The Story of the Irish Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare

Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare 2000 ‘Former Republicans have been bought off with palliatives’ Cathleen Knowles McGuirk, Vice President Republican Sinn Féin delivered the oration at the grave of Theobald Wolfe Tone, the founder of Irish Republicanism, on Sunday, June 11 in Bodenstown cemetery, outside Sallins, Co Kildare. The large crowd, led by a colour party carrying the National Flag and contingents of Cumann na mBan and Na Fianna Éireann, as well as the General Tom Maguire Flute Band from Belfast marched the three miles from Sallins Village to the grave of Wolfe Tone at Bodenstown. Contingents from all over Ireland as well as visitors from Britain and the United States took part in the march, which was marshalled by Seán Ó Sé, Dublin. At the graveside of Wolfe Tone the proceedings were chaired by Seán Mac Oscair, Fermanagh, Ard Chomhairle, Republican Sinn Féin who said he was delighted to see the large number of young people from all over Ireland in attendance this year. The ceremony was also addressed by Peig Galligan on behalf of the National Graves Association, who care for Ireland’s patriot graves. Róisín Hayden read a message from Republican Sinn Féin Patron, George Harrison, New York. Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare “A chairde, a comrádaithe agus a Phoblactánaigh, tá an-bhród orm agus tá sé d’onóir orm a bheith anseo inniu ag uaigh Thiobóid Wolfe Tone, Athair an Phoblachtachais in Éirinn. Fellow Republicans, once more we gather here in Bodenstown churchyard at the grave of Theobald Wolfe Tone, the greatest of the Republican leaders of the 18th century, the most visionary Irishman of his day, and regarded as the “Father of Irish Republicanism”. -

HISTORY MEDIUM TERM PLAN (MTP) YEAR 4 2020: Taught 1St Half of Each Term HISTORY MTP Y4 Autumn 1: 8 WEEKS Spring 1: 6 WEEKS Su

HISTORY MEDIUM TERM PLAN (MTP) YEAR 4 2020: Taught 1st half of each term HISTORY Autumn 1: 8 WEEKS Spring 1: 6 WEEKS Summer 1: 6 WEEKS MTP Y4 Topic Title: Anglo-Saxons / Scots Topic Title: Vikings Topic Title: UK Parliament Taken from the Year Key knowledge: Key knowledge: Key knowledge: group • Roman withdrawal from Britain in CE • Viking raids and the resistance of Alfred the Great and • Establishment of the parliament - division of the curriculum 410 and the fall of the western Roman Athelstan. Houses of Lords and Commons. map Empire. • Edward the Confessor and his death in 1066 - prelude to • Scots invasions from Ireland to north the Battle of Hastings. Key Skills: Britain (now Scotland). • Anglo-Saxons invasions, settlements and Key Skills: kingdoms; place names and village life • Choose reliable sources of information to find out culture and Christianity (eg. Canterbury, about the past. Iona, and Lindisfarne) • Choose reliable sources of information to find out about • Give own reasons why changes may have occurred, the past. backed up by evidence. • Give own reasons why changes may have occurred, • Describe similarities and differences between people, Key Skills: backed up by evidence. events and artefacts. • Describe similarities and differences between people, • Describe how historical events affect/influence life • Choose reliable sources of information events and artefacts. today. to find out about the past. • Describe how historical events affect/influence life today. Chronological understanding • Give own reasons why changes may Chronological understanding • Understand that a timeline can be divided into BCE have occurred, backed up by evidence. • Understand that a timeline can be divided into BCE and and CE. -

