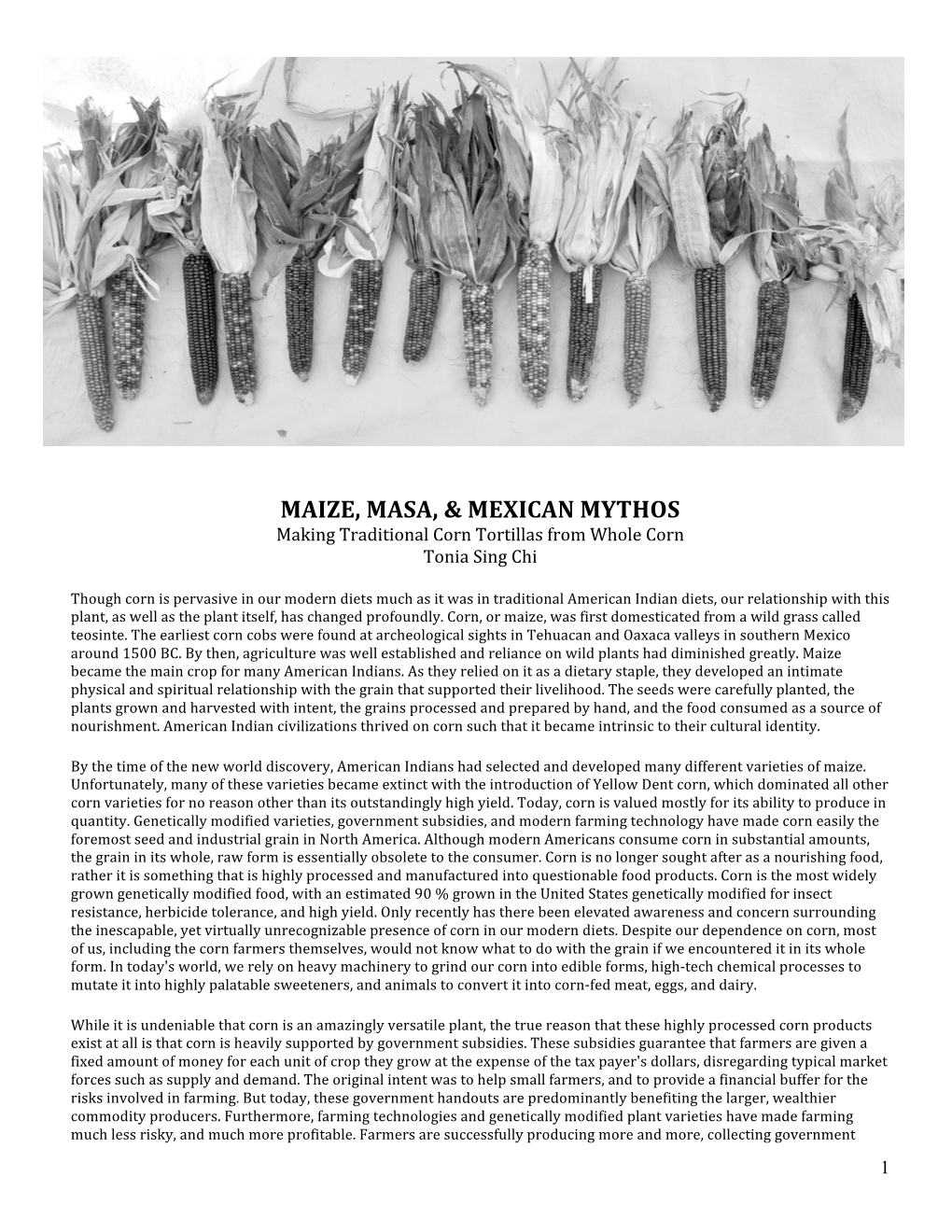

Maize, Masa, & Mexican Mythos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Races of Maize in Bolivia

