3.3 the Oracle Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

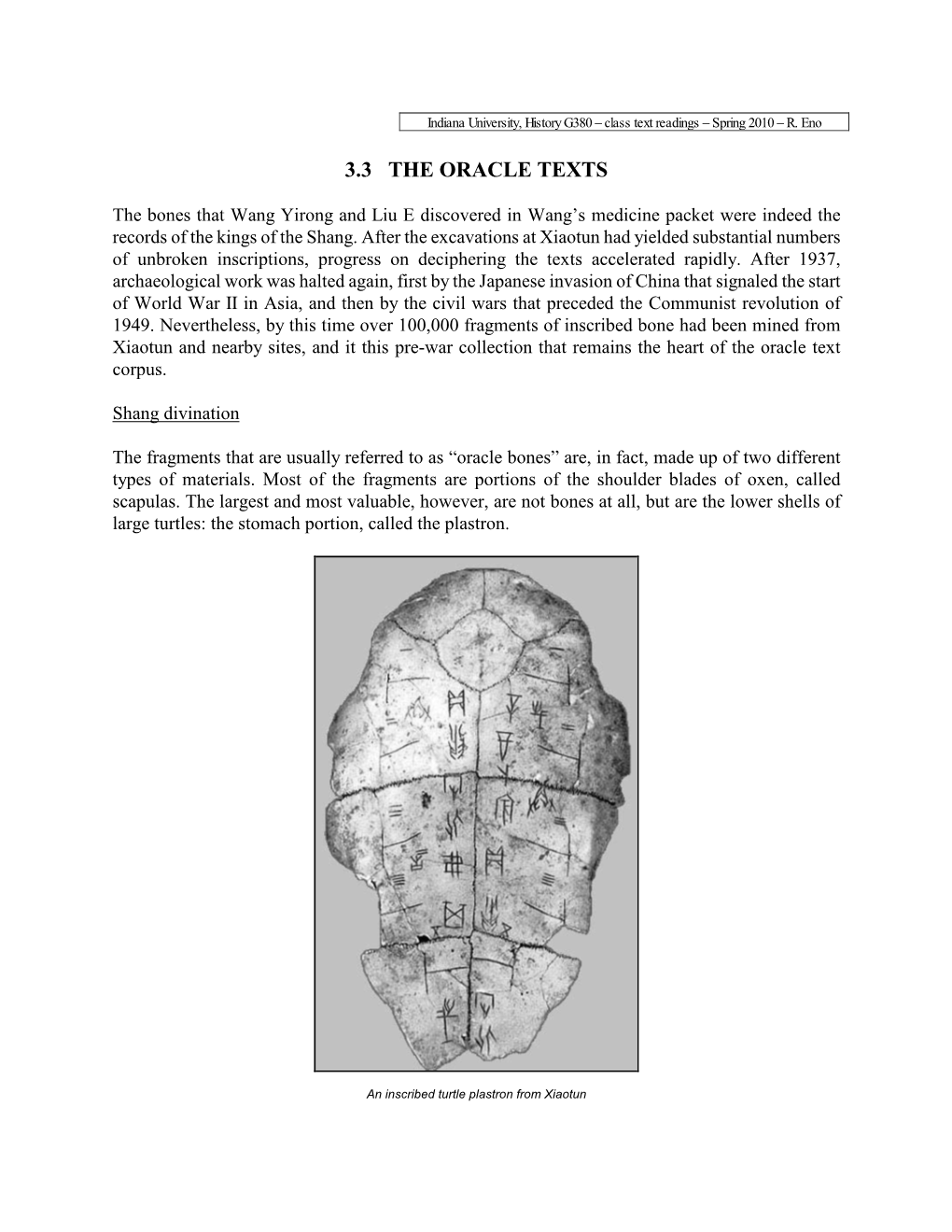

Recommended publications

-

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional Sections Contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional sections contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D. Ph.D. Introduction Nichole Yalsovac Prophetic revelation, or Divination, dates back to the earliest known times of human existence. The oldest of all Chinese texts, the I Ching, is a divination system older than recorded history. James Legge says in his translation of I Ching: Book Of Changes (1996), “The desire to seek answers and to predict the future is as old as civilization itself.” Mankind has always had a desire to know what the future holds. Evidence shows that methods of divination, also known as fortune telling, were used by the ancient Egyptians, Chinese, Babylonians and the Sumerians (who resided in what is now Iraq) as early as six‐thousand years ago. Divination was originally a device of royalty and has often been an essential part of religion and medicine. Significant leaders and royalty often employed priests, doctors, soothsayers and astrologers as advisers and consultants on what the future held. Every civilization has held a belief in at least some type of divination. The point of divination in the ancient world was to ascertain the will of the gods. In fact, divination is so called because it is assumed to be a gift of the divine, a gift from the gods. This gift of obtaining knowledge of the unknown uses a wide range of tools and an enormous variety of techniques, as we will see in this course. No matter which method is used, the most imperative aspect is the interpretation and presentation of what is seen. -

The Adorabyssal Oracle

THE ADORABYSSAL ORACLE The Adorabyssal Oracle is an oracle deck featuring the cutest versions of mythological, supernatural, and cryptozoological creatures from around the world! Thirty-six spooky cuties come with associated elements and themes to help bring some introspection to your day-to-day divinations and meditations. If you’re looking for something a bit more playful, The Adorabyssal Oracle deck doubles as a card game featuring those same cute and spooky creatures. It is meant for 2-4 players and games typically take 5-10 minutes. If you’re interested mainly in the card game rules, you can skip past the next couple of sections. However you choose to use your Adorabyssal Deck, it is my hope that these darkly delightful creatures will bring some fun to your day! WHAT IS AN ORACLE DECK? An Oracle deck is similar to, but different from, a Tarot