Defeasiblepumpkin.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue 4 President’S Message

Spring 2015 Volume 11 • Number 2 In This Issue 4 President’s Message 6 New Board of Directors Profiles 8 The Strategic Plan 12 Revelry 2014 16 The Year In Review President Margo Reid Brown ’81 32 Alumnae Community 38 Student Art Gallery Principal 39 In Memoriam Theresa Rodgers 40 75th Anniversary Celebration Events Board of Directors Tom Kandris, Chair Most Reverend Bishop Myron J. Cotta, Ex Officio Kathleen Deeringer Dr. Pam DiTomasso ’72 Roxanne Elliot ’94 Tom McCaffery Mary Norris Lincoln Snyder, ThePax et Bonum magazine seeks to share with the reader the spirit Director of Catholic Schools, Ex Officio of St. Francis Catholic High School. Stories and pictures of the activities and accomplishments of students, parents, staff and alumnae provide glimpses into the ways in which the school’s mission is carried out and its legacy continues. St. Francis benefactors are gratefully acknowledged in the Annual Report of Donors. St. Francis Catholic High School 5900 Elvas Avenue • Sacramento, CA 95819 Phone: 916.452.3461 • Fax: 916.452.1591 www.stfrancishs.org St. Francis Catholic High School is Fully Accredited by the Schools Commission of the Western Association of Schools and Colleges Western Association of Schools and Colleges: Accrediting Commission for Schools 533 Airport Blvd., Suite 200 • Burlingame, CA 94010 • Phone: 650.696.1060 on the cover Izzy Filigenzi ’16 Night Lights After the Rain Pastel on paper “My interest in art started at a young age, and St. Francis provided me with amazing classes and teachers so that I could branch out and practice this passion of mine. -

Auditions and Callbacks All Actors Must Audition in Order to Participate in the Addams Family Or You’Re a Good Man, Charlie Brown

Spring 2019 Audition Packet For grades 6-12th Welcome to Wolf Performing Arts Center’s spring 2019 season! We are so excited about our upcoming spring season featuring two fantastic, fun-loving musicals. As we have watched our oldest actors develop and sharpen their performance skills, we have also witnessed the growth in them as people. We are so thrilled to offer a program that asks young performers to share, think, create, connect, explore, and challenge their creative minds. What’s even more exciting is welcoming new young performers to join us throughout the year! Actors interested in participating in our spring productions must read this packet thoroughly to learn about the auditions, rehearsals, and performances for each production. This packet includes: Information about rehearsals and performances for The Addams Family and You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown Synopses and character lists for both plays Audition form which is to be completed and handed in at your audition Conflict forms to complete and bring to your audition Auditions and Callbacks All actors must audition in order to participate in The Addams Family or You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown. NOTE: All actors will audition for the directors of The Addams Family and You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown at the same time. Auditions will be held on Tuesday, January 22nd and Wednesday, January 23rd from 5:30-8:00pm. Each actor will sign up for a time slot through our registration system (SEE BELOW for link!). Please plan to be at your audition for approximately an hour. -

The Rivers and Ravines

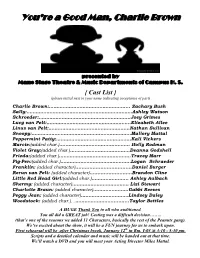

You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown presented by Mane Stage Theatre & Music Departments of Campus H. S. { Cast List } (please initial next to your name indicating acceptance of part) Charlie Brown:……………………………..……………... Zachary Bush Sally:.……………………………………..……………………Ashley Watson Schroeder:.…………………………………………………..Joey Grimes Lucy van Pelt:….………………………….………………..Elizabeth Allee Linus van Pelt:………………………..……………………Nathan Sullivan Snoopy:………………………………………………………..Mallory Mattal Peppermint Patty:………………………………………….Kali Vickers Marcie:(added char.)…..…………………….……………. Holly Rodman Violet Gray:(added char.)….………………….…….……Deanna Godshell Frieda:(added char.)….……………………………….……Tracey Marr Pig-Pen:(added char.)………….………………………..….Logan Schraeder Franklin: (added character)....................................Daniel Burger Rerun van Pelt: (added character)...........................Brandon Cline Little Red Head Girl:(added char.)………..……..….. Ashley Aulbach Shermy: (added character)…………………………….… Lizi Stewart Charlotte Braun: (added character)………….……….Gabbi Reeves Peggy Jean: (added character)………..………….…….Lindsey Daley Woodstock: (added char.)……………………….....…...Taylor Bettles A HUGE Thank You to all who auditioned. You all did a GREAT job! Casting was a difficult decision…….. (that’s one of the reasons we added 11 Characters, basically the rest of the Peanuts gang). We’re excited about the show, it will be a FUN journey for us to embark upon. First rehearsal will be after Christmas break, January 12th in Rm. I-03 @ 3:10 - 5:30 pm. Scripts and a detailed calendar and music -

