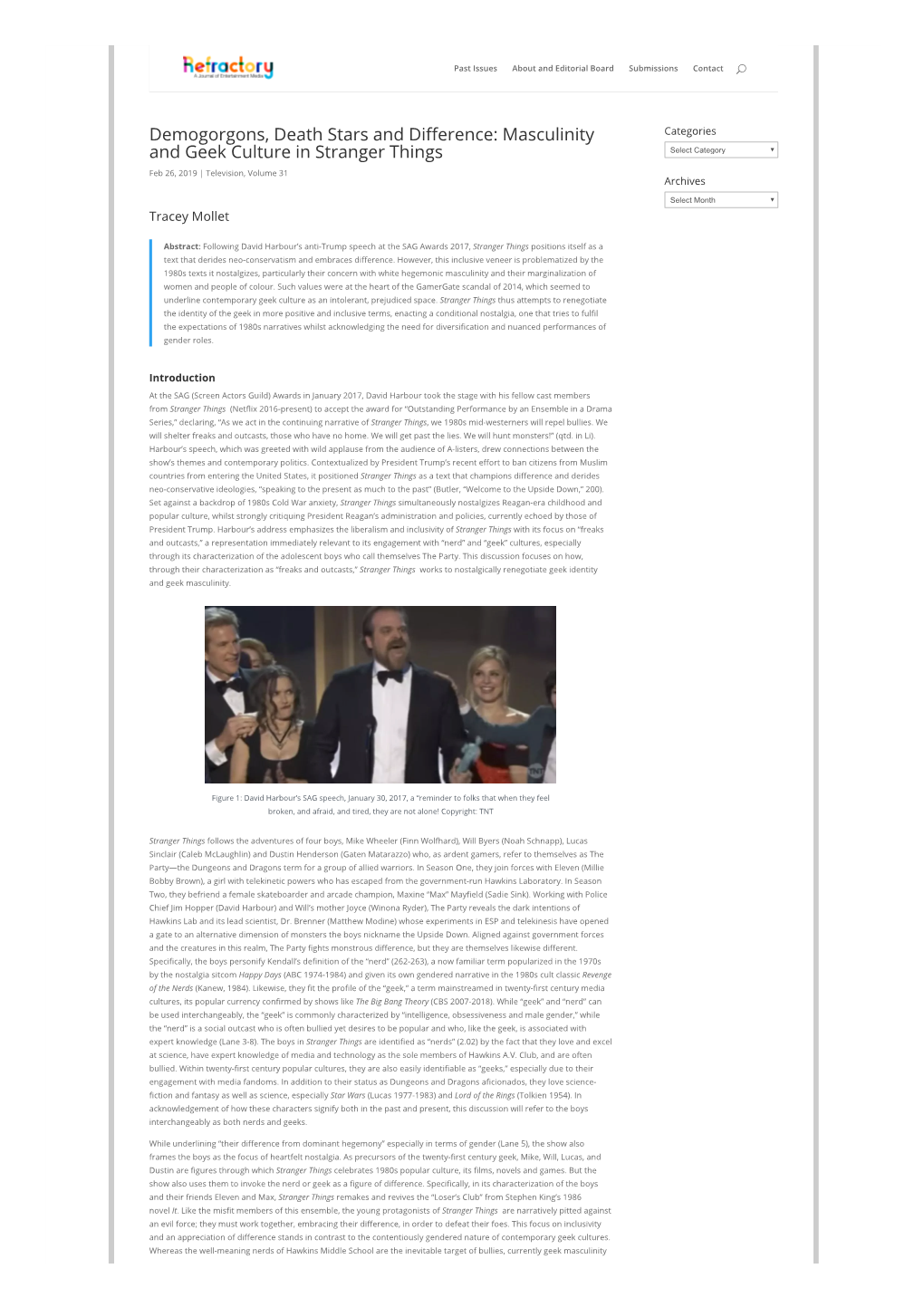

Masculinity and Geek Culture in Stranger Things

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

Bull Dogs' Quintessential Team Player

BULL DOG OCT. 1 - NOV. 4, 2018 BULLETIN VOL. 8, ISSUE 3 NEWS AND INFORMATION ABOUT COLUMBUS NORTH HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETICS IN THIS ISSUE Fall Scoreboard ............. 2 Football .......................... 4 Boys Soccer .................. 9 Girls Soccer ................... 11 Cross Country ................ 15 Girls Golf ........................ 17 Boys Tennis ................... 19 Volleyball ....................... 23 Cheerleaders ................. 25 Booster Club .................. 29 Athletic Staff .................. 31 MR. INTENSITY: Kevin Lin displays ferocity while remaining analytical while competing for the Columbus North boys’ tennis team. The senior – a two-time team most valuable player – carries a 12-5 record this season at No. 1 singles entering regional competition. BULL DOGS’ QUINTESSENTIAL TEAM PLAYER FORE!: Sophomore Nathaly Munnicha earned Columbus North senior thrives on court, excels in leadership role for boys’ tennis team all-state honors girls golf in 2018. CN GIRLS ole model. Kevin Lin. Lin, who hopes for a career in sports medicine GOLF PLACES Kevin Lin. Role model. or as an orthopedic surgeon, said he strives to R The Columbus North senior boys’ bring proper focus and footwork to each match. SEVENTH AT tennis player and the concept go hand-in-hand, “I’m intense when I play,” said Lin, who is STATE MEET according to Bull Dogs coach Kendal Hammel. considering Indiana, Purdue, Columbia, Michigan Lin has been the epitome of a quality player and Duke as possible college choices. “I try to Sophomore Nathaly Munnicha shot throughout his career, compiling a 58-31 play 100 percent all the time and try not to be a 78 on Sept. 29 for a two-round total record in varsity matches as four-year varsity sloppy or lazy. -

Undercover Footage from Sydney Slaughterhouse Released As NSW & Federal Govt Seek to Criminalise Whistleblowing