RACES OF MAIZE IN BOLIVIA Ricardo Ramírez E. David H. Timothy Efraín DÍaz B. U. J. Grant in collaboration with G. Edward Nicholson Edgar Anderson William L. Brown NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Publication 747 Funds were provided for publication by a contract between the National Academythis of Sciences -National Research Council and The Institute of Inter-American Affairs of the International Cooperation Administration. The grant was made the of the Committee on Preservation of Indigenousfor Strainswork of Maize, under the Agricultural Board, a part of the Division of Biology and Agriculture of the National Academy of Sciences - National Research Council. RACES OF MAIZE IN BOLIVIA Ricardo Ramírez E., David H. Timothy, Efraín Díaz B., and U. J. Grant in collaboration with G. Edward Nicholson Calle, Edgar Anderson, and William L. Brown Publication 747 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Washington, D. C. 1960 COMMITTEE ON PRESERVATION OF INDIGENOUS STRAINS OF MAIZE OF THE AGRICULTURAL BOARD DIVISIONOF BIOLOGYAND AGRICULTURE NATIONALACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONALRESEARCH COUNCIL Ralph E. Cleland, Chairman J. Allen Clark, Executive Secretary Edgar Anderson Claud L. Horn Paul C. Mangelsdorf William L. Brown Merle T. Jenkins G. H. Stringfield C. O. Erlanson George F. Sprague Other publications in this series: RACES OF MAIZE IN CUBA William H. Hatheway NAS -NRC Publication 453 I957 Price $1.50 RACES OF MAIZE IN COLOMBIA M. Roberts, U. J. Grant, Ricardo Ramírez E., L. W. H. Hatheway, and D. L. Smith in collaboration with Paul C. Mangelsdorf NAS-NRC Publication 510 1957 Price $1.50 RACES OF MAIZE IN CENTRAL AMERICA E. -

Races of Maize in Brazil and Other Eastern South American Countries

RACES OF MAIZE IN BRAZIL AND OTHER EASTERN SOUTH AMERICAN COUNTRIES F. G Brieger J. T. A. Gurgel E. Paterniani A. Blumenschein M. R. Alleoni NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Publication 593 Funds were provided for this publication by a contract between the National Academy of Sciences -National Research Council and The Institute of Inter-American Affairs of the International Cooperation Administration. The grant was made for the work of the Committee on Preservation of Indigenous Strains of Maize, under the Agricultural Board, a part of the Division of Biology and Agriculture of the National Academy of Sciences - National Research Council. RACES OF MAIZE IN BRAZIL AND OTHER EASTERN SOUTH AMERICAN COUNTRIES F. G. Brieger, J. T. A. Gurgel, E. Paterniani, A. Blumenschein, and M. R. Alleoni Publication 593 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Washington, D. C. 1958 COMMITTEE ON PRESERVATION OF INDIGENOUS STRAINS OF MAIZE OF THE AGRICULTURAL BOARD DIVISIONOF BIOLOGYAND AGRICULTURE NATIONALACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONALRESEARCH COUNCIL Ralph E. Cleland, Chairman J. Allen Clark, Executive Secretary Edgar Anderson Claud L. Horn Paul C. Mangelsdorf William L. Brown Merle T. Jenkins G. H. Stringfield C. O. Erlanson George F. Sprague Other publications in this series: RACES OF MAIZE IN CUBA William H. Hatheway NAS - NRC Publication 4.53 I957 Price $1.50 RACES OF MAIZE IN COLOMBIA L. M. Roberts, U. J. Grant, Ricardo Ramirez E., W. H. Hatheway, and D. L. Smith in collaboration with Paul C. Mangelsdorf NAS-NRC Publication 510 1957 Price $1.50 RACES OF MAIZE IN CENTRAL AMERICA E. J. Wellhausen, Alejandro Fuedes O., and Antonio Hernandez Corzo in collaboration with Paul C. -

Ecosystems and Agro-Biodiversity Across Small and Large-Scale Maize Production Systems, Feeder Study to the “TEEB for Agriculture and Food”

Ecosystems and agro-biodiversity across small and large-scale maize production systems, feeder study to the “TEEB for Agriculture and Food” i Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge TEEB and the Global Alliance for the Future of Food on supporting this project. We would also like to acknowledge the technical expertise provided by CONABIO´s network of experts outside and inside the institution and the knowledge gained through many years of hard and very robust scientific work of the Mexican research community (and beyond) tightly linked to maize genetic diversity resources. Finally we would specially like to thank the small-scale maize men and women farmers who through time and space have given us the opportunity of benefiting from the biological, genetic and cultural resources they care for. Certification All activities by Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, acting in administrative matters through Nacional Financiera Fideicomiso Fondo para la Biodiversidad (“CONABIO/FFB”) were and are consistent under the Internal Revenue Code Sections 501 (c)(3) and 509(a)(1), (2) or (3). If any lobbying was conducted by CONABIO/FFB (whether or not discussed in this report), CONABIO/FFB complied with the applicable limits of Internal Revenue Code Sections 501(c)(3) and/or 501(h) and 4911. CONABIO/FFB warrants that it is in full compliance with its Grant Agreement with the New venture Fund, dated May 15, 2015, and that, if the grant was subject to any restrictions, all such restrictions were observed. How to cite: CONABIO. 2017. Ecosystems and agro-biodiversity across small and large-scale maize production systems, feeder study to the “TEEB for Agriculture and Food”. -

