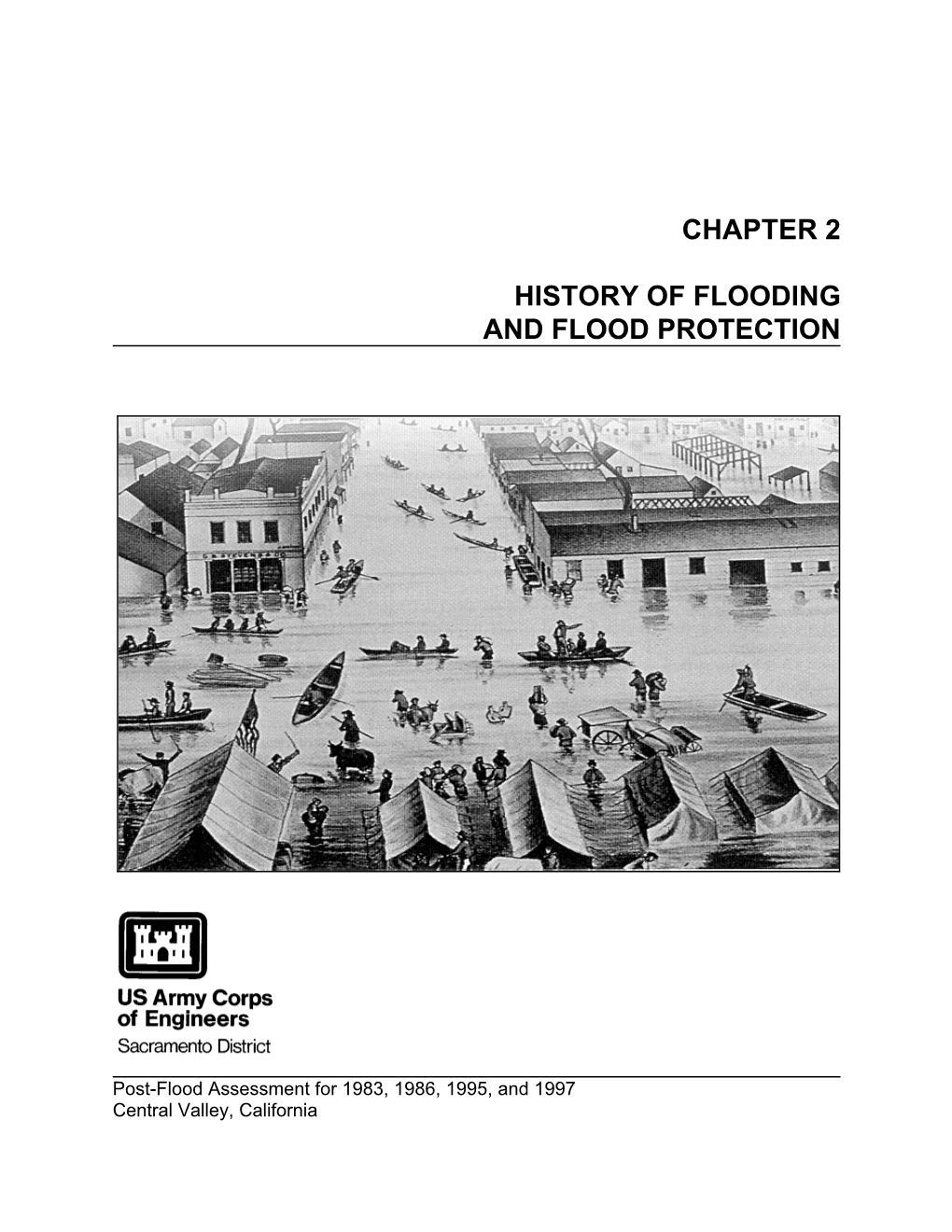

History of Flooding and Flood Protection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Valley Project Overview July 2013 Central Valley of California

