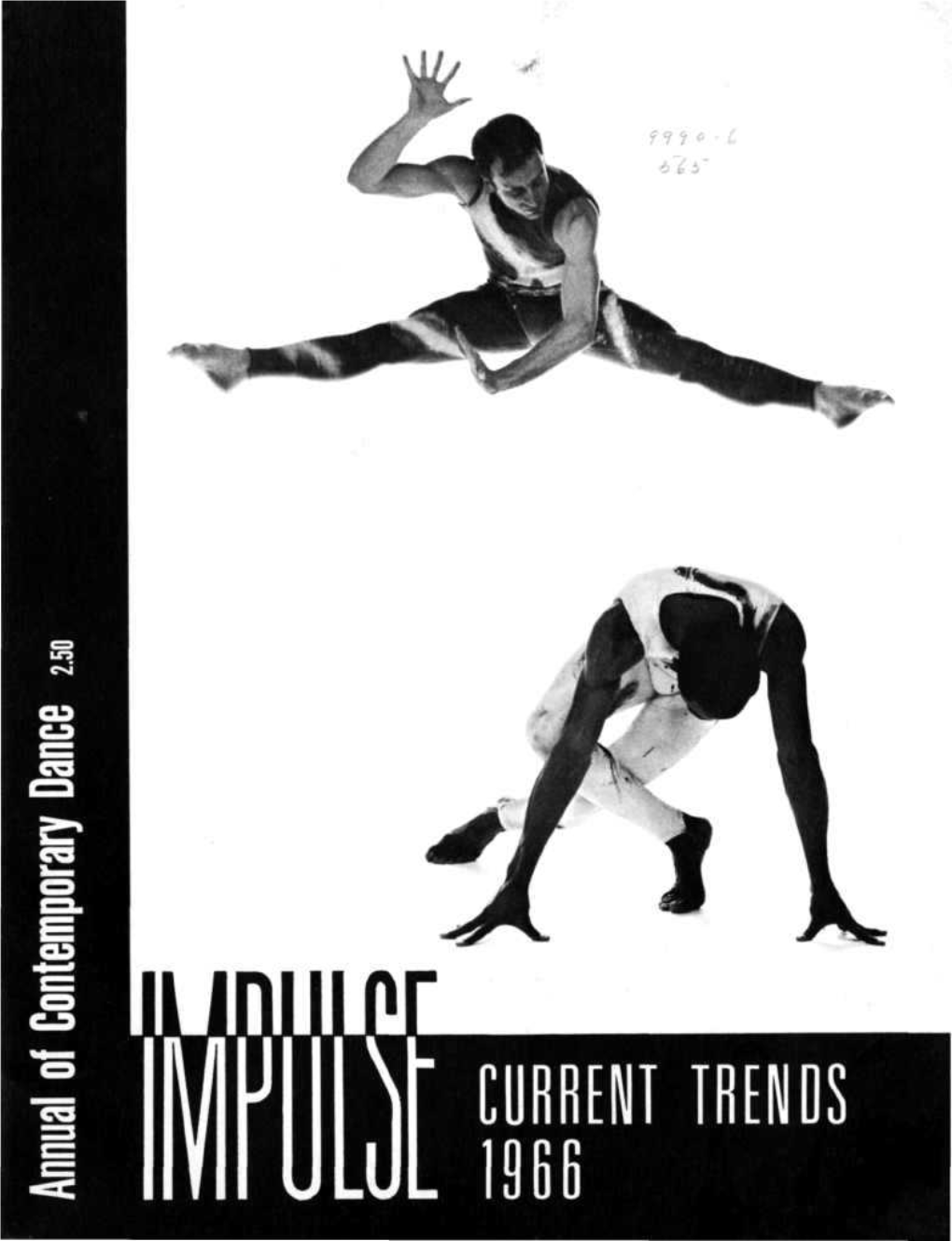

CURRENT TRENDS Copyright 1966 by Impulse Publications, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Danse Contemporaine En France Dans Les Années 1970

