Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cryptologic Quarterly, 2019-01

Cryptologic Quarterly NSA’s Friedman Conference Center PLUS: Vint Hill Farms Station • STONEHOUSE of East Africa The Evolution of Signals Security • Mysteries of Linguistics 2019-01 • Vol. 38 Center for Cryptologic History Cryptologic Quarterly Contacts. Please feel free to address questions or comments to Editor, CQ, at [email protected]. Disclaimer. All opinions expressed in Cryptologic PUBLISHER: Center for Cryptologic History Quarterly are those of the authors. Th ey do not neces- CHIEF: John A. Tokar sarily refl ect the offi cial views of the National Security EXECUTIVE EDITOR: Pamela F. Murray Agency/Central Security Service. MANAGING EDITOR: Laura Redcay Copies of Cryptologic Quarterly can be obtained by ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Jennie Reinhardt sending an email to [email protected]. Editorial Policy. Cryptologic Quarterly is the pro- fessional journal for the National Security Agency/ Central Security Service. Its mission is to advance knowledge of all aspects of cryptology by serving as a forum for issues related to cryptologic theory, doc- trine, operations, management, and history. Th e pri- mary audience for Cryptologic Quarterly is NSA/CSS professionals, but CQ is also distributed to personnel in other United States intelligence organizations as well as cleared personnel in other federal agencies and departments. Cryptologic Quarterly is published by the Center for Cryptologic History, NSA/CSS. Th e publication is de- signed as a working aid and is not subject to receipt, control, or accountability. Cover: “Father of American cryptology” William Friedman’s retirement ceremony in the Arlington Hall Post Theater, Arlington, VA, 1955. Lieutenant General Ralph Canine is at left, Solomon Kullback is seated left, Friedman is second from right, and Director of Central Intelligence Allen Dulles is at far right. -

Annual Historical Review Us Army Intelligence and Security Command Fiscal Year 1982

Description of document: Annual Historical Review, U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM), FY 1982 Request date: 10-June-2008 Released date: 06-August-2018 Posted date: 17-September-2018 Source of document: Freedom Of Information Act Request Commander, INSCOM ATTN: IAMG-C-FOI 2600 Ernie Pyle St. Fort Meade, MD 20755-5995 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY UNITED STATES ARMY INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY COMMAND FREEDOM OF INFORMATION/PRIVACY OFFICE FORT GEORGE G. MEADE, MARYLAND 20755-5995 AUG O 6 2018 Freedom of Information/ Privacy Office This is in further response to your Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request of June 1O, 2008, for the INSCOM Annual History FY 1982 and supplements our letter of March 11, 2015. -

Vint Hill Farms Station: Further Delineation of VOC Contamination

GSA Contract No. GS 10F-0048J Delivery Order No. DACA31-01-F-0142 VINT HILL FARMS STATION Further Delineation of VOC Contamination in Overburden at AREE 34 – Work Plan FINAL DOCUMENT NOVEMBER 2003 VINT HILL FARMS STATION FURTHER DELINEATION OF VOC CONTAMINATION IN OVERBURDEN AT AREE 34 FINAL DOCUMENT Nora A. Zirps, P.E. Project Manager Prepared by: SHAW ENVIRONMENTAL, INC. 2113 EMMORTON PARK ROAD EDGEWOOD, MARYLAND 21040 With Assistance from: COLUMBIA TECHNOLOGIES 1450 SOUTH ROLLING ROAD BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 21227 TRI-CORDERS ENVIRONMENTAL, INC. 1800 OLD MEADOW ROAD MCLEAN, VIRGINIA 22102 NOVEMBER 2003 Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704- 0188), Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED November 2003 Further Delineation of VOC Contamination in Overburden at AREE 34 – Work Plan, November 2003 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Further Delineation of VOC Contamination in Overburden at AREE 34 – Work Plan GSA Contract No. GS 10F-0048J (FDVCO-WP), Vint Hill Farms Station, Final Document Delivery Order No. -

