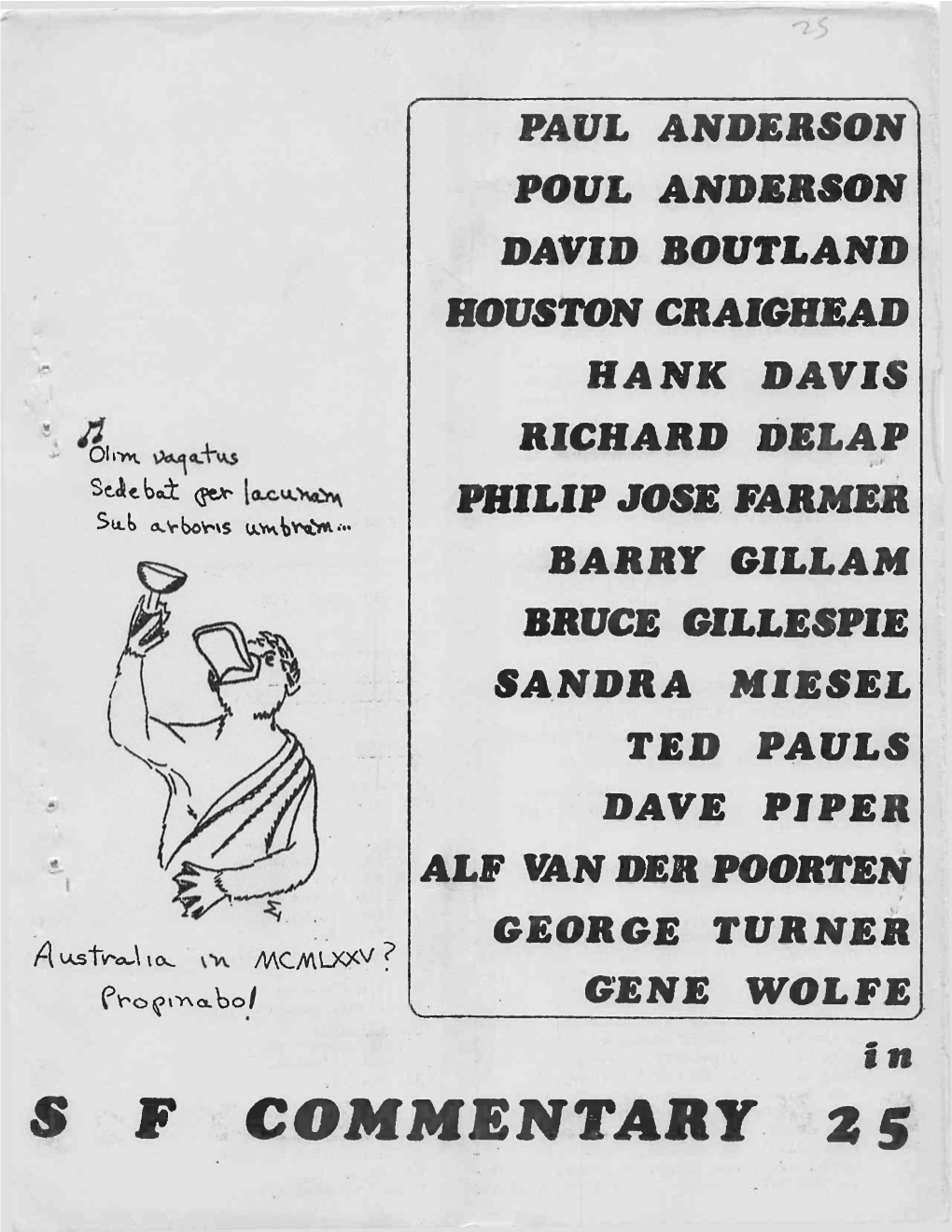

SF Commentary 25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian SF News 28

