Tritrophic Interactions in Maize Storage Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life History of the Angoumois Grain Moth in Maryland

2 5 2 8 2 5 :~ Illp·8 11111 . 11111 11111 1.0 1.0 i~ . 3 2 Bkl: 1111/,32 2.2 .,lA 11111 . .2 I" 36 I" .z 11111 .: ~F6 I:' I'· "' I~ :: ~m~ I.: ,~ ~ l..;L,:,1.O. '- " 1.1 1.1 La.. , -- -- 11111 1.8 111111.25 /////1.4 111111.6 111111.25 1111/1.4 ~ 11111~·6 MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANOAROS-1963·A NATIONAL BUREAU Dr STAN£1AHOS·1963 A :1<f:~ . TEcliNICALBuLLETIN~~==~~.="=' No. 351 _ '='~.\III~.J.~=~.~=======_ APIUL, 1933 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE WASHINGTON. D. C. 'LIFE HISTORY. OF THE ANGOUMOI8. .. ~ GRAIN MOTH IN MARYLAND . • ~J:J By PEREZ SIMM;ONS, Entomologist; and G. W. ~LLINGTON,t Assi8tant Entomologist, . DiVision of StoTed Product In.~ecw, Bureau of Entomology 2 CONTENTS Page Page , :.. Introduction________________________________ 1 Lif",his.tor~OVIp05.lt""l <;letails-Contint:ed.______ ._______________________ ·16 " ~ The AngoumoL. grain moth in wheat and ."'~ ~ corn~ ___ ..... ___ ... ___ .. ________________________ 2 Incubatioll period______________________ 19 Larval period___________________ _________ 20 ::<l ."': Annual cycle of the moth on :Maryland 2 "" _ farms ____________ ,____________________ Pupal period____________________________ 24 f_.~ Ef,Tects of some farm practices on moth Development from hotching to emer· :Ji :',f Increasc._______________________________ 3 gencc_________________________________ 25 Overwintering of the insP.Ct..____________ 3 Effectstemperatl on development Ires ________________________ oC high and low "'_ 28 Spring dispcr.;al to growing wh~aL______ 5 ;.; Thewheat Angoumois________________________________ grain moth in seed _ Comparative rate oC development oC thfi Ii sexes _________________________________.:. 30 <': Dispersal to cornfields ________ ._________ _ 12 Parasit.es____________________________________ 31 ~ - Life-history details ________________________ _ Outbreaks, past and Cuture__________________ 31 Behavior of the adults ________ . -

BIOLOGY of the ANGOUMOIS GRAIN MOTH, SITOTROGA CEREALELLA (Oliver) on STORED RICE GRAIN in LABORATORY CONDITION

J. Asiat. Soc. Bangladesh, Sci. 39(1): 61-67, June 2013 BIOLOGY OF THE ANGOUMOIS GRAIN MOTH, SITOTROGA CEREALELLA (Oliver) ON STORED RICE GRAIN IN LABORATORY CONDITION T. AKTER, M. JAHAN1 AND M.S. I. BHUIYAN Department of Entomology, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh 1Department of Entomology, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh Abstract The experiment was conducted in the laboratory of the Department of Entomology, Sher- e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka during the period from May 2009 to April 2010 to study the biology of the Angoumois grain moth, Sitotroga cerealella (Oliver) in Bangladesh. The ovipositional period, incubation period, larval period, pre-pupal period and pupal period of Angoumois grain moth were 3.67 days, 5.5 days, 25.2 days, 3.0 days and 5.0 days, respectively; male and female longevity of moth were 8.0 and10 days, respectively. The lengths of all five larval instars were 1.0 ± 0.00, 2.0 ± 0.02, 4.0 ± 0.06, 5.0 ± 0.03 and 4.0 ± 0.06 mm, and the widths were 0.10 ± 0.0, 0.4 ± 0.0, 0.6 ± 0.01, 0.8 ± 0.02 and 1.0 ± 0.09 mm, respectively. The length and width of the pre-pupa and the pupa were 4.0 ± 0.02, 3.5 ± 0.01 mm and 1.20 ± 0.05, 1.50 ± 0.03 mm respectively. The length of male and female was 11.2 ± 0.09 and 12.07 ± 0.06 mm respectively. Key words: Biology, Angoumois grain moth, Sitotroga cerealella, Stored rice grain Introduction Angoumois grain moth, Sitotroga cerealella (Oliver) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) is a primary colonizer of stored grain in subtropical and warm temperate regions of the world. -

