Open PDF 210KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LGBT+ Conservatives Annual Report 2020.Pdf

LGBT+ CONSERVATIVES TEAM April 2019 - July 20201 OFFICERS CHAIRMAN - Colm Howard-Lloyd DEPUTY CHAIRMAN - John Cope HONORARY SECRETARY - Niall McDougall HONORARY TREASURER - Cllr. Sean Anstee CBE VICE-CHAIRMAN CANDIDATES’ FUND - Cllr. Scott Seaman-Digby VICE-CHAIRMAN COMMUNICATIONS - Elena Bunbury (resigned Dec 2019) VICE-CHAIRMAN EVENTS - Richard Salt MEMBERSHIP OFFICER - Ben Joce STUDENT OFFICER - Jason Birt (resigned Sept 2019) GENERAL COUNCIL Cllr. Andrew Jarvie Barry Flux David Findlay Dolly Theis Cllr. Joe Porter Owen Meredith Sue Pascoe Xavier White REGIONAL COORDINATORS EAST MIDLANDS - David Findlay EAST OF ENGLAND - Thomas Smith LONDON - Charley Jarrett NORTH EAST - Barry Flux SCOTLAND - Andrew Jarvie WALES - Mark Brown WEST MIDLANDS - John Gardiner YORKSHIRE AND THE HUMBER - Cllr. Jacob Birch CHAIRMAN’S REPORT After a decade with LGBT+ Conservatives, more than half of them in the chair, it’s time to hand-on the baton I’m not disappearing completely. One of my proudest achievements here has been the LGBT+ Conservatives Candidates’ Fund, which has supported so many people into parliament and raised tens of thousands of pounds. As the fund matures it is moving into a new governance structure, and I hope to play a role in that future. I am thrilled to be succeeded by Elena Bunbury. I know that she will bring new energy to the organisation, and I hope it will continue to thrive under her leadership. I am so grateful to everyone who has supported me on this journey. In particular Emma Warman, Matthew Green and John Cope who have provided wise counsel as Deputy Chairman. To Sean Anstee who has transformed the finances of the organisation. -

Political Affairs Digest a Daily Summary of Political Events Affecting the Jewish Community

24 January 2020 Issue 1,938 Political Affairs Digest A daily summary of political events affecting the Jewish Community Contents Home Affairs Relevant Legislation Holocaust Consultations Home Affairs Westminster Hall Debate Assisted Dying Law col 186WH Christine Jardine (Liberal Democrat): … The current law in this country simply is not working. I hope that we can begin to address today the effect of that law on terminally ill people and their loved ones, and on public servants such as doctors, health and social care professionals, police and coroners. … this issue is hugely evocative, can involve issues of faith and puts the medical profession in the most difficult of positions. It is also, of course, the most personal, intimate and ultimate of decisions. … Andrew Selous (Conservative): … Does the hon. Lady agree that we need to be very careful to ensure that old and sick people do not feel a pressure to end their lives, perhaps from their children, who might want to inherit their assets and to whom they may feel they are being a burden? Christine Jardine: … That is why I am so concerned that we should have a very narrow and precise definition if we change the law. … col 187WH Fiona Bruce (Conservative): What is the hon. Lady’s response to the evidence that, in countries where assisted suicide has been made legal, investment in palliative care has fallen? Christine Jardine: … That is something we would have to be aware of, but I believe it is up to us to address it. … col 188WH Rupa Huq (Labour): … I get her point that saying goodbye in an airport is not the best thing for people who choose to go to Switzerland, but at the same time I worry about safeguards. -

View Future Day Orals PDF File 0.11 MB

Published: Monday 28 September 2020 Questions for oral answer on a future day (Future Day Orals) Questions for oral answer on a future day as of Monday 28 September 2020. The order of these questions may be varied in the published call lists. [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Tuesday 29 September Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Grahame Morris (Easington): Whether he plans to prioritise the development and uptake of human-relevant new approach methodologies in the forthcoming UK research and development roadmap. (906764) Craig Williams (Montgomeryshire): What steps his Department is taking to support businesses during the covid-19 outbreak. (906765) David Mundell (Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale and Tweeddale): What steps his Department is taking to support the Department for International Trade in removing tariffs on Scotch malt whisky. (906766) Neil Parish (Tiverton and Honiton): What steps his Department is taking to help businesses reduce emissions. (906767) Miriam Cates (Penistone and Stocksbridge): What steps his Department is taking to support manufacturing. (906768) Sally-Ann Hart (Hastings and Rye): What steps his Department is taking to support the marine energy sector. (906769) Joy Morrissey (Beaconsfield): What steps his Department is taking to support an environmentally sustainable economic recovery in the automotive sector. (906770) Mrs Emma Lewell-Buck (South Shields): What recent discussions he has had with representatives from those business sectors most affected by the covid-19 outbreak. (906771) 2 Monday 28 September 2020 QUESTIONS FOR ORAL ANSWER ON A FUTURE DAY Neale Hanvey (Kirkcaldy and Cowdenbeath): What recent discussions he has had with (a) Cabinet colleagues and (b) the Scottish Government on the economic effect on businesses of the UK Internal Market Bill. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