Three Sisters Garden One of the Best Ways to Get Children Interested in History Is to Bring It Into the Present

Three Sisters Garden One of the best ways to get children interested in history is to bring it into the present. When teaching children about Native Americans in U.S. history, an excellent project is to grow the three Native American sisters, beans, corn and squash. When you plant a three sisters garden, you help to bring an ancient culture to life. Let’s look at growing corn with squash and beans. The story of the three Native American sisters The three sisters way of planting originated with the Haudenosaunee tribe. The story goes that beans corn and squash are actually three Native American maidens. The three, while very different, love each other very much and thrive when they are near each other. It is for this reason that the Native Americans plant the three sisters together. Tips on how to plant a three sisters garden First, decide on a location. Like most vegetable gardens, the three Native American sisters garden will need direct sun for most of the day and a location that drains well. Next, decide on which plants you will be planting. While the general guideline is beans, corn and squash, exactly what kind of beans, corn and squash you plant is up to you. For the beans, you will need a pole bean variety. Bush can be used, but pole beans are more true to the spirit of the project. Some good varieties are Kentucky Wonder, Romano Italian and Blue Lake beans. The corn will need to be a tall, sturdy variety. You do not want to use a miniature variety. -

TASTES from HOME Recipes from the Refugee Community PREFACE

TASTES FROM HOME Recipes from the Refugee Community PREFACE In writing the articles for this cookbook, I had the privilege and pleasure of speaking with refugees from all over the world who now call Canada home. Sometimes we had the good fortune of meeting in person, but because this project originated during the 2020 pandemic, often we spoke over the phone or through a video call, each of us holed up in our homes. They shared their stories, and they shared their recipes. From one foodie to another, the excitement and pride each person felt about their recipes was palpable. For many, the recipes hold a personal connection to a family member or to a memory, and the food is an indisputable connection to their culture. Each person has a unique story, with different outlooks, challenges, and rewards, but I was struck by one thing they all had in common—a desire to give back to Canada. From the Mexican restaurant owner who plans to employ dozens of Canadians, to the Syrian entrepreneur who donated the proceeds from his chocolate factory to Canadians impacted by wildfires, to the former Governor General who became a figurehead for the country, each person expressed profound gratitude and an eagerness to help the country that took them in. We often hear about refugees in abstract faraway terms, through statistics about the number of people fleeing from one country to another, but in speaking with these 14 people those statistics became humanized and the abstract became real experiences. Their stories are captivating, their recipes are mouthwatering, and I hope you enjoy both in the following pages. -

Effect of Alkaline Soaking and Cooking on the Proximate, Functional and Some Anti-Nutritional Properties of Sorghum Flour

AU J.T. 14(3): 210-216 (Jan. 2011) Effect of Alkaline Soaking and Cooking on the Proximate, Functional and Some Anti-Nutritional Properties of Sorghum Flour Ocheme Ocheme Boniface and Mikailu Esther Gladys Food Science and Nutrition Department, Federal University of Technology Minna, Nigeria E-mail: <[email protected]; [email protected]> Abstract The effect of nixtamalization on the functional, proximate, and anti-nutritional properties of sorghum flour was studied. Flour samples were produced from soaked sorghum grains and cooked sorghum grains. A portion of sorghum grains were soaked in water and 1% lime solution for 24 hours and some were cooked for 30 minutes in both water and 1% lime solution. At the end of soaking and cooking, the grains were sundried; milled; sieved with a 0.25 mesh screen; and packaged. Alkaline cooking of sorghum resulted in flour with significantly higher protein; water and oil absorption capacity; pH; hygroscopicity; phytate and trypsin inhibitor and significantly lower ash; tannins and cyanide content than flours from untreated and water treated sorghums, while alkaline soaking resulted in flour with significantly higher carbohydrate; water and oil absorption capacity; and pH and significantly lower packed bulk density and hydrogen cyanide than flours from untreated and water treated sorghum. Keywords: Nixtamalization, functional properties, anti-nutritional properties, soaking, cooking. Introduction Unleavened bread (tortilla) is a common food in central and South America produced from Nixtamalization refers to a process of sorghum cooked in lime solution (Asiedu preparing maize (corn) in which the grain is 1989). In nixtamalization, dried cereal grains cooked and soaked in alkaline solution, usually are cooked in an alkaline solution at or near its lime solution, and then dehulled (Ocheme et al. -