MEDIA RELEASE – 29 AUGUST 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘Horrific but legal’ undercover footage from Sydney slaughterhouse released as NSW & Federal Govt seek to criminalise whistleblowing Animal rights organisations Aussie Farms and Animals Within have released new footage captured by a hidden body-worn camera at the Picton Meatworx (formerly Wollondilly Abattoir), a multi-species slaughterhouse south of Sydney, amid efforts by the NSW and Federal Governments to severely increase penalties for activists who expose animal cruelty. View the footage: 8 minute summary edit: https://www.aussiefarms.org.au/videos?id=yq7rtdnf07 25 minute full edit: https://www.aussiefarms.org.au/videos?id=pneynwbwc9 The footage includes: the use of excruciating carbon dioxide gas chambers on pigs, goats and sheep; repeated failure of captive bolt stunning, with one pig shot eight times while screaming in pain; twisting and breaking of cows’ tails to force them to walk into the knockbox; animals regularly witnessing those before them being killed and consequently trying to escape. It was recorded by a university student undertaking a placement at the facility as part of their animal science degree. Chris Delforce, Executive Director of Aussie Farms and director of Dominion: “This is some of the most damning Australian footage I’ve ever seen, and yet, it’s completely legal. There are very minimal laws in place to protect animals in facilities like these, which is the complete opposite to what most consumers are led to believe; while there’s a general offence for animal cruelty in the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act (POCTA) NSW, farms and slaughterhouses are exempt from this if they follow basic codes of practice which effectively legalise cruelty that regular citizens wouldn’t be able to get away with.” “The code of practice relating to slaughterhouses is only a model code, intended as non-enforceable guidelines for states and territories to develop their own legislation, but 18 years later none have done so. -

Musikliste Zu Terra X „Unsere Wälder“ Titel Sortiert in Der Reihenfolge, in Der Sie in Der Doku Zu Hören Sind

