washington Trails Association Page 4 A Million Acres of outdoor Recreation Page 5 Before You Hit the Trail Page 6 Leave No Trace 101 Page 7 The Outings (see map on facing page) 1. Climbing Mount Adams Pages 8-9 2. Cross Country Skiing: Oldman Pass Pages 10-11 3. Horseback Riding: Quartz Creek Pages 12-13 4. Hiking: Juniper Ridge Pages 14-15 5. Backpacking the Pacific Crest Trail: Indian Heaven Wilderness Pages 16-17 6. Mountain Biking: Siouxon Trail Pages 18-19 7. Wildlife Observation: Pages 20-21 A. Goat Rocks Wilderness B. Trapper Creek Wilderness C. Lone Butte Wildlife Emphasis Area 8. Camping at Takhlakh Lake Pages 22-23 9. Fly Fishing the Cowlitz River Pages 24-25 10. Berry Picking in the Sawtooth Berry Fields Pages 26-27 Acknowledgements Page 28 How to Join WTA Page 29-30 Volunteer Trail Maintenance Page 31 Important Contacts Page 32 3 About Washington Trails Association Washington Trails Association (WTA) is the voice for hikers in Washington state. We advocate protection of hiking trails, take volunteers out to maintain them, and promote hiking as a healthy, fun way to explore Washington. Ira Spring and Louise Marshall co-founded WTA in 1966 as a response to the lack of a political voice for Washington’s hiking community. WTA is now the largest state-based hiker advocacy organization in the country, with over 5,500 members and more than 1,800 volunteers. -

Summary of Public Comment, Appendix B

Summary of Public Comment on Roadless Area Conservation Appendix B Requests for Inclusion or Exemption of Specific Areas Table B-1. Requested Inclusions Under the Proposed Rulemaking. Region 1 Northern NATIONAL FOREST OR AREA STATE GRASSLAND The state of Idaho Multiple ID (Individual, Boise, ID - #6033.10200) Roadless areas in Idaho Multiple ID (Individual, Olga, WA - #16638.10110) Inventoried and uninventoried roadless areas (including those Multiple ID, MT encompassed in the Northern Rockies Ecosystem Protection Act) (Individual, Bemidji, MN - #7964.64351) Roadless areas in Montana Multiple MT (Individual, Olga, WA - #16638.10110) Pioneer Scenic Byway in southwest Montana Beaverhead MT (Individual, Butte, MT - #50515.64351) West Big Hole area Beaverhead MT (Individual, Minneapolis, MN - #2892.83000) Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, along the Selway River, and the Beaverhead-Deerlodge, MT Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness, at Johnson lake, the Pioneer Bitterroot Mountains in the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest and the Great Bear Wilderness (Individual, Missoula, MT - #16940.90200) CLEARWATER NATIONAL FOREST: NORTH FORK Bighorn, Clearwater, Idaho ID, MT, COUNTRY- Panhandle, Lolo WY MALLARD-LARKINS--1300 (also on the Idaho Panhandle National Forest)….encompasses most of the high country between the St. Joe and North Fork Clearwater Rivers….a low elevation section of the North Fork Clearwater….Logging sales (Lower Salmon and Dworshak Blowdown) …a potential wild and scenic river section of the North Fork... THE GREAT BURN--1301 (or Hoodoo also on the Lolo National Forest) … harbors the incomparable Kelly Creek and includes its confluence with Cayuse Creek. This area forms a major headwaters for the North Fork of the Clearwater. …Fish Lake… the Jap, Siam, Goose and Shell Creek drainages WEITAS CREEK--1306 (Bighorn-Weitas)…Weitas Creek…North Fork Clearwater. -

Cascade Forest Conservancy 2020 Annual Report

Cascade Forest Conservancy 2020 Annual Report Three months and ten days into our 35th year as an organization, the Board of Directors and I decided to ask our staff to work from home. At the time, we all hoped to come back to the office within a month. Two months seemed like a worst-case scenario. As I write this, we are still working remotely. At the beginning of 2020, none of us anticipated how different and how tough the year would be. Yet Cascade Forest Conservancy showed remarkable resilience at every level of our organization. Our staff continued to fight to protect and restore the southern Washington Cascades. Our Board continued to provide direction and leadership. And our community of volunteers, supporters, and donors showed up, again and again, to keep Cascade Forest Conservancy strong. Despite many challenges, we moved forward undeterred. We continued to fight to protect places like the Pumice Plain and the Green River Valley from harmful projects and mining. We expanded some ongoing restoration programs, like beaver reintroduction, and launched new ground-breaking projects like the Instream Wood Bank Network (instreamwoodbanknetwork.com). And we hosted successful online events to build community and support our work at a distance, such as our annual auction and screenings of documentaries and films like The Dark Divide. Many volunteer trips were reimagined to keep volunteers and staff safe from COVID-19. Our 2020 volunteers put on masks, stood far apart, and came out to donate their time and energy to important conservation and restoration initiatives that wouldn’t have been possible without their help. -