Central Valley Project Overview July 2013 Central Valley of California TRINITY DAM FOLSOM DAM LV SL Hydrologic Constraints • Majority of water supply in the north • Most of the precipitation is in the winter/spring • Majority of demand in the south • Most of that demand is in the summer Geographic Constraints Sacramento/San Joaquin Delta Avg Annual Inflow in MAF (Billion Cu Meters) (5.3) 4.3 (1.7) 1.4 (1.1) 0.9 21.2 (26.2) Sacramento Delta Precip Eastside Streams San Joaquin California Water Projects • State Water Project • Central Valley Project • Local Water Projects Trinity CVP Shasta Major Storage Folsom Facilities New Melones Friant San Luis Trinity CVP Shasta Conveyance Folsom Facilities New Melones Friant San Luis CVP Features Summary • 18 Dams and Reservoirs • 500 Miles (800 Kilometers) of Canals • 11 Powerplants • 10 Pumping Plants • 20 Percent of State’s Developed Water Supply (about 7 million acre-feet, 8.6 billion cu meters) • 30 Percent of the State’s Agricultural Supply (about 3 mil acres of farm land, 1.2 mil hectares) • 13 Percent of State’s M&I Supply (about 2 million people served) CVP Authorized Purposes • Flood Control • River Regulation (Navigation) • Fish and Wildlife Needs • Municipal & Agricultural Water Supplies • Power Generation • Recreation TRINITY CVP - SWP FEATURES LEWISTON SHASTA SPRING CREEK POWERPLANT CARR POWERPLANT TINITY RIVER WHISKEYTOWN OROVILLE (SWP) TO SAN FRANCISCO BAY DELTA FOLSOM BANKS PP (SWP) JONES PP NEW MELONES O’NEILL TO SAN FELIPE SAN LUIS FRIANT TRINITY CVP - SWP FEATURES LEWISTON SHASTA -

Two-Dimensional Hydraulic Model of Folsom Dam

Michael Pantell, E.I.T. Peterson Brustad Inc. • Model Folsom Dam Flood Scenarios • During Probable Maximum Flood (PMF) • Varying Folsom Dam Outflows • Multiple Breach Locations and Methods • Results • Floodplain Depths • Mortality • Property Damage • Why? • Information not Available to public • To Obtain Masters Degree Built in 1956 Owned by USBR Storage Approx. 1 Mil Ac-ft 12 structures Concrete Main dam Earthen 2 Wing Dams 1 Auxiliary Dam Reference: USBR “Folsom Dam Facility Map” 8 Dikes Sacramento Folsom River Reservoir Sacramento American River Probable Maximum Flood American River 1000000 900000 Peak ≈ 900,000 cfs Basin 800000 700000 PMF 600000 ) cfs Developed by 500000 Flow ( USACE 400000 300000 Project Design 200000 Flood 100000 0 0 12 24 36 48 60 72 84 96 108 120 132 144 156 168 180 192 Approx. 25,000 Time (hours) year event Auxiliary Spillway Powerhouse Folsom Dam Flow = 6900 cfs 8 Tainter Gates 5- Main 3- Emergency Auxiliary Spillway Designed to PMF event Dam Outflow 500 PMF Event 490 Overtopping 480 Elevation 470 460 450 440 430 420 410 400 Elevation (NAVD88 feet) Elevation 390 380 370 360 350 50000 100000 150000 200000 250000 300000 350000 400000 450000 500000 550000 600000 650000 700000 750000 800000 850000 900000 950000 1000000 Outflow (CFS) Without Spillway With Spillway Mechanisms Overtopping Piping Earthquake Etc Right Wing Dam Northern Breach Mormon Auxiliary Dam Southern Breach Tallest and longest earthen structures North Earthen structure South Earthen structure LargerMacDonald Breach Von Thun = Longer & MacDonald Formation Von TimeThun & ∝ MacDonald, et. al.et. al. Gillette et. al. Gillette Large Breach Width Long- ft Formation3047 Time 374 3916 331 Von Thun & Gillete Height Small- ft Breach 47 47 76 76 Short Formation Time Formation 4.4 0.8 4.1 0.7 Time (hrs) HEC RAS 5.0 2D Mesh 150 m x 150 m Terrain CVFED 1 m resolution Manning’s n Based on CVFED Land Use Jonkman et. -

Attachment 1 Credentials of Trlia Board of Senior Consultants

ATTACHMENT 1 CREDENTIALS OF TRLIA BOARD OF SENIOR CONSULTANTS FAIZ I. MAKDISI, PH.D., P.E. PRINCIPAL ENGINEER EDUCATION SKILLS AND EXPERIENCE Ph.D., Geotechnical Dr. Makdisi’s 28-year career has combined applied research and Engineering, University of professional practice in geotechnical and foundation/earthquake California, Berkeley, 1976 engineering for commercial, residential, industrial, and critical M.Sc., Geotechnical structures. Recently he has focused on geotechnical studies and safety Engineering, University of evaluations of earth and rockfill dams, embankments, and landfills. His California, Berkeley, 1971 work includes feasibility evaluations and preliminary design studies; field investigation design and planning; borrow area material studies; in B. Eng., Civil, American situ and laboratory testing; and evaluation and interpretation of static University of Beirut: and dynamic material properties of dams and their foundations. Studies Lebanon, 1970 also included stability evaluations of embankment slopes, seepage analyses, and static and dynamic stress analyses to evaluate stability REGISTRATION during earthquakes. Professional Civil Engineer, He has performed studies to determine earthquake-induced permanent CA No. C29432, 1978 deformations in slopes and embankments, and developed and published Civil Engineer, Institute of widely used simplified procedures for estimating dynamic response and Civil Engineers, Lebanon, permanent deformations in earth and rockfill dams and embankments. 1970 He is a lead participant in earthquake ground motion studies and development of seismic design criteria for key facilities such as dams AFFILIATIONS and nuclear power plants. He was principal investigator of the “Stability American Society of Civil of Slopes, Embankments and Rockfalls” chapter of the Seismic Retrofit Engineers Manual for the Federal Highway Project being prepared for the National Earthquake Engineering Center for Earthquake Engineering Research. -

