Lessons from the Motor City: Why Detroit Matters for the 21St Century World by Brian Doucet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

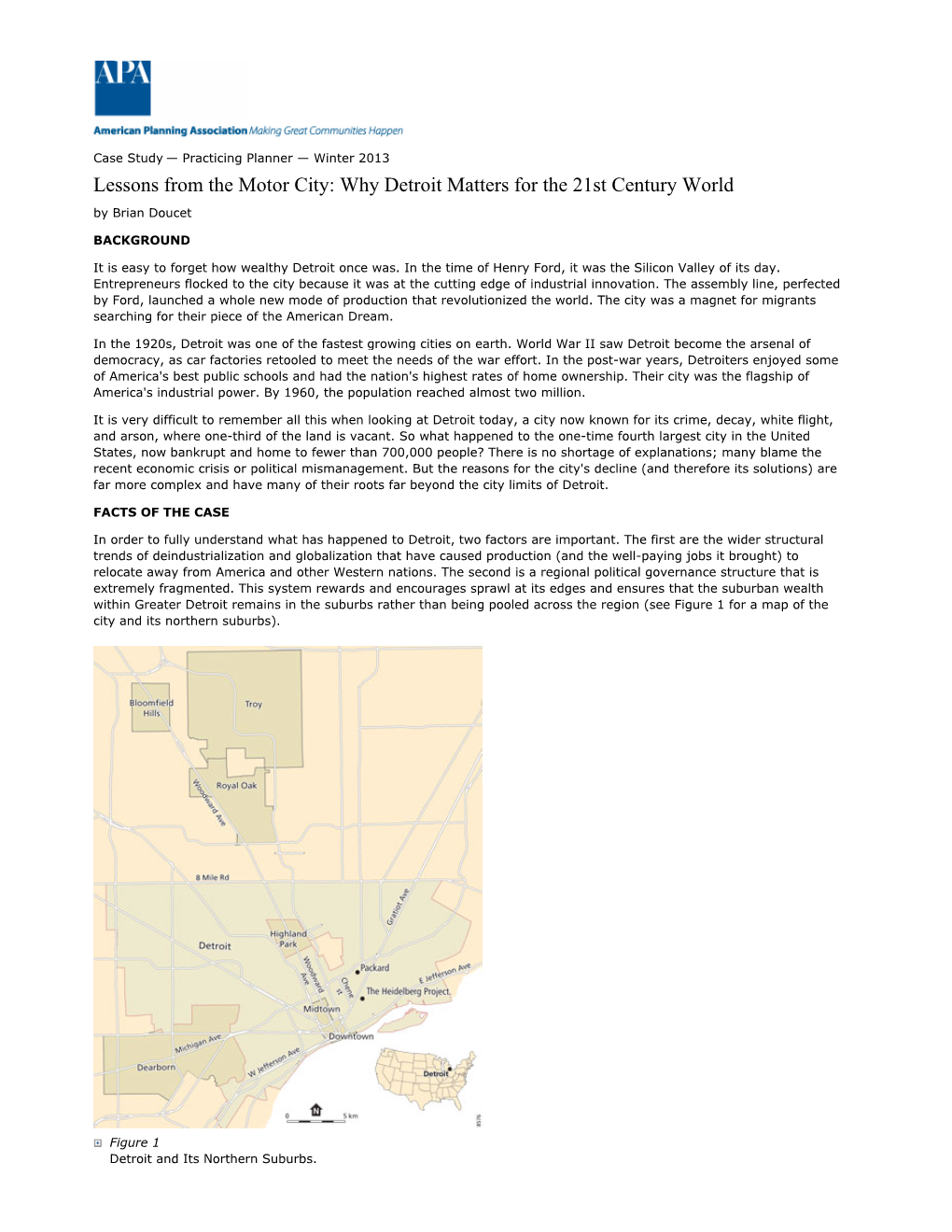

Detroit Neighborhoods

St Clair Shores Oak Park Ferndale Hazel Park Warren Southfield Eastpointe 43 68 85 8 29 42 93 Harper Woods 83 34 7 90 78 16 44 19 54 97 4 95 105 76 77 56 94 86 60 72 33 26 6 45 81 67 84 69 88 58 Hamtramck 17 74 Redford Twp 12 103 39 30 40 1 89 41 71 15 9 20 100 66 80 96 70 82 5 51 36 57 2 38 49 27 59 99 23 35 32 73 62 61 50 46 3 37 53 104 52 28 102 13 31 79 98 21 64 55 11 87 18 22 25 65 63 101 47. Hubbard Farms 48 48. Hubbard Richard 77. Palmer Park 47 91 19. Conant Gardens 49. Indian Village 78. Palmer Woods Dearborn 20. Conner Creek 50. Islandview 79. Parkland 92 21. Core City 51. Jefferson Chalmers 80. Petosky-Otsego 22. Corktown 52. Jeffries 81. Pilgrim Village 23. Cultural Center 53. Joseph Berry Subdivision 82. Poletown East 24 Inkster 24. Delray 54. Krainz Woods 83. Pulaski 25. Downtown 55. Lafayette Park 84. Ravendale 75 14 26. East English Village 56. LaSalle College Park 85. Regent Park Melvindale 27. East Village 57. LaSalle Gardens 86. Riverdale 28. Eastern Market 58. Littlefield 87. Rivertown Dearborn Heights River Rouge 1. Arden Park 29. Eight Mile-Wyoming 59. Marina District 88. Rosedale Park 10 2. Art Center 30. Eliza Howell 60. Martin Park 89. Russell Woods 3. Aviation Sub 31. Elmwood Park 61. McDougall-Hunt 90. Sherwood Forest 4. Bagley 32. Fiskhorn 62. -

Growing Detroit's African-American Middle

