Protein Requirements of the Elderly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

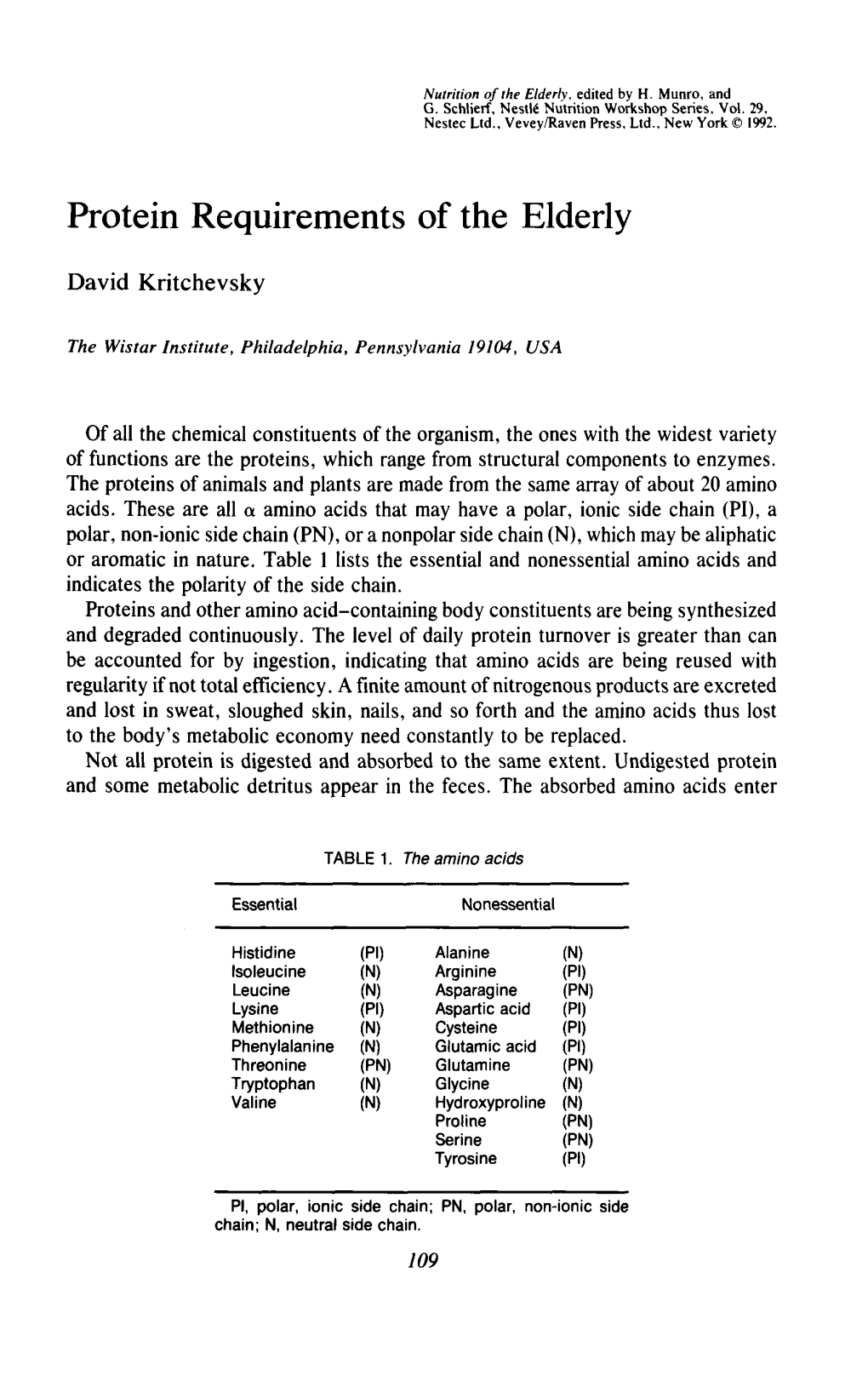

Recommended publications

-

Egg Consumption and Human Health

nutrients Egg Consumption and Human Health Edited by Maria Luz Fernandez Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Nutrients www.mdpi.com/journal/nutrients Egg Consumption and Human Health Special Issue Editor Maria Luz Fernandez MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Maria Luz Fernandez University of Connecticut USA Editorial Office MDPI AG St. Alban-Anlage 66 Basel, Switzerland This edition is a reprint of the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Nutrients (ISSN 2072-6643) in 2015–2016 (available at: http://www.mdpi.com/journal/nutrients/special issues/egg-consumption-human-health). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: Lastname, F.M.; Lastname, F.M. Article title. Journal Name. Year. Article number, page range. First Edition 2018 ISBN 978-3-03842-666-0 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03842-667-7 (PDF) Articles in this volume are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book taken as a whole is c 2018 MDPI, Basel, Switzerland, distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Table of Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... v Preface to ”Egg Consumption and Human Health” .......................... vii Jose M. Miranda, Xaquin Anton, Celia Redondo-Valbuena, Paula Roca-Saavedra, Jose A. -

Biological Value in Milk-Protein Concentrates with Malt Ingredients

─── Food Technology ─── Biological value in milk-protein concentrates with malt ingredients Olena Grek, Olena Onopriichuk, Alla Tymchuk National University of Food Technologies, Kyiv, Ukraine Abstract Keywords: Introduction. It is actual to study of biological value of milk-protein concentrates with malt ingredients. Biological Milk value characterizes the quality of the protein composition Protein with the ability to evaluate it according to physiological Malt norms. Amino acid Materials and methods. Milk protein concentrates without and with malt ingredients used for research. The biological value and amino acid composition of the samples was determined by ion exchange chromatography on LC Article history: 3000 automatic analyzer. Protein digestibility in vitro was Received 04.02.2019 determined by hydrolysis of samples using a solution of 6N Received in revised form hydrochloric acid at a temperature of (120 ± 2) ºС for 24 02.06.2019 hours. Accepted 30.09.2019 Results and