Insect Pests of Stored Grain Blog

Insect Pests of Stored Grain Insect Pest Population Potential • Insects are 1/16 to ½ inch depending on the species. • Large numbers insects in small amounts of debris. • 500 female insects • each female produces 200 offspring • 10 million insects in two generations. Adapted from the Penn State University Agronomy Guide Store Grain Insects Economic Damage • Lose up to 10% of the grain weight in a full storage bin • grain bin containing 30,000 bushels of corn valued at $3.00 per bushel would lose $9,000 • The loss does not include dockage or the cost of eliminating the insects from the grain. Adapted from the Penn State University Agronomy Guide Sampling for Bugs Looking for Bugs Docking screens can be used to separate beetles from the grain. Primary Stored Grain Feeders in NYS Weevils • Granary Weevil • Rice Weevil • Maize Weevil Beetles • Lesser Grain Borer Moths • Angoumois grain moth Weevils Have Snouts! Snout No Snout Gary Alpert, Harvard University, Bugwood.org Gary Alpert, Harvard University, Bugwood.org Maize Weevil Lesser Grain Borer Granary weevil Sitophilus granarius (L.) • polished, blackish or brown. • 3/16 of an inch long • no wings • Not in the field • longitudinal punctures- thorax • 80-300 eggs laid • One egg per grain kernel • corn, oats, barley, rye, and wheat Clemson University - USDA Cooperative Extension Slide Series , Bugwood.org Rice Weevil (Sitophilus oryzae) • 3/32 of an inch. • reddish brown to black • Small round pits-thorax • Has wings with yellow markings • Lays 80-500 eggs inside of grain • One egg per grain kernel • Start in the field • wheat, corn, oats, rye, Joseph Berger, Bugwood.org barley, sorghum, buckwheat, dried beans Maize Weevil Sitophilus zeamais • Very similar to rice weevil • slightly larger • 1/8 of an inch long • Small round pits on thorax with a mid line. -

Urban and Stored Products Entomology

Session 23 - URBAN AND STORED PRODUCTS ENTOMOLOGY [4018] ANALYSING mE IMPACT OF TERETRIUS NIGRESCENS ON [4020] NEAR-INFRARED SPECTROSCOPY APPLIED PROSTEPHANUS TRUNCATUS IN MAIZE STORES IN WEST AFRICA PARASITOIDS AND HIDDEN INSECT LARVAE, COLEOPTERA, AND CHRONOLOGICAL AGE-GRADING N. Holsl'. W. G. Meikle', C. Nansen' & R. H. Markham', 'Danish lnsl. of Agricultural Sciences, Aakkebjerg, 4200 Siagelse, Denmark, E-mail [email protected]; F. E. Dowell', J. E. Throne', A. B. Broce', R. A. Wirtz', J. Perez' & J, E. Baker', 2International Insl. of Tropical Agriculture, 08 B. P. 0932 Tri-postal, Cotonou, Benin. 'USDA ARS Grain Marketing and Production Res. Center, 1515 College Ave .. Manhattan, KS 66502, USA, E-mail [email protected]; 2Dept. of Entomol., Kansas Since its accidental introduction into East and West Africa in the early 1980's the larger State Univ., Manhattan, KS 66506; 'Entomo!. Branch, Division of Parasitic Diseases, grain borer, Prostephanus truncarus (Co!.: Bostrichidae), has been expanding its Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta; GA 30341. geographical range and is rapidly becoming the most serious pest on stored maize and cassava in the whole sub-Saharan region. In its wake, scientists and extension officers Near-infrared spectroscopy (NlRS) was used to detect parasitoids in insect-infested wheat have been releasing the predator Teretrius (Teretriosoma) nigrescens (Col.: Histeridae) as kernels or parasitoids in house fly puparia, to detect hidden insects in grain. to identify a means of biological control. Based on results obtained in the early 1990' s in the initial stored-grain Coleoptera, and to age-grade Diptera. In tests to detect parasitized rice area of release in Togo and Benin, T. -

