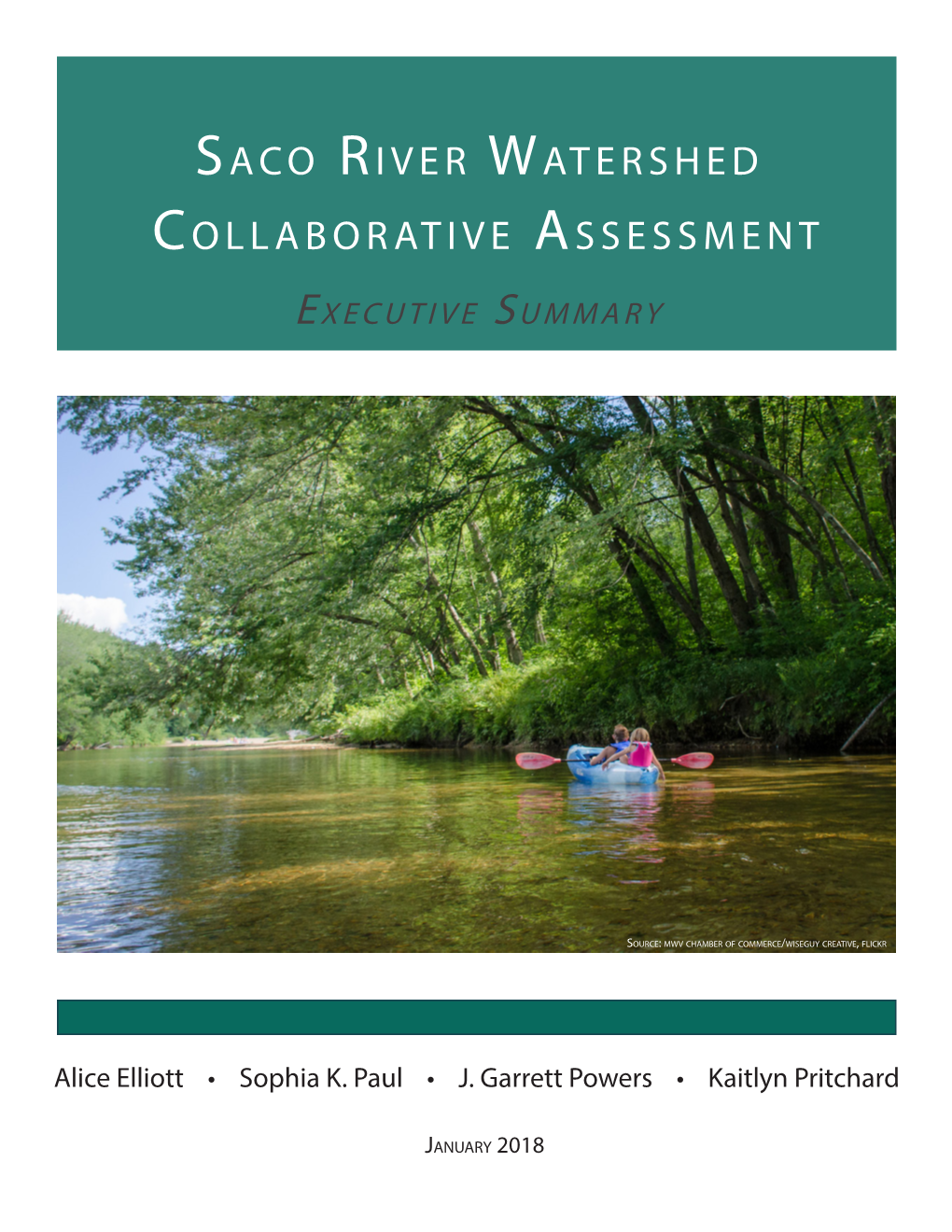

Saco River Watershed Collaborative Assessment”, Will Be Available in February 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saco River Saco & Biddeford, Maine

