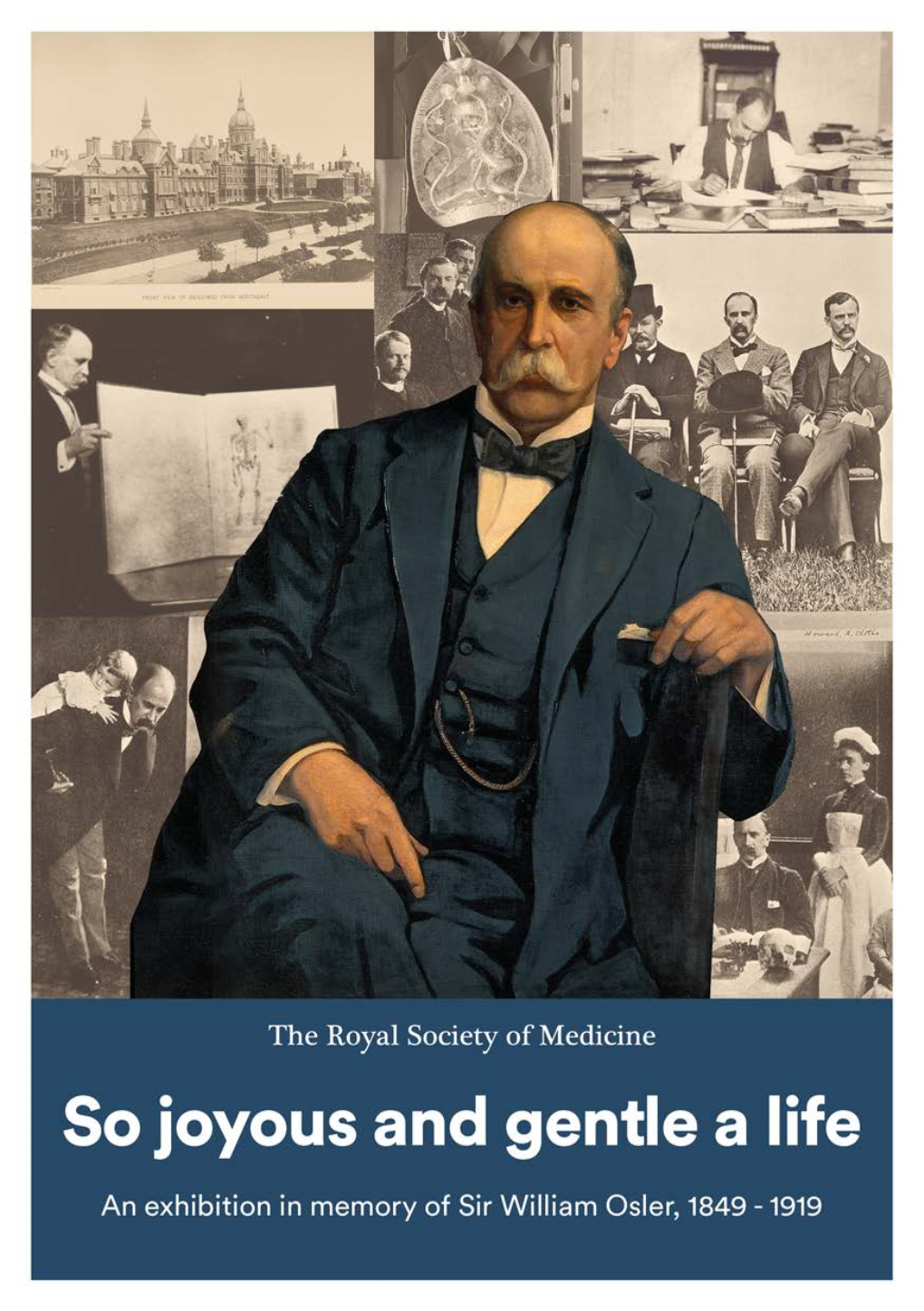

Download the Exhibition Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Newly Purchased Letter T

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The George Eliot Review English, Department of 2-23-1987 A Newly Purchased Letter T. Clifford Allbutt Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Allbutt, T. Clifford, "A Newly Purchased Letter" (1987). The George Eliot Review. 62. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger/62 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George Eliot Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A NEWLY PURCHASED LETTER The following letter has recently been purchased by Nuneaton Museum and Art Gallery ~nd its pub I ication here (as far as we are aware, for the first time) is with the Curator's kind permission. Unfortunately, no year is shown with the date, neither is the correspondent addressed in any other way than by 'My dear Sir', so it has been impossible to discover to whom it was written. All one can say is that it was penned some time between 1890 (the date of publ ication of Oscar Browning's Life of George El iot) and 1925 when Sir Thomas Clifford Allbutt, the writer of the letter, died - a very long span! T. Clifford Allbutt (1836-1925) met George Eliot in 1868. In 1864 he had been appointed physician to. the Leeds General Infi rmary. and George El iot and Lewes spent two days looking around the new hospital with him. -

