A Report of a Probable Unprovoked Attack by an Australian Freshwater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

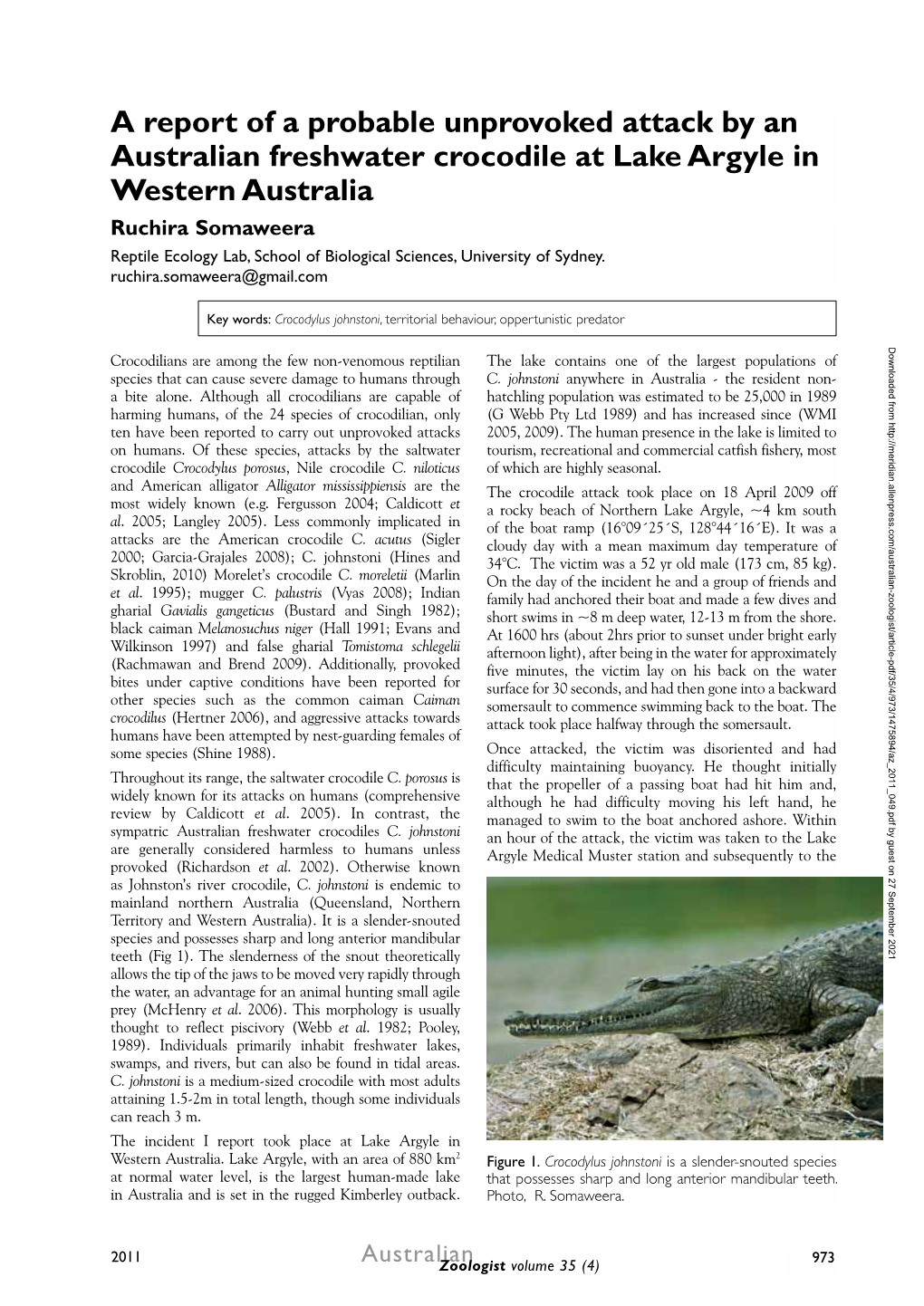

Crocodylus Johnstoni

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 33 103–107 (2018) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.33(1).2018.103-107 Observations of mammalian feeding by Australian freshwater crocodiles (Crocodylus johnstoni) in the Kimberley region of Western Australia Ruchira Somaweera1,*, David Rhind2, Stephen Reynolds3, Carla Eisemberg4, Tracy Sonneman5 and David Woods5 1 Ecosystem Change Ecology, CSIRO Land & Water, Floreat, Western Australia 6014, Australia. 2 School of Biological Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia. 3 Environs Kimberley, Broome, Western Australia 6725, Australia. 4 Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Northern Territory 0909, Australia. 5 Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions, West Kimberley District Offce, Broome, Western Australia 6725, Australia. * Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT – The dietary preference of most crocodilians is generally thought to be fairly broad. However, the head morphology of slender-snouted crocodilians limits their ability to process large and complex prey. The slender-snouted Australian freshwater crocodile is known to be a dietary specialist consuming small aquatic prey, particularly aquatic arthropods and fsh. Here, we report observations of predation events by Australian freshwater crocodiles on medium- and large-sized mammals in the Kimberley region of Western Australia including macropods, a large rodent and an echidna. We discuss the signifcance of our observations from an ecological and morphological perspective and propose that terrestrial mammalian prey may be a seasonally important prey item for some populations of freshwater crocodiles. KEYWORDS: mammal, marsupial, monotreme, predation INTRODUCTION occupying downstream estuarine areas (Cogger 2014; Crocodilians are opportunistic predators that capture Webb et al. 1983). Given the smaller size and the mild and consume a range of prey items usually associated temperament, attacks by this species on humans are with or attracted to water. -

Using Environmental DNA to Detect Estuarine Crocodiles, a Cryptic

Human–Wildlife Interactions 14(1):64–72, Spring 2020 • digitalcommons.usu.edu/hwi Using environmental DNA to detect estuarine crocodiles, a cryptic-ambush predator of humans Alea Rose, Research Institute for Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Northern Territory 0909, Australia Yusuke Fukuda, Department of Environment & Natural Resources, Northern Territory Govern- ment, P.O. Box 496, Palmerston, Northern Territory 0831, Australia Hamish A. Campbell, Research Institute of Livelihoods and the Environment, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Northern Territory 0909, Australia [email protected] Abstract: Negative human–wildlife interactions can be better managed