Now and Again

Now and Again Current and Recurring Issues facing Irish Archaeologists IAI Conference 2019 Institute of Archaeologists of Ireland 1 Friday 5th April 8.20–9.00 Registration 9.00–9.10 Introduction by Dr James Bonsall, Chairperson of the IAI. Session 1 Part 1: Key Stakeholder Presentations 9.15–9.25 Maeve Sikora, National Museum of Ireland, Keeper of Irish Antiquities. Current issues for the National Museum of Ireland. 9.25–9.45 Johanna Vuolteenaho, Historic Environment Division, Heritage Advice and Regulations. Way Forward for Archaeology in Northern Ireland—Training and skills. 9.45–9.55 Ciara Brett, Local Authority Archaeologists Network. Archaeology and the Local Authority—Introduction to the Local Authority Archaeologists Network (LAAN). 10.00–10.20 Ian Doyle, Heritage Council of Ireland, Head of Conservation. Public attitudes to archaeology: recent research by the Heritage Council and RedC. Institute of Archaeologists of Ireland, 63 Merrion Square, Dublin 2 @IAIarchaeology #IAI2019 2 10.20–10.30 Christine Baker, Fingal County Council, Community Archaeologist. Community Archaeology. 10.30–10.40 Dr Charles Mount, Irish Concrete Federation, Project Archaeologist. Archaeological heritage protection in the Irish Concrete Federation. 10.40–11.00 Tea and Coffee Session 1 Part 2: Key Stakeholder Presentations 11.00–11.15 Michael MacDonagh, National Monuments Service, Chief Archaeologist. What role the State in terms of professionalisation? 11.15–11.35 Dr Clíodhna Ní Lionáin, UNITE Archaeological Branch. Fiche Bliain ag Fás—Lessons Learned from 20 Years in Archaeology. 11.35–11.45 Nick Shepard, Federation of Archaeological Managers and Employers, Chief Executive. FAME— the voice of commercial archaeology in Ireland? Institute of Archaeologists of Ireland, 63 Merrion Square, Dublin 2 @IAIarchaeology #IAI2019 3 11.45–12.05 Dr Edel Bhreathnach, The Discovery Programme, former CEO. -

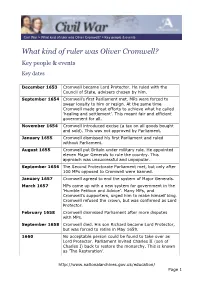

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Coen Trophy (Mixed Teams Championship)

CBAI National Presidents Duais An Uachtarain (President’s Prize) Spiro Cup (Mixed Pairs Championship) Coen Trophy (Mixed Teams Championship) Master Pairs (National Open Pairs) Holmes Wilson Cup (National Open Teams) Revington Cup (Men’s Pairs) Jackson Cup (Women’s Pairs) Geraldine Trophy (Men’s Teams) McMenamin Bowl (Women’s Teams) Lambert Cup (National Confined Pairs) Cooper Cup (National Confined Teams) Davidson Cup (National Open Pairs) Laird Cup (National Intermediate A Pairs) Civil Service Cup (National Intermediate B Pairs) Kelburne Cup (National Open Teams) Bankers Trophy (National Intermediate A Teams) Tierney Trophy (National Intermediate B Teams) Home International Series Burke Trophy (IBU Inter-County Teams) O’Connor Trophy (IBU Inter-County Intermediate Teams) Frank & Brenda Kelly Trophy (Inter-County 4Fun Teams) Novice & Intermediate Congress JJ Murphy Trophy (National Novice Pairs) IBU Club Pairs Egan Trophy (IBU All-Ireland Teams) Moylan Cup (IBU All-Ireland Pairs) IBU Seniors’ Congress CBAI National Presidents 2019 Neil Burke 2016 Pat Duff 2017 Jim O’Sullivan 2018 Peter O’Meara 2013 Thomas MacCormac 2014 Fearghal O’Boyle 2015 Mrs Freda Fitzgerald 2010 Mrs Katherine Lennon 2011 Mrs Sheila Gallagher 2012 Liam Hanratty 2007 Mrs Phil Murphy 2008 Martin Hayes 2009 Mrs Mary Kelly-Rogers 2004 Mrs Aileen Timoney 2005 Paddy Carr 2006 Mrs Doreen McInerney 2001 Seamus Dowling 2002 Mrs Teresa McGrath 2003 Mrs Rita McNamara 1998 Peter Flynn 1999 Mrs Kay Molloy 2000 Michael O’Connor 1995 Denis Dillion 1996 Mrs Maisie Cooper 1997 Mrs -

FLAG of IRELAND - a BRIEF HISTORY Where in the World

Part of the “History of National Flags” Series from Flagmakers FLAG OF IRELAND - A BRIEF HISTORY Where In The World Trivia The Easter Rising Rebels originally adopted the modern green-white-orange tricolour flag. Technical Specification Adopted: Officially 1937 (unofficial 1916 to 1922) Proportion: 1:2 Design: A green, white and orange vertical tricolour. Colours: PMS – Green: 347, Orange: 151 CMYK – Green: 100% Cyan, 0% Magenta, 100% Yellow, 45% Black; Orange: 0% Cyan, 100% Magenta 100% Yellow, 0% Black Brief History The first historical Flag was a banner of the Lordship of Ireland under the rule of the King of England between 1177 and 1542. When the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 made Henry VII the king of Ireland the flag became the Standard of the Kingdom of Ireland, a blue field featuring a gold harp with silver strings. The Banner of the Lordship of Ireland The Royal Standard of the Kingdom of Ireland (1177 – 1541) (1542 – 1801) When Ireland joined with Great Britain to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801, the flag was replaced with the Flag of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. This was flag of the United Kingdom defaced with the Coat of Arms of Ireland. During this time the Saint Patrick’s flag was also added to the British flag and was unofficially used to represent Northern Ireland. The Flag of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland The Cross of Saint Patrick (1801 – 1922) The modern day green-white-orange tricolour flag was originally used by the Easter Rising rebels in 1916. -