Mokelumne/Amador/Calaveras Integrated Regional Water Management Plan

Mokelumne/Amador/Calaveras Integrated Regional Water Management Plan November 2006 Mokelumne/Amador/Calaveras Integrated Regional Water Management Plan Prepared by: Water and Environment November 2006 Mokelumne, Amador, and Calaveras IRWMP Table of Contents Executive Summary..................................................................................................................... i ES-1 Background and Authority........................................................................................... i ES-2 Local and Regional Integration .................................................................................. ii ES-3 Goals and Objectives .................................................................................................iii ES-4 Project Prioritization ...................................................................................................iii ES-5 Implementation.......................................................................................................... iv Chapter 1 Introduction ...........................................................................................................1-1 1.1 IRWMP Background................................................................................................1-1 1.2 IRWMP Standards ..................................................................................................1-2 Chapter 2 M/A/C IRWMP Development .................................................................................2-1 2.1 Resource Management & Coordination -

Notice of Special Meeting

BOARD OF DIRECTORS EAST BAY MUNICIPAL UTILITY DISTRICT 375 - 11th Street, Oakland, CA 94607 Office of the Secretary: (510) 287-0440 Notice of Special Meeting FY22 and FY23 Budget Workshop #2 Tuesday, March 23, 2021 9:00 a.m. **Virtual** At the call of President Doug A. Linney, the Board of Directors has scheduled a Budget Workshop for 9:00 a.m. on Tuesday, March 23, 2021. Due to COVID-19 and in accordance with the most recent Alameda County Health Order, and with the Governor’s Executive Order N-29-20 which suspends portions of the Brown Act, this meeting will be conducted by webinar or teleconference only. In compliance with said orders, a physical location will not be provided for this meeting. These measures will only apply during the period in which state or local public health officials have imposed or recommended social distancing. The Board will meet in workshop session to review the proposed Fiscal Year 2022 (FY22) and Fiscal Year 2023 biennial budget, rates, operating and capital priorities, and staffing; the proposed FY22 System Capacity Charge and FY22 Wastewater Capacity Fee; and will receive follow-up information from the January 26, 2021 Budget Workshop #1. Dated: March 18, 2021 _______________________________ Rischa S. Cole Secretary of the District W:\Board of Directors - Meeting Related Docs\Notices\Notices 2021\032321_FY22_FY23 Budget Workshop 2.docx This page is intentionally left blank. BOARD OF DIRECTORS EAST BAY MUNICIPAL UTILITY DISTRICT 375 - 11th Street, Oakland, CA 94607 Office of the Secretary: (510) 287-0440 AGENDA Special Meeting FY22 and FY23 Budget Workshop #2 Tuesday, March 23, 2021 9:00 a.m. -

Grants of Land in California Made by Spanish Or Mexican Authorities

-::, » . .• f Grants of Land in California Made by Spanish or Mexican Authorities Prepared by the Staff of the State Lands Commission ----- -- -·- PREFACE This report was prepared by Cris Perez under direction of Lou Shafer. There were three main reasons for its preparation. First, it provides a convenient reference to patent data used by staff Boundary Officers and others who may find the information helpful. Secondly, this report provides a background for newer members who may be unfamiliar with Spanish and Mexican land grants and the general circumstances surrounding the transfer of land from Mexican to American dominion. Lastly, it provides sources for additional reading for those who may wish to study further. The report has not been reviewed by the Executive Staff of the Commission and has not been approved by the State Lands Commission. If there are any questions regarding this report, direct them to Cris Perez or myself at the Office of the State Lands Commission, 1807 - 13th Street, Sacramento, California 95814. ROY MINNICK, Supervisor Boundary Investigation Unit 0401L VI TABLE OF CONTENlS Preface UI List of Maps x Introduction 1 Private Land Claims in California 2 Missions, Presidios, and Pueblos 7 Explanation of Terms Used in This Report 14 GRANTS OF LAND BY COUNTY AlamE:1da County 15 Amador County 19 Butte County 21 Calaveras County 23 Colusa County 25 Contra Costa County 27 Fresno County 31 Glenn County 33 Kern County 35 Kings County 39 Lake County 41 Los Angeles County 43 Marin County 53 Mariposa County 57 Mendocino County -