Z Musikliste zu Terra X „Unsere Wälder“ Titel sortiert in der Reihenfolge, in der sie in der Doku zu hören sind. Folge 1 MUSIK - Titel CD / Interpret Composer Trailer Terra X Trailer Terra X Main Title Theme – Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Westworld Ramin Djawadi Dr. Ford Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Ramin Djawadi Photos in the Woods Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Eleven Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Race To Mark's Flat Bridget Jones's Baby / Craig Armstrong Craig Armstrong Boggis, Bunce and Fantastic Mr. Fox / Alexandre Desplat Alexandre Desplat Bean Hibernation Pod 1625 Passengers / Thomas Newman Thomas Newman Jack It Up Steve Jobs / Daniel Pemberton Daniel Pemberton The Dream and the Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Letters Theodore Shapiro Reporters Swarm Confirmation / Harry Gregson Williams Harry Gregson Williams Persistence Burnt / Rob Simonsen Rob Simonsen Introducing Howard Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Inlet Theodore Shapiro The Dream and the Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Theodore Shapiro Letters Main Title Theme – Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Westworld Ramin Djawadi Fell Captain Fantastic / Alex Somers Alex Somers Me Before You Me Before You / Craig Armstrong Craig Armstrong Orchestral This Isn't You Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon The Skylab Plan Steve Jobs / Daniel Pemberton Daniel Pemberton Photos in the Woods Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Speight Lived Here The Knick (Season 2) / Cliff Martinez Cliff Martinez This Isn't You Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon 3 Minutes Of Moderat A New Beginning Captain Fantastic / Alex Somers Alex Somers 3 Minutes Of Moderat The Walk The Walk / Alan Silvestri Alan Silvestri Dr. -

Stranger Things 2 *

WONDER VIEW Episode #209 "Chapter Nine: The Gate" by The Duffer Brothers Directed by The Duffer Brothers PRODUCTION DRAFT April 17, 2017 (WHITE) April 30, 2017 (BLUE) Copyright © 2017 Storybuilders, LLC. All rights reserved. No portion of this script may be performed, published, reproduced, sold, or distributed by any means or quoted or published in any medium, including on any website, without the prior written consent of Storybuilders, LLC. Disposal of this script copy does not alter any of the restrictions set forth above. Episode #209 04/30/17 WONDER VIEW "Chapter Nine: The Gate" REVISION HISTORY DATE COLOR PAGES PUBLISHED 04/17/17 PRODUCTION DRAFT FULL SCRIPT 04/30/17 (BLUE) CAST, SETS, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15, 15A, 28, 30, 37, 44, 45, 48, 49, 49A, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 55A, 63, 64, 67, 70/71 8FLiX.com SCREENPLAY DATABASE FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Episode #209 04/30/17 WONDER VIEW "Chapter Nine: The Gate" CAST LIST JOYCE BYERS POLICE CHIEF JIM HOPPER MIKE WHEELER NANCY WHEELER JONATHAN BYERS ELEVEN LUCAS SINCLAIR DUSTIN HENDERSON KAREN WHEELER WILL BYERS STEVE HARRINGTON MAX MAYFIELD BILLY HARGROVE (fka BILLY MAYFIELD) * DR. SAM OWENS TED WHEELER MURRAY BAUMAN * * MR. CLARKE CLAUDIA HENDERSON ERICA SINCLAIR MRS. HOLLAND MR. HOLLAND SUSAN HARGROVE (fka SUSAN MAYFIELD) * * * * CUTE GIRL STACEY TV NEWS ANCHOR MIDDLE SCHOOL BOY #1 * * 8FLiX.com SCREENPLAY DATABASE FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Episode #209 04/30/17 WONDER VIEW "Chapter Nine: The Gate" SET LIST INTERIORS EXTERIORS BYERS HOUSE BYERS HOUSE HALLWAY BACK YARD/SHED JONATHAN'S ROOM DRIVEWAY -

Exclusive! See the First Stills of the New Stranger Things Character You Will Fall in Love With