NUMBER 28 registered by AUSTRALIA post #vbg2791 95C Volume 4 Number 2 March 1982 COW & counts PUBLISH 3 H£W ttOVttS CORY § COLLINS have published three new novels in their VOID series. RYN by Jack Wodhams, LANCES OF NENGESDUL by Keith Taylor and SAPPHIRE IN THIS ISSUE: ROAD by Wynne Whiteford. The recommended retail price on each is $4.95 Distribution is again a dilemna for them and a^ter problems with some DITMAR AND NEBULA AWARD NOMINATIONS, FRANK HERBERT of the larger paperback distributors, it seems likely that these titles TO WRITE FIFTH DUNE BOOK, ROBERT SILVERBERG TO DO will be handled by ALLBOOKS. Carey Handfield has just opened an office in Melbourne for ALLBOOKS and will of course be handling all their THIRD MAJIPOOR BOOK, "FRIDAY" - A NEW ROBERT agencies along with NORSTRILIA PRESS publications. HEINLEIN NOVEL DUE OUT IN JUNE, AN APPRECIATION OF TSCHA1CON GOH JACK VANCE BY A.BERTRAM CHANDLER, GEORGE TURNER INTERVIEWED, Philip K. Dick Dies BUG JACK BARRON TO BE FILMED, PLUS MORE NEWS, REVIEWS, LISTS AND LETTERS. February 18th; he developed pneumonia and a collapsed lung, and had a second stroke on February 24th, which put him into a A. BERTRAM CHANDLER deep coma and he was placed on a respir COMPLETES NEW NOVEL ator. There was no brain activity and doctors finally turned off the life A.BERTRAM CHANDLER has completed his support system. alternative Australian history novel, titled KELLY COUNTRY. It is in the hands He had a tremendous influence on the sf of his agents and publishers. GRIMES field, with a cult following in and out of AND THE ODD GODS is a short sold to sf fandom, but with the making of the Cory and Collins and IASFM in the U.S.A. -

SF Commentary 41-42

S F COMMENTARY 41/42 Brian De Palma (dir): GET TO KNOW YOUR RABBIT Bruce Gillespie: I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS (86) . ■ (SFC 40) (96) Philip Dick (13, -18-19, 37, 45, 66, 80-82, 89- Bruce Gillespie (ed): S F COMMENTARY 30/31 (81, 91, 96-98) 95) Philip Dick: AUTOFAC (15) Dian Girard: EAT, DRINK AND BE MERRY (64) Philip Dick: FLOW MY TEARS THE POLICEMAN SAID Victor Gollancz Ltd (9-11, 73) (18-19) Paul Goodman (14). Gordon Dickson: THINGS WHICH ARE CAESAR'S (87) Giles Gordon (9) Thomas Disch (18, 54, 71, 81) John Gordon (75) Thomas Disch: EMANCIPATION (96) Betsey & David Gorman (95) Thomas Disch: THE RIGHT WAY TO FIGURE PLUMBING Granada Publishing (8) (7-8, 11) Gunter Grass: THE TIN DRUM (46) Thomas Disch: 334 (61-64, 71, 74) Thomas Gray: ELEGY WRITTEN IN A COUNTRY CHURCH Thomas Disch: THINGS LOST (87) YARD (19) Thomas Disch: A VACATION ON EARTH (8) Gene Hackman (86) Anatoliy Dneprov: THE ISLAND OF CRABS (15) Joe Haldeman: HERO (87) Stanley Donen (dir): SINGING IN THE RAIN (84- Joe Haldeman: POWER COMPLEX (87) 85) Knut Hamsun: MYSTERIES (83) John Donne (78) Carey Handfield (3, 8) Gardner Dozois: THE LAST DAY OF JULY (89) Lee Harding: FALLEN SPACEMAN (11) Gardner Dozois: A SPECIAL KIND OF MORNING (95- Lee Harding (ed): SPACE AGE NEWSLETTER (11) 96) Eric Harries-Harris (7) Eastercon 73 (47-54, 57-60, 82) Harry Harrison: BY THE FALLS (8) EAST LYNNE (80) Harry Harrison: MAKE ROOM! MAKE ROOM! (62) Heinz Edelman & George Dunning (dirs): YELLOW Harry Harrison: ONE STEP FROM EARTH (11) SUBMARINE (85) Harry Harrison & Brian Aldiss (eds): THE -

The Apocalyptic Book List

The Apocalyptic Book List Presented by: The Post Apocalyptic Forge Compiled by: Paul Williams ([email protected]) As with other lists compiled by me, this list contains material that is not strictly apocalyptic or post apocalyptic, but that may contain elements that have that fresh roasted apocalyptic feel. Because I have not read every single title here and have relied on other peoples input, you may on occasion find a title that is not appropriate for the intended genre....please do let me know and I will remove it, just as if you find a title that needs to be added...that is appreciated as well. At the end of the main book list you will find lists for select series of books. Title Author 8.4 Peter Hernon 905 Tom Pane 2011, The Evacuation of Planet Earth G. Cope Schellhorn 2084: The Year of the Liberal David L. Hale 3000 Ad : A New Beginning Jon Fleetwood '48 James Herbert Abyss, The Jere Cunningham Acts of God James BeauSeigneur Adulthood Rites Octavia Butler Adulthood Rites, Vol. 2 Octavia E. Butler Aestival Tide Elizabeth Hand Afrikorps Bill Dolan After Doomsday Poul Anderson After the Blue Russel C. Like After the Bomb Gloria D. Miklowitz After the Dark Max Allan Collins After the Flames Elizabeth Mitchell After the Flood P. C. Jersild After the Plague Jean Ure After the Rain John Bowen After the Zap Michael Armstrong After Things Fell Apart Ron Goulart After Worlds Collide Edwin Balmer, Philip Wylie Aftermath Charles Sheffield Aftermath K. A. Applegate Aftermath John Russell Fearn Aftermath LeVar Burton Aftermath, The Samuel Florman Aftershock Charles Scarborough Afterwar Janet Morris Against a Dark Background Iain M. -