by early detection of the wildlife species involved. However, many animals that pose a threat to humans are highly cryptic, and detecting their presence before the interaction occurs can be challenging. We describe a method whereby the presence of the estuarine crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), a cryptic and potentially dangerous predator of humans, was detected using traces of DNA shed into the water, known as environmental DNA (eDNA). The estuarine crocodile is present in waterways throughout southeast Asia and Oceania and has been responsible for >1,000 attacks upon humans in the past decade. A critical factor in the crocodile’s capability to attack humans is their ability to remain hidden in turbid waters for extended periods, ambushing humans that enter the water or undertake activities around the waterline. In northern Australia, we sampled water from aquariums where crocodiles were present or absent, and we were able to discriminate the presence of estuarine crocodile from the freshwater crocodile (C. johnstoni), a closely related sympatric species that does not pose a threat to humans. -

Human-Crocodile Conflict in Solomon Islands

Human-crocodile conflict in Solomon Islands In partnership with Human-crocodile conflict in Solomon Islands Authors Jan van der Ploeg, Francis Ratu, Judah Viravira, Matthew Brien, Christina Wood, Melvin Zama, Chelcia Gomese and Josef Hurutarau. Citation This publication should be cited as: Van der Ploeg J, Ratu F, Viravira J, Brien M, Wood C, Zama M, Gomese C and Hurutarau J. 2019. Human-crocodile conflict in Solomon Islands. Penang, Malaysia: WorldFish. Program Report: 2019-02. Photo credits Front cover, Eddie Meke; page 5, 11, 20, 21 and 24 Jan van der Ploeg/WorldFish; page 7 and 12, Christina Wood/ WorldFish; page 9, Solomon Star; page 10, Tessa Minter/Leiden University; page 22, Tingo Leve/WWF; page 23, Brian Taupiri/Solomon Islands Broadcasting Corporation. Acknowledgments This survey was made possible through the Asian Development Bank’s technical assistance on strengthening coastal and marine resources management in the Pacific (TA 7753). We are grateful for the support of Thomas Gloerfelt-Tarp, Hanna Uusimaa, Ferdinand Reclamado and Haezel Barber. The Ministry of Environment, Climate Change, Disaster Management and Meteorology (MECDM) initiated the survey. We specifically would like to thank Agnetha Vave-Karamui, Trevor Maeda and Ezekiel Leghunau. We also acknowledge the support of the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources (MFMR), particularly Rosalie Masu, Anna Schwarz, Peter Rex Lausu’u, Stephen Mosese, and provincial fisheries officers Peter Bade (Makira), Thompson Miabule (Choiseul), Frazer Kavali (Isabel), Matthew Isihanua (Malaita), Simeon Baeto (Western Province), Talent Kaepaza and Malachi Tefetia (Central Province). The Royal Solomon Islands Police Force shared information on their crocodile destruction operations and participated in the workshops of the project. -

