Paul Brunton: a Bridge Between India and the West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Appeal of Ramana Maharsi in the West

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 14 Article 10 January 2001 The Sage of Pure Experience: The Appeal of Ramana Maharsi in the West Thomas A. Forsthoefel Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Forsthoefel, Thomas A. (2001) "The Sage of Pure Experience: The Appeal of Ramana Maharsi in the West," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 14, Article 10. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1253 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Forsthoefel: The Sage of Pure Experience: The Appeal of Ramana Maharsi in the West The Sage of Pure Experience: The Appeal of Ramana Maharsi in the Westl Professor Thomas A. Forsthoefel Mercyhurst College WILHELM Halbfass's seminal study of appeal among thinkers and spiritUal adepts the concept of experience in Indian religions in the West. Indeed, such 'meeting at the illuminates the philosophical ambiguities of heart' in interfaith dialogue promises the term and its recent appropriations by communion even in the face of unresolved some neo-Advaitins. to serve apologetic theoretical dilemmas. 2 ends. Anantanand Rambachand's own The life and work of Ramana (1879- study of the process of liberation in Advaita 1950), though understudied, are important Vedanta also critically reviews these for a number of reasons, not the least of apologetic strategies, arguing that in which is the fact that together they represent privileging anubhava, they undervalue or a version of Advaita abstracted from misrepresent the im;ortance given to sruti in traditional monastic structures, thus Sankara's Advaita. -

Nirodbaran Talks with Sri Aurobindo 01

Talks with Sri Aurobindo Volume 1 by Nirodbaran Sri Aurobindo Ashram Pondicherry NOTE These talks are from my notebooks. For several years I used to record most of the conversations which Sri Aurobindo had with us, his attendants, and a few others, after the accident to his right leg in November 1938. Besides myself, the regular participants were: Purani, Champaklal, Satyendra, Mulshankar and Dr. Becharlal. Occasional visitors were Dr. Manilal, Dr. Rao and Dr. Savoor. As these notes were not seen by Sri Aurobindo himself, the responsibil- ity for the Master's words rests entirely with me. I do not vouch for absolute accuracy, but I have tried my best to reproduce them faithfully. I have made the same attempt for the remarks of the others. NIRODBARAN i PREFACE The eve of the November Darshan, 1938. The Ashram humming with the ar- rival of visitors. On every face signs of joy, in every look calm expectation and happiness. Everybody has retired early, lights have gone out: great occa- sion demands greater silent preparation. The Ashram is bathed in an atmos- phere of serene repose. Only one light keeps on burning in the corner room like a midnight vigil. Sri Aurobindo at work as usual. A sudden noise! A rush and hurry of feet breaking the calm sleep. 2:00 a.m. Then an urgent call to Sri Aurobindo's room. There, lying on the floor with his right knee flexed, is he, clad in white dhoti, upper body bare, the Golden Purusha. The Mother, dressed in a sari, is sitting beside him. -

Helena Roerich

HELENA ROERICH In the difficult days of world upheavals, of human disunity, of the neglecting of all the higher principles of Being, which are the only true givers of life and which lead to the evolu- tion of the world, there must be heard a voice calling for the resurrection of the spirit and for the bringing of the fire of achievement into all the actions of life. And, of course, this voice must be the voice of woman, who during mil- lenniums has drunk the chalice of suffering and humiliation and has forged her spirit in the greatest patience. Helena Roerich elena Roerich (1879–1955) was a prominent Russian thinker, enthusiast and writer whose H artistic heritage represents a very distinctive phenomenon in Russian and global scientific and philo- sophical thought. The principal work of her life – the books on the Living Ethics, dedicated to the issues of the cosmic evolution of the mankind, and her episto- lary work, closely related to her books, laid a firm foun- dation for many cultural and spiritual movements that were developing in the 20th century. Helena was born on the 12th of February 1879 in Saint Petersburg, in the family of Ivan Shaposhnikov, an architect who taught at the Institute of Civil Engineers, and his wife Yekaterina (née Golenischeva-Kutuzova), grand-niece of the great Russian field marshall Kutuzov. Since early childhood, Helena displayed remarkable abilities. By the age of six she could read and write in three languages. In adolescence she took serious in- terest in literature and philosophy. In 1895 she gradu- ated from the Mariinsky Gymnasium with honors and Nicholas Roerich. -