deck. Where a Tarot deck has specific symbolism, number of cards, and a distinct way of interpreting card meanings, Oracle decks are a bit more free-form and their structures are dependent on their creators. The Adorabyssal Oracle, like many oracle decks, provides general themes accompanying the artwork. The basic and most prominent structure for this deck is the grouping of cards based on elemental associations. My hope is that this deck can provide a simple way to read for new readers and grow in complexity from there. My previous Tarot decks have seen very specific interpretation and symbolism. This Oracle deck opens things up a bit. It can be used for more general or free-form readings, and it makes a delightful addition to your existing decks. -

African Concepts of Energy and Their Manifestations Through Art

AFRICAN CONCEPTS OF ENERGY AND THEIR MANIFESTATIONS THROUGH ART A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Renée B. Waite August, 2016 Thesis written by Renée B. Waite B.A., Ohio University, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Fred Smith, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Michael Loderstedt, M.F.A., Interim Director, School of Art ____________________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, D.Ed., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………….. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …………………………………… vi CHAPTERS I. Introduction ………………………………………………… 1 II. Terms and Art ……………………………………………... 4 III. Myths of Origin …………………………………………. 11 IV. Social Structure …………………………………………. 20 V. Divination Arts …………………………………………... 30 VI. Women as Vessels of Energy …………………………… 42 VII. Conclusion ……………………………………….…...... 56 VIII. Images ………………………………………………… 60 IX. Bibliography …………………………………………….. 84 X. Further Reading ………………………………………….. 86 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Porogun Quarter, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria, 1992, Photograph by John Pemberton III http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/cosmos/models.html. ……………………………………… 60 Figure 2: Yoruba Ifa Divination Tapper (Iroke Ifa) Nigeria; Ivory. 12in, Baltimore Museum of Art http://www.artbma.org/. ……………………………………………… 61 Figure 3.; Yoruba Opon Ifa (Divination Tray), Nigerian; carved wood 3/4 x 12 7/8 x 16 in. Smith College Museum of Art, http://www.smith.edu/artmuseum/. ………………….. 62 Figure 4. Ifa Divination Vessel; Female Caryatid (Agere Ifa); Ivory, wood or coconut shell inlay. Nigeria, Guinea Coast The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. ……………………… 63 Figure 5. Beaded Crown of a Yoruba King. Nigerian; L.15 (crown), L.15 (fringe) in. -