Washington Trails Jul+Aug 2011

Trail Work Myth-Busting, p.12 Maps You Need, p.33 Trappers Peak, p.51 WASHINGTON TRAILS July + August 2011 » A Publication of Washington Trails Association www.wta.org » $4.50 Head to the Crest Hike the Pacific Crest Trail for stellar views and soul repair INSIDE PCT Feats and Firsts Trail Angels Trail Magic Plus, How to Tell Better Tales Make Fish Tacos in the Backcountry This Month’s Cover » Photo by Karl Forsgaard Hiker Greg Jacoby amidst lupines and » Table of Contents bistort on the Pacific Crest Trail near White Pass July+August 2011 Volume 47, Issue 4 News + Views Backcountry The Front Desk » Craig McKibben The Gear Closet » Susan Ashlock, Why we need the PCT, even if we never Adam Scroggins hike it.» p.4 Navigate to the right map.» p.33 Family-friendly camping gear.» p.35 The Signpost » Lace Thornberg What motivates a PCT thru-hiker?» p.5 Sage Advice » Chris Wall How to tell spell-binding tales.» p.38 Trail Talk » Reader survey results and a Q&A session Trail Eats » Sarah Kirkconnell Dinner for two trailside.» with search and rescue.» p.6 p.40 Hiking News » 12Susan Elderkin Anniversaries and road closures.» p.8 Take a Hike WTA at Work Day Hikes and Overnights » Suggested hikes statewide.» p.41 Trail Work » Diane Bedell We take a pulaski to our favorite trail main- Nature on Trail » Sylvia Feder tenance myths.» p.12 22 You’ve seen krummholz before, but did you know what it was?» Action for Trails » Jonathan Guzzo, p.49 Ryan Ojerio A legislative session look back.» p.16 A Walk on the Wild Side » Why the Dark Divide goes too often unex- Elizabeth Lunney plored.» p.17 The essence of trail magic.» p.50 Membership News » Kara Chin Featured Landscape » Buff Black Hike-a-Thon—it’s on!» p.20 Why you really must visit Trappers Peak.» Heidi Walker p.51 On Trail Special Feature » All about the Pacific Crest Trail Best bets for a day or weekend.» p.22 PCT personalities.» 24 p.25 The PCT across a lifetime.» p.28 The PCT’s bold trendsetters.» p.31 Volunteer Vacations on the crest.» p.32 Find WTA online at www.wta.org. -

The Dark Divide Have You Been There Lately—Or Ever? This Area Offers All the Charms of Its Well-Known Neighbors, but It’S Often Overlooked

July + August 2011 » Washington Trails WTA at Work « 17 The Dark Divide Have you been there lately—or ever? This area offers all the charms of its well-known neighbors, but it’s often overlooked Make it to the top of Snagtooth Mountain in Forest Service had not considered the environ- The Quartz Creek the Dark Divide Roadless Area and you’ll be mental impacts that such motorized recreation Trail features rewarded with the largest clearcut free vista would impose on the landscape. tremendous old remaining in the South Cascades. To the east, Of the area’s 18 major trails, only the Quartz growth. Photo by you’ll peer into the Quartz Creek valley, home Creek Trail is designated nonmotorized. In the Kurt Wieland. to towering old-growth trees. To the north, Quartz Creek Valley, where motorcycles are the spine of the Dark Divide is punctuated with craggy peaks. Ridgetop meadows ex- tend west and east separating the Cispus and the Lewis River drainages. At more than 75,000 acres, the Dark Divide is the largest roadless area in West- ern Washington, yet relatively few hikers venture there. Either they haven’t heard of it at all, or what they have heard of the Dark Divide—that its trails are motorized and unmaintained—keeps them away. The Dark Divide’s neighbors all have impressive titles: Mount Rainier National Park, Mount St. Helens National Monu- ment and the Columbia River Gorge Na- tional Scenic Area. The Goat Rocks, Indian Heaven and Mount Adams are designated wilderness areas, garnering more hiker attention. -

