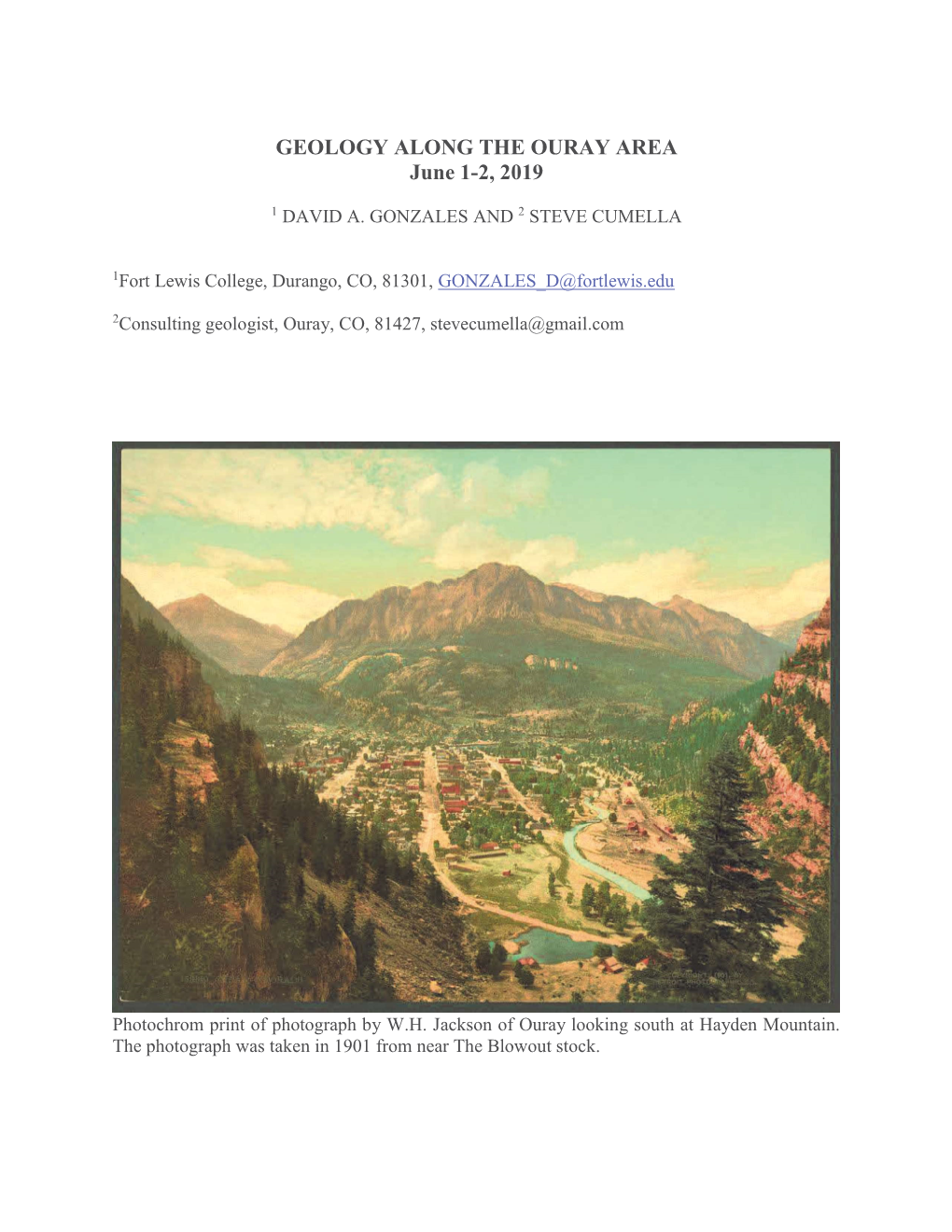

GEOLOGY ALONG the OURAY AREA June 1-2, 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Structural Interpretation of the Cherokee Arch, South