Corks of History

PAST IS PROLOGUE ]\ :': \ ':. ,,, ,.: \ .,.|: ::.., I Changingthe Corks of History WARRENTON, Vo.- Inthe same VHFS was "one of the pri- space where loquacious visitors mary sources ofAllied in- now press wine glasses to their terception, decryption, and Iips, soldiers decades earlier translation of coded Japanese were forced to remain tight- signals during World War II," lipped. That's because Vint HilI Jason HalI wrcle in lhe Ameri - Craft Winery was a signals in- can Intelligence Journalin 2016. telligence facility during World HaIl is executive director of The War II. ColdWar Museum, which is ad- Wine, like history, has hints jacentto the winery atVint HilI. ofmystery. VHFS formerly encompassed often was shrouded in secrecy. More than 60 yearsbefore it the entire area. But in 1943, an antenna on site housed atastingroom and oak Alongwith a sister station, was used to intercept a message barrels, the winery was part of a T\ro Rock Ranch in Californi4 from the Japanese ambassador 700-acrefarm. VHFS was the main intercept in Berlin to his superiors in The Army purchased the site station duringlvwll. Those who Tolryo, according to a historical in 19 42, and Vint Hiil Farms worked at the monitoring sta- account cite d in The Wash- Station (VIIFS) was created by tion - inside an old barn exterior ington Post 50 years later. The the Army's Signal Intelligence where the winery is now located message subsequently was said Service in the strme year, accord- - gathered signals intelligence by Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower ing to National Security Agiency duringWWll andbeyond. to have impacted the following documentation. -

Environmental Assessment for Construction of a Veterans Care Center in Fauquier County, Virginia

Environmental Assessment for Construction of a Veterans Care Center in Fauquier County, Virginia May 2017 Virginia Department of Veterans Services Office of the Commissioner 101 North 14th Street, 17th Floor Richmond, VA 23219 This page intentionally left blank. Environmental Assessment: Construction of a Veterans Care Center May 2017 Vint Hill, Fauquier County, Virginia Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................. i Acronyms and Abbreviations ........................................................................................................ iv Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Project Background .............................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Purpose and Need ................................................................................................................. 2 2.0 ALTERNATIVES..................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. Development of Alternatives ............................................................................................... 5 2.2. Alternatives Retained for Detailed Analysis ....................................................................... -

Fauquier County Regional Water Supply Plan

Fauquier County Regional Water Supply Plan Submitted for: Fauquier County, the Town of Remington, and the Town of The Plains Fauquier County Office of Community Development September 29, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS TEXT Introduction 1 Section I-Existing Water Sources 9-VAC 25-780-70 4 Section II-Existing Water Use 9-VAC 25-780-80 26 Section III-Existing Resource Conditions 9-VAC 25-780-90 66 Section IV-Projected Water Demand 9-VAC 25-780-100 83 Section V-Water Demand Management Actions 93 V.A-Water Demand Management Information Worksheet 9-VAC 25-780-110 94 V.B-Drought Response and Contingency 9-VAC 25-780-120 106 Section VI-Statement of Needs 9-VAC 25-780-130 113 REFERENCES FIGURES Figure 1.1- Service Districts of Fauquier County Figure 1.2- Existing Wells in Fauquier County Figure 1.3- E-911 Address Points in Fauquier County (2009) Figure 1.4- E-911 Address Points and Existing Wells (2009) Figure 1.5- Public Water Systems in Fauquier County Figure 1.6- E-911, Public Water Systems, and Watersheds- Marshall Service District Figure 1.7- E-911, Public Water Systems, and Watersheds- Warrenton Service District Figure 1.8- E-911, Public Water Systems, and Watersheds- New Baltimore Service District Figure 1.9- E-911, Public Water Systems, and Watersheds- Remington Service District Figure 1.10- E-911, Public Water Systems, and Watersheds- New Baltimore Service District Figure 1.11- E-911, Public Water Systems, and Watersheds- Opal Service District Figure 1.12- E-911, Public Water Systems, and Watersheds- Catlett Service District Figure 1.13- E-911, -