Human-Wildlife Conflict in Africa

ISSN 0258-6150 157 FAO FORESTRY PAPER 157 Human-wildlife conflict in Africa Causes, consequences Human-wildlife conflict in Africa – Causes, consequences and management strategies and management strategies FAO FAO Cover image: The crocodile is the animal responsible for the most human deaths in Africa Fondation IGF/N. Drunet (children bathing); D. Edderai (crocodile) FAO FORESTRY Human-wildlife PAPER conflict in Africa 157 Causes, consequences and management strategies F. Lamarque International Foundation for the Conservation of Wildlife (Fondation IGF) J. Anderson International Conservation Service (ICS) R. Fergusson Crocodile Conservation and Consulting M. Lagrange African Wildlife Management and Conservation (AWMC) Y. Osei-Owusu Conservation International L. Bakker World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)–The Netherlands FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2009 5IFEFTJHOBUJPOTFNQMPZFEBOEUIFQSFTFOUBUJPOPGNBUFSJBMJOUIJTJOGPSNBUJPO QSPEVDUEPOPUJNQMZUIFFYQSFTTJPOPGBOZPQJOJPOXIBUTPFWFSPOUIFQBSU PGUIF'PPEBOE"HSJDVMUVSF0SHBOJ[BUJPOPGUIF6OJUFE/BUJPOT '"0 DPODFSOJOHUIF MFHBMPSEFWFMPQNFOUTUBUVTPGBOZDPVOUSZ UFSSJUPSZ DJUZPSBSFBPSPGJUTBVUIPSJUJFT PSDPODFSOJOHUIFEFMJNJUBUJPOPGJUTGSPOUJFSTPSCPVOEBSJFT5IFNFOUJPOPGTQFDJGJD DPNQBOJFTPSQSPEVDUTPGNBOVGBDUVSFST XIFUIFSPSOPUUIFTFIBWFCFFOQBUFOUFE EPFT OPUJNQMZUIBUUIFTFIBWFCFFOFOEPSTFEPSSFDPNNFOEFECZ'"0JOQSFGFSFODFUP PUIFSTPGBTJNJMBSOBUVSFUIBUBSFOPUNFOUJPOFE *4#/ "MMSJHIUTSFTFSWFE3FQSPEVDUJPOBOEEJTTFNJOBUJPOPGNBUFSJBMJOUIJTJOGPSNBUJPO QSPEVDUGPSFEVDBUJPOBMPSPUIFSOPODPNNFSDJBMQVSQPTFTBSFBVUIPSJ[FEXJUIPVU -

