Higher Defence Management in India: Need for Urgent Reappraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume Xlv, No. 3 September, 1999 the Journal of Parliamentary Information

VOLUME XLV, NO. 3 SEPTEMBER, 1999 THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOL. XLV NO.3 SEPTEMBER 1999 CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL NOTE 281 SHORT NOTES The Thirteenth Lok Sabha; Another Commitment to Democratic Values -LARRDIS 285 The Election of the Speaker of the Thirteenth Lok Sabha -LARRDIS 291 The Election of the Deputy Speaker of the Thirteenth Lok Sabha -LARRDIS 299 Dr. (Smt.) Najma Heptulla-the First Woman President of the Inter-Parliamentary Union -LARRDIS 308 Parliamentary Committee System in Bangladesh -LARRDIS 317 Summary of the Report of the Ethics Committee, Andhra Pradesh Legislative Assembly on Code of Conduct for Legislators in and outside the Legislature 324 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES Conferences and Symposia 334 Birth Anniversaries of National Leaders 336 Indian Parliamentary Delegations Going Abroad 337 Bureau of Parliamentary Studies and Training 337 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 339 SESSIONAl REVIEW State Legislatures 348 SUMMARIES OF BooKS Mahajan, Gurpreet, Identities and Rights-Aspects of Liberal Democracy in India 351 Khanna, S.K., Crisis of Indian Democracy 354 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 358 ApPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Fourth Session of the Twelfth lok Sabha 372 II. Statement showing the work transacted during the One Hundred and Eighty-sixth Session of the Rajya Sabha 375 III. Statement showing the activities of the legislatures of the States and the Union territories during the period 1 April to 30 June 1999 380 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament and assented to by the President during the period 1 April to 30 June 1999 388 V. -

India's Nuclear Odyssey

India’s Nuclear Odyssey India’s Nuclear Andrew B. Kennedy Odyssey Implicit Umbrellas, Diplomatic Disappointments, and the Bomb India’s search for secu- rity in the nuclear age is a complex story, rivaling Odysseus’s fabled journey in its myriad misadventures and breakthroughs. Little wonder, then, that it has received so much scholarly attention. In the 1970s and 1980s, scholars focused on the development of India’s nuclear “option” and asked whether New Delhi would ever seek to exercise it.1 After 1990, attention turned to India’s emerg- ing, but still hidden, nuclear arsenal.2 Since 1998, India’s decision to become an overt nuclear power has ushered in a new wave of scholarship on India’s nu- clear history and its dramatic breakthrough.3 In addition, scholars now ask whether India’s and Pakistan’s acquisition of nuclear weapons has stabilized or destabilized South Asia.4 Despite all the attention, it remains difªcult to explain why India merely Andrew B. Kennedy is Lecturer in Policy and Governance at the Crawford School of Economics and Gov- ernment at the Australian National University. He is the author of The International Ambitions of Mao and Nehru: National Efªcacy Beliefs and the Making of Foreign Policy, which is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press. The author gratefully acknowledges comments and criticism on earlier versions of this article from Sumit Ganguly, Alexander Liebman, Tanvi Madan, Vipin Narang, Srinath Raghavan, and the anonymous reviewers for International Security. He also wishes to thank all of the Indian ofªcials who agreed to be interviewed for this article. -

Indian Forces (Defence) – May 2019

Indian Forces (Defence) India's military spending up by 3.1% in 2018 Worldwide, military expenditure rose by 2.6% from 2017 to reach $1.8 trillion in 2018, according to SIPRI data. India's spending rose by 3.1%, while Pakistan's military spending rose by 11%. The five biggest spenders were the U.S., China, Saudi Arabia, India and France. IAF carries out first-of-its-kind operation ‘eastern neighbour The Indian Air Force has focussed on air defence preparedness in the eastern and north-eastern sector with an eye on the country’s ‘eastern neighbour'. IAF carried out a drill of its Sukhoi Su-30 jets from the civilian airport on the outskirts of Guwahati. It was the first-of-its-kind operation, also conducted in Kolkata and Durgapur in West Bengal. Launch of Fourth Scorpene Class Submarine - VELA Vela, the fourth Scorpene class submarine being constructed by Mazagon Dock Shipbuilders Limited for the Indian Navy, was launched. This event reaffirms the steps taken by MDL in the ongoing ‘Make In India’ programme, which is being actively implemented by the Department of Defence Production (MoD). INS Ranjit gets decommissioned upon completion of 36 years INS Ranjit, a Rajput class destroyer was decommissioned at a solemn yet grand ceremony at Naval Dockyard, Visakhapatnam culminating a glorious era on 06 May 19.The ship commissioned on 15 September 1983 by Captain Vishnu Bhagwat in erstwhile USSR has rendered yeoman service to the nation for 36 years. DRDO Successfully Conducts Flight Test of ABHYAS Indian Forces (Defence) – May 2019 Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) conducted successful flight test of ABHYAS - High-speed Expendable Aerial Target (HEAT) from Interim Test Range, Chandipur in Odisha. -