“MIDDLEMARCH” and the PHYSICIAN (“MIDDLEMARCH” and SIR WILLIAM OSLER) by H

“MIDDLEMARCH” AND THE PHYSICIAN (“MIDDLEMARCH” AND SIR WILLIAM OSLER) By H. A. DEROW, M.D. BOSTON, MASS. “ A SK the opinion of a dozen medical men There are few things better worth the pains / upon the novel in which the doctor in a provincial town like this. A fine fever L \\ is best described, and the majority hospital in addition to the old infirmary might / \\ will say ‘Middlemarch.’” be the nucleus of a medical school here, when we Sir William Osler. once get our medical reforms; and what would George Eliot’s chief object in “Middle do more for medical education than the spread of such schools over the country? march” was to show that “There is no creature whose inward feeling is so strong The extent of the scientific knowledge of that it is not greatly determined by what Lydgate’s colleagues in Middlemarch (the lies outside it, and in obedience to this law, time of the novel is about 1830), as expressed character grows or decays.” Lydgate, the by him, is indicated by the following: physician, is the central figure of special As to the higher questions which determine interest whose career is emblazoned with the starting point of a diagnosis—as to the a great moral for the medical profession. philosophy of medical evidence—any glimmer Settling in Middlemarch, a provincial ing of these can only come from a scientific town of England, Lydgate decided to be a culture of which country practitioners have good Middlemarch doctor and by that usually no more notion than the man in the moon. -

HYG Volume 15 Issue 4 Cover and Back Matter

THE CAMBRIDGE PUBLIC HEALTH SERIES Under the Editorship of G. S. GRAHAM-SMITH, M.D., AND J. E. PURVIS, M.A. Occupations from the Social, Hygienic, and Medical Points of View. By Sir THOMAS OLIVER, M.A., M.D., LL.D., D.Sc, F.R.C.P., Professor of the Principles and Practice of Medicine, University of Durham. Demy 8vo. 6s. net. The Chemical Examination of Water, Sewage, Foods and other Substances. By J. E. PURVIS, M.A., University Lecturer in Chemistry and Physics as applied to Hygiene and Public Health, Cambridge, and T. R. HODGSON, M.A., Public Analyst for the County Boroughs of Blackpool and Wallasey. Demy 8vo. 9s. net. The Bacteriological Examination of Food and Water. By WILLIAM G. SAVAGE, B.SC, M.D., D.P.H., County Medical Officer of Health, Somerset. Demy 8vo. With 16 illustrations. 7s. Qd. net. Sewage Purification and Disposal. By G. BERTRAM KERSHAW, M.Inst.C.E., Consulting Engineer, Engineer to the Royal Commission on Sewage Disposal. Demy 8vo. With 4 tables and 56 text-figures and plans. 12s. net. Post-mortem Metfeods. By J. MARTIN BEATTIE, M.A., M.D., Professor of Bacteriology, University of Liverpool. Demy 8vo. With 8 plates and 3 text-figures. 10s. Qd. net. Isolation Hospitals. By H. FRANKLIN PARSONS, M.D., D.P.H., formerly First Assistant Medical Officer of the Local Government Board. Demy 8vo. With 55 text-figures. 12s. Qd. net. Infant Mortality. By HUGH T. ASHBY, B.A., M.D., B.C. (Camb)., M.R.C.P. (London). Demy 8vo. With 9 illustrations. -