DON’T MISS OUT! STUDENTS GET 10% OFF ALL. YEAR. ROUND. FIND OUT MORE MENU CINEMA & TV Exclusive! See The First Stills Of The New Stranger Things Character You Will Fall In Love With 3rd July 2019 Stranger Things 3 nally launches on Netix tomorrow! The new season promises lots of summer vibes, exciting twists and turns and some brand new characters. One of them is portrayed by Maya Hawke, Uma Thurman and Ethan Hawke’s daughter, and we have some exclusive stills to share of her in the show you’ve seen here rst… Meet Robin, a cool new girl who is Steve Harrington’s colleague at the Scoops Ahoy ice cream parlour in Hawkins’ rst premium shopping centre, the Starcourt Mall. Tune in tomorrow to nd out what she’s all about… Stranger Things 3 is coming to Netix on 4th July 2019. Find out what else to watch on Netix this July… PREVIOUS ARTICLE NEXT ARTICLE RECENT POSTS FEATURED FEATURED CULTURE What’s On Our Topshop 5 Ways to Style The It’s Aquarius Season! Wishlist This Payday Latest Trending Colour Here’s Everything You Green Need To Know TRENDING STORIES CINEMA & TV FEATURED AWARD SEASON The Netix Releases To 5 Simple Things To Do To How, When And Where Watch This January 2020 Start The New Year In The Watch The Oscar Right Way Nominated Films Of 20 GO TO TOPSHOP.COM NEW IN CLOTHING DRESSES JEANS SHOES BAGS & ACCESSORIES TOPSHOP ON THE GO FIND OUT MORE FIND YOUR NEAREST STORE STAY IN THE KNOW TERMS OF USE PRIVACY POLICY SIGN UP TO EMAILS SHOP TOPSHOP.COM. -

No. 3 2018 Messengers from the Stars: on Science Fiction and Fantasy No

No. 3 2018 Messengers from the Stars: On Science Fiction and Fantasy No. 3 – 2018 Editorial Board | Adelaide Serras Ana Daniela Coelho Ana Rita Martins Angélica Varandas João Félix José Duarte Advisory Board | Adam Roberts (Royal Holloway, Univ. of London, UK) David Roas (Univ. Autónoma de Barcelona, Spain) Flávio García (Univ. do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) Henrique Leitão (Fac. de Ciências, Univ. de Lisboa, Portugal) Jonathan Gayles (Georgia State University, USA) Katherine Fowkes (High Point University, USA) Ljubica Matek (Univ. of Osijek, Croatia) Mª Cristina Batalha (Univ. do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) Susana Oliveira (Fac. de Arquitectura, Univ. de Lisboa, Portugal) Teresa Lopez-Pellisa (Univ. Autónoma de Barcelona, Spain) Copy Editors | Ana Rita Martins || David Klein Martins || João Félix || José Duarte Book Review | Diana Marques || Igor Furão || Mónica Paiva Editors Translator | Diogo Almeida Photography | Thomas Örn Karlsson Site | http://messengersfromthestars.letras.ulisboa.pt/journal/ Contact | [email protected] ISSN | 2183-7465 Editor | Centro de Estudos Anglísticos da Universidade de Lisboa | University of Lisbon Centre for English Studies Alameda da Universidade - Faculdade de Letras 1600-214 Lisboa - Portugal Messengers from the Stars: On Science Fiction and Fantasy Guest Editors Martin Simonson Raúl Montero Gilete Co-Editors No. 3 Angélica Varandas José Duarte TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 5 GUEST EDITORS: MARTIN SIMONSON & RAÚL MONTERO GILETE 5 MONOGRAPH SECTION 9 A DEAL WITH THE DEVIL?: ZOMBIES VS. -

'Grapes of Wrath' Brought to Life!