EPRS, India's Armed Forces

At a glance November 2015 India's armed forces – An overview India has the world's third-largest armed forces in terms of personnel numbers. However, although India was also the seventh-biggest spender on military equipment in 2014, the country has a problem of deficiency in equipment. India's defence procurement is still dominated by imports, as the domestic industry is handicapped by inefficiency. New Delhi is thus the world's largest importer of military equipment. Attempts in the past to reform the national security system have also failed. Attempts to reform India's armed forces and security policy The Commander-in-Chief of India's armed forces is President Pranab Mukherjee. India lacks a Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) and this, along with the lack of a National Security Strategy, has been pointed out as one of the shortcomings in the country's security. The creation of a CDS is a much-delayed reform, recommended by the Group of Ministers (GOM) report on 'Reforming the National Security System' back in February 2001. A consultation process for the creation of this post is taking place but may meet internal resistance, while analysts argue that politicians have shown little interest on the issue. A Chief of Integrated Defence Staff post has been created following the GOM report; however the holder has no voting power in the frame of the Chiefs of Staff Committee which gathers together the chiefs of the three branches of the Armed Forces (Chief of the Army Staff, Chief of the Naval Staff, Chief of the Air Staff) and advises the Minister of Defence. -

Defence, Science & Technology Current Affairs

www.gradeup.co Defence, Science & Technology Current Affairs 1. Tech Mahindra announced its biggest defence order worth over Rs 300 crore with the Indian Navy. Note: As part of the ‘Armed Forces Secure Access Card’ (AFSAC) Project, Tech Mahindra will implement RFID (Radio Frequency Identification) based Access Control System across all naval bases and ships. The new AFSAC Card will replace the existing paper-based Identity Card for all Navy personnel including dependents and ex-servicemen. Using the CMMI (Capability Maturity Model Integration) level 5 processes, Tech Mahindra will develop a secure application to manage the access control devices, network devices and the AFSAC Card through a data centre. 2. Vice Admiral Karambir Singh (Commander-in-Chief of the Eastern Naval Command) has taken over as the 24th Navy Chief. Note: Navy Chief Admiral Sunil Lanba has retired on completion of his tenure. During his tenure as the Chief of Naval Staff, Admiral Lanba set the tone for several transitions in operational, training and organizational philosophy of the Indian Navy. 1. Kolkata-based defence shipyard signed an Rs. 6,311-crore contract with the Defence Ministry to build eight anti-submarine warfare shallow watercraft for the Indian Navy – Garden Reach Shipbuilders & Engineers. Note: The first vessel will be delivered within 42 months from the contract (by October 2022).The ASWSWCs are equipped with sophisticated sonar, with an algorithm that differentiates the signals reflected off the enemy submarine from those bouncing off the sea bed.These vessels will also have the ability to sprint fast for short bursts order to maintain contact with a submarine.After that, GRSE must deliver two more ASWSWCs annually, completing delivery by April 2026. -

Parliamentary Bulletin

RAJYA SABHA Parliamentary Bulletin PART - I (TWO HUNDRED AND TWENTIETH SESSION) No. 4862 FRIDAY, AUGUST 20, 2010 Brief Record of the Proceedings of the Meeting of the Rajya Sabha held on the 20th August, 2010 11-00 a.m. 1. Starred Questions Starred Question Nos. 381 to 387 were orally answered. Answers to remaining questions (388 to 400) were laid on the Table. 2. Unstarred Questions Answers to Unstarred Question Nos. 2881 to 3035 were laid on the Table. *12-07 p.m. 3. Papers Laid on the Table The following papers were laid on the Table:— 1. A copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers, under sub-section (1) of Section 7 of the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, 2003: — (i) Statement on Quarterly Review of the trends in receipts and expenditure in relation to the Budget for the third quarter of the financial year 2009-10. (ii) Statement on Quarterly Review of the trends in receipts and expenditure in relation to the Budget at the end of the financial year 2009-10. * From 12-00 Noon to 12-07 p.m. some points were raised. 31505 31506 (iii) Statement on Quarterly Review of the trends in receipts and expenditure in relation to the Budget at the end of the first Quarter of the financial year 2010-11. 2. A copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers:— (i) (a) Tenth Annual Report and Accounts of the Credit Guarantee Fund Trust for Micro and Small Enterprises (CGTMSE), Mumbai, for the year 2009-10, together with the Auditor's Report on the Accounts. -