discussion. The total amino acid content in milk protein concentrates with malt ingredients increased compared to control due to the addition of germinated Corresponding author: cereals (wheat, barley, oats, corn). The amino acid score for the studied samples has been Olena Onopriichuk calculated. When preparing the mixture: milk-protein E-mail: concentrate + malt ingredients, the content of limiting olena.onopriychuk@ amino acids increases – methionine + cystine and threonine. gmail.com Biological value of the experimental samples is increased. So, with wheat malt this indicator is 65.82%, barley – 65.57%, oat – 64.11%, corn – 63.95%, while for control purposes the value is fixed at 62.84%. The rationality coefficient of amino acid composition is 0.74±0.12, which is 3% higher than in milk protein concentrate obtained by traditional technology. -

Evaluation of Feeds for Protein

EVALUATION OF FEEDS FOR PROTEIN Dept of Animal Nutrition, CoVSc & AH, Jabalpur • Usefullness of feed as a source of protein depends on two factors – Total concentration of protein – Distribution of amino acids • Common methods Crude Protein True Protein “Stutzer’s reagent” Digestible Crude Protein In Non Ruminants 1. Weight gain Methods • Protein efficiency ratio • Net protein retention • Gross protein Value 2. Nitrogen Balance Experiments • Biological value • Net Protein utilization • Protein replacement value 3. Body nitrogen retention method 4. Chemical Evaluation of protein from AA composition • Chemical score • Essential amino acid index WEIGHT GAIN METHODS i) Protein efficiency ratio (PER): Weight gain per unit weight of protein consumed Gain in wt. PER = Protein intake PER of wheat flour – 1.2 & skimmed milk powder- 2.8 Limitation: Tedious Cannot assess digestibility of protein Weight gain may be due to bone or fat formation ii) Net protein retention (NPR): It is a modification of PER Weight gain of TPG - weight loss of NPG NPR= Protein intake TPG- group fed on test protein NPG- group fed on non protein diet iii) Gross protein value (GPV): Chicks fed 8% protein for 2 weeks After that divide into 3 groups 1st 80g CP/kg 2nd 80g CP/kg + 30g CP/kg of a test protein 3rd 80g CP/kg + 30g CP/kg of a casein g increased weight gain / g test protein GPV= g increased weight gain / g casein NITROGEN BALANCE EXPERIMENTS 1. Biological Value (BV): “Karl Thomas” It is proportion of the nitrogen absorbed which is retained by the animal. N intake – (FN+UN) % BV= X 100 N intake – FN This is apparent BV NI – (FN-MFN)-(UN-EUN) % BV= X 100 NI – (FN-MFN) This is True BV 2. -