Master of the Marsh Information for Cart

Mighty MikeMighty Mike:Mike: The Master of the Marsh A story of when humans and predators meet Alligators are magnificent predators that have lived for millions of years and demonstrate amazing adaptations for survival. Their “recent” interaction with us demonstrates the importance of these animals and that we have a vital role to play in their survival. Primary Exhibit Themes: 1. American Alligators are an apex predator and a keystone species of wetland ecosystems throughout the southern US, such as the Everglades. 2. Alligators are an example of a conservation success story. 3. The wetlands that alligators call home are important ecosystems that are in need of protection. Primary Themes and Supporting Facts 1. Alligators are an apex predator and, thus, a keystone species of wetland ecosystems throughout the southern US, such as the Everglades. a. The American Alligator is known as the “Master of the Marsh” or “King of the Everglades” b. What makes a great predator? Muscles, Teeth, Strength & Speed i. Muscles 1. An alligator has the strongest known bite of any land animal – up to 2,100 pounds of pressure. 2. Most of the muscle in an alligators jaw is intended for biting and gripping prey. The muscles for opening their jaws are relatively weak. This is why an adult man can hold an alligators jaw shut with his bare hands. Don’t try this at home! ii. Teeth 1. Alligators have up to 80 teeth. 2. Their conical teeth are used for catching the prey, not tearing it apart. 3. They replace their teeth as they get worn and fall out. -

The Saltwater Crocodile, Crocodylus Porosus Schneider, 1801, in the Kimberley Coastal Region

Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia, 94: 407–416, 2011 The Saltwater Crocodile, Crocodylus porosus Schneider, 1801, in the Kimberley coastal region V Semeniuk1, C Manolis2, G J W Webb2,4 & P R Mawson3 1 V & C Semeniuk Research Group 21 Glenmere Rd., Warwick, WA 6024 2 Wildlife Management International Pty. Limited PO Box 530, Karama, NT 0812 3 Department of Environment & Conservation Locked Bag 104, Bentley D.C., WA 6983 4 School of Environmental Research, Charles Darwin University, NT 0909 Manuscript received April 2011; accepted April 2011 Abstract The Australian Saltwater Crocodile, Crocodylus porosus, is an iconic species of the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Biogeographically, it is distributed in the Indo-Pacific region and extends to northern Australia, with Australia representing the southernmost range of the species. In Western Australia C. porosus now extends to Exmouth Gulf. In the Kimberley region, C. porosus is found in most of the major river systems and coastal waterways, with the largest populations in the rivers draining into Cambridge Gulf, and the Prince Regent and Roe River systems. The Kimberly region presents a number of coastlines to the Saltwater Crocodile. In the Cambridge Gulf and King Sound, there are mangrove-fringed or mangrove inhabited tidal flats and tidal creeks, that pass landwards into savannah flats, providing crocodiles with a landscape and seascape for feeding, basking and nesting. The Kimberley Coast is dominantly rocky coasts, rocky ravines/ embayments, sediment-filled valleys with mangroves and tidal creeks, that generally do not pass into savannah flats, and areas for nesting are limited. Since the 1970s when the species was protected, the depleted C. -

Crocodile Facts and Figures

Crocodile facts The saltwater crocodile is the largest living reptile species. It can grow up to six metres and is a serious threat to humans. Saltwater crocodiles have evolved special characteristics that make them excellent predators. • Large saltwater crocodiles can stay underwater for at least one hour because they can reduce their heart rate to 2-3 beats per minute. This means that crocodiles can wait underwater until they see prey, or if people are using the same spot regularly, the crocodile can wait underwater until someone approaches the water’s edge. • A crocodile can float with only eyes and nostrils exposed, enabling it to approach prey without being detected. • When under water, a special transparent eyelid protects the crocodile’s eye. This means that crocodiles can still see when they are completely submerged. • The tail of a crocodile is solid muscle and a major source of power, making it a strong swimmer and able to make sudden lunges out of the water to capture prey. These strong muscles also mean that for shorts bursts of time crocodiles can move faster than humans can on land. • Crocodiles have a thin layer of guanine crystals behind their retina. This intensifies images, allowing crocodiles to see better at low light levels. • Crocodiles have a ‘minimum exposure’ posture in the water, which means that only their sensory organs of eyes, cranial platform, ears and nostrils remain out of the water. This means that they often go unseen by prey, but if they are observed, the prey is often not able to tell how big the crocodile is. -