The Rajya Sabha Met in the Parliament House at 11-00 Am

RAJYA SABHA FRIDAY, THE 20TH AUGUST, 2010 (The Rajya Sabha met in the Parliament House at 11-00 a.m.) 11-00 a.m. 1. Starred Questions The following Starred Questions were orally answered:- Starred Question No. 381 regarding Conversion of fertile land into industrial areas. Starred Question No. 382 regarding Stalling of Delhi bound Shatabdi Express at Bhopal. Starred Question No. 383 regarding Grants to States for SSA. Starred Question No. 384 regarding GPS in Railways. Starred Question No. 385 regarding Khurda-Bolangir railway line. Starred Question No. 386 regarding Train accidents. Starred Question No. 387 regarding Incidence of dacoity in running trains. Answers to remaining Starred Question Nos. 388 to 400 were laid on the Table. 2. Unstarred Questions Answers to Unstarred Question Nos. 2881 to 3035 were laid on the Table. *12-07 p.m. 3. Papers Laid on the Table Shri Namo Narain Meena (Minister of State in the Ministry of Finance) on behalf of Shri Pranab Mukherjee laid on the Table a copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers, under sub-section (1) of Section 7 of the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, 2003: — (i) Statement on Quarterly Review of the trends in receipts and expenditure in relation to the Budget for the third quarter of the financial year 2009-10. (ii) Statement on Quarterly Review of the trends in receipts and expenditure in relation to the Budget at the end of the financial year 2009-10. * From 12-00 Noon to 12-07 p.m. some points were raised. 20TH AUGUST, 2010 (iii) Statement on Quarterly Review of the trends in receipts and expenditure in relation to the Budget at the end of the first Quarter of the financial year 2010-11. -

Rajya Sabha 159

PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA 159 DEPARTMENT-RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON HOME AFFAIRS ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY NINTH REPORT ON THE CITIZENSHIP (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2011 (PRESENTED TO RAJYA SABHA ON 28TH MARCH, 2012) (LAID ON THE TABLE OF LOK SABHA ON 28TH MARCH, 2012) RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI MARCH, 2012/CHAITRA, 1933 (SAKA) 107 Website:http://rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail:[email protected] C.S.(H.A.)-310 PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA DEPARTMENT-RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON HOME AFFAIRS ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY NINTH REPORT ON THE CITIZENSHIP (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2011 (PRESENTED TO RAJYA SABHA ON 28TH MARCH, 2012) (LAID ON THE TABLE OF LOK SABHA ON 28TH MARCH, 2012) RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI MARCH, 2012/CHAITRA, 1933 (SAKA) CONTENTS PAGES 1. COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE ........................................................................................ (i)-(ii) 2. PREFACE ................................................................................................................................. (iii)-(iv) 3. REPORT .................................................................................................................................. 1—25 CHAPTER I : Background of The Bill ....................................................................... 1—4 CHAPTER II : Presentation of The Ministry of Home Affairs ............................... 5—14 CHAPTER III : Consideration of views/suggestions made in the Memoranda receive on the Bill ............................................................................... -