PESTS of STORED PRODUCTS a 'Pest of Stored Products' Can Refer To

PESTS OF STORED PRODUCTS A ‘pest of stored products’ can refer to any organism that infests and damages stored food, books and documents, fabrics, leather, carpets, and any other dried or preserved item that is not used shortly after it is delivered to a location, or moved regularly. Technically, these pests can include microorganisms such as fungi and bacteria, arthropods such as insects and mites, and vertebrates such as rodents and birds. Stored product pests are responsible for the loss of millions of dollars every year in contaminated products, as well as destruction of important documents and heritage artifacts in homes, offices and museums. Many of these pests are brought indoors in items that were infested when purchased. Others originate indoors when susceptible items are stored under poor storage conditions, or when stray individual pests gain access to them. Storage pests often go unnoticed because they infest items that are not regularly used and they may be very small in size. Infestations are noticed when the pests emerge from storage, to disperse or sometimes as a result of crowding or after having exhausted a particular food source, and search for new sources of food and harborage. Unexplained occurrences of minute moths and beetles flying in large numbers near stored items, or crawling over countertops, walls and ceilings, powdery residues below and surrounding stored items, and stale odors in pantries and closets can all indicate a possible storage pest infestation. Infestations in stored whole grains or beans can also be detected when these are soaked in water, and hollowed out seeds rise to the surface, along with the adult stages of the pests, and other debris. -

Stored Product Pests

L-2046 2-02 Pantry and Fabric Pests in the Home Michael Merchant and Grady J. Glenn* often found on crape myrtles and other orna- ood and fabric pests can be found in nearly mental shrubs and flowers. Should they come every home. They are usually no more than indoors, carpet beetles or clothes moths may lay an occasional inconvenience. If an infesta- their eggs on woolen carpets or stored fabric Ftion develops in your home, the information in items. this publication should help you control it. Some insects feed primarily on plant materials Pests of seeds, grains and and are usually found in stored foods in kitchens and pantries. Other insects feed primarily on spices products containing animal proteins, such as The Indian meal moth is a common and dis- woolen fabrics, leather and hides, hair, feathers, tinctive pantry pest. It is the most common pest powdered milk and some pet foods. Animal of dried fruit, nuts, cereals and oilseeds. It also product pests are more likely to be found in infests powdered milk, chocolate and other can- closets and areas other than kitchens. Either kind dies, bird seed and dog food. The adult Indian of pest can be found almost anywhere in a home, meal moth has wings that are whitish-gray at the however. If you find the same kind of insect base and deep pink or copper colored on the repeatedly in a kitchen or closet it is good evi- outer two-thirds. The wingspan is about 3/4-inch. dence of a pest problem. The caterpillars, or immature stage of the Indian meal moth, are often noticed crawling up walls How did they get in my and spinning cocoons on textured walls or ceil- ings. -

STORED SEED INSECTS and THEIR CONTROL Stanley Coppock 11

STORED SEED INSECTS AND THEIR CONTROL Stanley Coppock 11 Primary Gra i n Insects There are only a few primary grain insects, that is, insects capa ble of destroying sound grain. The most important of the basic grain destroyers include the rice weevil, granary weevil, pea and bean wee vils, lesser grain borer and anguomois grain moth. Of these grain pests, the rice weevi l, lesser grain borer and pea and bean weev ils are the most widespread and also do the most damage to seed and commercial grain. The rice and granary weevils are simi lar in appearance and life histories and do the same kind of damage. However, the rice weevil is more important for it is capable of l aying eggs on the grain in the field. It also is capable of flight, whereas the granary weevi l is not. Both of these pests lay eggs, they then hatch and the young l arvae tunnel into the grain and devour its contents. Pea and bean weevi l s attack almost all seeds of the pea and bean family. Peas and beans may either be attacked in the field or in the granary. These insects are often insidious in that beans and peas may be infested in the field and not show that an infestation is present. Therefore, during the storage period heavy damage can be done to the seed. The lesser grain borer is perhaps the most widespread of our pri mary grain insects. In many states it is considerably more prevalent in stored grain and seeds than are the other weevils. -