D I V I N a T I O N Culture a N D the H a N D L I N G of The

Originalveröffentlichung in: G. Leick (Hrsg), The Babylonian World, New York/London, 2007, S. 361-372 CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE DIVINATION CULTURE AND THE HANDLING OF THE FUTURE Stefan M. Maul n omen is a clearly defined perception understood as a sign pointing to future A events whenever it manifests itself under identical circumstances. The classification of a perception as ominous is based on an epistemological development which establishes a normative relationship between the perceived and the future. This classification process is preceded by a period of detailed examination and is thus initially built on empirical knowledge. Omina only cease to be detected empirically when a firm conceptual link has been established between the observed and the future which then allows omina to be construed by the application of regularities. In the Mesopotamian written sources from the first and second millennia BC, omina based on regularities far exceed those based on empirical data. Mesopotamian scholars generally collected data without formally expressing the fundamental principles behind their method. It was the composition of non-empirical omina as such which allowed students to detect the regularities on which they were based without this formulated orally or in writing. Modern attempts at a systematic investigation of such principles however, are still outstanding. It is interesting that there is no Sumerian or Akkadian equivalent for the terms 'oracle' or 'omen'. Assyriologists use the term omen for the sentence construction 'if x then y' which consists of a main clause beginning with summa ('if') describing the ominous occurence, and a second clause which spells out the predicted outcome. -

And Corpse-Divination in the Paris Magical Papyri (Pgm Iv 1928-2144)

necromancy goes underground 255 NECROMANCY GOES UNDERGROUND: THE DISGUISE OF SKULL- AND CORPSE-DIVINATION IN THE PARIS MAGICAL PAPYRI (PGM IV 1928-2144) Christopher A. Faraone The practice of consulting the dead for divinatory purposes is widely practiced cross-culturally and firmly attested in the Greek world.1 Poets, for example, speak of the underworld journeys of heroes, like Odys- seus and Aeneas, to learn crucial information about the past, present or future, and elsewhere we hear about rituals of psychagogia designed to lead souls or ghosts up from the underworld for similar purposes. These are usually performed at the tomb of the dead person, as in the famous scene in Aeschylus’ Persians, or at other places where the Greeks believed there was an entrance to the underworld. Herodotus tells us, for instance, that the Corinthian tyrant Periander visited an “oracle of the dead” (nekromanteion) in Ephyra to consult his dead wife (5.92) and that Croesus, when he performed his famous comparative testing of Greek oracles, sent questions to the tombs of Amphiaraus at Oropus and Trophonius at Lebedeia (1.46.2-3). Since Herodotus is heavily dependent on Delphic informants for most of Croesus’ story, modern readers are apt to forget that there were, in fact, two oracles that correctly answered the Lydian king’s riddle: the oracle of Apollo at Delphi and that of the dead hero Amphiaraus. The popularity of such oracular hero-shrines increased steadily in Hel- lenistic and Roman times, although divination by dreams gradually seems to take center stage.2 It is clear, however, that the more personal and private forms of necromancy—especially consultations at the grave—fell into disfavor, especially with the Romans, whose poets repeatedly depict horrible 1 For a general overview of the Greek practices and discussions of the specific sites mentioned in this paragraph, see A. -

The Soteriological Context of a Tibetan Oracle

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 39 Number 1 Article 8 July 2019 The Soteriological Context of a Tibetan Oracle Katarina Turpeinen University of California, Berkeley, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Turpeinen, Katarina. 2019. The Soteriological Context of a Tibetan Oracle. HIMALAYA 39(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol39/iss1/8 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Soteriological Context of a Tibetan Oracle Acknowledgements The author would like to thank Lhamo Pema Khandro for patiently answering her questions in a series of interviews and allowing her to witness the possession rituals. She is also grateful to the nuns of Tsho Pema, especially Ani Yangtsen Drolma for guiding her in the social dynamics of the village, as well as Prof. Jacob Dalton for offering many helpful suggestions that shaped her writing. This research article is available in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol39/iss1/8 The Soteriological Context of a Tibetan Oracle Katarina Turpeinen This paper contributes to the study of Tibetan which is a practice of a village oracle often oracles by analyzing a distinctive case of a regarded as involving mainly mundane and contemporary Tibetan oracle living in exile pragmatic ends, is conspicuously integrated in India. -

Then Apply the Ancient African IFA Oracle (And Its Subset the I Ching) to Describe History, Including the Future History of Global Finance