National Museum of Ireland 2010 Annual Report

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF IRELAND 2010 ANNUAL REPORT 1 Contents Message from the Chairman of the Board of the National Museum of Ireland Introduction by the Director of the National Museum of Ireland Collections Art and Industry Irish Antiquities Irish Folklife Natural History Conservation Registration Services Education and Outreach Marketing Photographic Design Facilities (Accommodation and Security) Administration General Financial Management Human Resource Management Information Communications Technology (ICT) Financial Statements 1st January 2010- 31st December 2010 Publications by NMI Staff Board of the National Museum of Ireland Staff Directory 2 Message from the Chairman of the Board of the National Museum of Ireland This was the final year of tenure of the Board of the National NMI of Ireland which was appointed in May 2005 and which terminated in May 2010. The Board met three times in 2010 prior to the termination of its term of office in May 2005. It met on 4th February 2010, 4th March 2010, and 21st April 2010. The Audit Committee of the Board met on three occasions in 2010 - being 14th January, 31st March, and 21st April. The Committee reviewed and approved the Financial Statements, and the Board duly approved, and signed off on, the same on 21st April 2010. The Audit Committee conducted interviews for the appointment for a new three-year period for the internal audit function. Deloitte was the successful applicant, and the Board approved of the awarding of the contract at its meeting of 21st April 2010. The internal auditors produced a draft audit plan for the period 1st July 2010 to 30th June 2013, and presented it to the NMI for consideration in July. -

Symbols of Power in Ireland and Scotland, 8Th-10Th Century Dr

Symbols of power in Ireland and Scotland, 8th-10th century Dr. Katherine Forsyth (Department of Celtic, University of Glasgow, Scotland) Prof. Stephen T. Driscoll (Department of Archaeology, University of Glasgow, Scotland) d Territorio, Sociedad y Poder, Anejo Nº 2, 2009 [pp. 31-66] TSP Anexto 4.indb 31 15/11/09 17:22:04 Resumen: Este artículo investiga algunos de los símbolos utilizaron las cruces de piedra en su inserción espacial como del poder utilizados por las autoridades reales en Escocia signos de poder. La segunda parte del trabajo analiza más e Irlanda a lo largo de los siglos viii al x. La primera parte ampliamente los aspectos visibles del poder y la naturaleza del trabajo se centra en las cruces de piedra, tanto las cruces de las sedes reales en Escocia e Irlanda. Los ejemplos exentas (las high crosses) del mundo gaélico de Irlanda estudiados son la sede de la alta realeza irlandesa en Tara y y la Escocia occidental, como las lastras rectangulares la residencia regia gaélica de Dunnadd en Argyll. El trabajo con cruz de la tierra de los pictos. El monasterio de concluye volviendo al punto de partida con el examen del Clonmacnoise ofrece un ejemplo muy bien documentado centro regio picto de Forteviot. de patronazgo regio, al contrario que el ejemplo escocés de Portmahomack, carente de base documental histórica, Palabras clave: pictos, gaélicos, escultura, Clonmacnoise, pero en ambos casos es posible examinar cómo los reyes Portmahomack, Tara, Dunnadd, Forteviot. Abstract: This paper explores some of the symbols of power landscape context as an expression of power. -

Francis Dobbs and the Acton Volunteers Layout 1 23/10/2013 10:12 Page 1

Francis Dobbs and the Acton Volunteers _Layout 1 23/10/2013 10:12 Page 1 POYNTZPASS AND DISTRICT LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY 15 FRANCIS DOBBS AND THE ACTON VOLUNTEERS BY BARBARA BEST “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair….” (‘A Tale of Two Cities’: Charles Dickens) he famous opening lines of Dickens’ classic novel, about events in Paris and London in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, could equallyT apply to Ireland during that time, for it was a period of many great dramatic events the effects of which, in some cases, remain to the present day. In all great dramas there are leading characters and while names such as those of Grattan, Flood, Tone and McCracken are well-remembered, one of those supporting characters who deserves to be better known, is Francis Dobbs. Who was Francis Dobbs, and what is his local connection? In his, ‘Historic Memoirs of Ireland’ (Vol. 2) Sir Jonah Barrington described Francis Dobbs as “a gentleman of respectable family but moderate fortune.” He was the younger son of the Reverend Richard Dobbs of Castle Dobbs, Francis Dobbs (1750-1811) Co. Antrim, and grandson of Richard Dobbs of Castle Dobbs(1660-1711) who, as Mayor, greeted William of writing plays and poetry. His play ‘The Irish Chief or Patriot Orange when he landed at Carrickfergus in 1688. -