13-Annexe-VI:comite-histoire 30/05/07 17:55 Page 221 ANNEXE VI La danse contemporaine en France dans les années 1970 LES POINTS DE FRAGILITÉ La danse ne dispose pas d’institutions publiques autonomes Alors qu’existe déjà sur le territoire un réseau de centres dramatiques natio - naux, de maisons de la culture, de centres d’action culturelle dirigés presque exclusivement par des hommes de théâtre, alors que se constitue, conformément au plan de Marcel Landowski 1, un maillage du territoire en ce qui concerne les institutions musicales de diffusion et de formation (orchestres et conservatoires), les rares institutions de formation ou de dif - fusion chorégraphiques sont des entités insérées dans des théâtres lyriques 2 ou des conservatoires de musique dont aucun n’est dirigé par un danseur et qui n’ont ni budget autonome ni indépendance administrative. Ce domaine artistique n’a pas d’existence administrative propre Cette faiblesse du réseau institutionnel explique sans doute en partie le fait que le ministère de la Culture, au cours de l’individuation progressive des secteurs artistiques qui marque son évolution depuis 1959, n’ait pas éprou- vé le besoin de créer pour la danse de structure administrative spécifique. À la direction de la Musique, de l’Art lyrique et de la Danse (D MALD ), deux personnes seulement sont chargées – entre autres responsabilités – de l’en - 1. Nommé premier directeur de la Musique, de l’Art lyrique et de la Danse par André Bettencourt en décembre 1970, Marcel Landowski avait été auparavant chef du service de la musique (de 1966 à 1969), service rattaché à la direction générale des Arts et Lettres, puis chef du service de la musique, de l’art lyrique et de la danse (le terme n’apparaît qu’en 1969), service rattaché à la nou - velle direction des Spectacles, de la Musique et des Lettres 2. -

Méthode Pilates

COLLECTION SANTE MÉTHODE PILATES JUILLET 2017 Département Ressources professionnelles CN D 1, rue Victor-Hugo 93507 Pantin cedex 01 41 839 839 [email protected] cnd.fr Dans le cadre de sa mission d’information et d’accompagnement du secteur chorégraphique, le CND appréhende la santé comme une question faisant partie intégrante de la pratique professionnelle du danseur. À ce titre, il propose une information orientée autour de la prévention et de la sensibilisation déclinée sous forme de fiches pratiques. Cette collection santé s’articule autour de trois thématiques : nutrition, techniques corporelles ou somatiques et thérapies. Le CND a sollicité des spécialistes de chacun de ces domaines pour la conception et la rédaction de ces fiches. Bonne lecture Fiche réalisée en novembre 2010 pour le département Ressources professionnelles par Maxime Rigobert, danseur interprète et enseignant en danse contemporaine au CRR de Paris. Intéressé par les pratiques somatiques et thérapies manuelles, il est également praticien en Shiatsu et Ayurvéda. Maxime Rigobert tient à remercier Solange Mignoton, Dominique Dupuy et Dominique Praud pour leur précieuse aide. Les informations pratiques (texte de référence, bibliographie, webliographie, etc.) ont été mises à jour en juillet 2017. INTRODUCTION La méthode Pilates est une technique de travail du corps conçue, à l’origine, dans un but curatif et préventif des problèmes et accidents de la motricité. Elle fait partie des techniques d’éducation et de rééducation fonctionnelle qui regroupent aujourd'hui plusieurs approches visant à améliorer l'aisance du mouvement par le développement de la conscience corporelle. Aujourd’hui, la méthode Pilates est présente dans le monde entier et est devenue un terme générique au même titre que le yoga. -

The “Cunnin Gham Moment”