4006 05.Patil Mahesh

Aayushi International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (AIIRJ) PEER REVIEW IMPACT FACTOR ISSN VOL- VI ISSUE-IX SEPTEMBER 2019 e-JOURNAL 5.707 2349-638x A Siddhantic Interpretation On ‘Bhutebhyo Hi Param Tasmaat Naasti Chinta Chikitsite’ Patil Mahesh Annasaheb Professor , Sant Gajanan Ayurveda Medical college , Mahagaon Abstract – Ayurvedic scholars are well aware that sarvadravyam panchbhoutikam asminarhte1ie..All the matters are derived from panchmahabhoot and similarly all the bodies are also made up of panchmahabhoot ( panchmahabhoot shari`r is amvaayiiti sharir ) In Ayurveda different definitions for the sharir had been told as Ekdhatwatmak , dwidhatwatmak , ashtadhatwatmak , chaturvimshatitatwatmaketc but the physiological definition is ‘dosh dhatu mala mulam hi shariram2ⁱ‘ and these Dosh , Dhatu ,Malas are the derivatives of panchmahabhoot(sloka ..) thus clearing that panchmahabhoot forms the foundation for formation of body.But whenever the issue of health and disease occurs the classics had defined it on the state of dosh dahtu level as Samdoshsamagnisamdhatu …and Rogastu doshvaishyamyam3. If we see keenly the origin of panchmahabhoot they have been derived from panchtanmatrasie subtle mahabhootas which in turn are are derivatives of preceding elements as Rajas and Tamas and so on till Avyakt. Whenever we speak about health and diseases relative to Dosh , Dhatu ,Malassamyavastha and vishamavastha indirectly it is concerned to the panchmahabhootas status only. Further if we probe into panchmahabhootas we can reach to rajas tamas -

Complete List Catalog

Cultivate an open mind Complete List Catalog www.questbooks.net 2012 House Publishing Theosophical TABLECOMPLETE OF CONTENTS QUEST TITLE LIST QUEST BOOKS are published by THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN AMERICA P.O. Box 270, Wheaton, Illinois 60187-0270. The Society is a branch of a world fellowship and membership organization dedicated to promoting the unity of humanity and encouraging the study of Complete Quest Title List ............................................................ 3 religion, philosophy, and science so that we may better understand ourselves and our relationships within Complete Adyar Title List ...........................................................13 this multidimensional universe. The Society stands for complete freedom of individual search and belief. Complete Study Guide List .......................................................21 For further information about its activities, write to the above address, call CD / Audio Program List.............................................................21 1-800-669-1571, e-mail [email protected], or consult its Web page: www.theosophical.org. DVD / Video Program List ..........................................................28 Author Index ..................................................................................36 VISIT OUR WEBSITE AT Order Forms....................................................................................46 WWW.QUESTBOOKS.NET Visit our website for interactive features now available Ordering Information....................................Inside -

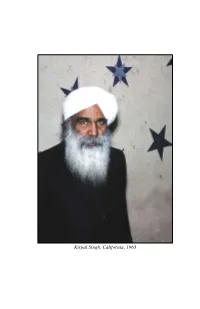

Kirpal-Singh-The-Jap-Ji.Pdf

INTRODUCTION Kirpal Singh, California, 1963 THE JAP JI INTRODUCTION THE JAP JI By Krpal Sngh “Man’s only duty is to be ever grateful to God for His innumerable gifts and blessings.” THE JAP JI about the translator . Krpal Sngh, a modern Sant n the drect lne of Guru Nanak, was born n 1894 n the Punjab n Inda (now part of Pakstan). Hs long lfe, saturated wth love for God and humanity, brought peace and fulfillment to approximately 120,000 dscples, scattered all over the world. He taught the natural way to find God while living; and His life was the embodment of Hs teachngs. He made three world tours, was Presdent of the World Fellowshp of Relgons for four- teen years, and convened the World Conference on Unty of Man n February 1974, attended by relgous, socal and poltcal leaders from all over the world. He ded on August 21, 1974, in his eighty-first year, stepping out of his body in full consciousness; His last words were of love for His dis- cples. Hs lfe bears eloquent testmony that the age of the prophets is not over; that it is still possible for human beings to find God and reflect His will. v v INTRODUCTION THE JAP JI The Message of Guru Nanak Literal Translation from the Original Punjabi Text with Introduction, Commentary, Notes, and a Biographical Study of Guru Nanak By Krpal Sngh A RUHANI SATSANG® BOOK RUHANI SATSANG DIVINE SCIENCE OF THE SOUL v v THE JAP JI I have written books without any copyright—no rights reserved — because it is a Gift of God, given by God, as much as sunlight; other gifts of God are also free. -