Medical Diary for the Ensuing Week

1596 RONTGEN SOCIETY, Institution of Electrical Engineers, Victoria Embankment, W.C. for TUESDAY.-8.15 P.M., Papers : Dr. Hampson, Prof. W. G. Duffield, Medical Diary the ensuing Week. and Mr. T. Murray Sterilisation of Milk by Electrified Gas. Mr. C. E. S. Phillips will exhibit and describe Some New SOCIETIES. Radium-emanation Applicators. ROYAL SOCIETY, Burlington House, London, W. NOMTH-EAST LONDON CLINICAL SOCIETY, Prince of Wales’s Tottenham. N. THURSDAY.-Sir Francis Darwin : (1) On a Method of Studying Hospital, Transpiration ; (2) The Effect of Light on the Transpiration of THURSDAY.-4.15 P.M., Clinical Meeting. Leaves.-Prof. J. B. Farmer and Mr. L. Digby : On Dimensions of Chromosomes considered in Relation to Phylogeny.-Mr. CHILD STUDY SOCIETY, LONDON, Royal Sanitary Institute, 90, J. H. Mummery: The Process of Calcification in Enamel and Buckingham Palace-road, S.W. Dentine (communicated by Prof. J. Symington).-Mr. A. THURSDAY.-7.30 P.M., Mr. P. B. Ballard: Left-Handedness. Compton : The Optimum Temperature of Salicin Hydrolysis by Enzyme Action is Independent of the Concentrationa of Sub- WEST LONDON MEDICO CHIRURGICAL SOCIETY, West London strate and Enzyme (communicated by Sir J. It. Bradford, Hospital, Hammersmith-road, W. secretary to the Royal Society).-Mr. C. F. U. Meek: The Ratio FRIDAY.-8 P.M., Cases will be shown. 8.30 P.M., Paper:—Mr. Between Spindle Lengths in the Spermatocyte Metaphases of J. E. R. McDonagh : The Biology of Syphilis (illustrated by Heliae Pomatia (communicated by Sir W. T. Thiselton-Dyer).- lantern slides). Followed by a discussion. Dr. A. P. -

July 2019 Medicine’S Lunar Legacies • René T

OslerianaA Medical Humanities Journal-Magazine Volume 1 • July 2019 Medicine’s Lunar Legacies • René T. H. Laennec Walter R. Bett • Leonardo da Vinci OslerianaA Medical Humanities Journal-Magazine Editor-in-Chief Nadeem Toodayan MBBS Associate Editor Zaheer Toodayan MBBS Corrigendum: As indicated in the introductory piece to this journal and in footnotes to their respective articles, both editors are Basic Physician Trainees and therefore registered members of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP). In the initial printing of this volume (on this inner cover and on page 5) the postnominal of ‘MRACP’ was used to refer to the editors’ membership status. This postnominal was first applied to the Edi- tor-in-Chief in formal correspondence from The Osler Club of London. Subsequent discussions with the RACP have confirmed that the postnominal is not formally endorsed by the College for trainee members and so it has been removed in this digital edition. Osleriana – Volume 1 Published July 2019 © The William Osler Society of Australia & New Zealand (WOSANZ) e-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, print, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of WOSANZ or the individual author(s). Permission to reproduce any copyrighted images used in this publication must be obtained from the appropriate rightsholder(s). Please contact WOSANZ for further information as required. Privately printed in Brisbane, Queensland, by Clark & Mackay Printers. Journal concept and WOSANZ logo by Nadeem Toodayan. Journal design and layout by Zaheer Toodayan. -

Ideas About Illness and Healing in the Lisle Letters

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1990 "If I Had My Health ": Ideas about Illness and Healing in the Lisle Letters Margaret T. Mitchell College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Mitchell, Margaret T., ""If I Had My Health ": Ideas about Illness and Healing in the Lisle Letters" (1990). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625621. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-2fya-hv67 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "IF I HAD MY HEALTH...": IDEAS ABOUT ILLNESS AND HEALING IN THE LISLE LETTERS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Meg Mitchell 1990 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts 1KAjuy 'lAj/rfoXvilff.____ Q Author Approved, December 1990 Maryann Brink Dale Hoak Ja|nes McCord ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT..................................................iv CHAPTER I ............................................... -

Touch-Pieces and the King's Evil1

THE SOVEREIGN REMEDY: TOUCH-PIECES AND THE KING'S EVIL1 NOEL WOOLF THE study of Touch-Pieces forms a very small corner of numismatics. Excluding die variations there are a bare dozen types known; and of these one is known only by two examples. The basic research was done more than half a century ago: in England by Miss Helen Farquhar on the numismatic aspects, and by Dr. Raymond Crawfurd on the medical and liturgical; and in France, with a wider historical, philosophical, and metaphysical approach, by Professor Marc Bloch. It is only within recent years that Professor Bloch's work has been available in English. A great deal of the information herein obviously derives from these three sources, and much of it is a distillation of their observations. Miss Farquhar's and Dr. Crawfurd's researches were of course complementary, and perhaps it was because they were both so well and so thoroughly done that so little has been written on these related matters since. But fifty or more years later viewpoints and perspectives have changed and there may even be new scraps of evidence. For the sake of clarity the term 'Touch-Piece' has been reserved for those medalets made between the Restoration of Charles II and the death of his great-nephew Henry, Cardinal Duke of York, in 1807. They were designed solely for use in Touching cere- monies and had no monetary value. The earlier pieces used in a similar manner are referred to by their monetary name 'Angels'. They are all of them, of course, classed as 'Healing Pieces'. -