Daily Report Thursday, 20 May 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 20 May 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 20 May 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:30 P.M., 20 May 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 5 Government Departments: ATTORNEY GENERAL 5 Cost Effectiveness 12 [Subject Heading to be India: Visits Abroad 12 Assigned] 5 Regional Planning and BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Development: Civil Servants 13 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 5 Third Sector 13 Amazon: Delivery Services 5 CHURCH COMMISSIONERS 14 Animal Experiments 6 St Paul's Cathedral 14 Hospitality Industry: DEFENCE 15 Recruitment 7 Armoured Fighting Vehicles: Nuclear Power: Finance 7 Procurement 15 Post Office Horizon IT Inquiry 8 Challenger Tanks: Depleted Post Office Horizon IT Inquiry: Uranium 15 Witnesses 8 Cybercrime 15 CABINET OFFICE 9 HMS Queen Elizabeth: Joint 11 Downing Street: Repairs Strike Fighter Aircraft 16 and Maintenance 9 RAF Valley 16 Animal Products: UK Trade Terrorism: Weapons of Mass with EU 9 Destruction 17 Census: Gender Recognition 9 DIGITAL, CULTURE, MEDIA AND Constitution, Democracy and SPORT 18 Rights Commission 10 Arts Council: Music 18 Coronavirus: Vaccination 10 Culture, Practices and Ethics Drugs: Northern Ireland 11 of the Press Inquiry 18 Elections: Fraud 11 Digital Markets Unit: Staff 19 Electronic Warfare: Public Sector 12 Dormant Assets Scheme: FOREIGN, COMMONWEALTH National Lottery Community -

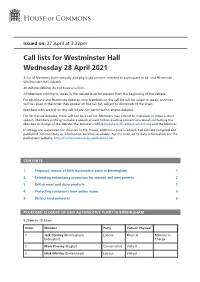

View Call Lists: Westminster Hall PDF File 0.05 MB

Issued on: 27 April at 3.32pm Call lists for Westminster Hall Wednesday 28 April 2021 A list of Members, both virtually and physically present, selected to participate in 60- and 90-minute Westminster Hall debates. 30-minute debates do not have a call list. All Members wishing to speak in the debate must be present from the beginning of the debate. For 60-minute and 90-minute debates, only Members on the call list will be called to speak, and they will be called in the order they appear on the call list, subject to discretion of the Chair. Members who are not on the call list are not permitted to attend debates. For 30-minute debates, there will not be a call list. Members may attend to intervene or make a short speech. Members wishing to make a speech should follow existing conventions about contacting the Member in charge of the debate, the Speaker’s Office [email protected]( ) and the Minister. If sittings are suspended for divisions in the House, additional time is added. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to-date information see the parliament website: https://commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ CONTENTS 1. Proposed closure of GKN Automotive plant in Birmingham 1 2. Extending redundancy protection for women and new parents 2 3. British meat and dairy products 2 4. Protecting consumers from online scams 3 5. District heat networks 3 PROPOSED CLOSURE OF GKN AUTOMOTIVE PLANT IN BIRMINGHAM 9.25am to 10.55am Order Member Party Virtual/ Physical 1 Jack Dromey (Birmingham, -