Dietary Protein Quality Evaluation in Human Nutrition: Report of an FAO Expert Consultation

ISSN 0254-4725 FAO Dietary protein quality FOOD AND NUTRITION evaluation in human PAPER nutrition 92 Report of an FAO Expert Consultation FAO Dietary protein quality FOOD AND NUTRITION evaluation in PAPER human nutrition 92 Report of an FAO Expert Consultation 31 March–2 April, 2011 Auckland, New Zealand FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS ROME, 2013 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-107417-6 All rights reserved. FAO encourages reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. -

The Biological Value of Soybean in Relation to Protein And

THE BIOLOGICAL VALUE OF SOYBEAN IN RELATION TO PROTEIN AND CALCIUM AS REVEALED BY ANIMAL FEEDING • By EVELYN LANE WILLIAMS,, Bachelor of Science Mary Washington College Fredericksburg, Virginia 1941 Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State Univer~ity in partial fuli1lliilent of the requirements . for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE July, 1966 THE BIOLOGICAL VALUE OF SOYBEAN IN RELATION TO PROTEIN AND CALCIUM AS REVEALED BY ANIMAL FEEDING Thesis Approved: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express her sincere appreciation to: Dr. Helen F. Barbour; for her counsel, advice, and help in the formulation of the author's graduate program and invaluable assistance in the writing of this thesis and guiding the experimental work. Mr. and Mrs. L.• H. Wagner, wenderful friends, for advice and encouragement. Mrs. Carolyn Hackett for the typing of this .manuscript. Mrs. Alberta Lane, the author's mother for her regular corres pondence and encouragement during the lengtp of this graduate program.• The author wishes also to express her sincere appreciation to her husband, Douglass Williams, and children, Douglass, Judith, and Lane, for their kind forebearance during the time of graduate study and the· preparation of this manuscript. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION. ~ ·• ·• . ·• .. ' . 1 Statement of the Problem . .. .. 3 Assumptions , , • • O; ., ,o 5 Hypotheses . 5 II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE. 7 History of the Soybean • • • • • • • • • • • • 7 Composition of Protein •• 10 Composition of Soybeans • . , • • • • 14 Enzyme Inhibitors • • • • , • • • • 19 Preparation of Soybean Products. • 22 Biological Value of Soybeans • • • • ••• 27 Determination of Protein Deficiency ••• , • , • , , • 31 Functions of Calcium , , • , , •••••• , • , ••• 32 Determination of Calcium Deficiency 37 The Rat as an Experimental Animal •• 39 III. -

Nutritional Status and Cognitive Value of Egg White, Egg Yolk Whole Egg

Journal of Nutrition and Health Sciences Volume 8 | Issue 1 ISSN: 2393-9060 Review Article Open Access Nutritional Status and Cognitive Value of Egg White, Egg Yolk Whole Egg based Complementary Food Ibironke SI* Department of Food Science and Technology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria *Corresponding author: Ibironke SI, Department of Food Science and Technology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria, E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Ibironke SI (2021) Nutritional Status and Cognitive Value of Egg White, Egg Yolk Whole Egg based Complementary Food. J Nutr Health Sci 8(1): 101 Abstract Prominent among animal proteins, Eggs are one of the only foods that naturally contain vitamin D and Choline, that are essential for normal physiology, psychology reasoning and functioning of all children cells, but particularly important during pregnancy to support healthy brain development of the foetus and it is liking to a Mothers ‘breast milk. The purpose of the study was to investigate the nutritional status and Cognitive Value of Egg White, Egg Yolk and the Whole Egg based complementary Foods. The Composition of the weaning foods are as follow: Egg White10% basal 90 % (1), Egg Yolk 10 % Basal 90 % (2), Whole Egg10 % Basal 90 % (3), Control 100% Milk- based commercial diet (4), Basal 100% (5). The parameter examined were Growth response, Weight of Internal Organs (Endocrine), Nitrogen Retention and Biological Value of the experimental animals the results revealed that. Weight of Internal Organs (Endocrine), group of animal fed on diets 1-4 grew and increase in size expect for basal diet which could not could not promote increase in sizes of the organs. -