v GROWING DETROIT’S AFRICAN-AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS THE OPPORTUNITY FOR A PROSPEROUS DETROIT GROWING DETROIT’S AFRICAN-AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS THE OPPORTUNITY FOR A PROSPEROUS DETROIT Photography Tafari Stevenson-Howard 1st Printing: February 2019 GROWING DETROIT’S AFRICAN-AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS THE OPPORTUNITY FOR A PROSPEROUS DETROIT 4 FOREWORD Foreword There’s a simple, universal concept concerning economic, social and educational growth that must be front of mind in planning about enlarging the black middle class: Authentic development and growth require deliberate investment. If we want to see more black people enter the middle class, we must invest in endeavors and interventions that lead to better- paying jobs, affordable housing, efficient transportation and effective schools. Though these amenities will attract middle- class people back to Detroit, the focus on development must be directed at uplifting a greater percentage of current residents so that they have the necessary tools to enter the middle class. Meaning, growing the black middle class in Detroit should not result from pushing low-income people out of the city. One may think a strategy to attract people back into to the city should take priority. White and middle-class flight significantly influenced the concentrations of families who make less than $50,000 in the suburbs (30 percent) and in Detroit (75 percent), according to findings in Detroit Future City’s “139 Square Miles” report. Bringing suburbanites back into the city would alter these percentages, and we most certainly want conditions that are attractive to all middle- class families. However, we also don’t want to return to the realities where the devaluing of low-income and black people hastened the flight to the suburbs. -

Challenge Detroit Is Back, Partnering with Culture Source, for Our Second to Last Challenge