Abstract Dan Brown in his 2009 book "The Lost Symbol" said "... The ancients possessed profound scientific wisdom. ... Mankind ... had once grasped the true nature of the universe ... but had let go ... and forgotten. ... Modern physics can help us remember! ... the world need[s] this understanding ... now more than ever. ...", but the rest of his book fails to provide convincing support for that statement, although it does provide a clue: "... The secret hides within the Order Eight Franklin Square ... of the numbers 1 through 64 ...". The purpose of this paper is to support that statement in enough detail to convince a diligent reader that following that clue can show that the statement is true. To follow the clue: begin with the "Order Eight" Clifford Algebra Cl(8) whose 2^8 = 256 dimensions represent the 256 elements of the Ancient African IFA Oracle and the 256 Elementary Cellular Automata, so that the True Lost Symbol is the 8-dimensional HyperCube with 256 vertices as shown on the cover of this paper; then multiply (by tensor product) 8 copies of Cl(8) to produce Cl(64) whose 2^64 dimensions represent the first 10^(-34) seconds of the Zizzi Inflation Phase of our Conscious Universe and an event of Penrose-Hameroff Human Conscious Thought; then analyze the details of the 256 Cellular Automata and the E8 Lattices containing 256-vertex 8-dimensional HyperCubes to construct a realistic unified theoretical model of the Standard Model plus Gravity; then analyze the Fractal Structure of the Ancient African IFA Oracle; then apply the Ancient African IFA Oracle (and its subset the I Ching) to describe History, including the Future History of Global Finance. -

Why Explaining Religion Is Not Sufficient to Explain Away Religion

Why Explaining Religion Is Not Sufficient to Explain Away Religion An argumentative exploration of the leading evolutionary explanatory accounts of religion to demonstrate the inability of science to explain away religious belief Author: Vipusaayini Sivanesanathan Edited by: Ko-Lun Liu 1. Introduction While science continues to make significant progressive strides, religion has yet to add to its historically established doctrines. Not only has the rapid expansion of science brought into question the validity and necessity of religion, part of scientific inquiry now focuses on how ‘counterintuitive’ notions of religion came to be. ‘Counterintuitive’ ideas of religion posit religious beliefs to go against or violate empirically verified facts or knowledge. Some argue that we can utilize the knowledge attained from advancements in science to explain away religion. One particular aspect of science that is used to explain away religion are evolutionary theories. In this paper, I will argue that while evolutionary accounts can explain our affinity towards religion, it has yet to explain away religion. I will explicate and refute the three different argument for evolutionary accounts of religion, including the socio-evolutionary, bio-evolutionary and cultural-evolutionary, to demonstrate how science has not succeeded in explaining away religion. 2. Why Does Science Try to Explain Away Religion? There is a prominent assumption in academia that science and religion are two separate and distinct fields which fundamentally do not, and (for some) cannot overlap. Both science and theism attempt to answer the central questions concerning the design and function of natural phenomena (i.e., evolution, questions of the universe, life etc). -

100 Necromancers and Their Plots 6

100 Necromancers and their Plots 6. Helosia Tremastag A grim beauty dwells in a ruined temple outside of town and is trying to drain beauty from other maidens. Her giant 1. Kustarg Durmargis undead ravens kidnap the girls from their beds. A middle aged necromancer who sets his students to work 7. Lady Marsia Beradee building a defence force of basic undead. From his Bathes in blood of young girls to retain her beauty. Her underground lair he has been seeking to plumb the secrets servants are helping her and she spends far too much time of a well reputed to hold a fragment of a dead god. with pretty young men to perfect the process. Any men 2. Dr Nosterang Barlanth who see her change to her true age her servants kill. Her A portly bespectacled dissections and flesh golem maker incomplete research keeps turning up after her destruction, has students grave robbing terrorising locals who fear spreading the cycle of death forever. relatives bodies being robbed. A pit filled with reject 8. Kiasaar Mendloth creations has started to make lots of noises. Had all her kin die in a plague but has returned them as 3. Lady Pahrzethra Molochi undead to serve her. She tries to cover it with illusions and A beautiful widow has been poisoning young men about invites travelers into her luxurious but dusty and a bit town to be her undead consorts, her students procure her stinky home. If they see the true horror she sets her kin to the bodies of those who she kills from afar. -