SITE DES ETUDES ET RECHERCHES EN DANSE A PARIS 8 THE “CUNNIN Sylviane PAGES GHAM MOMENT” THE EMERGENCE OF AN ESSENTIAL DANCE REFERENCE IN FRANCE Translated by Marisa Hayes from: « Le moment Cunningham. L'émergence d'une référence incontournable de la danse en France...», Repères - cahier de danse, avril 2009, p. 3-6. SITE DES ETUDES ET RECHERCHES EN DANSE A PARIS 8 THE Sylviane PAGES “CUNNINGHAM MOMENT” THE EMERGENCE OF AN ESSENTIAL DANCE REFERENCE IN FRANCE Translated by Marisa Hayes from: « Le moment Cunningham. L'émergence d'une référence incontournable de la danse en France...», Repères - cahier de danse, avril 2009, p. 3-6. Merce Cunningham’s reception in France is truly a “critical case study”: examining the press’ reactions to the choreographer allows us to highlight a history of consecration as much as it does an evolution of views and discourses on dance between the years of 1960 and 1980. In two decades--from the 1960s to the 1980s--Cunningham’s reception in France went from controversy to consecration, resulting in the almost overwhelming omnipresence of the choreographer. At the end of the 1970s and at the beginning of the 1980s, this success made Cunningham as much a source of attraction as it did a repellent during a time when dance in France was profoundly marked by the emergence of a new generation of choreographers named “jeune danse française” (young French dance). To be interested in Cunningham’s institutional reception and his impact on dancers’ imaginations and practices consists then in tracing the history of the emergence of this “new dance” in France, and studying what Cunningham “did” to contemporary dance. -

Download PDF Version

My Mary Personal Reminiscences of Learning from Wigman 1954–1959 and beyond Emma Lewis Thomas, January 2016 Mary Wigman ~ Photo: Orgel Kühne My Berlin: 1954 LUBSLUBSLUB… the bus sidled up to the curb in Charlottenburg, Berlin, S and stopped. A figure hurriedly descended the stairs from the upper level, and as the bus departed, stepped off and fell flat on the street. With cries from passengers, the bus stopped and the driver de- scended. (in German): “Why did you try to get off when the bus started?” he scolded.1 Regaining my breath and opening my eyes, I stammered, “This is my stop!” I got up, dusted myself off, and walked toward the apartment building where I had rented a room. This early memory of Berlin life recurs often—of living among disci- plined people on the politically free “island” of West Berlin—half a city arbitrarily slashed in two in 1947, occupied by British, French, and U.S. forces in the Western Sector; the other half, East Berlin, under Soviet Russian military control that extended beyond the city limits into the DDR (East Germany). Berlin-Ost, Berlin West. On each side, life was very different—but the people were the same: structured, organized, proud, helpful, forward-looking, disregarding (not discussing) the past. Because the Soviets, as Allies, “liberated” Berlin in 1945, they took the spoils. East Berlin occupied the center of the city: the beautiful Brandenburg Gate, Unter den Linden Boulevard, Potsdamer Platz, Humboldt University, Museum Island in the Spree River, the Berlin Opera, the Komische Oper, and the -

A Disconti Nuous and Transnatio Nal Historio Graphy

SITE DES ETUDES ET RECHERCHES EN DANSE A PARIS 8 RESURGENCE, TRANSFER AND TRAVELS Sylviane PAGES OF AN EXPRES SIONIST GESTURE: A DISCONTI NUOUS AND TRANSNATIO NAL HISTORIO GRAPHY. BUTO BETWEEN JAPAN, FRANCE AND Translated by Simon Pleasance from: "Ré- surgence, transfert et voyages d'un geste expressionniste en France : une historio- GERMANY graphie discontinue et transnationale. Le butô entre le Japon, la France et l'Alle- magne" in Isabelle Launay, Sylviane Pa- gès (dir.), Mémoires et histoire en danse, Mobiles n°2, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2010, p. 373-384. SITE DES ETUDES ET RECHERCHES EN DANSE A PARIS 8 RESURGENCE, TRANSFER AND TRAVELS OF AN EX Sylviane PAGES PRESSIONIST GESTURE: A DISCONTINUOUS AND TRANSNATIONAL HISTO RIOGRAPHY. BUTO BETWEEN JAPAN, FRANCE AND GERMANY1 Translated by Simon Pleasance from: "Ré- surgence, transfert et voyages d'un geste expressionniste en France : une historio- graphie discontinue et transnationale. Le butô entre le Japon, la France et l'Alle- magne" in Isabelle Launay, Sylviane Pa- gès (dir.), Mémoires et histoire en danse, Mobiles n°2, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2010, p. 373-384. Buto is a dance form which came into being in Japan in the 1950s and 1960s and was successfully introduced into France in the late 1970s. It immediately created a shock and a fascination, not without misunderstandings, among them its instant and systematic association with Hiroshima. We do not have the time here to deconstruct the buto stereotype “born in the ashes of Hiroshima”,2 but let us nonetheless point out that this dance, with its white, ghostlike and deformed bodies, has given rise to an interpretative shift from the macabre to mass death and, in France in the late 1970s, represented a memorial site for the tortuous and complex memory of the atomic explosions in Japan. -