Challenge Detroit is back, partnering with Culture Source, for our second to last challenge. Culture Source advocates and supports many of the great arts and culture nonprofits located Southeast Michigan. There are roughly 120 nonprofit members of Culture Source, ranging from the Henry Ford to MOCAD to Pewabic Pottery. Our challenge will enhance their new marketing and fundraising campaign, which launches in 2014. The Fellows will - BLAST provide data and ideas to help market the campaign towards young creative adults who live in Detroit and Southeast Michigan. We will uncover what young creative adults see as challenges when attending cultural engagements and if these barriers prevent them from attending other events. Similarly, the Fellows will find young creative adult’s motivation for getting involved in cultural activities and what can currently be tweaked to make cultural events more enjoyable. Spotlight: Sarah Grieb If you are interested in learning more about Culture Source, please checkout their website. You may want to take advantage of the Charitable Volunteer Program and participate in an event with others at Billhighway. Also, check out the Challenge Detroit Fellows via their weekly spotlights. You can find more videos and older spotlights here at the Challenge Detroit Youtube page. -Isaac Light Up the Riverfront Livernois Corridor Soup Women 2.0 Founder Friday Orion Festival Motor City Pride Walk Fashion Show Thursday, June 6th 6-10pm Thursday, June 6th 6-9pm Friday, June 7th 6-9pm June 8th-9th June 8th-9th Saturday, June 8th 7:30-11pm Indian Village Detroit Youth Soup Detroit FC Slow Roll Home & Garden Tour Sunday, June 9th 4-7pm Sunday, June 9th 1-4pm Monday, June 10th 7-10pm Saturday, June 8th 10am-5pm Edition: 6/5/13 - 6/12/13. -

The Detroit Housing Market Challenges and Innovations for a Path Forward

POLICYADVISORY GROUP RESEARCH REPORT The Detroit Housing Market Challenges and Innovations for a Path Forward Erika C. Poethig Joseph Schilling Laurie Goodman Bing Bai James Gastner Rolf Pendall Sameera Fazili March 2017 ABOUT THE URBAN INSTITUTE The nonprofit Urban Institute is dedicated to elevating the debate on social and economic policy. For nearly five decades, Urban scholars have conducted research and offered evidence-based solutions that improve lives and strengthen communities across a rapidly urbanizing world. Their objective research helps expand opportunities for all, reduce hardship among the most vulnerable, and strengthen the effectiveness of the public sector. Copyright © March 2017. Urban Institute. Permission is granted for reproduction of this file, with attribution to the Urban Institute. Cover image by Tim Meko. Contents Acknowledgments iv Sustaining a Healthy Housing Market 1 Demand 1 Supply 10 Credit Access 23 What’s Next? 31 Innovations for a Path Forward 32 Foreclosed Inventory Repositioning 34 Home Equity Protection 38 Land Bank Programs 40 Lease-Purchase Agreements 47 Shared Equity Homeownership 51 Targeted Mortgage Loan Products 55 Rental Housing Preservation 59 Targeting Resources 60 Capacity 62 Translating Ideas into Action 64 Core Principles for Supporting Housing Policies and Programs in Detroit 64 A Call for a Collaborative Forum on Housing: The Detroit Housing Compact 66 Notes 70 References 74 The Urban Institute's Collaboration with JPMorgan Chase 76 Statement of Independence 77 Acknowledgments This report was funded by a grant from JPMorgan Chase. We are grateful to them and to all our funders, who make it possible for Urban to advance its mission. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. -

2004 Annual Report in PDF Format

“Coming together is a beginning. Keeping together is progress. Working together is success.” Henry Ford A Welcome from the Chairman and the President Where do great ideas come from? Who will plant the seeds of inspiration for gen- erations to come? How can we ensure a better tomorrow? Who will be the next Edison or Einstein, the next John F. Kennedy or Rosa Parks? Who will be the next ordinary person with an idea that changes the world? The Inspiration Project: The Campaign to Transform The Henry Ford rises to answer these important questions. On October 21, 2004, this bold initiative was presented to 250 community lead- ers who gathered to commemorate The Henry Ford’s landmark 75th anniversary and the many extraordinary moments in its history that have inspired generations.They also learned about the host of endeavors that are carrying us toward an even brighter future with new and revitalized exhibits and galleries, improved services and facilities, and robust new programming. The Inspiration Project is helping us secure the funds necessary to develop these expe- riences.The scope of investors in this effort is truly inspiring. By the end of 2004, we accomplished 75 percent of our strategic plan goals and raised more than 75 percent of the campaign’s $155 million goal—a fitting accomplishment for our 75th anniversary. We thank our investors and join them in inviting everyone who believes in the value of this institution to make a contribution to the Inspiration Project. Dollars invested wisely today will be an inspiration to the ordinary visitors who may someday transform all of our daily lives into extraordinary ones. -