Folsom Dam Joint Federal Project

-BUREAU OF - RECLAMATION Folsom Dam Joint Federal Project Background Folsom Dam was authorized in 1944 as a 355,000 acre-foot flood control unit and then reauthorized in 1949 as an almost 1 million acre-foot multiple-purpose facility. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) completed construction in 1956 and then transferred the dam to the Bureau of Reclamation for coordinated operation as an integral part of the federal Central Valley Project. Folsom Dam regulates flows in the American River for flood control, and releases from Folsom Reservoir are used for municipal and industrial water supply, agricultural water supply, power, fish and wildlife management, recreation, navigation and water quality purposes. Recreation at Folsom Reservoir is managed by the California Department of Parks and Recreation under an agreement with Reclamation. The Folsom Facility Managed by the Central California Area Office (CCAO), the Folsom Facility comprises Folsom Dam and Reservoir, left and right earthfill wing dams, Mormon Island Auxiliary Dam and eight earthfill dikes that protect the surrounding communities and the cities of Folsom and Granite Bay. The Sacramento metropolitan area sits in a valley at the confluence of the American and Sacramento Rivers; the valley is a huge floodplain which has flooded countless times over the centuries, and Folsom Dam is the area’s key flood control structure. The Folsom Dam spillway is divided into eight sections, each controlled by a 42-by 50-foot radial gate. The spillway capacity is 567,000 cubic feet per second. Reclamation’s Safety of Dams Program Under the Safety of Dams Program, Reclamation is working to reduce hydrologic (flood), seismic (earthquake) and static (seepage) risks at the Folsom Facility. -

System Reoperation Study

System Reoperation Study Phase III Report: Assessment of Reoperation Strategies California Department of Water Resources August 2017 System Reoperation Study Phase III Report This page is intentionally left blank. August 2017 | 2 Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................................1 -1 1.1 Study Authorization ....................................................................................................................................................................................1 -1 1.2 Study Area ..................................................................................................................................................................................................1 -2 1.3 Planning Principles .....................................................................................................................................................................................1 -4 1.4 Related Studies and Programs...................................................................................................................................................................1 -4 1.5 Uncertainties in Future Conditions ............................................................................................................................................................. 1-6 1.5.1 Climate Change ..........................................................................................................................................................................1 -

Sacramento and Feather Rivers and Their Tributaries, Sacramento Slough and Sutter Bypass

Section 319 NONPOINT SOURCE PROGRAM SUCCESS STORY Stakeholders Cooperate to ReduceCalifornia Diazinon in Runoff from Dormant Season Spray Widespread use of the organophosphate (OP) pesticides diazinon Waterbodies Improved and chlorpyrifos in California’s Central Valley resulted in aquatic toxicity in the Sacramento and Feather rivers and their tributaries, Sacramento Slough and Sutter Bypass. As a result, in 1994 the Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board (CV-RWQCB) added a 16-mile segment of the Sacramento River, a 42-mile segment of the Feather River, the 1.7-mile-long Sacramento Slough, and the 19-mile-long Sutter Bypass to the CWA section 303(d) list of impaired waters. In 2001, the Sacramento River Watershed Program (SRWP) developed and implemented a water quality management strategy for the two rivers, which included installing on-site best management practices (BMPs). Diazinon concentrations decreased, prompting CV-RWQCB to remove Sacramento Slough and Sutter Bypass from the CWA section 303(d) list in 2006. The state has recommended the removal of the Sacramento River and Feather River segments (58 river miles total) from the 2010 CWA section 303(d) list for diazinon impairments. UV162 Figure 1. Problem Map showing The Sacramento River is California’s longest river, Orchards locations of flowing from Mt. Shasta to the confluence with the Sacramento San Joaquin River at the Sacramento-San Joaquin and Feather UV45 Delta. The Feather River is the primary tributary to h rivers g l o u C S and their the Sacramento River (Figure 1). The Sutter Bypass o Colusa k r l e tributaries, u c i v is a floodwater bypass that diverts excess water a R s J a b Sutter from the Sacramento River between two large a Sutter u Y S 30 u UV B S Co. -