The Sun Devils’ Advocate Volume XLI, Number 7 Kent Denver School, 4000 East Quincy Avenue, Englewood, CO 80110 November 17, 2017 ‘Grapes Of Wrath’ Brought To Life! The KDS Joad Family heads West to kook for work. Photo by Cordelia Lowrey Boys Tennis ‘Stranger Things’ #MeToo Wins State Season 2 See Page 8 See Page 11 See Page 13 News Las Vegas Pushes For Gun Regulations eral public, without any responsible measures by Henry Rogers or safeguards, and which the killer foreseeably used to such horrific results.” Following the tragic mass shootings in Las Vegas and San Antonio, there has been a recent Since the filing of the lawsuit, Democrats push from many gun control groups to see a in Congress have proposed legislation to ban change in gun regulation from Congress. After Bump Stocks, and both President Trump and the Las Vegas shooting, a powerful gun control the National Rifle Association (NRA) have group filed a lawsuit against the manufacturers been open to the idea of greater regulation. of ‘Bump Stocks,’ an instrument which was be- Unfortunately, the future does not hold any lieved to have been used by Stephen Paddock, promise that there will be any major changes the Las Vegas shooter, from the 32nd floor of regarding gun safety regulations at this time, Mandalay Bay Hotel. The purpose of a ‘Bump due to the NRA’s powerful lobbying influence Stock’ is to allow semi automatic guns to rapid on political leaders. fire bullets, making it more akin to automatic The NRA and Congress’s inability to im- weapons or machine guns. -

Stranger Things Episode Guide Episodes 001–025

Stranger Things Episode Guide Episodes 001–025 Last episode aired Thursday July 04, 2019 www.netflix.com c c 2019 www.tv.com c 2019 www.netflix.com c 2019 www.tvtropes.org c 2019 strangerthings. fandom.com The summaries and recaps of all the Stranger Things episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http:// www.netflix.com and http://www.tvtropes.org and http://strangerthings.fandom.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ! This booklet was LATEXed on July 8, 2019 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.62 Contents Season 1 1 1 Chapter One: The Vanishing of Will Byers . .3 2 Chapter Two: The Weirdo on Maple Street . .7 3 Chapter Three: Holly, Jolly . 11 4 Chapter Four: The Body . 15 5 Chapter Five: The Flea and the Acrobat . 19 6 Chapter Six: The Monster . 23 7 Chapter Seven: The Bathtub . 27 8 Chapter Eight: The Upside Down . 29 Season 2 33 1 Chapter Nine: Madmax . 35 2 Chapter Ten: The Boy Who Came Back to Life . 39 3 Chapter Eleven: The Pollywog . 43 4 Chapter Twelve: Will the Wise . 45 5 Chapter Thirteen: Dig Dug . 47 6 Chapter Fourteen: The Spy . 49 7 Chapter Fifteen: The Lost Sister . 51 8 Chapter Sixteen: The Mind Flayer . 53 9 Chapter Seventeen: The Gate . 55 Season 3 59 1 Chapter One: Suzie, Do You Copy? . 61 2 Chapter Two: The Mall Rats . 63 3 Chapter Three: The Case of the Missing Lifeguard . -

Stranger Things | Dialogue Transcript | S2:E8

CREATED BY Matt Duffer | Ross Duffer EPISODE 2.08 “Chapter Eight: The Mind Flayer” An unlikely hero steps forward when a deadly development puts the Hawkins Lab on lockdown, trapping Will and several others inside. WRITTEN BY: Matt Duffer | Ross Duffer DIRECTED BY: Matt Duffer | Ross Duffer ORIGINAL BROADCAST: October 27, 2017 NOTE: This is a transcription of the spoken dialogue and audio, with time-code reference, provided without cost by 8FLiX.com for your entertainment, convenience, and study. This version may not be exactly as written in the original script; however, the intellectual property is still reserved by the original source and may be subject to copyright. MAIN EPISODE CAST Winona Ryder ... Joyce Byers David Harbour ... Jim Hopper Finn Wolfhard ... Mike Wheeler Millie Bobby Brown ... Eleven Gaten Matarazzo ... Dustin Henderson Caleb McLaughlin ... Lucas Sinclair Noah Schnapp ... Will Byers Sadie Sink ... Max Mayfield Natalia Dyer ... Nancy Wheeler Charlie Heaton ... Jonathan Byers Joe Keery ... Steve Harrington Dacre Montgomery ... Billy Hargrove Cara Buono ... Karen Wheeler Sean Astin ... Bob Newby Paul Reiser ... Sam Owens Will Chase ... Neil Hargrove Helen Abell ... Radar Tech Brian Brightman ... M.P. Guard #1 Kristopher Charles ... M.P. Guard #2 Joe Davison ... Nerdy Tech Jennifer Marshall ... Susan Hargrove 1 00:00:06,798 --> 00:00:08,675 [low growling] 2 00:00:26,568 --> 00:00:28,570 [growling] 3 00:00:32,866 --> 00:00:33,950 Mother of God. 4 00:00:37,037 --> 00:00:38,496 [growling softly] 5 00:00:45,211 --> 00:00:47,130 [snarling] 6 00:00:51,176 --> 00:00:53,720 It's.. -