African American Brochure

2004 Legacyof the NorthernStar Metro Detroit’s guide to African-American cultural attractions and points of interest Legacyof the NorthernStar Reasons to visit: The center focuses on Museums/ ancient African history dating as far back as 3 million years. Displays include animated robotic figures and Cultural videos that help educate visitors on the many civ- ilizations that originated on the continent. Attractions Location: 21511 W. McNichols, Detroit Mon.-Fri. 8 a.m.-3 p.m. Charles H. Wright Museum (313) 494-7452 or of African American History www.detpub.k12.mi.us/schools/AHCC/ You won’t find a bigger monument to African- The Burton Historical American history anywhere else in the world. Besides three exhibition galleries, the museum Collection/E. Azalia Hackley also houses a theater, a café and a gift store. Memorial Collection Reasons to visit: The Charles H. Wright The Detroit Public Library’s main branch Museum is the largest museum of African houses two of the country’s most extensive American history in the world. African-American historical collections. Before you enter through the brass doors take Reasons to visit: The Hackley Collection is a moment to admire the architecture which is an North America’s oldest source of historical infor- attraction of its own. mation on the careers of African Americans in Inside, the museum’s core exhibition takes the performing arts. This collection features rare visitors from the origins of African culture photographs and books, manuscripts, sheet through the horrors of the Middle Passage and music and memorabilia dating back to the mid- on to the modern day accomplishments and 19th century. -

How the Henry Ford Complex Manages Over 1,000 Shifts Daily

The Henry Ford CASE STUDY How The Henry Ford Complex Manages Over 1,000 Shifts CLIENT The Henry Ford Daily with Just 3 People LOCATION On a sprawling 92-plus-acre site in Dearborn, Michigan, more than 1.7 Dearborn, MI million visitors annually experience 300 years of American innovation, ingenuity, resourcefulness, and perseverance at the five attractions on WEBSITE thehenryford.org site: The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, historic Greenfield Village, the Ford Rouge Factory Tour, The Benson Ford Research Center, and The Henry Ford Giant Screen Experience. However, one American innovation that helps keep the popular attraction complex humming is not on public display. It’s ScheduleSource’s innovative workforce management software, which runs behind-the-scenes to ensure that the attractions are fully staffed for all of those visitors—from peak season in the summer and holidays to the off-season. “It’s a large complex site,” says Ann Marie Bernardi, senior manager for administration and scheduling in the guest services unit of The Henry Ford, who has worked at the museum for 38 years. “We need to make sure we have coverage for all our units—Guest Services, Contact Center, Food Service, and Security.” The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and Greenfield Village programs unit also incorporates ScheduleSource’s software in their operations daily. ScheduleSource’s TeamWork software was first introduced in the museum’s guest services unit, which handles all front of house ticketing and guest relations for the attractions, starting in late 2004. In addition to guest services, ScheduleSource now handles scheduling for food services (in the museum and village), security (a 24-hour operation), and the contact center (incoming calls, information and orders for tickets), as well as for all the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation interpreters, crafts demonstrators, train and Model T operators, and presenters in the Greenfield Village and Ford Rouge Factory Tour. -