Fact Sheet PROTEIN and AMINO ACID SUPPLEMENTATION

fact sheet Protein and amino acid suPPLEMENTATION There is probably no other nutrient that has captured the of high value, so long as its anti-nutritional factors are removed. imagination of athletes more than protein. Recent interest in the While there are a large number of amino acids derived from the virtues of protein for both fat loss and muscle gain has ensured foods we eat, it is only the essential amino acids (ones our body athletes, both endurance and strength focused, to have taken a cannot make itself and thus must come from the diet) that are keener interest in their protein intake. This heightened interest required to facilitate many of the functions important to athletes. has also stimulated a flourishing protein supplement industry which has been very cleverly marketed. Given this, it shouldn’t The individual amino acids produced during the metabolism come as a surprise that protein and amino acid supplements of dietary proteins serve as both a substrate for building other remain some of the most popular dietary supplements among dietary proteins as well as a trigger for activating various athletes and fitness enthusiasts. metabolic processes. Amongst athletes interested in muscle hypertrophy, amino acids, and specifically leucine, play a critical Protein needs of athletes… is role in stimulating muscle protein synthesis. The leucine content of foods varies markedly but some foods are naturally high in suPPlementation warranted? leucine, including milk and meat proteins. Financial support of There is now little doubt that hard training athletes have higher the dairy industry has facilitated significant research into the protein needs than their sedentary counterparts, perhaps 50- value of dairy proteins. -

Soybean, Nutrition and Health

Chapter 20 Soybean, Nutrition and Health Sherif M. Hassan Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/54545 1. Introduction Soybean (Glycine max L.) is a species of legume native to East Asia, widely grown for its edi‐ ble bean which has several uses. This chapter will focuses on soybean nutrition and soy food products, and describe the main bioactive compounds in the soybean and their effects on human and animal health. 2. Soybean and nutrition Soybean is recognized as an oil seed containing several useful nutrients including pro‐ tein, carbohydrate, vitamins, and minerals. Dry soybean contain 36% protein, 19% oil, 35% carbohydrate (17% of which dietary fiber), 5% minerals and several other compo‐ nents including vitamins [1]. Tables 1 and 2 show the different nutrients content of soy‐ bean and its by-products [2] Soybean protein is one of the least expensive sources of dietary protein [3]. Soybean protein is considered to be a good substituent for animal protein [4], and their nutritional profile ex‐ cept sulfur amino acids (methionine and cysteine) is almost similar to that of animal protein because soybean proteins contain most of the essential amino acids required for animal and human nutrition. Researches on rats indicated that the biological value of soy protein is sim‐ ilar to many animal proteins such as casein if enriched with the sulfur-containing amino acid methionine [5]. According to the standard for measuring protein quality, Protein Di‐ gestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score, soybean protein has a biological value of 74, whole soybeans 96, soybean milk 91, and eggs 97[6]. -

The Nutritive Value of Proteins: General Considerations

ONE HUNDRED AND TWELFTH SCIENTIFIC MEETING ROYAL FREE HOSPITAL SCHOOL OF MEDICINE, 8 HUNTER STREET, LONDON, W.C.1 12 OCTOBER 1957 THE NUTRITIVE VALUE OF PROTEINS Chairman : DR D. P. CUTHBERTSON, C.B.E., M.D., D.Sc., F.R.S.E., Rowett Research Institute, Bucksburn, Aberdeenshire The nutritive value of proteins : general considerations By KATHLEENM. HENRYand S. K. KON,National Institute for Research in Dairying, Shinjield, near Reading Earlier concepts of nutrition divided proteins into those of first and those of second class, the former being of animal and the latter of vegetable origin. With increasing knowledge it became evident that the differences between foods as protein sources were reflecting differences in amino-acid composition and also that the superiority of ‘first class’ protein was often partly due to accompanying vitamins or minerals. We now know that this distinction between animal and vegetable proteins is neither rigid nor always justified. The value of a food as a source of protein is determined by the concentration of protein in it, the digestibility of the protein, the availability of its amino-acids for the synthesis of tissue protein, and its amino-acid pattern, particularly the content and proportions of the essential amino-acids. Digestibility and amino-acid pattern in turn determine the value of the food protein to the animal. There exist now many biological methods of scoring a protein on this basis, most of which confound these variables into one numerical expression. Bender (1958) deals with these methods in detail. All are designed for and capable of assigning to a protein a relative order of nutritional merit and thus all can be considered as measuring its biological value. -