For Fans by Fans: Early Science Fiction Fandom and the Fanzines

FOR FANS BY FANS: EARLY SCIENCE FICTION FANDOM AND THE FANZINES by Rachel Anne Johnson B.A., The University of West Florida, 2012 B.A., Auburn University, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Department of English and World Languages College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities The University of West Florida In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2015 © 2015 Rachel Anne Johnson The thesis of Rachel Anne Johnson is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Baulch, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Earle, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _________________ Gregory Tomso, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _________________ Richard S. Podemski, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank Dr. David Earle for all of his help and guidance during this process. Without his feedback on countless revisions, this thesis would never have been possible. I would also like to thank Dr. David Baulch for his revisions and suggestions. His support helped keep the overwhelming process in perspective. Without the support of my family, I would never have been able to return to school. I thank you all for your unwavering assistance. Thank you for putting up with the stressful weeks when working near deadlines and thank you for understanding when delays -

Judith Merril's Expatriate Narrative, 1968-1972 by Jolene Mccann a Thesis Submi

"The Love Token of a Token Immigrant": Judith Merril's Expatriate Narrative, 1968-1972 by Jolene McCann A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 2006 © Jolene McCann, 2006 Abstract Judith Merril was an internationally acclaimed science fiction (sf) writer and editor who expatriated from the United States to Canada in November 1968 with the core of what would become the Merril Collection of Science Fiction, Speculation and Fantasy in Toronto. Merril chronicled her transition from a nominal American or "token immigrant" to an authentic Canadian immigrant in personal documents and a memoir, Better to Have Loved: the Life of Judith Merril (2002). I argue that Sidonie Smith's travel writing theory, in particular, her notion of the "expatriate narrative" elucidates Merril's transition from a 'token' immigrant to a representative token of the American immigrant community residing in Toronto during the 1960s and 1970s. I further argue that Judith Merril's expatriate narrative links this personal transition to the simultaneous development of her science fiction library from its formation at Rochdale College to its donation by Merril in 1970 as a special branch of the Toronto Public Library (TPL). For twenty-seven years after Merril's expatriation from the United States, the Spaced Out Library cum Merril Collection - her love-token to the city and the universe - moored Merril politically and intellectually in Toronto. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Dianne Newell for introducing me to the Merril Collection and sharing her extensive collection of primary sources on science fiction and copies of Merril's correspondence with me, as well as for making my visit to the Merril Collection at the Library and Archives of Canada, Ottawa possible. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

Tightbeam 305 Part 1

Tightbeam 305 February 2020 Fairy Sword by Angela K. Scott Tightbeam 305 February 2020 The Editors are: George Phillies [email protected] 48 Hancock Hill Drive, Worcester, MA 01609. Jon Swartz [email protected] Art Editors are Angela K. Scott, Jose Sanchez, and Cedar Sanderson. Anime Reviews are courtesy Jessi Silver and her site www.s1e1.com. Ms. Silver writes of her site “S1E1 is primarily an outlet for views and reviews on Japanese animated media, and occasionally video games and other entertainment.” Regular contributors include Declan Finn, Jim McCoy, Pat Patterson, Tamara Wilhite, Chris Nuttall, Tom Feller, and Heath Row. Declan Finn’s web page de- clanfinn.com covers his books, reviews, writing, and more. Jim McCoy’s reviews and more appear at jimbossffreviews.blogspot.com. Pat Patterson’s reviews ap- pear on his blog habakkuk21.blogspot.com and also on Good Reads and Ama- zon.com. Tamara Wilhite’s other essays appear on Liberty Island (libertyislandmag.com). Chris Nuttall’s essays and writings are seen at chrishang- er.wordpress.com and at superversivesf.com. Some contributors have Amazon links for books they review; use them and they get a reward from Amazon. Regular short fiction reviewers Greg Hullender and Eric Wong publish at RocketStackRank.com. Cedar Sanderson’s reviews and other interesting articles appear on her site www.cedarwrites.wordpress.com/ and its culinary extension . Tightbeam is published approximately monthly by the National Fantasy Fan Federation and distributed electronically to the membership. The N3F offers four different memberships. Memberships with The National Fantasy Fan (TNFF) via paper mail are $18; memberships with TNFF via email are $6. -