Daily Report Tuesday, 23 March 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Tuesday, 23 March 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 23 March 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:57 P.M., 23 March 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 7 Railways: Coal 19 ATTORNEY GENERAL 7 Renewable Energy 19 Slavery 7 Research 20 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Retail Trade: Coronavirus 20 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 7 STEP Programme 20 ACAS: Coronavirus 7 UK Research and Innovation: Biofuels 8 Overseas Aid 21 Chemicals: Exports 8 CABINET OFFICE 22 Clothing: Manufacturing Blood: Contamination 22 Industries 9 Cabinet Office: Written Committee on Climate Change 13 Questions 23 Conditions of Employment 14 Census: Forms 23 Courier Services: Northern Census: Telephone Services 23 Ireland 14 Coronavirus: Vaccination 24 Department for Business, Elections: Proof of Identity 24 Energy and Industrial Strategy: Honours 15 Immigration: Climate Change 24 Free Zones 16 National Democracy Week 25 Iron and Steel 16 Weddings: Coronavirus 26 Iron and Steel: Carbon DEFENCE 27 Emissions 16 BOWMAN Combat Radio Iron and Steel: Manufacturing System 27 Industries 17 Chinook Helicopters 27 Post Office Horizon IT Inquiry 18 Defence: Procurement 28 Post Office: Miscarriages of Helicopters 28 Justice 18 LE TacCIS Programme 28 Post Offices 19 Military Aircraft: Helicopters 29 Ministry of Defence: Research 29 Languages: GCE A-level and NATO Enlargement 29 GCSE -

Frohe Weinachten Feliz Navidad Joyeux Noël Buon Natale Καλά

Volume 37 Number 3 Success at CoP26 starts at home: Leading by example on Net Zero - Steve Holliday FREng FEI Transport and Heating towards Net Zero – Hydrogen update December 2020 Renewables: leading transitions to a more sustainable energy system – Dr Fatih Birol, IEA Launch of PGES 40th Anniversary Inquiry ENERGY FOCUS Frohe Weinachten καλά Χριστούγεννα Feliz Navidad Bożego Narodzenia Joyeux Noël Vrolijk kerstfeest Buon Natale Wesołych świąt Veselé Vianoce Veselé Vánoce Crăciun fericit Glædelig jul Vesel božič Feliz Natal God Jul This is not an official publication of the House of Commons or the House of Lords. It has not been approved by either House or its committees. All-Party Parliamentary Groups are informal groups of Members of both Houses with a common interest in particular issues. The views expressed in Energy Focus are those of the individual organisations and contributors Back to Contents and doBack not necessarily to Contents represent the views held by the All-Party Parlia- mentary Group for Energy Studies. The journal of The All-Party Parliamentary Group for Energy Studies Established in 1980, the Parliamentary Group for Energy Studies remains the only All-Party Parliamentary Group representing the entire energy industry. PGES aims to advise the Government of the day of the energy issues of the day. The Group’s membership is comprised of over 100 parliamentarians, 100 associate bodies from the private, public and charity sectors and a range of individual members. Published three times a year, Energy Focus records the Group’s activities, tracks key energy and environmental developments through parliament, presents articles from leading industry contributors and provides insight into the views and interests of both parliamentarians and officials. -

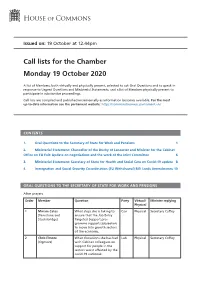

View Call Lists

Issued on: 19 October at 12.44pm Call lists for the Chamber Monday 19 October 2020 A list of Members, both virtually and physically present, selected to ask Oral Questions and to speak in response to Urgent Questions and Ministerial Statements; and a list of Members physically present to participate in substantive proceedings. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to-date information see the parliament website: https://commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ CONTENTS 1. Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions 1 2. Ministerial Statement: Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office on EU Exit: Update on negotiations and the work of the Joint Committee 6 3. Ministerial Statement: Secretary of State for Health and Social Care on Covid-19 update 8 4. Immigration and Social Security Co-ordination (EU Withdrawal) Bill: Lords Amendments 10 ORAL QUESTIONS TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS After prayers Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister replying Physical 1 Miriam Cates What steps she is taking to Con Physical Secretary Coffey (Penistone and ensure that the Job Entry Stocksbridge) Targeted Support pro- gramme supports jobseekers to move into growth sectors of the economy. 2 Chris Elmore What discussions she has had Lab Physical Secretary Coffey (Ogmore) with Cabinet colleagues on support for people in the sectors worst affected by the covid-19 outbreak. 2 Call lists for the Chamber Monday 19 October 2020 Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister replying Physical 3 Neil Gray (Airdrie and Supplementary SNP Virtual Secretary Coffey Shotts) 4 Alison McGovern What recent assessment she Lab Physical Minister Quince (Wirral South) has made of the effect of the covid-19 outbreak on levels of child poverty. -

Elliot Colburn MP Vice-Chair of the APPG on HIV and AIDS House of Commons London SW1A 0AA