Angoumois Grain Moth Introduction Recognition

ANGOUMOIS GRAIN MOTH INTRODUCTION The Angoumois grain moth is so named because it was first reported destroying grain in this French province. It is of worldwide distribution and was introduced into North Carolina in 1728 from Europe. In the United States, it is considered second only to granary and rice weevils as a pest of stored grain. RECOGNITION Adults with wingspread (wing tip to wing tip) about 1/2-5/8" (12-17 mm). Color buff to pale yellowish brown. Hind wings abruptly narrowed at tip towards front wing and fringed/margined with hairlike scales, about as long as wing is wide. Mature larva up to about 1/4" (7 mm) long. Color white with yellowish head and dark reddish-brown mouthparts. With 5 pairs of rudimentary (poorly developed) prolegs on abdomen, each with only 2 or 3 crochets (hooks). Body with primary setae (hairs) only, lacking tufted or secondary hairs. Perspiracular tubercle (wartlike area between spiracle and front edge of segment) on prothorax with 3 setae (hairs). BIOLOGY The female lays an average of 40 (range to 389) white eggs on or near grain. These turn red with age and hatch in 4-8 days. The 1st instar larva bores into a whole kernel and passes through a total of 3 instars in about 3 weeks, but may hibernate before pupation. It pupates within the hollowed-out kernel, and the pupal period lasts about 10-14 days. In warm climates the life cycle (egg to egg) usually requires 5-7 weeks, but may take 6 months in cool climates. -

Relative Biochemical Basis of Susceptibility in Commercial Wheat Varieties Against Angoumois Grain Moth, Sitotroga Cerealella

tri ome cs & Bi B f i o o l s t a a n t Safian Murad and Batool, J Biom Biostat 2017, 8:1 r i s u t i o c J s Journal of Biometrics & Biostatistics DOI: 10.4172/2155-6180.1000333 ISSN: 2155-6180 Research Article Article Open Access Relative Biochemical Basis of Susceptibility in Commercial Wheat Varieties against Angoumois Grain Moth, Sitotroga cerealella (Olivier) and Construction of its Life Table Safian Murad M1* and Batool Z2 1Department of Plant Protection, the University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Pakistan 2Department of Bioinformatics and Biotechnology, Govt. College University, Faisalabad Pakistan Abstract A study was conducted to evaluate the relative biochemical basis of susceptibility of six commercial wheat varieties grown in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, against angoumois grain moth, Sitotroga cerealella (Olivier) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) and construction of its life table at 28 ± 1°C, 65 ± 5 R.H.% and L:D 16:8 hours under laboratory environment. The results were evaluated on the basis of mean pest S. cerealella emergence, percent damage, and percent weight loss, male and female emerged along susceptibility index, 1000 grains weight, hardness and chemical composition of test wheat materials. Life table parameters of S. cerealella on highly susceptible and least susceptible wheat varieties were compared. On the basis of susceptibility index, variety Sirin (5.002) was recorded least susceptible and variety Pirsbak-2005 (7.832) recorded as highly susceptible. The chemical composition based on protein and carbohydrate contents (11.15%, 72.54%) revealed that the variety Sirin was recorded least susceptible, while variety Pirsabak-2005 (12.68%, 75.00%) was noted as highly susceptible. -