Gifford Pinchot National Forest Land Management Plan

GPNF Land and Resource Management Plan, 1990 00_Preface.doc,1 Land and Resource Management Plan Final Environmental Impact Statement Gifford Pinchot National Forest Preface This Forest Land and Resource Management Plan (Forest Plan) has been prepared according to Secretary of Agriculture regulations (36 CFR 219) which are based on the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act (RPA) as amended by the National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA). The Plan has also been developed in accordance with regulations (40 CFR 1500) for implementing the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA). Because this Plan is considered a major federal action significantly affecting the quality of the human environment, a detailed statement (environmental impact statement) has been prepared as required by NEPA. The Forest Plan represents the implementation of the Preferred Alternative as identified in the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) for the Forest Plan. If any particular provision of this Forest Plan, or the application thereof to any person or circumstances, is found to be invalid, the remainder of the Forest Plan and the application of that provision to other persons or circumstances shall not be affected. Additional information about this Plan is available from: Forest Supervisor Gifford Pinchot National Forest PO Box 8944 6926 E. Fourth Plain Blvd. Vancouver, WA 98668-8944 (206) 696-7500 GPNF Land and Resource Management Plan 01_Introduction.doc, 1 Chapter I Forest Plan Introduction Purpose of the Forest Plan The Forest Plan guides all natural resource management activities and establishes management Standards/Guidelines for the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. It describes resource management practices, levels of resource production and management, and the availability and suitability of lands for resource management. -

P4-Apr 01 IJW V7

INTERNATIONAL Journal of Wilderness APRIL 2001 VOLUME 7, NUMBER 1 FEATURES EDUCATION AND COMMUNICATION 3 EDITORIAL PERSPECTIVES 30 The BLM in Partnership with the Student The Wildness of Rivers Conservation Association: Restoring BY ALAN WATSON Wilderness in the California Desert BY DAVE WASH and KATIE WASH 4 SOUL OF THE WILDERNESS The World Wilderness Congress SCIENCE AND RESEARCH BY VANCE G. MARTIN 31 Economic Values of the U.S. Wilderness System: Research Evidence to Date and STEWARDSHIP Questions for the Future 10 Bob Marshall 1901-1939 BY JOHN B. LOOMIS and ROBERT RICHARDSON Wilderness Preservationist BY CHAD P. DAWSON 35 Controlling Nature: Is Science to Blame? BY NAOMI ORESKES and REBECCA ORESKES 12 The New Forest Service Wilderness Recreation Strategy 39 Whitewater Boaters in Utah Personal Viewpoints from Diverse Interests Implications for Wild River Planning BY DALE J. BLAHNA and DOUGLAS K. REITER INTRODUCTION BY JOHN HENDEE, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF 12 Balancing Freedom and Protection in 44 PERSPECTIVES FROM THE ALDO LEOPOLD Wilderness Recreation Use WILDERNESS RESEARCH INSTITUTE BY DAVID COLE Wilderness Fire BY DAVID J. PARSONS 13 A New Wilderness Recreation Strategy for National Forest Wilderness WILDERNESS DIGEST BY GARRY OYE 45 Announcements and 15 The New Forest Service Wilderness Recreation Wilderness Calendar Strategy Spells Doom for the National Wilderness Preservation System 47 Book Reviews BY BILL WORF The Trade Off Myth: Fact and Fiction About Jobs 17 If We Lock People Out, Who Will Fight to and the Environment Save Wilderness? by Eban Goodstein • REVIEWED BY JOHN SHULTIS Mighty River: A Portrait of the Fraser BY IRA SPRING by Richard C. -

Opportunities for Wild & Scenic River Designation In

OPPORTUNITIES FOR WILD & SCENIC RIVER DESIGNATION IN SOUTHWEST WASHINGTON’S “VOLCANO COUNTRY” Washington's legendary volcanoes - Mount St. Helens, Mount Rainier and Mount Adams - are the source of wild, free-flowing rivers and streams that rush through deep gorges and basalt canyons on their way to the Columbia. Rivers like the Cispus, Green, and Lewis are well-known for their outstanding recreational, fisheries, wildlife, historical, and scientific values. Major portions of the most unique and wild rivers in Volcano Country have no permanent protection from new hydropower, water storage dams, or other harmful projects. Protecting the wild rivers of Southwest Washington's Volcano Country under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act - the strongest protection we can give to rivers Mount Rainer and Mount Adams are sources of - would permanently safeguard this region's unique and wild, free-flowing rivers treasured natural heritage. In Oregon, 60 of the state's (Joel Mann, www.flickr.com) most exceptional rivers are protected as Wild and Scenic. Yet in Washington, only six rivers have this status. In 1990, the U. S. Forest Service evaluated over a dozen BENEFITS OF DESIGNATION rivers in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest and found • Protects the river's free-flowing character, them eligible for inclusion in the national Wild and Scenic water quality and outstanding values Rivers system. Now, a diverse array of interested citizens and organizations are teaming up to build the widespread public • Promotes river-friendly land use practices support necessary to pass legislation designating these • Protects important fish and wildlife habitat outstanding rivers as Wild and Scenic - thereby keeping them • Protects existing, compatible uses of the intact for fish, wildlife, and future generations. -