The World's Premier Automotive Tour Experience

The World’s Premier Automotive Tour Experience Driving America exhibition in Henry Ford Museum Best-of Highlights Group Benefi ts Day 1 The Henry Ford: • Visit Henry Ford Museum • Free parking • Dinner/evening at MotorCity Casino Hotel • Motor coach greeters Day 2 • Complimentary admission for driver and escort • Breakfast or lunch at Hard Rock Cafe Detroit • Express group check-in • Shopping at Great Lakes Crossing Outlets Great Lakes Crossing Outlets: Pre-registered groups receive a Passport to Shopping for exclusive discounts Two-Day Road Trip at over 100 stores and restaurants in the mall, shopping Day 1 bags and complimentary lunch for the driver and group • Visit Henry Ford Museum and Greenfi eld Village leader. Register online at greatlakescrossingoutlets. (option to add village ride pass) com/visitors or by calling 1-877-SHOP-GLC. • Dinner/evening at MotorCity Casino Hotel Hard Rock Cafe: Complimentary motor coach parking. Day 2 Tour operator groups receive one complimentary meal • Breakfast or lunch at Hard Rock Cafe Detroit per 20 guests and bus drivers eat for free. • Shopping/lunch at Great Lakes Crossing Outlets MotorCity Casino Hotel: Complimentary on-site motor coach parking; Reward Play incentives for motor coach Three-Day Motor City Immersion passengers; at least a $25 Reward Play incentive per person, group leader bonus and additional $50 Reward Day 1 • Visit Greenfi eld Village Play incentive for group leader. • Dinner/evening at MotorCity Casino Hotel The Henry Ford Day 2 Contact: Vickie Evans • 313.982.6008 • Visit Ford -

Palmer Woods Centennial Gala

CELEBRATE! PALMER WOODS CENTENNIAL GALA Detroit Golf Club Saturday, September 19, 2015 Palmer Woods Centennial Logos s part of the Palmer Woods 100-Year Celebration, the Palmer Woods Centennial Committee sponsored a design competition to create a new visual logo for the Aneighborhood’s Centennial year. Artists were invited to submit their vision for a Centennial logo. The following artists submitted the winning logos: PHIL LEWIS – 1st Place Winner The winning logo was conceived by Phil Lewis, a lifelong Detroiter, Cass Tech graduate and recipient of a BFA from the Center for Creative Studies majoring in Illustration. “My mother used to say I was born with a paintbrush in my hand. Drawing was an escape for me,” remarks Phil. His natural ability was honed at Cass Tech under the tutelage of well known teachers such as Dr. Cledie Taylor, Marian Stephens and Irving Berg. Entering the contest to design a logo in celebration of the Palmer Woods Centennial was an easy decision for Phil. He loves the city of Detroit and considers Palmer Woods one of Detroit’s jewels. Even though he does not live in the neighborhood, he is good friends with residents and very aware of the community. Phil’s logo design was inspired by the beauty, history and character of the homes. Consequently, his logo effectively captures the spirit of our strong and beautiful community. Currently Phil is the owner of Phil Lewis Studio and a Digital Content Artist for MRM McCann Advertising. As the winning artist for the neighborhood contest, Phil’s logo is featured on banners that are be placed on light posts within and along the perimeter of the neighborhood. -

Detroit Greenways Study

Building the Riverfront Greenway The State of Greenway Investments Along the Detroit River The vision of a continuous greenway along future projects. In fact, many additional the Detroit River seemed like a dream only a projects are already in the planning and few years ago. But today, communities and design process. businesses in Greater Detroit are redefining their relationship to the river and champion- There is a growing desire to increase access ing linked greenways along its entire length to the Detroit River as communities and — from Lake St. Clair to Lake Erie, across to organizations work to overcome the historical Canada, and up key tributaries like the Rouge, separation from the river caused by a nearly Ecorse, and Huron rivers. continuous wall of commercial development. Now, trails and walkways are being Working in partnership with the Metropoli- incorporated along the river, improving the tan Affairs Coalition and other stakeholders, aesthetic appearance of the shoreline and the Greater Detroit American Heritage River reaping the resulting recreational, ecological, Initiative has identified linked greenways as and economic benefits. In its mission to one of its top six priorities. This report create linked riverfront greenways, the Greater presents 14 such projects, all of which have Detroit American Heritage River Initiative begun or been completed since June 1999. is actively partnering with the many organi- zations that share this vision, including the When all fourteen greenways projects are com- Greenways Initiative of the Community pleted, they will be unique destinations that Foundation for Southeastern Michigan, link open spaces, protect natural and cultural the Automobile National Heritage Area and resources, and offer many picturesque views the Canadian Heritage River Initiative. -