22 Tightbeam

22 TIGHTBEAM Those multiple points of connection—and favorites—indicate the show’s position of preference in popular culture, and Tennant said he’s consistently surprised by how Doctor Who fandom and awareness has spread internationally—despite its British beginnings. “Doctor Who is part of the cultural furniture in the UK,” he said. “It’s something that’s uniquely British, that Britain is proud of, and that the British are fascinated by.” Now, when Tennant is recognized in public, he can determine how much a fan of the show the person is based on what they say to him. “If someone says, ‘Allons-y!’ chances are they’re a fan,” he said. Most people say something like, “Where’s your Tardis?” or “Aren’t you going to fix that with your sonic screwdriver?” There might be one thing that all fans can agree on. Perhaps—as Tennant quipped—Doctor Who Day, Nov. 23 (which marks the airing of the first episode, “An Unearthly Child”) should be a national holiday. Regardless of what nation—or planet—you call home. Note: For a more in-depth synopsis of the episodes screened, visit https://tardis.fandom.com/ wiki/The_End_of_Time_(TV_story). To see additional Doctor Who episodes screened by Fath- om, go to https://tardis.fandom.com/wiki/Fathom_Events. And if you’d like to learn about up- coming Fathom screenings, check out https://www.fathomevents.com/search?q=doctor+who. The episodes are also available on DVD: https://amzn.to/2KuSITj. The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance on Netflix Review by Jim McCoy (I would never do this before a book review, but I doubt that the people at Netflix would mind, so here goes: I'm geeked. -

The Multidimensional Guide to Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Twentieth Century, Volume 1

THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL GUIDE TO SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY, VOLUME 1 EDITED BY NAT TILANDER 2 Copyright © 2010 by Nathaniel Garret Tilander All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted by any means—whether auditory, graphic, mechanical, or electronic—without written permission of both publisher and author, except in the case of brief excerpts used in critical articles and reviews. Unauthorized reproduction of any part of this work is illegal and is punishable by law. Cover art from the novella Last Enemy by H. Beam Piper, first published in the August 1950 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, and illustrated by Miller. Image downloaded from the ―zorger.com‖ website which states that the image is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain License. Additional copyrighted materials incorporated in this book are as follows: Copyright © 1949-1951 by L. Sprague de Camp. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1951-1979 by P. Schuyler Miller. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1975-1979 by Lester Del Rey. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1978-1981 by Spider Robinson. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1979-1999 by Tom Easton. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1950-1954 by J. Francis McComas. These articles originally appeared in Fantasy and Science Fiction. Copyright © 1950-1959 by Anthony Boucher. These articles originally appeared in Fantasy and Science Fiction. Copyright © 1959-1960 by Damon Knight. These articles originally appeared in Fantasy and Science Fiction. -

Vop #141 / 3 Are on My Own Recommended Reading List, So I Ordered the Following Books

Visions of Paradise #141 Visions of Paradise #141 Contents Out of the Depths...............................................................................................page 3 Favorite SF Movies ... Paperback Swap Will F. Jenkins Day..............................................................................................page 4 A celebration of the life and career of Murray Leinster The Passing Scene................................................................................................page 6 Homes ... May 2009 Wondrous Stories................................................................................................page 9 Going For Infinity … F&SF ... Deathworld ... Heat On the Lighter Side............................................................................................page 13 _\\|//_ ( 0_0 ) ___________________o00__(_)__00o_________________ Robert Michael Sabella E-mail [email protected] Personal blog: http://adamosf.blogspot.com/ Sfnal blog: http://visionsofparadise.blogspot.com/ Fiction blog: http://bobsabella.livejournal.com/ Available online at http://efanzines.com/ Copyright ©May 2009, by Gradient Press Available for trade, letter of comment or request Artwork Franz H. Miklis … Cover Terry Jeeves … p. 9 http://www.sfsite.com/~silverag/leinster.html … page 4 Out of The Depths I am not a huge movie fan, partly because I don’t have a lot of available time to watch them (without depleting my limited reading time), and partly because movies rarely interest me as much as a good book does. So when I was -