Elliot Colburn MP Vice-Chair of the APPG on HIV and AIDS House of Commons London SW1A 0AA [email protected] 8th April 2021 Wendy Morton MP Parliamentary Under Secretary of State Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office King Charles Street, London SW1A 2AH Dear Minister, We are writing on behalf of the All Party Parliamentary Group on HIV & AIDS, and UK civil society organisations, to request your attendance at the upcoming UN High Level Meeting on Ending AIDS. With the UK’s support and leadership, incredible progress has been made in the global response to HIV. However, even before the covid crisis, global funding and political prioritisation for HIV was stagnating despite an increasing financial need and the situation has only deteriorated thanks to the covid crisis. We believe that at this pivotal time, Minister-level attendance is critical to send a strong signal of the UK’s ongoing commitment and leadership of the global HIV response. While sadly nearly 2.2 million people have already died worldwide from COVID-19, approximately 2.5 million people still die every year from AIDS, TB and malaria even with the enormous progress of the past two decades. COVID-19 threatens to reverse that progress and increase deaths, with nearly 75% of lifesaving HIV, TB and malaria programs disrupted. The rate of HIV infections remains stubbornly high, with 1.7 million people acquiring HIV in 2019. Shockingly, AIDS remains the number one killer of women of reproductive age. These are all preventable deaths. It is imperative that we, as the global community, scale up our efforts now to fight AIDS, or risk undoing decades of hard-won progress and a resurgence of the epidemic at even higher proportions. -

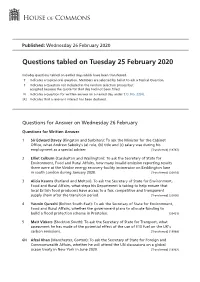

Questions Tabled on Tue 25 Feb 2020

Published: Wednesday 26 February 2020 Questions tabled on Tuesday 25 February 2020 Includes questions tabled on earlier days which have been transferred. T Indicates a topical oral question. Members are selected by ballot to ask a Topical Question. † Indicates a Question not included in the random selection process but accepted because the quota for that day had not been filled. N Indicates a question for written answer on a named day under S.O. No. 22(4). [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Wednesday 26 February Questions for Written Answer 1 Sir Edward Davey (Kingston and Surbiton): To ask the Minister for the Cabinet Office, what Andrew Sabisky's (a) role, (b) title and (c) salary was during his employment as a special adviser. [Transferred] (19747) 2 Elliot Colburn (Carshalton and Wallington): To ask the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, how many invalid emission reporting results there were at the Viridor energy recovery facility incinerator on Beddington lane in south London during January 2020. [Transferred] (20018) 3 Alicia Kearns (Rutland and Melton): To ask the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, what steps his Department is taking to help ensure that local British food producers have access to a fair, competitive and transparent supply chain after the transition period. [Transferred] (20000) 4 Yasmin Qureshi (Bolton South East): To ask the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, whether the government plans to allocate funding to build a flood protection scheme in Prestolee. (20431) 5 Matt Vickers (Stockton South): To ask the Secretary of State for Transport, what assessment he has made of the potential effect of the use of E10 fuel on the UK's carbon emissions. -

Parliamentary Monitoring March 2021

ADEPT: Parliamentary monitoring March 2021 This document is tailored to provide a monthly overview of key activity, debates, questions, reports, PMQs, speeches and bills relevant to the Association of Directors of Environment, Economy, Planning and Transport. Key dates 03 March: Budget 25 March: Easter recess 13 April: House returns 11 May: Queen’s Speech – State Opening of Parliament 27 May: Whitsun recess (tbc) 7 June 2021: House returns (tbc) Devolution deals Date Type Organisation Notes 09/03/21 Report Devolution Levelling-up Devo. The role of national APPG government in making a success of devolution in England. Here 16/03/21 Report MHCLG Devolution annual report 2019 to 2020 The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government has published its devolution annual report 2019 to 2020 that brings together information about devolution agreements reached or implemented between government and areas between 1 April 2019 and 31 March 2020. The full report can be accessed here Digital – Broadband & mobile Date Type Organisation Notes 19/03/21 Press release DCMS Government launches new £5bn ‘Project Gigabit’. More than one million hard to reach homes and businesses will have next generation gigabit broadband built to them in the first phase of a £5 billion government infrastructure project. Here 22/03/21 Written DCMS Project Gigabit - UIN HCWS866 statement Matt Warman, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Digital Infrastructure: Gigabit broadband is being rolled out rapidly, from one in ten households in 2019 to almost two in five today. The UK is on track for one of the fastest rollouts in Europe and for half the country to have access to gigabit speeds by the end of this year.