Corn Has Diverse Uses and Can Be Transformed Into Varied Products

Maize Based Products Compiled and Edited by Dr Shruti Sethi, Principal Scientist & Dr. S. K. Jha, Principal Scientist & Professor Division of Food Science and Postharvest Technology ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, Pusa New Delhi 110012 Maize is also known as Corn or Makka in Hindi. It is one of the most versatile crops having adaptability under varied agro-climatic conditions. Globally, it is known as queen of cereals due to its highest genetic yield potential among the cereals. In India, Maize is grown throughout the year. It is predominantly a kharif crop with 85 per cent of the area under cultivation in the season. The United States of America (USA) is the largest producer of maize contributing about 36% of the total production. Production of maize ranks third in the country after rice and wheat. About 26 million tonnes corn was produced in 2016-17 from 9.6 Mha area. The country exported 3,70,066.11 MT of maize to the world for the worth of Rs. 1,019.29 crores/ 142.76 USD Millions in 2019-20. Major export destinations included Nepal, Bangladesh Pr, Myanmar, Pakistan Ir, Bhutan The corn kernel has highest energy density (365 kcal/100 g) among the cereals and also contains vitamins namely, vitamin B1 (thiamine), B2 (niacin), B3 (riboflavin), B5 (pantothenic acid) and B6. Although maize kernels contain many macro and micronutrients necessary for human metabolic needs, normal corn is inherently deficient in two essential amino acids, viz lysine and tryptophan. Maize is staple food for human being and quality feed for animals. -

Different Types of Corn There a Various Types of Corn and They All Have Different Purposes and Distinguished Traits

Different Types of Corn There a various types of corn and they all have different purposes and distinguished traits. Read about the 5 different types of corn and write a 5 paragraph essay on what type of corn you would want to grow. Make sure you do your research! Dent Corn: This type of corn is often used for livestock feeds, industrial products, and as well as used to make processed foods. Another name for dent corn is “Field Corn”. This type of corn is mostly grown in the United States. This corn is a mix of hard and soft starches that become indented when the corn dries out. Flint Corn: Also known as “Indian Corn” is very similar to Dent Corn. They have primarily the same purpose as dent corn, but in the United States its main purpose is decoration. Flint Corn is primarily grown in Central and South America. It has a hard outer shell and the kernels are a variety of colors from red to white. Popcorn: Popcorn is a type of Flint Corn, although it has it has different size, shape, starch level, and moisture content. It has a soft starchy center surrounded by a very hard exterior shell. When popcorn is heated, the natural moisture inside the shell turns into steam and builds up enough pressure until it explodes. Sweet Corn: Also known as “corn on the cob”. This type of corn you will find at your summer BBQ’s and you love to enjoy it with a burger on a hot summer day. This type of corn can be canned or frozen for future consumption. -

Stone-Boiling Maize with Limestone: Experimental Results and Implications for Nutrition Among SE Utah Preceramic Groups Emily C

Agronomy Publications Agronomy 1-2013 Stone-boiling maize with limestone: experimental results and implications for nutrition among SE Utah preceramic groups Emily C. Ellwood Archaeological Investigations Northwest, Inc. M. Paul Scott United States Department of Agriculture, [email protected] William D. Lipe Washington State University R. G. Matson University of British Columbia John G. Jones WFoasllohinwgt thion Sst atnde U naiddveritsitiony al works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/agron_pubs Part of the Agricultural Science Commons, Agronomy and Crop Sciences Commons, Food Science Commons, and the Indigenous Studies Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ agron_pubs/172. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Agronomy at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Agronomy Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (2013) 35e44 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jas Stone-boiling maize with limestone: experimental results and implications for nutrition among SE Utah preceramic groups Emily C. Ellwood a, M. Paul Scott b, William D. Lipe c,*, R.G. Matson d, John G. Jones c a Archaeological -

Corn Tortillas from Homemade Masa

Curriculum for Restoration Restorationpedagogy.com/curriculum CORN TORTILLAS FROM HOMEMADE MASA MATERIALS 2 lbs. of dried corn or grain corn on cob. Preferably Zapatista Corn. Until harvest the Mexican grocer in Toppenish has dried corn. 2 tablespoons of Cal Mexicana lime (Calcium Hydroxide / Powdered Lime) (Available at Mexican grocer in Toppenish) ~2 pounds of prepared Masa (making masa takes over night so the kids will reach a point where you magically fast forward for them) Mortar and pestle Plate Grinder, Food Processor, or other grinding tool that can handle wet ingredients Tortilla press or a pie dish and heavy pan Plastic to keep tortillas from sticking – cut freezer bags work great Griddle or frying pan to cook tortillas OBJECTIVES Prepare and sample tortillas, from scratch Gain respect and understanding of Indigenous and Hispanic cultures of Mexico BACKGROUND Background info should be covered in preceding lesson ‘The Story of Corn.’ If this is being taught as a standalone lesson condense ‘The Story of Corn’ into an introduction for this lesson. INTRODUCTION 1. Who likes tortillas? How often do you eat them? With what meals? Etc. (get thinking and talking about tortillas. a. Ask students if they have ever made tortillas, or if anyone in their family does and how. b. Does anyone know how they are made? 2. The word ‘tortilla’ comes from the Spanish word “torta” which is loosely translated as bread or cake. When you add an “‐illa” to a word it means small or little. So, a torta‐illa is a small or little bread. a. The Spanish colonizers arrived and named this food in their own language, but Native peoples’ had their own names, in their own languages for tortillas. -