STRUCTURAL INTERPRETATION OF THE CHEROKEE ARCH, SOUTH CENTRAL WYOMING, USING 3-D SEISMIC DATA AND WELL LOGS by Joel Ysaccis B. ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to use 3-D seismic data and well logs to map the structural evolution of the Cherokee Arch, a major east-west trending basement high along the Colorado-Wyoming state line. The Cherokee Arch lies along the Cheyenne lineament, a major discontinuity or suture zone in the basement. Recurrent, oblique-slip offset is interpreted to have occurred along faults that make up the arch. Gas fields along the Cherokee Arch produce from structural and structural-stratigraphic traps, mainly in Cretaceous rocks. Some of these fields, like the South Baggs – West Side Canal fields, have gas production from multiple pays. The tectonic evolution of the Cherokee Arch has not been previously studied in detail. About 315 mi2 (815 km2) of 3-D seismic data were analyzed in this study to better understand the kinematic evolution of the area. The interpretation involved mapping the Madison, Shinarump, Above Frontier, Mancos, Almond, Lance/Fox Hills and Fort Union horizons, as well as defining fault geometries. Structure maps on these horizons show the general tendency of the structure to dip towards the west. The Cherokee Arch is an asymmetrical anticline in the hanging wall, which is mainly transected by a south-dipping series of east-west striking thrust faults. The interpreted thrust faults generally terminate within the Mancos to Above Frontier interval, and their vertical offset increases in magnitude down to the basement. Post-Mancos iii intervals are dominated by near-vertical faults with apparent normal offset. -

Ouray Hydrodam March 2017 Sediment Release Study: Uncompahgre River Near Ouray, Colorado

OURAY HYDRODAM MARCH 2017 SEDIMENT RELEASE STUDY: UNCOMPAHGRE RIVER NEAR OURAY, COLORADO PREPARED FOR THE UNCOMPAHGRE WATERSHED PARTNERSHIP PREPARED BY: ASHLEY BEMBENEK AND JULIA NAVE ALPINE ENVIRONMENTAL CONSULTANTS LLC 1 Ouray Hydrodam Release Study Uncompahgre Watershed Partnership December 2017 CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Local Drinking Water Sources .............................................................................................. 2 2.1 Ouray ................................................................................................................................ 2 2.2 Ridgway ............................................................................................................................ 2 2.3 Loghill Mesa And Dallas Creek ......................................................................................... 2 2.4 Private Wells near the Uncompahgre River ..................................................................... 2 3.0 Study Questions ................................................................................................................... 3 3.1 Sample Types and Protocols ............................................................................................ 3 Water Quality Samples ........................................................................................................... 3 Surface Sediment Samples ..................................................................................................... -

Forgotten Crocodile from the Kirtland Formation, San Juan Basin, New

posed that the narial cavities of Para- Wima1l- saurolophuswere vocal resonating chambers' Goniopholiskirtlandicus Apparently included with this material shippedto Wiman was a partial skull that lromthe Wiman describedas a new speciesof croc- forgottencrocodile odile, Goniopholis kirtlandicus. Wiman publisheda descriptionof G. kirtlandicusin Basin, 1932in the Bulletin of the GeologicalInstitute KirtlandFormation, San Juan of IJppsala. Notice of this specieshas not appearedin any Americanpublication. Klilin NewMexico (1955)presented a descriptionand illustration of the speciesin French, but essentially repeatedWiman (1932). byDonald L. Wolberg, Vertebrate Paleontologist, NewMexico Bureau of lVlinesand Mineral Resources, Socorro, NIM Localityinformation for Crocodilian bone, armor, and teeth are Goni o p holi s kir t landicus common in Late Cretaceous and Early Ter- The skeletalmaterial referred to Gonio- tiary deposits of the San Juan Basin and pholis kirtlandicus includesmost of the right elsewhere.In the Fruitland and Kirtland For- side of a skull, a squamosalfragment, and a mations of the San Juan Basin, Late Creta- portion of dorsal plate. The referral of the ceous crocodiles were important carnivores of dorsalplate probably represents an interpreta- the reconstructed stream and stream-bank tion of the proximity of the material when community (Wolberg, 1980). In the Kirtland found. Figs. I and 2, taken from Wiman Formation, a mesosuchian crocodile, Gonio- (1932),illustrate this material. pholis kirtlandicus, discovered by Charles H. Wiman(1932, p. 181)recorded the follow- Sternbergin the early 1920'sand not described ing locality data, provided by Sternberg: until 1932 by Carl Wiman, has been all but of Crocodile.Kirtland shalesa 100feet ignored since its description and referral. "Skull below the Ojo Alamo Sandstonein the blue Specimensreferred to other crocodilian genera cley. -