Fauna of Australia 2A

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 39. GENERAL DESCRIPTION AND DEFINITION OF THE ORDER CROCODYLIA Harold G. Cogger 39. GENERAL DESCRIPTION AND DEFINITION OF THE ORDER CROCODYLIA Pl. 9.1. Crocodylus porosus (Crocodylidae): the salt water crocodile shows pronounced sexual dimorphism, as seen in this male (left) and female resting on the shore; this species occurs from the Kimberleys to the central east coast of Australia; see also Pls 9.2 & 9.3. [G. Grigg] Pl. 9.2. Crocodylus porosus (Crocodylidae): when feeding in the water, this species lifts the tail to counter balance the head; see also Pls 9.1 & 9.3. [G. Grigg] 2 39. GENERAL DESCRIPTION AND DEFINITION OF THE ORDER CROCODYLIA Pl. 9.3. Crocodylus porosus (Crocodylidae): the snout is broad and rounded, the teeth (well-worn in this old animal) are set in an irregular row, and a palatal flap closes the entrance to the throat; see also Pls 9.1 & 9.2. [G. Grigg] 3 39. GENERAL DESCRIPTION AND DEFINITION OF THE ORDER CROCODYLIA Pl. 9.4. Crocodylus johnstoni (Crocodylidae): the freshwater crocodile is found in rivers and billabongs from the Kimberleys to eastern Cape York; see also Pls 9.5–9.7. [G.J.W. Webb] Pl. 9.5. Crocodylus johnstoni (Crocodylidae): the freshwater crocodile inceases its apparent size by inflating its body when in a threat display; see also Pls 9.4, 9.6 & 9.7. [G.J.W. Webb] 4 39. GENERAL DESCRIPTION AND DEFINITION OF THE ORDER CROCODYLIA Pl. 9.6. Crocodylus johnstoni (Crocodylidae): the freshwater crocodile has a long, slender snout, with a regular row of nearly equal sized teeth; the eyes and slit-like ears, set high on the head, can be closed during diving; see also Pls 9.4, 9.5 & 9.7. -

Using Scat to Estimate Body Size in Crocodilians: Case Studies of the Siamese Crocodile and American Alligator with Practical Applications

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 15(2):325–334. Submitted: 19 December 2019; Accepted: 24 May 2020; Published: 31 August 2020. USING SCAT TO ESTIMATE BODY SIZE IN CROCODILIANS: CASE STUDIES OF THE SIAMESE CROCODILE AND AMERICAN ALLIGATOR WITH PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS STEVEN G. PLATT1, RUTH M. ELSEY2, NICHOLE D. BISHOP3, THOMAS R. RAINWATER4,8, OUDOMXAY THONGSAVATH5, DIDIER LABARRE6, AND ALEXANDER G. K. MCWILLIAM5,7 1Wildlife Conservation Society-Myanmar Program, No. 12, Nanrattaw Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon, Myanmar 2Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge, 5476 Grand Chenier Highway, Grand Chenier, Louisiana 70643, USA 3School of Natural Resources and Environment, Building 810, 1728 McCarthy Drive, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611-0485, USA 4Tom Yawkey Wildlife Center & Belle W. Baruch Institute of Coastal Ecology and Forest Science, Clemson University, Post Office Box 596, Georgetown, South Carolina 29442, USA 5Wildlife Conservation Society-Lao Program, Post Office Box 6712, Vientiane, Laos 6Départment de Biologie, Faculté des Sciences, Université de Sherbrooke, 2500 Boulevard de l’Université, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada 7Current address: International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), 63 Sukhumvit Road, Soi 39 Klongton-Nua, Bangkok, Thailand, 10110 8Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract.—Models relating morphological measures to body size are of great value in crocodilian research and management. Although scat morphometrics are widely used for estimating the body size of large mammals, these relationships have not been determined for any crocodilian. To this end, we collected scats from Siamese Crocodiles (Crocodylus siamensis) and American Alligators (Alligator mississippiensis) to determine if maximum scat diameter (MSD) could be used to predict total length (TL) in these species. -