Vector 31 Peyton 1965-03

THE JOURNAL OF THE BRITISH SCIENCE FICTION ASSOCIATION Number 31 March 19&5 ******************************************************************** President * CONTENTS Page * * EDITORIAL . a . *................................................................ 2 * * * * ♦ Chairman * THE WORLD SAVER RETURNS — Edmona * Hamilton in focus by Terry Bull ... 3 Kenneth M P Cheslin 18 New Farm Road * * Stourbridgej Worcs* * BALLARD’S TERMINAL BEACH by Peter White 9 * * * * * Vice-Chairman * FOR TOUR INFORMATION by Jim Groves. • .11 Roy Kay * 91 Craven Street Birkenhead, Cheshire * GENERAL CHUNTERING by Ken Slater. .15 * * * * Secretary * IN MEMORIUM: H BEAM PIPER * by Pete Weston, ..................... »17 Graham J Bullock 14 Crompton Road * Tipton, Staffs. * BOOKS : REVIEWS AND NEWS............... 19 * * * * Treasurer * Art Credits Ken McIntyre (front and Charles Winstone * back covers); Phil Harbottle (pgs 3»6); 71 George Road * Dick Howett (pgs 9,18) ; Terry Jeeves (pg Erdington, Birmingham 23 * 11); Richard Gordon (pg 16); all other * lettering by the editor. * * * * * VECTOR is published eight times a year. Publications Officer * It is distributed free to members of the and Editor * British Science Fiction Association and Roger G Peyton * is not available to the general public, 77 Grayswood Park Road * All material, artwork, letters of comment Quinton, Birmingham 32 * etc. for or concerning VECTOR should be * * * * addressed to the Editor (address * opposite). Books and magazines for Librarian review should be sent c/o the Librarian Joe Navin -

WSFA Journal 69

. »x.'N ■ •*' p. l^-> = f/M'i/ilf'if'''-. ///" fiii: It I - . ■I»'• n, ll i.^/f f •] ! i W 'i j :i m y't ) ' ' / •* ' - t *> '.■; ■ *"<* '^ii>fi<lft'' f - ■ ■//> ■ vi '' • ll. F V -: ■ :- ^ ■ •- ■tiK;- - :f ii THE WSFA journal (The Official Organ of the Washington Science Fiction Association) Issue Number 69: October/November, 1969 The JOURNAL Staff — Editor & Publisher: Don Miller, 12315 Judson Rd., Wheaton, Maryland, .•U.S.A., 20906. ! Associate Editors: Alexis & Doll Gilliland, 2126 Pennsylvania Ave,, N.W., Washington, D.C., U.S.A., 20037. Cpntrib-uting Editors:- ,1 . " Art Editor — Alexis Gilliland. - 4- , . Bibliographer— Mark Owings. Book Reviewers — Alexis Gilliland,• David Haltierman, Ted Pauls. Convention Reporter — J.K. Klein. ' : . r: Fanzine Reviewer — Doll Golliland "T Flltfl-Reviewer — Richard Delap. ' " 5 P^orzine Reviewer — Banks.Mebane. Pulps — Bob Jones. Other Media Ivor Rogers. ^ Consultants: Archaeology— Phyllis Berg. ' Medicine — Bob Rozman. Astronomy — Joe Haldeman. Mythology — Thomas Burnett Biology — Jay Haldeman. Swann, David Halterman. Chemistry — Alexis Gilliland. Physics — Bob Vardeman. Computer Science — Nick Sizemore. Psychology -- Kim West on. Electronics — Beresford .Smith. Mathematics — Ron Bounds, Steve Lewis. Translators: . French .— Steve Lewis, Gay Haldeman. Russian — Nick Sizemore, German -- Nick Sizemore. Danish ~ Gay. Haldeman, Italian ~ OPEN. Joe Oliver. Japanese. — OPEN. Swedish" -- OBBN. Overseas Agents: Australia — Michael O'Brien, 158 Liverpool St., Holaart, Tasmania, Australia, 7000. • South Africa — A.B. Ackerman, P^O.Box 6, Daggafontein, .Transvaal, South Africa, . ^ United Kingdom — Peter Singleton, 60ljU, Blodc h, Broadiiioor Hospital, Crowthome, Berks, RGll 7EG, United Kingdom. Needed for France, Germany, Italy, Scandinavia, Spain, S.America, NOTE; Where address are not listed above, send material ^Editor, Published bi-monthly.