Character Guide

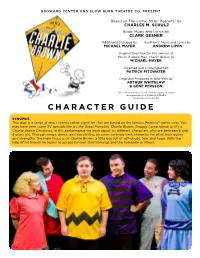

BROWARD CENTER AND SLOW BURN THEATRE CO. PRESENT Based on The Comic Strip “Peanuts” by CHARLES M. SCHULZ Book, Music and Lyrics by CLARK GESNER Additional Dialogue by Additional Music and Lyrics by MICHAEL MAYER ANDREW LIPPA Original Direction for this version of You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown by MICHAEL MAYER Directed and Choreographed PATRICK FITZWATER Originally Produced in New York by ARTHUR WHITELAW & GENE PERSSON You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown is presented by arrangement with TAMS-WITMARK www.tamswitmark.com CHARACTER GUIDE SYNOPSIS This play is a series of short scenes called vignettes that are based on the famous Peanuts© comic strip. You may have seen some TV specials like It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown; Snoopy Come Home; or It’s a Charlie Brown Christmas. In this performance we learn about six different characters who are between 6 and 8 years old. Through songs, dance, and storytelling we come to know each character for all of their quirks and strengths. The main focus is on Charlie Brown, a little boy full of self-doubt, fear, and hope. With the help of his friends he learns to accept his own shortcomings and the humanity in others. CHARLIE BROWN is the LUCY VAN PELT often plays SNOOPY is Charlie Brown’s main character of this story the role of therapist to her dog, but he usually forgets that and is everyone’s favorite classmates. Mostly, she has lots and acts like a human. He is a “blockhead.” He has trouble of opinions and tends to boss beagle who is loyal, funny and flying kites and playing sports, others around. -

You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown

You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown Special Thanks Book by John Gordon to these folks who donated time, talent and/or Music and Lyrics by Clark Gesner materials for the show! Additional music and lyrics by Andrew Lippa and dialogue by Michael Mayer Rising Star Theatre Company YOU’RE A GOOD MAN, CHARLIE BROWN Steve Wilke and the good folks at Dubuque Laser & Fabrication is presented by arrangement with: Tams-Witmark Music Library, Inc. Scott Meissen 560 Lexington Avenue, New York, New York 10022 The Staidl Family Jon Fazio and Bel-Aire Rental ACT ONE "Opening" …………………………………………………………………………….Company Very-very–very special thanks to: "You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown"………Charlie Brown and Company Terry Reichel and Jim Lyness and Rob, Karen and Tyler Powers for all of their countless hours on this production! "You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown" (reprise) We could not have put together this show without you!! …………………………………………………………….Charlie Brown, Linus, and Sally "Schroeder" …………..Lucy (sung over Beethoven's "Moonlight Sonata") Even MORE Thanks! "Snoopy"………………………………………………………………………………….Snoopy Thanks to the Wahlert Catholic High School community for supporting "My Blanket and Me" ……………………………………………Linus and Company the arts—in particular Ron Myers. Also—thanks to Tom English and Molly Pilcher for coordinating gym schedules. "The Kite"………………………………………………………………………Charlie Brown A special thanks to Jenny Spahn who organized our production week "The Doctor is In"……………..…………………………….Lucy and Charlie Brown dinners as well as the parents who helped with that activity. "Beethoven Day"…………………………………………..Schroeder and Company And Finally... "Rabbit Chasing"………………………………………………………..Sally and Snoopy Thanks for Frank McClain, Tracey Richardson, Michelle Blanchard and the whole team at the Grand Opera House for all of their assistance "The Book Report"………………………………………………………………..Company with this production. -