The Eye of the Crocodile

The Eye of the Crocodile The Eye of the Crocodile Val Plumwood Edited by Lorraine Shannon Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Plumwood, Val. Title: The Eye of the crocodile / Val Plumwood ; edited by Lorraine Shannon. ISBN: 9781922144164 (pbk.) 9781922144171 (ebook) Notes Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Predation (Biology) Philosophy of nature. Other Authors/Contributors: Shannon, Lorraine. Dewey Number: 591.53 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image supplied by Mary Montague of Montague Leong Designs Pty Ltd. http://www.montagueleong.com.au Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Preface . ix Introduction . 1 Freya Mathews, Kate Rigby, Deborah Rose First section 1 . Meeting the predator . 9 2 . Dry season (Yegge) in the stone country . 23 3 . The wisdom of the balanced rock: The parallel universe and the prey perspective . 35 Second section 4 . A wombat wake: In memoriam Birubi . 49 5 . ‘Babe’: The tale of the speaking meat . 55 Third section 6 . Animals and ecology: Towards a better integration . 77 7 . Tasteless: Towards a food-based approach to death . 91 Works cited . 97 v Acknowledgements The editor wishes to thank the following for permission to use previously published material: A version of Chapter One was published as ‘Being Prey’ in Terra Nova, Vol. -

Crocodile Science

Crocodile science How old is the crocodile? Crocodiles have been around for 200 million years, and are a descendant from the dinosaur age. What is the full taxonomic name for the saltwater crocodile? Kingdom: Animalia (Animals) Phylum: Chordata (Chordates) Class: Reptilia (Reptiles) Order: Crocodylia (Crocodiles, Alligators, Gharials and Caimans) Family: Crocodylidae (Crocodiles and Relatives) Genus: Crocodylus Species: porosus What are the physical features of the crocodile? The Australian saltwater crocodile is one of the most aggressive and dangerous crocodiles. It is also the largest living reptile, exceeding the Komodo dragon in size. Sexual dimorphism (difference) is present in this species, with the females normally growing to more than 3 metres and males normally up to 6 metres. Crocodiles up to 10 metres have been recorded in the wild in the past, but are extremely rare. Saltwater crocodiles have very large heads. A pair of ridges runs from the eyes along the centre of the snout. The eyes, ears and nostrils are located on the same plane on the top of the head, allowing it to see, hear and breathe while almost totally submerged. The eyes have a special second pair of eyelids known as the nictitating membrane. These eyelids are clear and protect the eyes while underwater. The ears, situated behind the eyes, have flaps which also close while underwater. The jaws are heavyset and contain 64-68 teeth. The teeth in the upper jaw are perfectly aligned with those in the lower jaw. The fourth tooth on each side of the bottom jaw is larger than the other teeth and is visible when the mouth is closed. -

Oral and Cloacal Microflora of Wild Crocodiles Crocodylus Acutus and C

Vol. 98: 27–39, 2012 DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Published February 17 doi: 10.3354/dao02418 Dis Aquat Org Oral and cloacal microflora of wild crocodiles Crocodylus acutus and C. moreletii in the Mexican Caribbean Pierre Charruau1,*, Jonathan Pérez-Flores2, José G. Pérez-Juárez2, J. Rogelio Cedeño-Vázquez3, Rebeca Rosas-Carmona3 1Departamento de Zoología, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Distrito Federal 04510, Mexico 2Departamento de Salud y Bienestar Animal, Africam Safari Zoo, Puebla, Puebla 72960, Mexico 3Departamento de Ingeniería Química y Bioquímica, Instituto Tecnológico de Chetumal, Chetumal, Quintana Roo 77013, Mexico ABSTRACT: Bacterial cultures and chemical analyses were performed from cloacal and oral swabs taken from 43 American crocodiles Crocodylus acutus and 28 Morelet’s crocodiles C. moreletii captured in Quintana Roo State, Mexico. We recovered 47 bacterial species (28 genera and 14 families) from all samples with 51.1% of these belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae. Fourteen species (29.8%) were detected in both crocodile species and 18 (38.3%) and 15 (31.9%) species were only detected in American and Morelet’s crocodiles, respectively. We recovered 35 bacterial species from all oral samples, of which 9 (25.8%) were detected in both crocodile species. From all cloacal samples, we recovered 21 bacterial species, of which 8 (38.1%) were detected in both crocodile species. The most commonly isolated bacteria in cloacal samples were Aeromonas hydrophila and Escherichia coli, whereas in oral samples the most common bacteria were A. hydrophila and Arcanobacterium pyogenes. The bacteria isolated represent a potential threat to crocodile health during conditions of stress and a threat to human health through crocodile bites, crocodile meat consumption or carrying out activities in crocodile habitat.