In This Issue

Summer/Fall 2017 In This Issue: THE COLD WAR MUSEUM – Letter from the Chairman......................................................2 – Letter from the Executive Director........................................2 – Operations Team and Museum Activities.............................3-19 – Midwest Chapter...................................................................20 – Founding Member List……………………………………………………….21-26 VETERANS ASSOCIATIONS, MEETINGS, REUNIONS and UPDATES.......27 COLD WAR NEWS, PUBLICATIONS AND EVENTS……………………………….28 IN MEMORIAM…………………………………………………………………………………30 THE COLD WAR MUSEUM – Founding Member Information…………….31 About The Cold War Museum Founded in 1996 by Francis Gary Powers, Jr. and John C. Welch, The Cold War Museum is dedicated to preserving Cold War history and honoring Cold War Veterans. For more information, call 540-341-2008, go online to www.coldwar.org, or write The Cold War Museum, P.O. Box 861526 Vint Hill, VA 20187. To contact The Cold War Times or to submit articles for future issues, email the editor at [email protected] or visit www.coldwartimes.com. The opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of Cold War Times, The Cold War Museum, and/or their respective Boards. Cold War Times Newsletter Summer/Fall 2017 Page 1 of 31 Letter from the Chairman Charles Ray Chairman Greetings. You’ll note from the items in this issue that The Museum has been a busy place since our last newsletter. Our Executive Director and the volunteer staff have been active in providing information and education about the Cold War to ever-increasing audiences, and we’ve received extensive media coverage. Our series of presentations by experts and participants in pivotal events of the era are popular and well attended. I must stress, however, that this has all been accomplished by volunteers, and on an extremely limited budget. -

Annual Historical Review, U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM), FY 1987

Description of document: Annual Historical Review, U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM), FY 1987 Request date: 10-June-2008 Released date: 08-April-2015 Posted date: 18-May-2015 Source of document: Freedom Of Information Act Request Commander, INSCOM ATTN: IAMG-C-FOI 4552 Pike Road Fort Meade, MD 20755-5995 Fax: (301) 677-2956 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY UNITED STATES ARMY INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY COMMAND FREEDOM OF INFORMATION/PRIVACY OFFICE FORT GEORGE G. MEADE, MARYLAND 20755-5995 Freedom of Information/ Privacy Office 0 8 APR 2015 This is in further response to your Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request of June 1O, 2008, requesting the mandatory declassification review of the INSCOM Annual History volumes for FY 1977 through FY 1997 (our case numbers #0578F-08 through #0598F-08) and supplements our response of March 11, 2015. -

A World War II German Army Field Cipher and How We Broke It

i I I ' UNCLASSIFIED A World War II German Army Field Cipher and How We Broke It CHARLES DAVID In 1942 the U.S. Army Signal Corps was looking for college grad~ates to train in radar work, which was then new and promising. I enlisted, and after0 six months of pre-radar courses in calculus, physics, chemistry, and radio theory at Rutgers University, I found myself in Camp Crowder, Missouri, the Signal Corps basic training center. Once I was there, a classification sergeant informed me that Camp Murphy, the radar facility in Florida, was overcrowded and that I'd be assigned to some other training. Checking my academic record and Army Classification Test score, he suddenly asked me if I had ever heard of "cryptography." As he thumbed through his manual, my memory reverted to a cryptanalysis course that my fiancee had taken at Brooklyn College, given by Professor Jack Wolfe of the math department. She and I would sit in a sunny meadow in Prospect Park, and I helped with the frequency counts. My reverie was broken by the information that I was to be sent to Vint Hill Farms Station, near Warrenton, Virginia - close enough to my New York home and my wife-to-be to please me no end. Vint Hill was an unusual army camp - in a bucolic setting, with evergreen trees surrounding the barracks and woods all around. It was a hush-hush place, and we were constantly warned to keep it so. One of its two parts was devoted to cryptanalysis studies, and the other was a working radio facility. -

MEDIA KIT Press Contact: Mitch Neitzey, EFO

MEDIA KIT Press contact: Mitch Neitzey, EFO Capital Management, Inc. (202) 659-3000 Vint Hill: An Overview Vint Hill is one of the premier business locations in the Washington, D.C metropolitan area. It offers a diverse base of affordable commercial real estate, including land, office space or warehouse space. Located in Eastern Fauquier County, the Vint Hill community offers a highly skilled workforce and balances quality of life with easy access to the nation’s capital, Northern Virginia and Washington Dulles International Airport. Learn more at www.vinthill.com. Vint Hill Today Since acquiring the majority of Vint Hill’s remaining undeveloped land from VHEDA in 2014, EFO Capital Management-backed Vint Hill Village has advanced the authority’s mission to create a thriving, mixed-use business and residential hub in eastern Fauquier County. Working with county leaders and the community, EFO Capital Management continues to lead the effort to transform Vint Hill into a regional hub and job creation center. A variety of businesses and organizations have put down roots at Vint Hill in the last several years, including a cloud- computing company, community college, beauty salon, custom cabinet-maker, brewery, and winery. Dozens of others have offices in Vint Hill, and more businesses have made plans to locate in the growing community. Northern Virginia Veterans Care Center Site Selection On June 1, 2016, Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe announced that the Commonwealth has chosen a site in Fauquier County as the location for a new Veterans Care Facility. The facility will be located in Vint Hill, the former U.S. -