Los Nominados a La 24Ta Edición De Los Premios Del Sindicato De Actores De Cine Han Sido Anunciados

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Rosalind Jarrett Sepulveda [email protected] (424) 309-1400 Los nominados a la 24ta edición de los Premios del Sindicato de Actores de Cine han sido anunciados. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- La ceremonia se transmitirá en vivo el domingo 21 de enero de 2017, en TNT y TBS a las 8pm (ET) 5pm (PT). LOS ÁNGELES (13 de diciembre de 2017) – Los nominados a la 24ta edición de los Premios del Sindicato de Actores de Cine por sus excepcionales actuaciones individuales y como elenco en cine y televisión en 2017, así como los nominados por sus excepcionales actuaciones como elencos de dobles de acción en cine y televisión fueron anunciados esta mañana en el SilverScreen Theater del Pacific Design Center en West Hollywood. La Presidenta de SAG-AFTRA, Gabrielle Carteris, presentó a Olivia Munn (X-Men Apocalypse, The Predator) y Niecy Nash (Claws, The Soul Man), quienes anunciaron los nominados para los Premios de este año, a transmitirse en vivo a través de TNT, TBS, truTV, sagawards.tntdrama.com, truTV.com y sagawards.org, en las aplicaciones móviles de TNT y TBS, y los canales en redes sociales de TNT y TBS en Facebook, Twitter y YouTube. Poco antes, la presidenta del Comité de los Premios SAG, JoBeth Williams, y la miembro del Comité, Elizabeth McLaughlin, anunciaron a los nominados como elencos de dobles de acción durante una transmisión en línea, en vivo a través de tntdrama.com/sagawards y sagawards.org. Repeticiones de ambos anuncios están disponibles para su visualización en tntndrama.com/sagawards y sagawards.org. La lista completa de los nominados a la 24ta edición anual de los Premios del Sindicato de Actores de Cine se encuentra a continuación de este aviso. -

Stranger Things 2 Soundtrack Free Download Stranger Things Soundtracks | Free Listen to Stranger Things Soundtrack MP3 Songs

stranger things 2 soundtrack free download Stranger Things SoundTracks | Free Listen to Stranger Things Soundtrack MP3 songs. If you are a thrill seeker, you must know Stranger Things , an American science fiction horror television series. The first season demonstrates the investigation and search for a boy disappearing in the supernatural events. The second season illustrates the continual story to return to the normality and describes the results from the first season. Like other horror movies or television series, Stranger Things also depicts the reflection of people's inside fear. In the television series, you can see many retro elements in the 1980’s which captures the audience’s spirit and memory of the time. It combines children with supernatural topics which makes the television series one of the most popular phenomenal television series. Additionally, the actors' performance is natural and outstanding, which enables the television series to fully convey what it plans to say. Therefore, this television series gains great success, winning nominations at Golden Globe Award and accolades at Screen Actors Guild Award. Part 1. Stranger Things Season 1 Soundtracks Full List. Apart from the fabulous performance of actors which received awards, Stranger Things soundtrack garners the audience's love and praise. Below is Stranger Things season 1 soundtrack for free download. Part 2. Stranger Things Season 2 Soundtracks Full List. Stranger Things soundtrack season 2 also attracts a large number of fans. Like in the season 1 full playlist, you can click on the first link to appreciate the song and second link to download if you think it is a pleasant song.