Concealed Criticism: the Uses of History in Anglonorman Literature

Concealed Criticism: The Uses of History in AngloNorman Literature, 11301210 By William Ristow Submitted to The Faculty of Haverford College In partial fulfillment of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in History 22 April, 2016 Readers: Professor Linda Gerstein Professor Darin Hayton Professor Andrew Friedman Abstract The twelfth century in western Europe was marked by tensions and negotiations between Church, aristocracy, and monarchies, each of which vied with the others for power and influence. At the same time, a developing literary culture discovered new ways to provide social commentary, including commentary on the power-negotiations among the ruling elite. This thesis examines the the functions of history in four works by authors writing in England and Normandy during the twelfth century to argue that historians used their work as commentary on the policies of Kings Stephen, Henry II, and John between 1130 and 1210. The four works, Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, Master Wace’s Roman de Brut, John of Salisbury’s Policraticus, and Gerald of Wales’ Expugnatio Hibernica, each use descriptions of the past to criticize the monarchy by implying that the reigning king is not as good as rulers from history. Three of these works, the Historia, the Roman, and the Expugnatio, take the form of narrative histories of a variety of subjects both imaginary and within the author’s living memory, while the fourth, the Policraticus, is a guidebook for princes that uses historical examples to prove the truth of its points. By examining the way that the authors, despite the differences between their works, all use the past to condemn royal policies by implication, this thesis will argue that Anglo-Norman writers in the twelfth century found history-writing a means to criticize reigning kings without facing royal retribution. -

But the Irish Sea Betwixt Us: Ireland, Colonialism, and Renaissance Literature

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, British Isles English Language and Literature 1999 But the Irish Sea Betwixt Us: Ireland, Colonialism, and Renaissance Literature Andrew Murphy University of St. Andrews Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Murphy, Andrew, "But the Irish Sea Betwixt Us: Ireland, Colonialism, and Renaissance Literature" (1999). Literature in English, British Isles. 16. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_british_isles/16 Irish Literature, History, & Culture Jonathan Allison, General Editor Advisory Board George Bornstein, University of Michigan Elizabeth Butler Cullingford, University of Texas James S. Donnelly Jr., University of Wisconsin Marianne Elliott, University of Liverpool Roy Foster, Hertford College, Oxford David Lloyd, University of California, Berkeley Weldon Thornton, University of North Carolina This page intentionally left blank But the Irish Sea Betwixt Us Ireland, Colonialisn1, and Renaissance Literature Andrew Murphy THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1999 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2009 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. -

The Great Gas Giveaway

Giving Away The Gas 26/05/2009 17:31 Page 1 The Great Gas Giveaway How the elites have gambled with our health and wealth An Afri Report Giving Away The Gas 26/05/2009 17:31 Page 2 Andy Storey and Michael McCaughan Giving Away The Gas 26/05/2009 17:31 Page 3 Giving away the gas “We gave the Corrib gas away and now Éamon Ryan is intent on giving away the remaining choice areas of our offshore acreage at less than bargain basement prices”. 1 An international study in 2002 found that only Cameroon took a lower share of the revenues from its own oil or gas resources than Ireland – the vast majority of countries demand that multinational oil and gas companies pay the state proportionately twice the amount that the Irish government is extracting from the Shell-led consortium that is exploiting the Corrib gas field. Ghana, for example, insists that the state-owned Ghanaian National Petroleum Corporation has a 10 per cent ownership stake in any resource find and the multinationals are also liable to a 50 per cent profits tax. Ireland, by contrast, demands no state shareholding in any resource finds, nor does it demand royalty payments. A generous (to the companies) tax rate of only 25 per cent applies – and even that low tax rate only kicks in after a company’s exploration and development costs (and the estimated costs of closing down the operation when the resources are depleted) have been recovered.2 The Corrib gas field will probably be half depleted before any tax is paid at all.