Uncompahgre Project

Uncompahgre Project David Clark Wm. Joe Simonds, ed. Bureau of Reclamation 1994 Table of Contents Uncompahgre Project...........................................................2 Project Location.........................................................2 Historic Setting .........................................................2 Project Authorization.....................................................5 Construction History .....................................................5 Post-Construction History................................................10 Settlement of the Project .................................................13 Uses of Project Water ...................................................14 Conclusion............................................................15 Bibliography ................................................................16 Government Documents .................................................16 Books ................................................................16 Articles...............................................................16 Index ......................................................................18 1 Uncompahgre Project Uncompahgre is a Ute word meaning as follows; Unca-=hot; pah=water, gre=spring. One of the oldest Reclamation projects, the Uncompahgre Project contains one storage dam, several diversion dams, 128 miles of canals, 438 miles of laterals and 216 miles of drains. The project includes mesa and valley land on the western slope of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado at an elevation -

Pleistocene Drainage Changes in Uncompahgre Plateau-Grand

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/32 Pleistocene drainage changes in Uncompahgre Plateau-Grand Valley region of western Colorado, including formation and abandonment of Unaweep Canyon: a hypothesis Scott Sinnock, 1981, pp. 127-136 in: Western Slope (Western Colorado), Epis, R. C.; Callender, J. F.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 32nd Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 337 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1981 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

Journal of the Western Slope

JOURNAL OF THE WESTERN SLOPE VO LUME II. NUMBER 1 WINTER 1996 ~,. ~. I "Queen" Chipeta-page I Audre Lucile Ball : Her Life in the Grand Valley From World War 1I Through Ihe Fifties-page 23 JOURNAL OF THE WESTERN SLOPE is published quarterly by two student organizations at Mesa State College: the Mesa State College Historical Society and the Alpha-Gamma-Epsilon Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta. Annual subscriptions are $14. (Single copies are available by contacting the editors of the Journal.) Retailers are en couraged to write for prices. Address subscriptions and orders for back issues to: Mesa State College Journal of the Western Slope P.O. Box 2647 Grand Junction, CO 81502 GUIDELINES FOR CONTRIBUTORS: The pu'pOSfI 01 THE X>URNAl OF THE WESTERN SlOf'E is 10 I!flCOUrIIge tdloIarly sl\l(!y 01 CoIorIIdD'$ Western Slope. The primary goat is to pre5erve !loci leeonl its hislory; IIowewI. IttideS on anlhlopology', economics, govemmelli. naltJfal histOtY. arod SOCiology will be considered. Author$hlP is open 10 anyomt who wishel to svbmiI original and 5dloIarly malerialliboullhe WMteln Slope. The ed~OtS encourage teners oIlnq~ .rom prOSp8CIlYG authors. 5eI'Id matMiahs lind IellafS 10 THE JOURNAL Of THE WESTERN SLOPE, MeS<! State College. P.O. Box 26<&7. Grand June tion,C081502, I ) ConlrlbulOfS are requasled 10 senCIltleir mallUscript on an IBM-compalibla disk. DO NOT SEND THE ORIGINAL. Editol1l will not retlJm disl\s, Matarial snoold be tootnoted. The editors will give preien,.... ce to submissions at about IMrnly·live pages. 2) AlkJw thtlll(!itol1l sixty days to review mar.uscripts. -