Osler Library Newsletter

OSLER LIBRARY NEWSLETTER McGILL UNIVERSITY, MONTREAL, CANADA No. 47 - October 1984 A NARRATIVE OF OSLER'S LAST ILLNESS EAR THEENDof his Life of Sir William 5. xii. '19 When I telephoned after lunch yesterday Sir Wm. heard Osler, Harvey Cushing mentions T. about it and said he wished me to be here. I came down on the 4.45 Archibald Malloch's arrival at Oxford «bringing Reord syringe & needles with me" and Dr. Gibson soon early in December of 1919 and the notes came & told me the white count was 27,000 & agreed that !a\ that Malloch kept of Osler's last illness. «the" chest should be needled. (I had written on 1st to him that W.O. suspected a loculated collection & said 'I imagine it would The notes resurfaced this summer when comfort him to have his chest needled in a couple of places' - his they came to the Osler Library with a temp. from being normal had risen on 30th Nov. to 101°. [)] Sir group of Malloch's books and Thos. Horder came at 8.22 & I met him. After he had dinner Drs manuscripts, the gift dfhis son, Professor A.E. Malloch. The notes Collier & Gibson came in and we discussed the case & then he are here published for thefirst time. Their importance lies in being went up & examined W.O. then we all talked it over in the sitting- an eye-witness account of the final stage of Osler's life. room. He thought there possible [sic] was a focus (an abscess) in the rt. 1.1. -

Childhood Asthma and Beyond

Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine CHILDHOOD ASTHMA AND BEYOND A Witness Seminar held at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London, on 4 April 2000 Volume 11 – November 2001 CONTENTS Introduction Mark Jackson i Witness Seminars: Meetings and publications;Acknowledgements E M Tansey and L A Reynolds vi Transcript Edited by L A Reynolds and E M Tansey 1 Index 67 INTRODUCTION One Sunday morning earlier this year, I was offered a potent and disturbing reminder of current trends in childhood asthma. Our one-year-old son, Conall, had developed a loud expiratory wheeze and persistent nocturnal cough following a series of debilitating upper respiratory tract infections and, perhaps significantly, coinciding with the extremely high pollen counts recorded that month. We had attempted to relieve the symptoms with a salbutamol inhaler delivered through a spacer and mask but to no effect. That morning, he began exhibiting signs of severe respiratory distress and I took him to the accident and emergency department in the small local hospital. He was given nebulized salbutamol which immediately eased both his (and my) distress and the wheeze, he was prescribed a short course of oral steroids and a follow- up steroid inhaler, and we were advised to see our GP later that week. Of course, our experience was by no means unusual. We all know families where young children suffer recurrent episodes of wheezing and nocturnal coughing, and where the use of both β-agonist and steroid inhalers is commonplace. When we lived in Manchester, where our older son, Riordan, first developed symptoms of asthma three or four years ago, our GP was insistent that the number of wheezy children seen in her surgery had increased dramatically over the previous ten years, particularly in those areas of Manchester close to major roads. -

Shaping the Future Annual Report 2017 RCP Annual Report and Accounts 2017

Shaping the future Annual report 2017 RCP annual report and accounts 2017 About the RCP The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is a professional membership body for physicians, with over 34,000 members and fellows around the globe working in hospitals and communities across 30 medical specialties. Physicians diagnose and treat illness, and promote good health. They care for millions of medical patients with a broad range of conditions, from asthma and diabetes to stroke and yellow fever. Our vision is the best possible health and healthcare for everyone. Everything that we do at the RCP aims to improve patient care and reduce illness. Our work is patient centred and clinically led. We drive improvement in the diagnosis of disease, the care of individual patients and the health of the whole population, both in the UK and across the globe. We also work to ensure that physicians are educated and trained to provide high-quality care. 2 RCP annual report and accounts 2017 Contents > Foreword 4 > Report of trustees 5 > Improving care for patients 6 > Developing physicians throughout their careers 7 > Leading and supporting our members 8 > Shaping the future of health and healthcare 10 > Investing in our future, building on our heritage 12 > Our plans for 2018 18 > RCP boards, committees and lists 24 > Financial powers and policies 28 > Structure, governance and management 31 > Statement of trustees’ responsibilities 33 > Treasurer’s annual report 35 > Independent auditor’s report to the trustees of the RCP 38 > Consolidated statement of financial activities 40 > Consolidated and RCP balance sheets 41 > Consolidated statement of cash flow 42 > Notes to the consolidated statement of cash flow 43 > Notes to the financial statements 44 3 RCP annual report and accounts 2017 Foreword The pressures on the NHS were very visible in the media throughout 2017. -