Ecology and Ignatian Spirituality 41–44 José A

THE WAY a review of Christian spirituality published by the British Jesuits July 2018 Volume 57, Number 3 TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES OF SPIRITUAL GROWTH this issue of The Way is dedicated to the memory of Paul L. Younger (1962–2018) Illustration from a manuscript of Liber divinorum operum by Hildegard of Bingen, early thirteenth century THE WAY July 2018 Foreword 5–6 Striving for Perfection or Growing into Fruitfulness? 7–17 Christopher Chapman Any understanding of spiritual growth will be influenced by the images chosen to illustrate it. Is this growth more like climbing a ladder to ever-higher states of perfection, or slowly unfolding as a developing organism does? Christopher Chapman explores this question in terms of four stages of organic growth. The Light of Consciousness and the Light of Christ 19–30 Meredith Secomb Meredith Secomb is a clinical psychologist who has reflected deeply on the challenge of human suffering. In supporting her clients as they deal with difficult experiences, she has found that by sitting with these experiences in silence they find a luminous core within themselves, and that this in turn leads them to God. Here she describes this process, and considers its meaning. St Teresa of Jesus, Mental Prayer and the Humanity of Jesus 31–39 Joanna Farrugia St Teresa of Ávila advocated mental prayer for her Carmelite sisters at a time when this laid women open to suspicion from the Church authorities. Joanna Farrugia explains why this was important to Teresa, and how it was inextricably linked for her to a life dedicated to loving service of others. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

![UZR W]Zvd $*# ^`Cv E` Wcvvu`^](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8533/uzr-w-zvd-cv-e-wcvvu-848533.webp)

UZR W]Zvd $*# ^`Cv E` Wcvvu`^

* + 7!4 8 5 ( 5 5 VRGR '%&((!1#VCEB R BP A"'!#$#1!$"$#$%T utqBVQWBuxy( (*+,(-'./ ,2,23 0,-1$( ,-./ 31<O62!12!&/$.& @ /< '% 261&$/$ 42/1$/%-; <3 .1<&/.1%.& 23&6 %2 /$!-< 26-$&/ 6& -1$6&$%6 -1& 4$&61 31&!$!12$6-624<@ &$6/$ 2!<12/$ 2>&-%&!$< $2</4.=?- 4216&4% 1=426&.&4>$'&=3&4& / - !$%&' (() *99 :& (2 & 0 1&0121'3'1& " # $ 2342/1$ 2342/1$ s the new I-T portal con- tepping up efforts to bring its Atinued to have glitches and Scitizens back home, India on remained unavailable for two Sunday airlifted 392 people, consecutive days, the Finance besides some Afghan politi- Ministry “summoned” Infosys cians, from Kabul to New Delhi. 2342/1$ MD and CEO Salil Parekh on They were evacuated in three Monday to explain to Finance different flights of the Indian mid the Afghanistan crisis Minister Nirmala Sitharaman Air Force (IAF) and Air India. Aand India’s ongoing evac- the reasons for the continued Some more flights are planned uation exercise following the snags even after over two in the days to come to safely Taliban takeover of the coun- months of the site’s launch. bring back stranded Indian cit- try, Union Housing and Urban However, just ahead of the izens from Afghanistan. Affairs Minister Hardeep Singh meeting with Sitharaman, A team of Indian officials Puri on Sunday cited the evac- Infosys late on Sunday night is now based in Kabul to assist uations from Afghanistan to said that emergency mainte- those Indians who want to back the controversial nance on the website had been return home. -

The Five Dacoits the Five Perversions of Mind from the Path of the Masters by Julian Johnson Sant Kirpal Singh Ji, Hazur Baba Sawan Singh Ji, and Others

The Five Dacoits The Five Perversions of Mind From The Path of the Masters by Julian Johnson Sant Kirpal Singh Ji, Hazur Baba Sawan Singh Ji, and others We are constantly beset by five foes - passion, anger, greed, worldly attachments, and vanity. All these must be mastered, brought under control. You can never do that entirely until you have the aid of the Guru and are in harmonic relations with the Sound Current. But you can begin now, and every effort will be a step on the way. (Baba Sawan Singh, Spiritual Gems, 339) Swami Ji has said that we should not hesitate to go all out to still the mind. We do not fully grasp that the mind takes everyone to his doom. It is like a thousand-faced snake, which is constantly with each being; it has a thousand different ways of destroying the person. The rich with riches, the poor with poverty, the orator with his fine speeches – it takes the weakness in each and plays upon it to destroy him. (Sant Kirpal Singh Ji) ruhanisatsangusa.org/serpent.htm Contents Page: 1. The Five Perversions of Mind, from The Path of the Masters, by Julian Johnson 2. Biography of Julian Johnson, from Wikipedia 3. Lust– Julian Johnson 5. The Case for Chastity, Parts 1 & 2 from Sat Sandesh 6. Sant Kirpal Singh Ji on Chastity 7. Hazur Baba Sawan Singh 8. Anger– Julian Johnson 10. Anger Quotes 11. Sant Kirpal Singh on Anger 12. Baba Sawan Singh, Jack Kornfield 13. Greed– Julian Johnson 14. Greed Quotes 15. -