The Frontiers of American Grand Strategy: Settlers, Elites, and the Standing Army in America’S Indian Wars

THE FRONTIERS OF AMERICAN GRAND STRATEGY: SETTLERS, ELITES, AND THE STANDING ARMY IN AMERICA’S INDIAN WARS A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Andrew Alden Szarejko, M.A. Washington, D.C. August 11, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Andrew Alden Szarejko All Rights Reserved ii THE FRONTIERS OF AMERICAN GRAND STRATEGY: SETTLERS, ELITES, AND THE STANDING ARMY IN AMERICA’S INDIAN WARS Andrew Alden Szarejko, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Andrew O. Bennett, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Much work on U.S. grand strategy focuses on the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. If the United States did have a grand strategy before that, IR scholars often pay little attention to it, and when they do, they rarely agree on how best to characterize it. I show that federal political elites generally wanted to expand the territorial reach of the United States and its relative power, but they sought to expand while avoiding war with European powers and Native nations alike. I focus on U.S. wars with Native nations to show how domestic conditions created a disjuncture between the principles and practice of this grand strategy. Indeed, in many of America’s so- called Indian Wars, U.S. settlers were the ones to initiate conflict, and they eventually brought federal officials into wars that the elites would have preferred to avoid. I develop an explanation for settler success and failure in doing so. I focus on the ways that settlers’ two faits accomplis— the act of settling on disputed territory without authorization and the act of initiating violent conflict with Native nations—affected federal decision-making by putting pressure on speculators and local elites to lobby federal officials for military intervention, by causing federal officials to fear that settlers would create their own states or ally with foreign powers, and by eroding the credibility of U.S. -

Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests REVISED DRAFT Forest Assessments: Watersheds, Water, and Soil Resources March 2018

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests REVISED DRAFT Forest Assessments: Watersheds, Water, and Soil Resources March 2018 Taylor River above Taylor Dam, Gunnison Ranger District In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. -

The Colorado Magazine

THE COLORADO MAGAZINE Published by The State Historical and Natural History Society of Colorado Devoted to the Interests of the Society, Colorado, and the West Copyrighted 1924 by the State Historical and Natural History Society of Colorado. VOL. Denver, Colorado, November, 1924 NO. 7 Spanish Expeditions Into Colorado:f. By Alfred Barnaby Thomas, M. A., Berkeley, California. I. INTRODUCTION We customarily associate Spanish explorations in the West with New Mexico, with Texas, with Arizona, or with California, but not with Colorado. Yet Spaniards in the eighteenth century were well acquainted with large portions of the region now com prised in that state. Local historians of Colorado often err by pushing the clock too far back, and asserting that Coronado, Oriate, and other sixteenth century conquistadores entered the state. On the other hand, they fail to mention several important expeditions which at a later date did enter the confines of the state. An Outpost of New Mexico.-The Colorado region in Span ish days was a frontier of New Mexico. Santa Fe was the base for Colorado as San Agustin was for Georgia. Three interests especially spurred the New Mexicans to make long journeys northward to the Platte River, to the upper Arkansas in central Colorado, and to the Dolores, Uncomphagre, Gunnison, and Grand Rivers on the western borders. These interests were Indians, French intruders, and rumored mines. After 1673 reports of Frenchmen in the Pawnee country constantly worried officials at Santa Fe. Frequently tales of gold and sil'ver were wafted southward to sensitive Spanish ears at the New Mexico capital. -

Geologic History of the San Juan Basin Area, New Mexico and Colorado Edward C

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/1 Geologic history of the San Juan Basin area, New Mexico and Colorado Edward C. Beaumont and Charles B. Read, 1950, pp. 49-54 in: San Juan Basin (New Mexico and Colorado), Kelley, V. C.; Beaumont, E. C.; Silver, C.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 1st Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 152 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1950 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society has held an annual Fall Field Conference that visits some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an important reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads The New Mexico Geological Society has decided to make our peer-reviewed Fall Field Conference guidebook papers available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers, but not from the last two years. Members will have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of the societies' operating budget. Therefore, only research papers will be made available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content will remain available only in the printed guidebooks. -