Conversations Dance Studies

CONVERSATIONS ACROSS THE FIELD OF DANCE STUDIES Teacher’s Imprint—Rethinking Dance Legacy Society of Dance History Scholars 2017 | Volume XXXVII CONVERSATIONS ACROSS THE FIELD OF DANCE STUDIES Teacher’s Imprint—Rethinking Dance Legacy Society of Dance History Scholars 2017 | Volume XXXVII Table of Contents A Word from the Guest Editor | Contemporary Arts Pedagogy in India: Adishakti’s Sanja Andus L’Hotellier...................................................................... 6 “Source of Performance Energy” Workshop | Shanti Pillai ...................................................................................... 26 The Body of the Master (1993) followed by The Entity as Teacher—The Case for Canada’s National The Dance Master (In Question) (2017) | Choreographic Seminars | Dominique Dupuy .............................................................................. 8 Carol Anderson & Norma Sue Fisher-Stitt ....................................... 35 On Dance Pedagogy and Embodiment | Lost (and Found) in Transmission: Jessica Zeller................................................................................... 17 An Awakening of the Senses | Elizabeth Robinson.......................................................................... 40 Rethinking Pedagogy and Curriculum Models: Towards a Socially Conscious Afro-Cuban Dance Class | What Will Survive Us? Sigurd Leeder and His Legacy | Carolyn Pautz .................................................................................. 21 Clare Lidbury .................................................................................. -

Por Maxime Rigobert Colección Salud Noviembre 2014

CN D MÉTODO PILATES Por Maxime Rigobert Colección salud Noviembre 2014 Centre national de la danse Ressources professionnelles +33 (0)1 41 839 839 [email protected] cnd.fr En el marco de su misión de información y de acompañamiento del sector coreográfico, el CN D aborda la salud como una cuestión que forma parte integral de la práctica profesional de los bailarines. En esta óptica, ofrece una información orientada hacia la prevención y sensibilización, a través de fichas prácticas. Esta Colección Salud se articula en torno a tres temáticas: nutrición, técnicas corporales o somáticas y terapias. Para la concepción y redacción de dichas fichas, el CN D solicitó la colaboración de especialistas en cada uno de estos campos. Índice ¿Quién es Joseph Pilates? 3 ¿Cuándo y cómo llega el método a Francia? 4 ¿En qué consiste el método? 5 Descripción y principios de los ejercicios 6 ¿Cuáles son las aplicaciones terapéuticas? 7 ¿Quién puede practicarlo? 7 ¿Dónde formarse? 9 Para más información 12 Ficha realizada para el Departamento Recursos Profesionales en noviembre de 2010 por Maxime Rigobert, bailarín intérprete y profesor de danza contemporánea en el CRR de París. Maxime Rigobert se interesa en las prácticas somáticas y las terapias manuales; también practica Shiatsu y Ayurveda. Desea agradecer por su valiosa ayuda a Solange Mignoton, Dominique Dupuy y Dominique Praud. Las informaciones prácticas (texto de referencia, bibliografía, webliografía, etc.) se actualizaron en noviembre del 2014. 2 MÉTODO PILATES El método Pilates es una técnica de trabajo corporal concebida en su origen para curar y prevenir accidentes y problemas de motricidad. -