CHARLIE BROWN – Played As Fourth Grade Male, Audition Age 14-Adult

CHARLIE BROWN – Played as Fourth Grade Male, VIOLET GRAY – Played as a Sixth Grade Female Audition Age 14-Adult, Any Gender 100 lines Audition Age 14-Adult, Any Gender 30 lines SING: The Doctor Is In, The Kite SING: Happiness, You’re A Good Man LUCY VAN PELT - Played as Fourth Grade Female, FREIDA - Played as a Second Grade Female. Audition Age 14-Adult, Any Gender 100 Lines Audition Age 12-Adult, Any Gender 25 lines SING: Schroeder, Little Known Facts SING: Happiness, Good Man SCHROEDER – Played as a Sixth Grade Male, SHERMIE – Played as a Sixth Grade Male, Audition Age 14-Adult, Any Gender 60 lines Audition Age 14-Adult, Any Gender 20 lines SING: Happiness, Beethoven Day SING: Happiness You’re A Good Man SNOOPY – Played as a Dog RERUN – Played as a Kindergarten Male, Audition Age 12-Adult, Any Gender 45 lines Audition Age 10-Adult, Any Gender 20 lines SING: Snoopy, Suppertime SING: Happiness, Good Man SALLY BROWN – Played as a Second Grade Female. PEPPERMINT PATTY – Played as a Fourth Grade Female, Audition Age 12-Adult, Any Gender 45 lines Audition Age 12-Adult, Any Gender 15 lines SING: Happiness, My New Philosophy SING: Happiness, Good Man LINUS VAN PELT – Played as a Second Grade Male, FRANKLIN ARMSTRONG – Played as a Fourth Grade Male Audition Age 12-Adult, Any Gender 45 lines Audition Age 12-Adult, Any Gender 15 lines SING: Happiness, My Blanket and Me SING: Happiness, Good Man MARCIE JOHNSON – Played as a Fourth Grade Female, Audition Age 12-Adult, Any Gender 10 lines SING: Happiness, Good Man WOODSTOCKS (Up to Six) Played as Birds, and Birds playing Ball Players, Waiters, Rabbits, PIG PEN - Played as a Second Grade Male, Audition Age 6-12, Any Gender Audition Age 12-Adult, Any Gender 10 lines SING: Happiness, Good Man Play Kazoo SING: Happiness, Good Man DANCERS (2-6) Played as Kites, Waiters, Rabbits, Blankets, Students, Ball Players, Chorus Line Audition Age 6-Adult, Any Gender DANCE TO: Personal Favorite, My Blanket and Me, The Kite and Suppertime CHARLIE BROWN (Sit) I’m sitting back down. -

Peanuts: Snoopy and Friends Pdf, Epub, Ebook

PEANUTS: SNOOPY AND FRIENDS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jacquie Bloese | 32 pages | 07 May 2015 | Scholastic | 9781910173312 | English | Leamington Spa, United Kingdom Peanuts: Snoopy and Friends PDF Book The series also had a dog that looked much like Snoopy. Only What's Necessary: Charles M. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. You're Not Elected Peanuts is one of the literate strips with philosophical, psychological, and sociological overtones that flourished in the s. Quick View. Back to top. Marcel rated it it was amazing May 11, A collection of comic strips featuring Snoopy, Charlie Brown and the rest of the Peanuts gang. Categories : Peanuts comic strip establishments in the United States disestablishments in the United States American comic strips Gag-a-day comics Satirical comics Slice of life comics Sony Music Entertainment Japan franchises American culture Child characters in comics Comics about dogs comics debuts comics endings Comic strips set in the United States American comics adapted into films Comics adapted into animated series Comics adapted into animated films Comics adapted into television series Comics adapted into video games Comics adapted into plays. It's Magic When Schulz and the syndicate reached a successful agreement, United Media stored these unpublished strips, the existence of which eventually became public. What Have We Learned? Studios has published a series of comic books that feature new material by new writers and artists, although some of it is based on classic Schulz stories from decades past, as well as including some classic strips by Schulz, mostly Sunday color strips. A different name for the comic strip became necessary after legal advice confirmed that Little Folks was a registered trademark. -