THREE SACRED VALLEYS): an Assessment of Native American Cultural Resources Potentially Affected by Proposed U.S

Paitu Nanasuagaindu Pahonupi (THREE SACRED VALLEYS): An Assessment of Native American Cultural Resources Potentially Affected by Proposed U.S. Air Force Electronic Combat Test Capability Actions and Alternatives at the Utah Test and Training Range Item Type Report Authors Stoffle, Richard W.; Halmo, David; Olmsted, John Publisher Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan Download date 01/10/2021 12:00:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/271235 PAITU NANASUAGAINDU PAHONUPI(THREE SACRED VALLEYS): AN ASSESSMENT OF NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURAL RESOURCES POTENTIALLY AFFECTED BY PROPOSED U.S. AIR FORCE ELECTRONIC COMBAT TEST CAPABILITY ACTIONS AND ALTERNATIVES AT THE UTAH TEST AND TRAINING RANGE DRAFT INTERIM REPORT By Richard W. Stoffle David B. Halmo John E. Olmsted Institute for Social Research University of Michigan April 14, 1989 Submitted to: Science Applications International Corporation Las Vegas, Nevada TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Description of Study Area 2 Description of Project 2 Site Specific Assessment 3 Tactical Threat Area 3 Threat Sites and Array 4 Range Maintenance Facilities 4 Programmatic Assessment 5 Airspace and Flight Activities Effects 5 Gapfiller Radar Site 5 Future Programmatic Assessments 5 Commercial Power 5 Fiber -optic Communications Network 5 Project - Related Structures and Activities on DOD lands 5 CHAPTER TWO ETHNOHISTORY OF INVOLVED NATIVE AMERICAN GROUPS 7 Ethnic Groups and Territories 7 Overview 7 Gosiutes 9 Pahvants 12 Utes 13 Early Contact, Euroamerican Colonization, -

Central San Juan Basin

Acta - ---- - - ---Palaeontologic- -- ---' ~ Polonica Vol. 28, No. 1-2 pp. 195-204 Warszawa, 1983 Second Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestiol. Ecosystems, Jadwisin 1981 SPENCER G. LUCAS and NIALL J. MATEER VERTEBRATE PALEOECOLOGY OF THE LATE CAMPANIAN (CRETACEOUS):FRUITLAND FORMATION, SAN JUAN BASIN, ~EW MEXICO (USA) LUCAS, s. G. and MATEER, N. J .: Vertebrate paleoecology of the late Campanian (Cretaceous) Fruitland Formation, San Juan Basin, New Mexico (USA). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 28, 1-2, 195-204, 1983. Sediments of the Fruitland Formation in northwestern New Mexico represent a delta plain that prograded northeastward over the retrating strandline of the. North American epeiric seaway during the late Campanian. Fruitland fossil · vertebrates are fishes, amphibians, lizards, a snake, turtles, crocodilians, dinosaurs (mostly h adrosaurs and ceratopsians) and mammals. Autochthonous fossils in the Fruitland ' Form ation represent organisms of the trophically-complex Para saurolophus community. Differences in diversity, physical stress and life-history strategies within the ParasaurolopllUS community . fit well the stablllty-time hypothesis. Thus, dinosaurs experienced relatively low physical stress whereas fishes, amphibians, small reptiles and mammals experienced greater physical stress. Because of this, dinosaurs were less likely to recover from an environment al catastrophe than were smaller contemporaneous vertebrates. The terminal Cretaceous extinctions selectively eliminated animals that lived in less physlcally -stressed situations, indicating that the extinctions resulted from an environmental catastrophe. Key w 0 r d s: Fruitland Formation, New Mexico, delta plain, stablllty-time hypothesis, Cretaceous extinctions. Spencer G. Lucas, Department ot Geology and Geophysics and Peabody Museum ot Natural History, Yale University, P.O. Box 6666, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ; NlaU J .