Aide À La Recherche Et Au Patrimoine En Danse 2016 Du CN D Mélanie Papin Et Guillaume Sintès

Aide à la recherche et au patrimoine en danse 2016 du CN D Mélanie Papin et Guillaume Sintès Wigman/Waehner : correspondances (1949-1972) CN D AIDE À LA RECHERCHE ET AU PATRIMOINE EN DANSE 2016 RÉSUMÉ DU PROJET « Wigman/Waehner : correspondances (1949-1972) », par Mélanie Papin et Guillaume Sintès [recherche appliquée] ORIGINE DU PROJET ET PREMIERS ÉLÉMENTS I. Origine du projet : pour une histoire de la danse contemporaine en France > Les projets d’un groupe de recherche En 2011, Sylviane Pagès, Mélanie Papin et Guillaume Sintès ont créé le Groupe de recherche : histoire contemporaine du champ chorégraphique en France. Accueilli par le Laboratoire d’analyse des discours et pratiques en danse (unité de recherches MUSIDANSE, université Paris 8), ce groupe émane d’un désir de mettre en commun les objets de recherche, les analyses et les débats, les questionnements et les documents qui produisent aujourd’hui des savoirs sur l’histoire contemporaine de la danse en France. Nous souhaitons ainsi valoriser et approfondir ce domaine de la recherche en danse encore peu développé. Si un chantier commun se dessine, il s’articule autour de perspectives multiples, complémentaires les unes par rapport aux autres. Ainsi, se croisent histoire culturelle et histoire juridique, pratique du studio et corporéité dansante, histoire sociale et esthétique. Depuis 2011, divers projets de recherche et de valorisation ont vu le jour. Entre 2012 et 2013, le groupe a organisé un cycle de journées d’étude intitulé « Relire les années 19701 ». La journée consacrée à Mai 68 s’est prolongée par la parution d’un ouvrage comprenant les témoignages mais aussi des entretiens, une chronologie et des analyses inédites. -

Méthode Pilates

CN D MÉTHODE PILATES Par Maxime Rigobert Fiche Santé Juillet 2017 Centre national de la danse Ressources professionnelles +33 (0)1 41 839 839 [email protected] cnd.fr Dans le cadre de sa mission d’information et d’accompagnement du secteur chorégraphique, le CN D appréhende la santé comme une question faisant partie intégrante de la pratique professionnelle du danseur. À ce titre, il propose une information orientée autour de la prévention et de la sensibilisation déclinée sous forme de fiches pratiques. Cette collection santé s’articule autour de trois thématiques : nutrition, techniques corporelles ou somatiques et thérapies. Le CN D a sollicité des spécialistes de chacun de ces domaines pour la conception et la rédaction de ces fiches. Sommaire Qui était Joseph Pilates ? 3 Quand et comment la méthode est-elle arrivée en France ? 4 En quoi consiste la méthode ? 5 Description et principes des exercices 6 Quelles sont les applications thérapeutiques ? 7 Qui peut exercer ? 7 Où se former ? 9 Bibliographie sélective 11 Fiche réalisée en novembre 2010 pour le département Ressources professionnelles par Maxime Rigobert, danseur interprète et enseignant en danse contemporaine au CRR de Paris. Intéressé par les pratiques somatiques et thérapies manuelles, il est également praticien en Shiatsu et Ayurvéda. Maxime Rigobert tient à remercier Solange Mignoton, Dominique Dupuy et Dominique Praud pour leur précieuse aide. Les informations pratiques (texte de référence, bibliographie, webliographie, etc.) ont été mises à jour en juillet 2017. 2 La méthode Pilates La méthode Pilates est une technique de travail du corps conçue, à l’origine, dans un but curatif et préventif des problèmes et accidents de la motricité.