Efficiency of Protein Utilization by Growing

EFFICIENCY OF PROTEIN UTILIZATION BY GROWING CHINCHILLA FED TWO LEVELS OF PROTEIN by JOHN CHARLES ROGIER B.Sc, University of British Columbia, 1965 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in the Department of Animal Science We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October, 1971 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of /A /Vwwi J k The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date iii ABSTRACT Six male and six female chinchilla (Chinchilla lanigera) in the late phase of growth were used to study the effects of sex, crude protein level in the ration and duration of experiment on body weight gains, digestibility of energy, dry matter, organic matter and protein and efficiency of protein utilization, as measured by biological value and net protein utilization. Two isocaloric rations of differing crude protein content (16.25% and 19.56%) were supplied ad libitum for three one-week experi• mental periods. The results showed that female chinchilla had significantly (P<0.05) greater body weight gains than males after adjustment for initial body weight and feed intake. -

Quality of Soybean Products in Terms of Essential Amino Acids Composition

molecules Article Quality of Soybean Products in Terms of Essential Amino Acids Composition Wanda Kudełka 1,* , Małgorzata Kowalska 2,* and Marzena Popis 1 1 Department of Quality Food Products, Cracov University of Economics, 31-510 Cracow, Poland; [email protected] 2 Department of Management and Product Quality, Faculty of Chemical Engineering and Commodity Science, Kazimierz Pulaski University of Technology and Humanities, 26-600 Radom, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected] (W.K.); [email protected] (M.K.) Abstract: The content of protein, moisture content and essential amino acids in conventional and genetically modified soybean grain and selected soybean products (soybean pâté, soybean drink, soybean dessert, tofu) was analyzed in this paper. The following comparative analysis of these products has not yet been carried out. No differences were observed in the amino acid profiles of soybeans and soybean products. The presence of essential amino acids was confirmed except for tryptophan. Its absence, however, may be due not to its absence in the raw material, but to its decomposition as a result of the acid hydrolysis of the sample occurring during its preparation for amino acid determination. Regardless of the type of soybean grain, the content of protein, moisture content and essential amino acids was similar (statistically insignificant difference). Thus, the type of raw material did not determine these parameters. There was a significant imbalance in the quantitative composition of essential amino acids in individual soybean products. Only statistically significant variation was found in genetically modified and conventional soybean pâté. Moreover, in each soy product their amount was lower irrespective of the raw material from which they were manufactured. -

Biological Value of Vegetable Proteins Available in Pakistan As Determined by Rat Feeding Experiment

BIOLOGICAL VALUE OF VEGETABLE PROTEINS AVAILABLE IN PAKISTAN AS DETERMINED BY RAT FEEDING EXPERIMENT By JAMEELA JAN Bachelor of Science University of Peshawar Peshawar,· West Pakistan 1962 Master of Science University of Punjab Lahore, West Pakistan 1964 Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate College - of the Oklahoma. State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 1967 ftlli•ttm•ffl,--A l... f .S~j.\:~'!y -l1JJW8 BIOLOGICAL VALUE OF VEGETABLE PROTEINS AVAILABLE IN PAKISTAN AS DETERMINED BY RAT FEEDING EXPERlMENT Thesis Approved: Thesis Adviser · n··n~ Dean of the Graduate College 058865 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express sincere appreciation and.grateful acknowledgement to her advisor, Dr. Helen F. Barbour for her keen interest, guidance and assistance during the course of this study. Thanks are extended to the Agricultural Research Service Station at New Orleans, Louisiana for their prompt service in providing cot ton seed flour for the experiment. The author is pleased to express her sincere thanks to the Govern ment of West Pakistan for providing her with a scholarship which en abled her to complete her studies. She also wishes to express her appreciation to her parents Dr. and Mrs. Jan Mohammad Khan for their understanding and patience dur ing her stay in the United States. Thanks are expressed to Mrs. E. Grace Peebles for her pains taking efforts in preparing this thesis for publication. iil TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE • • 5 Importance of Amino Acids and Proteins 5 Classification of Amino Acids with Respect -to Their Growth Effect • • • • • • • • 7 Composition of Proteins o • • • • • • • • • • • • lC The Structure of Protein • • • • 11 The Structure of Amino Acids • • • • • 12 Amino Acids and Protein Requirement ••••• 13 Protein Deficiencies in Developing Countries 19 Need for Protein Supplementation 22 Vegetable Protein Mixtures • • • • • • • • • 24 III.