Charlie Brown Character Descriptions

YOU’RE A GOOD MAN CHARLIE BROWN CHARACTER INFORMATION Snoopy Snoopy is an extroverted beagle with a Walter Mitty complex. He is a virtuoso at every endeavor- at least in his daydreams atop his doghouse. He regards his master, Charlie Brown, as "that round-headed kid" who brings him his supper dish. He is fearless though prudently cautious about "the cat next door." He never speaks- that would be one human trait too many- but he manages to convey everything necessary in facial expressions and thought balloons. A one-man show with superior intelligence and vivid imagination, he has created such multiple personalities as: Joe Cool, World War I Flying Ace, Literary Ace, Flashbeagle, Vulture, Foreign Legionnaire, etc. Lucy Lucy Van Pelt works hard at being bossy, crabby and selfish. She is loud and yells a lot. Her smiles and motives are rarely pure. She's a know-it-all who dispenses advice whether you want it or not--and for Charlie Brown, there's a charge. She's a fussbudget, in the true sense of the word. She's a real grouch, with only one or two soft spots, and both of them may be Schroeder, who prefers Beethoven. As she sees it, hers is the only way. The absence of logic in her arguments holds a kind of shining lunacy. When it comes to compliments, Lucy only likes receiving them. If she's paying one--or even smiling--she's probably up to something devious . Charlie Brown Charlie Brown wins your heart with his losing ways. It always rains on his parade, his baseball game, and his life. -

Prusaprinters

Linus van Pelt 3D MODEL ONLY reddadsteve VIEW IN BROWSER updated 3. 2. 2019 | published 3. 2. 2019 Summary Linus van Pelt, from the comic strip Peanuts by Charles Schulz. Linus is the best friend of Charlie Brown and is also the younger brother of Lucy van Pelt. Though young, Linus is very intelligent and very wise, and acts as the strip's philosopher and theologian. The model is in proportion to my other Peanuts models. No supports are required. If you have the proper filament colors, no painting is needed. Don't let the number of pieces or my lengthy notes worry you, it's a reasonably quick print and very, very easy to assemble. The model is 140mm tall. Enjoy! Toys & Games > Action Figures & Statues comics peanuts catoon Rafts: Doesn't Matter Supports: No Resolution: .2mm Infill: 10% Notes: See below for helpful printing and assembly tips. Building the model Colors (there are no multiple printed pieces) Black: hair eyes mouth eyebrows pants shirt_black_1 shirt_black_2 shirt_black_3 shirt_black_4 shirt_black_5 shirt_black_6 shirt_black_7 shirt_black_8 shirt_black_9 shirt_black_10 .. Beige or Flesh: head_top head_bottom arm_left arm_right legs .. Brown: shoes .. Light Blue: blanket .. Red: socks shirt_red_1 shirt_red_2 shirt_red_3 shirt_red_4 shirt_red_5 shirt_red_6 shirt_red_7 shirt_red_8 shirt_red_9 shirt_red_10 shirt_red_11 .. Any color (hidden pieces) head_pins shirt_pin Printing and assembly tips Printing tips 1-As with most of my models, no supports are required. 2-The arms are tall with a small base, so I used a brim on those two pieces. 3-Be sure to clean any first layer squish if you have any problem joining parts. The parts should fit nicely when printed cleanly or with a slight first layer squish. -

In the Essence of the Gourd

Booth Volume 6 Issue 3 Article 2 3-14-2014 In the Essence of the Gourd Ian Golding Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/booth Recommended Citation Golding, Ian (2014) "In the Essence of the Gourd," Booth: Vol. 6 : Iss. 3 , Article 2. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/booth/vol6/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Booth by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In the Essence of the Gourd Abstract Linus had relished the quiet times when Charlie left to scavenge for copper. Alone, he’d squat on his blue blanket beside the enormous pumpkin and whisper into the stem just how much he loved it. For hours he’d lean close, brushing his lips against the orange flesh, and discuss whatever came to mind—Giant Pumpkin growing season, Giant Pumpkin growing tips, Giant Pumpkin growing records. Keywords Peanuts, the Great Pumpkin, Linus van Pelt, Charlie Brown Cover Page Footnote "In the Essence of the Gourd" was originally published at Booth. This article is available in Booth: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/booth/vol6/iss3/2 Golding: In the Essence of the Gourd ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! March 14,! 2014! In the Essence of the Gourd ! Fiction by Ian Golding ! Linus had relished the quiet times when Charlie left to scavenge for copper. Alone, he’d squat on his blue blanket beside the enormous pumpkin and whisper into the stem just how much he loved it. -