Political History of Merger of the Princely States : a Study of Cooch Behar

POLITICAL HISTORY OF MERGER OF THE PRINCELY STATES : A STUDY OF COOCH BEHAR A Thesis Submitted For The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Arts) of The University of North Bengal BY Senior Lecturer, Balurgh^VWOTiftefn's College m ?opt ^ iibrttijr Dr, LHlip Kumar Sarkar Controller of Examinations University of North Bengal .^J^. «fS J48356 C0^4TE^ITS Page No. Acknowledgement i-ii Preface lii-L'ii cipapter — I 1-32. PROLOGUE cipapter — II 33-54 FORMATION OF INDIAN STATE: AN OVERVIEW ci^afjter — III 55-74 THE COOCH BEHAR STATE IN THE NORTH EASTERN PERSPECTIVE ci^apter — IV 75-89 BRITISH POLICY TOWARDS THE INDIAN STATES WITH REFERENCE TO COOCH BEHAR (1757-1813) doapter — V 90-102 BRITISH POLICY TOWARDS THE INDIAN STATES WITH REFERENCE TO COOCH BEHAR (1813-1857) cl^apter — VI 103-119 BRITISH POLICY TOWARDS THE INDIAN STATES WITH REFERENCE TO COOCH BEHAR (1858-1919) cljapler — VII 120-160 BRITISH POLICY TOWARDS THE INDIAN STATES WITH REFERENCE TO COOCH BEHAR (1191-1950: THE PROCESS OF BARGAINING; C&^pter ~ VIII 161-207 A DETAILED STUDY OF MERGER OF A TINY PRINCELY STATE: COOCH BEHAR EXPERIENCE cf^apter — IX 208-232 EPILOGUE SefecL Bihlwgraplp^ 233-267 Page No. Appendix ~ I ^68-2.70 ARTICLES OF TREATY BETWEEN THE HON'BLE ENGLISH EAST INDIA COMPANY AND DURINDIR NARAYAN RAJAH OF COOCH BEHAR (1773) Appendix ~ II iyi-2.y^ THE FIRST TREATY WITH BHOOTAN (1774) Appendix —III 274-277 ASSURANCES OF THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA TO THE MAHARAJA OF COOCH BEHAR ON MERGER ISSUE Appendix — IV 278-282 MERGER AGREEMENT SIGNED ON 28TH AUGUST, 1949, BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA AND THE MAHARAJA OF COOCH BEHAR Appendix - V 283-290 ADDRESS OF DR. -

Biography of Babarao Savarkar

Biography of Babarao Savarkar www.savarkar.org Preface Ganesh Damodar Savarkar was a patriot of the first order. Commonly known as Babarao Savarkar, he is the epitome of heroism that is unknown and unsung! He was the eldest of the four Savarkar siblings - Ganesh or Babarao; Vinayak or Tatyarao, Narayan or Balarao were the three Savarkar brothers; they had a sister named Maina or Mai who was married into the Kale family. Babarao was a great revolutionary, philosopher, writer and organizer of Hindus. The following account is largely an abridged English version of Krantiveer Babarao Savarkar, a Marathi biography written by DN Gokhale, Shrividya Prakashan, Pune, second edition, pp.343, 1979. Some part has been taken from Krantikallol (The high tide of revolution), a Marathi biography of Veer Vinayak Damodar (Tatyarao) Savarkar’s revolutionary life by VS Joshi; Manorama Prakashan, 1985. Details of the Cellular jail have been taken from Memorable Documentary on revolutionary freedom fighter Veer Savarkar by Prem Vaidya, Veer Savarkar Prakashan, 1997 and also from the website www.andamancellularjail.org. Certain portions dealing with Babarao’s warm relations with Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh founder Dr. Keshav Baliram Hedgewar have been translated from Dr. Hedgewar’s definitive Marathi biography by Narayan Hari Palkar; Bharatiya Vichar Sadhana, Pune, fourth edition, 1998. Pune, 28 May 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ...........................................................................................1 1 Early childhood.......................................................................7 1.1 Babarao and Tatyarao: ......................................................................... 8 2 Initial Revolutionary Activities...............................................10 2.1 Liberation of the soul or liberation of the motherland? ........................ 10 2.2 Mitramela and Abhinav Bharat: ........................................................... 11 2.3 First-ever public bonfire of foreign goods: ..........................................