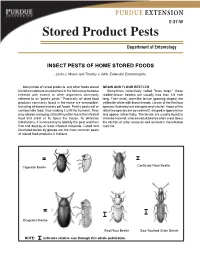

Stored Product Pests Department of Entomology

PURDUE EXTENSION E-37-W Stored Product Pests Department of Entomology INSECT PESTS OF HOME STORED FOODS Linda J. Mason and Timothy J. Gibb, Extension Entomologists Many kinds of cereal products and other foods stored GRAIN AND FLOUR BEETLES in kitchen cabinets or elsewhere in the home may become Sometimes collectively called "bran bugs," these infested with insects or other organisms commonly reddish-brown beetles are usually less than 1/8 inch referred to as "pantry pests." Practically all dried food long. Their small, wormlike larvae (growing stages) are products commonly found in the home are susceptible, yellowish-white with brown heads. Larvae of the first four including birdseed and dry pet foods. Pantry pests eat or species illustrated are elongate and tubular; those of the contaminate food, thus making it unfit for humans. They latter two species are somewhat C-shaped in appearance may also be annoying, in that they often leave the infested and appear rather hairy. The larvae are usually found in food and crawl or fly about the house. To eliminate infested material, whereas adult beetles often crawl about infestations, it is necessary to identify the pest and then the kitchen or other areas as well as feed in the infested find and destroy or treat infested materials. Listed and material. illustrated below by groups are the most common pests of stored food products in Indiana. Confused Flour Beetle Cigarette Beetle Drugstore Beetle Red Flour Beetle Saw-Toothed Grain Beetle NOTE: Indicates relative size through this whole publication Insect Pests of Home Stored Foods — E-37-W 2 DERMESTID BEETLES SPIDER BEETLES Members of this family are generally scavengers Several species of spider beetles (long legs and a and feed on a great variety of products of both plant general spider-like appearance) may be found infesting all and animal origin including leather, furs, skins, dried types of stored food products. -

GN 28 Itch Mites

No. 28 Replaces 04/94 Itch Mites By Darryl Hardie, Robert Emery, Entomology; Ken Adcock, Plant Pathology and Harald Hoffmann, Biosecurity Communications, South Perth This Gardennote is about skin itching on people caused by bites from species of itch mite. It does not include information on the scabies mite or allergic reactions from the faeces, dried bodies and skin casts of the European house dust mite or any other mite species. Itch mites are a problem when dried foodstuffs (such as fruits, seeds, cereal products, and pet food) infested with the larvae of storage insects are placed in warm, humid environments. The mites are also a common problem in haysheds that are exposed to rain-bearing winds in warm situations. Under these conditions large numbers of itch mites develop. Although the mites are primarily predators of soft-bodied insect larvae, they will also attack people and many domestic animals that come into contact with the infested material. Biology of itch mites The developmental stages of itch mites are egg, larvae, nymph, and adult. The life cycle usually takes two to four weeks but this depends on the mite species and weather. Female mites can lay 200 to 300 eggs. Itch mites are extremely small, normally being only 0.2 mm Figure 1. Pyemotes tritici straw itch mite (Photo by Eric Erbe; digital colourization by Chris Pooley, USDA) long, but a female engorged with eggs can reach 2 mm. The major hosts of itch mites are the larvae of several stored product pests such as the Angoumois grain moth, the saw-toothed grain beetle, the pea weevil, and the cowpea weevil. -

ANGOUMOIS GRAIN MOTH Doug Johnson, Extension Entomologist ENTFACT‐ 156 University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food, and Environment

INSECT PEST OF STORED GRAIN ANGOUMOIS GRAIN MOTH Doug Johnson, Extension Entomologist ENTFACT‐ 156 University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food, and Environment The Angoumois toothed grain beetle can coexist, but maize weevil or grain moth lesser grain borer will suppress AGM population. (AGM) can cause significant loss of Like most stored grain insects, AGM infestations can crib‐stored ear begin from adults emerging from small amounts of corn held for carry‐over corn in a crib. However, infestations can more than one also begin in the field from moths laying eggs before year. This insect harvest. The shuck provides protection against this is a primary insect. Nevertheless, moths can lay their eggs on stored grain pest kernels exposed due to a loose or damaged shuck. because its immature Life cycle (caterpillar) stages develop entirely within a grain AGM moths lay their eggs in the gaps between kernel. While AGM can attack several grains, it is kernels. Upon hatching, the tiny caterpillars most often associated with ear corn and is rare in immediately bore into a grain kernel, covering the shelled corn. An infested kernel is mostly hollow with hole after they enter. These larvae go through three a round hole through which the moth emerges. It will molts will feeding on the interior of the kernel. Just weigh about 20% less than a sound kernel. AGM‐ before pupating, the mature caterpillar chews a infested grain usually has an unpleasant odor so circular hole leaving a thin film over the future exit, animals may refuse to eat it or limit their through which the adult moth emerges.