Crediting Coconut, Hominy, Corn Masa, and Masa Harina in the Cnps

2 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, SE, Suite 754, East Tower, Atlanta, GA 30334 (404) 656-5957 Brian P. Kemp Amy M. Jacobs Governor Commissioner MEMORANDUM To: Institutions and Sponsors Participating in the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) and the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) From: Sonja R. Adams, Director of Provider Services – Nutrition (Original Signed) Date: September 13, 2019 (v.2) Subject: Crediting Coconut, Hominy, Corn Masa, and Masa Harina in the CNPs Legal Authority: USDA Policy Memorandum SP-34-2019, CACFP 15-2019, SFSP 15-2019, August 22, 2019 (rescinding SP 22-2019, CACFP 09-2019, SFSP 08-2019, Crediting Coconut, Hominy, Corn Masa, and Corn Flour in the CNPs, April 17, 2019; SP 02-2013, Corn Masa (Dough) for Use in Tortilla Chips, Taco Shells, and Tamales, October 3, 2012; and TA 01-2008, Crediting of Corn Meal (Cornmeal) and Corn Flour for Grains/Breads Component, December 11, 2007). Cross Reference/ See also: DECAL Policy Memorandum, Update of Food Crediting System to Include Various Food Items Which Were Previously Uncreditable, December 28, 2018. This policy memorandum rescinds and replaces DECAL Policy Memorandum, Crediting Coconut, Hominy, Corn Masa, and Corn Flour in the CNPs, May 17, 2019. As stated above, this memorandum rescinds and replaces DECAL Policy Memorandum, Crediting Coconut, Hominy, Corn Masa, and Corn Flour in the CNPs, May 17, 2019 which was based on expanded Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) policy guidance originally released on December 4, 2018. 1 Such guidance sought to inform participating institutions and sponsors of the credibility of various food items which were previously uncreditable. -

Limited Lunch Menu

Feed the Heart Quench the Soul LIMITED LUNCH MENU SOUTHTOWN CURBSIDE, CARRYOUT & DINE IN ANTOJITOS LUNCH SPECIALS Fire Roasted Salsa & Chips 3.95 Daily lunch specials served with rice, beans and choice of 2 corn or flour tortillas, unless otherwise noted. Bean & Cheese Nachos Served with jalapeño peppers. 7.25 Lisa’s Special Two cheese enchiladas with your choice of beef or chicken fajitas and guacamole. 8.95 Nachos Estilo Rosario’s Topped with shredded chicken, Monterey Jack cheese and crema fresca. 7.95 Fajita Plate Chicken or beef fajitas served with guacamole and frijoles a la charra. 8.95 Queso Flameado Queso asadero, grilled onions & peppers plus your choice of chorizo or hongos guisados. Lengua Plate Served with housemade tortillas. 8.25 Tender tips of beef tongue delicately seasoned and simmered in a light tomato sauce. 8.95 Puffy Taco Plate Albóndigas Your choice of beef, chicken or guacamole. 8.25 Mexican meatballs made with a combination of ground beef, pork and herbs. Braised in a rich and spicy broth. 7.95 Carne de Puerco en Chile Cascabel Tender pork tips in a chile cascabel sauce. 8.25 Angelica’s Ceviche Fino Delicate white fish, red onions and jalapeño peppers marinated in fresh lime juice & tossed in an Flauta Plate oregano vinaigrette. Served w/ avocado, cilantro & tostadas. 8.95 Three chicken flautas topped with guacamole & crema fresca. Served with frijoles a la charra. 8.25 Guacamole & House-made Tostadas 8.95 Enchiladas de Mole Two chicken-filled enchiladas topped with our peanut mole sauce and Monterey Jack cheese. 8.25 Queso Rosario’s Enchiladas Verdes de Pollo y Elote Chihuahua style creamy cheese dip served with tostadas.