WTU Herbarium Specimen Label Data

WTU Herbarium Specimen Label Data Generated from the WTU Herbarium Database September 27, 2021 at 11:56 am http://biology.burke.washington.edu/herbarium/collections/search.php Specimen records: 1329 Images: 108 Search Parameters: Label Query: Genus = "Arnica" Asteraceae Asteraceae Arnica mollis Hook. Arnica sachalinensis (Regel) A. Gray U.S.A., WASHINGTON, SKAGIT COUNTY: RUSSIAN FEDERATION, SAKHALIN REGION: North Cascades National Park; Boston Basin, 2 miles northwest of Sakhalin Island; on west side of island along Hwy 495 4 km SSW of Cascade Pass. Lesogorsk and just north of Tel'novskiy, at mouth of unnamed Elev. 5800 ft. stream emptying into Tatary Straight. 48° 30' 2.04439" N, 121° 3' 57.54291" W; UTM Zone 10, Elev. 10 ft. 642869E, 5373526N; Source: Calc. from UTM, UTM from field Shrubby gully opening to beach, with Alnus, Salix, Petasites, notes. Senecio, grasses. Rays yellow; common on open slopes. Subalpine meadows; rocky soil; with Valeriana sitchensis, Veratrum Phenology: Flowers. Origin: Native. viride, Carex spp., Vaccinium spp. Ray flowers yellow; uncommon. Phenology: Flowers. Origin: Native. Ben Legler 843 23 Jul 2003 Gerald Schneeweiss 30 10 Aug 2002 Herbarium: WTU with Hanna Weiss, Ben Legler Herbarium: NOCA, NPS accession 632, catalog 23372 Asteraceae Asteraceae Arnica cordifolia Hook. Arnica ovata Greene U.S.A., OREGON, WALLOWA COUNTY: Wallowa-Whitman National Forest. Lick Creek Campground, north of U.S.A., WASHINGTON, SKAGIT COUNTY: campground, south of USFS guard station. North Cascades National Park. Fisher Creek Basin. In avalanche Elev. 5409 ft. chute west of Fisher Creek camp, on north side of Fisher Creek. 45° 9.702' N, 117° 2.119' W Elev. -

Geologic Map of the East Canyon Ridge Quadrangle, Southern Cascade Range, Washington

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Geologic map of the East Canyon Ridge quadrangle, southern Cascade Range, Washington by Donald A. Swanson1 Open-File Report 94-591 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. 'U.S. Geological Survey, Department of Geological Sciences AJ-20, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................. 1 FIGURES ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ....................... 1 1. Map showing location of East Canyon Ridge ROCK TERMINOLOGY AND CHEMICAL quadrangle relative to other quadrangles and the CLASSIFICATION .......................... 2 Southern Washington Cascades Conductor .... 2 GEOLOGIC OVERVIEW OF QUADRANGLE ...... 7 2. Map of East Canyon Ridge quadrangle, showing TERTIARY ROCKS OLDER THAN INTRUSIVE localities mentioned in text ................. 3 SUTTEOFKIDDCREEK..................... 8 3. Total alkali-silica classification diagram for rocks in Volcaniclastic rocks (map unit Ttv) ............. 8 East Canyon Ridge quadrangle .............. 3 Lava flows and domes ........................ 9 4. Plot of phenocryst assemblage vs. SiO2 for rocks in Intrusions ................................. 10 East Canyon Ridge quadrangle .............. 6 Dikes .................................. 10 5. Locations of samples collected in East Canyon Ridge Plugs and other intrusions ................. 10 quadrangle ............................. 6 Silicic intrusions ......................... 11 6. Alkali-lime classification diagram for Tertiary RHYOLITE INTRUSION OF SPUD HILL ........ 12 rocks in East Canyon Ridge quadrangle ....... 6 OTHER SILICIC INTRUSIONS ............... 12 7. Plot of FeO*/MgO vs. SiO2 for rocks in East Can INTRUSIVE SUITE OF KIDD CREEK ........... 13 yon Ridge quadrangle ....................