Sydenham's Influence Abroad*

SYDENHAM'S INFLUENCE ABROAD* by F. N. L. POYNTER A DOZEN of these Sydenham Memorial Lectures have already been given and several of them have made a substantial contribution to our knowledge of Sydenham and his times. It was in one of these lectures that Dr. Dewhurst first gave us in summary form the new biography of Sydenham, based on newly accessible sources in the Bodleian Library, which was later published in greatly expanded form in the Weilcome Historical Monograph series.1 It was in another that the late Dr. Richard Trail gave us a detailed study of Sydenham's influence on English medicine. Dr. Hugh Sinclair, an acknowledged authority on the work and writing of the great Dutch clinician, Herman Boerhaave, spoke to us of Sydenham's influence on his ideas, but un- fortunately did not publish his lecture. Neither of the standard biographies of Sydenham, the first by J. F. Payne2 and the modern work by Dewhurst, says very much about Sydenham's influence outside England. This is an obvious gap in our historical knowledge which I shall try to fill, at least in outline, in this lecture. Clearly, it is not at all satisfying for a historian simply to declare, as many have, that Sydenham's influence spread rapidly throughout Europe and that his fame has persisted. It is our duty to probe rather more deeply and to inquire how and in what form this influence was spread and how the subsequent development of medicine was affected. In our search we shall follow three particular themes which were held to be the most important in his work among those whom he influenced. -

Medico-Chiruirgical Transactions

MEDICO-CHIRUIRGICAL TRANSACTIONS PUBLISHED BY THE ROYAL MEDICAL AND CHIRURGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON VOLUME THE EIGHTY-NINTH (SECOND SERIES, VOLUME THE SEVENTY-FIRST) LONDON LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO. (FOR THE ROYAL MEDICAL AND CHIRURGICAL SOCiETY OF LONDON) PATERNOSTER ROW 1906 Issued from the Society's House ait 20, Hanover Square, W. September, 1906. PRINTED BY ADLARD AND SON, BARTHOLOMEW CLOSE, E.C. ROYAL MEDICAL AND CHIRURGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON PATRON THE KING OFFICERS AND COUNCIL ELECTED MARCH 1, 1906 rtsih lx J. WARRINGTON HAWARD. THOMAS BUZZARD, M.D. VICE-PRESIDENTS JOSEPHHERBERTFRANKWILLIAMPAYNE,PAGE,M.D.M.C. W. HARRISON CRIPPS SIR WILLIAM SELBY CHURCH, BART., K.C.B., M.D. HO.TREASURERSfHALFRED PEARCE GOULD, M.S. C.M.G., M.D. HON.SECRETARIIE8S(HOWARDHONSCREARESSTEPHEN HENRYPAGET TOOTH, MooRE, M.D. HONLBRAIARfNoRtMANHRICKMAN JOHN GODLEE, M.S. (THEODORE DYKE ACLAND, M.D). EDWIN CLIFFORD BEALE, M.B. SIDNEY H. C. MARTIN, M.D., F.R.S. OTHER | GEORGE OGILVIE, M.B.M.D. MEMBERS O WILLIAM1 PASTEUR, O JOHN BLAND-SUTTON COUNCIMBCOUNIL IANDREW CLARK CLINTON THOMAs DENT WALTER H. H. JESSOP HENRY ROXBURGH FULLER, M.D. THE ABOVE FORM THE COUNCIL SECRETARY AND CONSULTING LIBRARIAN J. Y. W. MAC ALISTER, F.S.A. FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY APPOINTED BY THE COUNCIL AS REFEREES OF PAPERS FOR THE SESSION OF 1906-7 C. A. BALLANCE, M.S. G. H. MAKINS, C.B. C. E. BEEVOR, M.D. SIR PATRICK MANSON, K.C.M.G., ARTHUR E. J. BARKER M.D., F.R.S. SIR WILLIAMi H. BENNETT,K.C.V.O. JOHN HAMMOND MORGAN, C.V.O.