Detroit Media Guide Contents

DETROIT MEDIA GUIDE CONTENTS EXPERIENCE THE D 1 Welcome ..................................................................... 2 Detroit Basics ............................................................. 3 New Developments in The D ................................. 4 Destination Detroit ................................................... 9 Made in The D ...........................................................11 Fast Facts ................................................................... 12 Famous Detroiters .................................................. 14 EXPLORE DETROIT 15 The Detroit Experience...........................................17 Dearborn/Wayne ....................................................20 Downtown Detroit ..................................................22 Greater Novi .............................................................26 Macomb ....................................................................28 Oakland .....................................................................30 Itineraries .................................................................. 32 Annual Events ..........................................................34 STAYING WITH US 35 Accommodations (by District) ............................. 35 NAVIGATING THE D 39 Metro Detroit Map ..................................................40 Driving Distances ....................................................42 District Maps ............................................................43 Transportation .........................................................48 -

Links Away the Institution’S Forward to the Present Day

Gain perspective. Get inspired. Make history. THE HENRY FORD MAGAZINE - JUNE-DECEMBER 2019 | SPACESUIT DESIGN | UTOPIAN COMMUNITIES | CYBERFORMANCE | INSIDE THE HENRY FORD THE HENRY | INSIDE COMMUNITIES | CYBERFORMANCE DESIGN | UTOPIAN | SPACESUIT 2019 - JUNE-DECEMBER MAGAZINE FORD THE HENRY MAGAZINE JUNE-DECEMBER 2019 THE PUSHING BOUNDARIES ISSUE What’s the unexpected human story behind outerwear for outer space? UTOPIAN PAGE 28 OUTPOSTS OF THE ‘60S, ‘70S THE WOMEN BEHIND THEATER PERFORMED VIA DESKTOP THE HENRY FORD 90TH ANNIVERSARY ARTIFACT TIMELINE Gain perspective. Get inspired. Make history. THE HENRY FORD MAGAZINE - JUNE-DECEMBER 2019 | SPACESUIT DESIGN | UTOPIAN COMMUNITIES | CYBERFORMANCE | INSIDE THE HENRY FORD THE HENRY | INSIDE COMMUNITIES | CYBERFORMANCE DESIGN | UTOPIAN | SPACESUIT 2019 - JUNE-DECEMBER MAGAZINE FORD THE HENRY MAGAZINE JUNE-DECEMBER 2019 THE PUSHING BOUNDARIES ISSUE What’s the unexpected human story behind outerwear for outer space? UTOPIAN PAGE 28 OUTPOSTS OF THE ‘60S, ‘70S THE WOMEN BEHIND THEATER PERFORMED VIA DESKTOP THE HENRY FORD 90TH ANNIVERSARY ARTIFACT TIMELINE HARRISBURG PA HARRISBURG PERMIT NO. 81 NO. PERMIT PAID U.S. POSTAGE U.S. PRSRTD STD PRSRTD ORGANIZATION ORGANIZATION NONPROFIT NONPROFIT WHEN IT’S TIME TO SERVE, WE’RE ALL SYSTEMS GO. Official Airline of The Henry Ford. What would you like the power to do? At Bank of America we are here to serve, and listening to how people answer this question is how we learn what matters most to them, so we can help them achieve their goals. We had one of our best years ever in 2018: strong recognition for customer service in every category, the highest levels of customer satisfaction and record financial results that allow us to keep investing in how we serve you.