Hunter, Shaman, Oracle, Priest : an Ethnohistorical Overview of Inspirational Practices in Highland Georgia

Hunter, shaman, oracle, priest : An ethnohistorical overview of inspirational practices in highland Georgia. Kevin Tuite Université de Montréal Sixth Harvard Round Table on Archaeology, Language, Genetics and Comparative Mythology May 2004 [email protected] www.philologie.com SOME APPROACHES TO THE DEFINITION OF SHAMANISM 1. STADIALIST (e.g. Lev Shternberg’s theory of divine election [izbrannichestvo]) 2. PROTOTYPE-BASED (cp. Eliade’s shamanic prototype primarily drawn from Siberian data: ecstatic voyage to sky or underworld, mastery of fire, psychopomp) 3. CULTURALLY-SITUATED (cp. R. Hamayon’s definition of shaman’s role in terms of imagined alliance and gender asymmetries, contrasting it to spirit possession — Prototypical shaman adopts a masculine role, as imagined by his society, as an active seeker of women and resources outside of the community. Possession, by contrast, is a passive and stereotypically feminine stance: the possessed does not seek, but rather is sought, by the soul or spirit that seizes her) 4. POLITICALLY/HISTORICALLY/SOCIALLY-SITUATED (cp. contributions to N. Thomas & C. Humphreys 1994 Shamanism, history, and the state, which seek to “loos[en] the classificatory paradigms” left by Eliade, in favor of a “historical anthropology of inspirational practices”, that situates shamanism and shamans in their historical and political context) PREVIOUS ATTEMPTS TO IDENTIFY SHAMANISM IN THE CAUCASUS 1. G. Nioradze (1940) likened Abkhazian and Georgian “soul-returning” rituals to similar practices performed by Buryat shamans. 2. R. Bleichsteiner (1936) on “Reste von Schamanismus” in ethnographic descriptions from the highland provinces of northeast Georgia, in particular, those of Pshavi and Xevsureti (subsequently cited by Eliade in his monograph). -

The Chrēsmologoi in Thucydides

The Chr ēsmologoi in Thucydides Michael Zimm It is clear to any reader of Thucydides’ History that the concern with the gods and the supernatural, which is so prevalent in the Histories of Herodotus, is strikingly lacking. Whenever Thucydides refers to the supernatural in the narrative proper, 1 he tends to emphasize the misinterpretation of an oracle or its ambiguity. 2 Thucydides even mentions oracles derisively in the section on the plague and in the so-called ‘second introduction.’3 However, this is not to say that Thucydides did not believe in the gods of traditional Greek religion, but rather that, for the most part, he discounted them as forces that directly influence human events. 4 There has been much scholarly debate on the nature of both Thucydides’ personal beliefs and his skepticism concerning oracles, and it is not my intention to deal with this particular topic in this paper. 5 I would rather like to focus on Thucydides’ portrayal of a group of purveyors of oracles, namely, the chr ēsmologoi .6 1 I would like to thank Jonathan Price, Margalit Finkelberg, Emily Greenwood, David Konstand, Pura Nieta, Benjamin Isaac, and Jeffrey Rusten for their encouragement and suggestions. I am also grateful to the anonymous readers of SCI and the editors who read earlier drafts of the paper and lent encouraging words. This paper does not consider the speeches which raise different methodological questions. All translated passages are taken from The History of the Peloponnesian War , translated by R. Crawley and revised by D. Lateiner (New York: 2006). 2 Thucydides uses several words for oracles and oracular activities: crh'sqai (1.123; 2.102; 5.16; 5.32; 1.126; 3.96), crhsmov" (2.21; 3.104; 5.26; 5.103), crhsthvrion (1.25; 1.103; 2.54), mantikhv (5.103), manteuvesqai (5.18), and mantei'on (1.25; 1.28; 2.17; 2.47; 4.118). -

Ancient Divination and Experience OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 11/9/2019, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 11/9/2019, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 11/9/2019, SPi Ancient Divination and Experience OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 11/9/2019, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 11/9/2019, SPi Ancient Divination and Experience Edited by LINDSAY G. DRIEDIGER-MURPHY AND ESTHER EIDINOW 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Oxford University Press 2019 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2019 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of this licence should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2019934009 ISBN 978–0–19–884454–9 DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198844549.001.0001 Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only.