PDF Download Be My Valentine, Charlie Brown Kindle

BE MY VALENTINE, CHARLIE BROWN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Charles M. Schulz | 128 pages | 03 Jan 2008 | Running Press | 9780762427543 | English | Philadelphia, United States Be My Valentine, Charlie Brown PDF Book Let me count the ways. Sign In. The next day, Violet gives Charlie Brown a used valentine she struck her own name from it as an apology, despite Schroeder berating her for dropping by the day after Valentine's Day and acting out of guilt. Charlie Brown : Thank you. Sally Brown voice Linda Ercoli I would give him a Valentines Day Card! It's Valentine's Day again and Charlie Brown dreams the seemingly hopeless dream to receiving a valentine from anyone. Schulz written and created by. Charlie Brown : Don't listen to him! Schulz written and created by. Want to Read saving…. Taglines: Fall in love with Peanuts! Sally wants to make one for Linus. I love thee to the depth and breadth and height my soul can reach, when feeling out of sight for the ends of being and ideal grace. Alternate Versions. Keep track of everything you watch; tell your friends. Schulz Written by Charles M. Snoopy in Space. I love thee freely as men strive for night; I love thee purely as they turn from praise; I love thee passion put to use in my old griefs and my childhood's faith. Someday You'll Find Her Linus van Pelt voice. Who do you think you are? I love thee with the breath, smiles, tears of all my life! The program's theme song, "Heartburn Waltz" Track 15 is performed in ten different variations. -

Charlie Brown the Musical Ba5ep on the Comic Strip "Peanuts" Bv Charles M

SLOC Schenectady Light Opera Company Musical Theater Youth Theater Presents VOU'RE A GOOP MAN, CHARLIE BROWN THE MUSICAL BA5EP ON THE COMIC STRIP "PEANUTS" BV CHARLES M. 5CHULZ BOOK, MUSIC ANP LYRICS BY CLARK GESNER SPtLLIHGBtt Guys and Caroline, The 25th Annual Young Putnam County Dolls or Change Spelling Bee Frankenstein Oct 11-20, 2013 Feb 7-16, 2014 March 21-30, 2014 May 9-18, 2014 Presented at 427 Franklin Street, Schenectady • 877-350-7378 • www.sloctheater.org Mill ifilWSI ervice 525--'=-:r:::- ,. a coup^® °^^^ttistio.co«^ ' "Si I ^ 'JXVo — <in0 mafc/no V descrih- P^rfe T® Was Wf.// ;r:, ®'^'"ce w^c .... .. ,r===sssife^ fl y. _ ^^ow" ®^8;374_7Sr'^-2niiJes,friiive <? '^" mazzone Our Patrons Producer f2,500 or More) First National Bank of Scotia Musical Director (^500-^1,000) Laurie & David Bacheldor Thomas & Cheryl Delia Sala (33) Nell Burrows Michael Glover (21) Assistant Director (®250-$499) Paige Gauvreau Bill Hickman (In memory of Art)(38) (In memory of Fulvia Hickman)(25) Delia R. Oilman (40) Timothy Murphy Rev. Lisa & David VanderWal Chorlographhr (*100-^249) Joe & Mary Ann Goncra (26) Carol & Ed Osterhout (18) Mr. & Mrs. Robert C. Farquharson (35) Gioia Ottaviano (53) Clark & Millie Gittinger (II) Orlando & Eleaner Pigliavento (49) Bruce & Marty Holden (17) Brett & Sandra Putnam Bradley Johnson (6) John Samatulski & Zakhar Berkovith Bill & Gina Kornrumpf(19) Richard Schoettler Mary & Steve Kozlowski Vern & June Scoville (16) Richard J. Lenehan (10) Dale & Nancy Ellen Swann (40) Elizabeth & John Mowry (5) Charles & Janet Weick (II) Wayne Nelson Statistical Consulting Harald & Joyce Witting (18) Mr. Robert M.