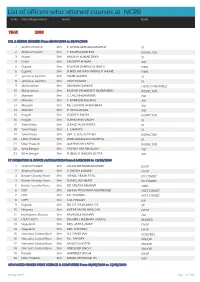

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

PMAY (Urban) Beneficary List

PMAY (Urban) Beneficary List S.no Town Name Father_Name Mobile_No Pres_Address_StreetName 1 Jalesar BABY YASH PAL SINGH 7451085904 MOHALLA AKBARPUR HAVELI, JALESAR ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 2 Jalesar MOHAR SHRI DEVI HAKIM SINGH 8006820002 BHAAMPURI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 3 Jalesar VIPIL KUMAR CHANDARPAL 7534009766 MOHALLA AKABRPUR HAWELI V.P.O JALESAR ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 4 Jalesar GUDDO BEGUM LAL KHAN 9568203120 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 5 Jalesar CHANDRVATI VIJAY SINGH AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 6 Jalesar POONAM BHARATI MIHALLA AKABARPUR 8869865536 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 7 Jalesar SAROJ KUMARI KUWARPAL SINGH 9690823309 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 8 Jalesar MOHAMMAD FAHIM MOHAMMAD SAHID 8272897234 MOHHALA KILA , JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 9 Jalesar SHAJIYA BEGAM BABLU 9758125174 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 10 Jalesar AMIT KUMAR DAU DAYAL BRAMANPURI, JALESAR ETHA UTTAR PREDESH 11 Jalesar KARAN SINGH LEELADHAR BRAMANPURI, JALESAR ETHA UTTAR PREDESH 12 Jalesar GUDDI NAHAR SINGH 9756578025 BRAMANPURI, JALESAR ETHA UTTAR PREDESH 13 Jalesar MADAN MOHAN PURAN SINGH AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 14 Jalesar KANTI MUKESH KUMAR 9027022124 MOHALLA BARHAMAN PURI JALESAR ETHA 15 Jalesar SOMATI DEVI BACHCHO SINGH 7906607313 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 16 Jalesar ANITA DEVI SATYA PRAKESH AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 17 Jalesar VIRENDRA SINGH AMAR SINGH 7500511574 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, -

Mohan India Transformed I-Xx 1-540.Indd

1 The Road to the 1991 Industrial Policy Reforms and Beyond : A Personalized Narrative from the Trenches Rakesh Mohan or those of us beyond the age of fifty, India has been transformed beyond Fwhat we might even have dreamt of before the 1990s. In real terms, the Indian economy is now about five times the size it was in 1991. This, of course, does not match the pace of change that the Chinese economy has recorded, which has grown by a factor of ten over the same period and has acquired the status of a global power. Nonetheless, the image of India, and its own self-image, has changed from one of a poverty-ridden, slow-growing, closed economy to that of a fast-growing, open, dynamic one. Though much of the policy focus has been on the economy, change has permeated almost all aspects of life. India now engages with the world on a different plane. The coincident collapse of the Soviet Union opened up new directions for a foreign policy more consistent with a globalizing world. With the acquisition of nuclear capability in the late 1990s, its approach to defence and security has also undergone great transformation. Though much has been achieved, India is still a low–middle income emerging economy and has miles to go before poverty is truly eliminated. Only then will it be able to hold its head high and attain its rightful place in the comity of nations. 3 4 Rakesh Mohan This book chronicles the process of reform in all its different aspects through the eyes of many of the change-makers who have been among the leaders of a resurgent India. -

Padma Vibhushan * * the Padma Vibhushan Is the Second-Highest Civilian Award of the Republic of India , Proceeded by Bharat Ratna and Followed by Padma Bhushan

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Padma Vibhushan * * The Padma Vibhushan is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India , proceeded by Bharat Ratna and followed by Padma Bhushan . Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service", without distinction of race, occupation & position. Year Recipient Field State / Country Satyendra Nath Bose Literature & Education West Bengal Nandalal Bose Arts West Bengal Zakir Husain Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh 1954 Balasaheb Gangadhar Kher Public Affairs Maharashtra V. K. Krishna Menon Public Affairs Kerala Jigme Dorji Wangchuck Public Affairs Bhutan Dhondo Keshav Karve Literature & Education Maharashtra 1955 J. R. D. Tata Trade & Industry Maharashtra Fazal Ali Public Affairs Bihar 1956 Jankibai Bajaj Social Work Madhya Pradesh Chandulal Madhavlal Trivedi Public Affairs Madhya Pradesh Ghanshyam Das Birla Trade & Industry Rajashtan 1957 Sri Prakasa Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh M. C. Setalvad Public Affairs Maharashtra John Mathai Literature & Education Kerala 1959 Gaganvihari Lallubhai Mehta Social Work Maharashtra Radhabinod Pal Public Affairs West Bengal 1960 Naryana Raghvan Pillai Public Affairs Tamil Nadu H. V. R. Iyengar Civil Service Tamil Nadu 1962 Padmaja Naidu Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit Civil Service Uttar Pradesh A. Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar Medicine Tamil Nadu 1963 Hari Vinayak Pataskar Public Affairs Maharashtra Suniti Kumar Chatterji Literature