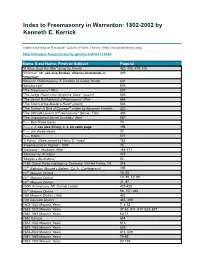

Index to Freemasonry in Warrenton: 1802-2002 by Kenneth E. Kerrick

Index to Freemasonry in Warrenton: 1802-2002 by Kenneth E. Kerrick Index courtesy of Fauquier County Public Library (http://fauquierlibrary.org) http://innopac.fauquiercounty.gov/record=b1119284 Name (Last Name, First) or Subject Page(s) "A Rose Upon the Altar" (play) by Claudy 420, 435, 479, 515 "Charmie", Mr. see also Sinclair, Charles Armistead, Jr. 449 "Charmie" "Masonic Philanthropies: A Tradition of Caring" (book) 631 "Missing Link" 575 "The Freemasons" (film) 537 "The Lodge Room Over Simpkins' Store" (poem) 605 "The Secret Brotherhood of Freemasons" (film) 566 "The Touch of the Master's Hand" (poem) 546 "The Turkey- A 'Bird of Courage'" written by Benjamin Franklin 332 "The Ultimate Lesson of Freemasonry" (Movie / Film) 408 "The Unexplained Secret Societies" (film) 567 ?----, Ben (freed slave) 73 ?----, J. J. see also Silvey, J. J. on same page 194 ?----, Jim (freed slave) 73 ?----, Hiram 577 “5 Points” (Store owned by Henry C. Yates) 183 “Freemasonry in Virginia”, 1936 28 “Galloway – Nusbaum Affair” 165-171 “Mammy” by Al Jolson 247 “Morgan’s Illustrations” 54 118th Signal Radio Intelligence Company, Vint Hill Farms, VA 314 12 th Battalion (Brooke’s Battery, Co. A., Confederacy) 195 12 th Masonic District 16, 66 13 th Masonic District 10, 35, 42, 89 14 th Masonic District 31, 97 150th Anniversary (Mt. Carmel Lodge) 427-428 15 th Masonic District 68, 107, 388 15th Masonic District (15A) 402 17th Capitular District 485, 499 1803-1823 Masonic Years 7, 8-12 1823-1835 Masonic Years 37-62, 611, 617, 623, 627 1840-1861 Masonic Years 63-77 -

Historical Sites of the Fauquier County Parks and Recreation Department

Historical Sites of the Fauquier County Parks and Recreation Department Germantown Germantown was Fauquier County’s first permanent settlement, established in 1718 by Germans brought to the Rappahannock River valley by then Lt. Governor Alexander Spotswood in the early 1700’s to excavate iron ore found on his property. Once their terms of service ended, they moved from his settlement along the Rapidan River to land along Licking Run. Many of the family names, such as Fishback, Rector, Kemper, and Hitt, survive in the County today. In 1718, a deed was signed by these early families granting them land along Licking Run. The lots were divided among 19 different families, with the 20th lot being left open for a church and parsonage. Each lot was situated such that the Licking Run would run through each property at some point. The modern-day boundaries of this settlement are Meetze Road along the northeast and Germantown Road along the southwest. Until the American Revolution, these pioneers made their living growing and selling tobacco. As the economy of the country changed, the Germantown families soon turned to growing corn and wheat and raising livestock. In 1985, the United States Soil Conservation Service dammed up Licking Run and created Fauquier County’s largest body of water, Germantown Lake. Along this lake in 1987 C. M. Crockett Park was created, named for Charlie Mitchell Crockett who donated money to purchase the land needed for the park. Crockett’s wife was a descendent of the original Weaver family who had settled in Germantown. More can be learned about early German settlements at www.germanna.org/history.html.