San Luis Unit Project History

San Luis Unit West San Joaquin Division Central Valley Project Robert Autobee Bureau of Reclamation Table of Contents The San Luis Unit .............................................................2 Project Location.........................................................2 Historic Setting .........................................................4 Project Authorization.....................................................7 Construction History .....................................................9 Post Construction History ................................................19 Settlement of the Project .................................................24 Uses of Project Water ...................................................25 1992 Crop Production Report/Westlands ....................................27 Conclusion............................................................28 Suggested Readings ...........................................................28 Index ......................................................................29 1 The West San Joaquin Division The San Luis Unit Approximately 300 miles, and 30 years, separate Shasta Dam in northern California from the San Luis Dam on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley. The Central Valley Project, launched in the 1930s, ascended toward its zenith in the 1960s a few miles outside of the town of Los Banos. There, one of the world's largest dams rose across one of California's smallest creeks. The American mantra of "bigger is better" captured the spirit of the times when the San Luis Unit -

Sacramento River Flood Control System

A p pp pr ro x im a te ly 5 0 M il Sacramento River le es Shasta Dam and Lake ek s rre N Operating Agency: USBR C o rt rr reek th Dam Elevation: 1,077.5 ft llde Cre 70 I E eer GrossMoulton Pool Area: 29,500 Weir ac AB D Gross Pool Capacity: 4,552,000 ac-ft Flood Control System Medford !( OREGON IDAHOIDAHO l l a a n n a a C C !( Redding kk ee PLUMAS CO a e a s rr s u C u s l l Reno s o !( ome o 99 h C AB Th C NEVADA - - ^_ a a Sacramento m TEHAMA CO aa hh ee !( TT San Francisco !( Fresno Las Vegas !( kk ee e e !( rr Bakersfield 5 CC %&'( PACIFIC oo 5 ! Los Angeles cc !( S ii OCEAN a hh c CC r a S to m San Diego on gg !( ny ii en C BB re kk ee ee k t ee Black Butte o rr C Reservoir R i dd 70 v uu Paradise AB Oroville Dam - Lake Oroville Hamilton e M Operating Agency: CA Dept of Water Resources r Dam Elevation: 922 ft City Chico Gross Pool Area: 15,800 ac Gross Pool Capacity: 3,538,000 ac-ft M & T Overflow Area Black Butte Dam and Lake Operating Agency: USACE Dam Elevation: 515 ft Tisdale Weir Gross Pool Area: 4,378 ac 3 B's GrossMoulton Pool Capacity: 136,193Weir ac-ft Overflow Area BUTTE CO New Bullards Bar Dam and Lake Operating Agency: Yuba County Water Agency Dam Elevation: 1965 ft Gross Pool Area: 4,790 ac Goose Lake Gross Pool Capacity: 966,000 ac-ft Overflow Area Lake AB149 kk ee rree Oroville Tisdale Weir C GLENN CO ee tttt uu BB 5 ! Oroville New Bullards Bar Reservoir AB49 ll Moulton Weir aa nn Constructed: 1932 Butte aa CC Length: 500 feet Thermalito Design capacity of weir: 40,000 cfs Design capacity of river d/s of weir: 110,000 cfs Afterbay Moulton Weir e ke rro he 5 C ! Basin e kk Cre 5 ! tt 5 ! u Butte Basin and Butte Sink oncu H Flow from the 3 overflow areas upstream Colusa Weir of the project levees, from Moulton Weir, Constructed: 1933 and from Colusa Weir flows into the Length: 1,650 feet Butte Basin and Sink. -

2020 Year in Review — California

2020 Year in Review CALIFORNIA–GREAT BASIN REGION U.S. Department of the Interior January 2021 Mission Statements The Department of the Interior conserves and manages the Nation’s natural resources and cultural heritage for the benefit and enjoyment of the American people, provides scientific and other information about natural resources and natural hazards to address societal challenges and create opportunities for the American people, and honors the Nation’s trust responsibilities or special commitments to American Indians, Alaska Natives, and affiliated island communities to help them prosper. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. 2020 Year in Review: Highlights of Key Initiatives in the California-Great Basin Region Cover Photo: The “Three Shastas:” Shasta Dam, Shasta Lake, and Mount Shasta U.S. Department of the Interior January 2021 2020 Year in Review: Highlights of Key Initiatives in the California-Great Basin Region 3 Contents Welcome from Regional Director Conant ...................................................................................6 Implementing New Central Valley Project Operating Plan......................................7 Annual Report on the Long-Term Operation of the CVP and SWP for Water Year 2020 ......................................................................................................................8 Modernizing Reclamation Infrastructure