Environmental Assessment Finding of No Significant Impact, and Section 404(b)(1) Evaluation for Maintenance Dredging DRAFT Saco River Saco & Biddeford, Maine US ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS New England District March 2016 Draft Environmental Assessment: Saco River FNP DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FINDING OF NO SIGNIFICANT IMPACT Section 404(b)(1) Evaluation Saco River Saco & Biddeford, Maine FEDERAL NAVIGATION PROJECT MAINTENANCE DREDGING March 2016 New England District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers 696 Virginia Rd Concord, Massachusetts 01742-2751 Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 1 2.0 PROJECT HISTORY, NEED, AND AUTHORITY .......................................... 1 3.0 PROPOSED PROJECT DESCRIPTION ....................................................... 3 4.0 ALTERNATIVES ............................................................................................ 6 4.1 No Action Alternative ..................................................................................... 6 4.2 Maintaining Channel at Authorized Dimensions............................................. 6 4.3 Alternative Dredging Methods ........................................................................ 6 4.3.1 Hydraulic Cutterhead Dredge....................................................................... 7 4.3.2 Hopper Dredge ........................................................................................... 7 4.3.3 Mechanical Dredge .................................................................................... -

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

New Hampshire River Protection and Energy Development Project Final

..... ~ • ••. "'-" .... - , ... =-· : ·: .• .,,./.. ,.• •.... · .. ~=·: ·~ ·:·r:. · · :_ J · :- .. · .... - • N:·E·. ·w··. .· H: ·AM·.-·. "p• . ·s;. ~:H·1· ··RE.;·.· . ·,;<::)::_) •, ·~•.'.'."'~._;...... · ..., ' ...· . , ·....... ' · .. , -. ' .., .- .. ·.~ ···•: ':.,.." ·~,.· 1:·:,//:,:: ,::, ·: :;,:. .:. /~-':. ·,_. •-': }·; >: .. :. ' ::,· ;(:·:· '5: ,:: ·>"·.:'. :- .·.. :.. ·.·.···.•. '.1.. ·.•·.·. ·.··.:.:._.._ ·..:· _, .... · -RIVER~-PR.OT-E,CT.10-N--AND . ·,,:·_.. ·•.,·• -~-.-.. :. ·. .. :: :·: .. _.. .· ·<··~-,: :-:··•:;·: ::··· ._ _;· , . ·ENER(3Y~EVELOP~.ENT.PROJ~~T. 1 .. .. .. .. i 1·· . ·. _:_. ~- FINAL REPORT··. .. : .. \j . :.> ·;' .'·' ··.·.· ·/··,. /-. '.'_\:: ..:· ..:"i•;. ·.. :-·: :···0:. ·;, - ·:··•,. ·/\·· :" ::;:·.-:'. J .. ;, . · · .. · · . ·: . Prepared by ~ . · . .-~- '·· )/i<·.(:'. '.·}, •.. --··.<. :{ .--. :o_:··.:"' .\.• .-:;: ,· :;:· ·_.:; ·< ·.<. (i'·. ;.: \ i:) ·::' .::··::i.:•.>\ I ··· ·. ··: · ..:_ · · New England ·Rtvers Center · ·. ··· r "., .f.·. ~ ..... .. ' . ~ "' .. ,:·1· ,; : ._.i ..... ... ; . .. ~- .. ·· .. -,• ~- • . .. r·· . , . : . L L 'I L t. ': ... r ........ ·.· . ---- - ,, ·· ·.·NE New England Rivers Center · !RC 3Jo,Shet ·Boston.Massachusetts 02108 - 117. 742-4134 NEW HAMPSHIRE RIVER PRO'l'ECTION J\ND ENERGY !)EVELOPMENT PBOJECT . -· . .. .. .. .. ., ,· . ' ··- .. ... : . •• ••• \ ·* ... ' ,· FINAL. REPORT February 22, 1983 New·England.Rivers Center Staff: 'l'bomas B. Arnold Drew o·. Parkin f . ..... - - . • I -1- . TABLE OF CONTENTS. ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEMBERS . ~ . • • . .. • .ii EXECUTIVE -

Saco River and Camp Ellis Beach Saco, Maine

Shore Damage Mitigation Project Final Decision Document & Final Environmental Assessment Including Finding of No Significant Impact and Section 404(b)(1) Evaluation Saco River and Camp Ellis Beach Saco, Maine Beachfill Stone Spur Jetty Saco River DRAFT September 2017 This Page Intentionally Left Blank Back of Front Cover DRAFT SACO RIVER AND CAMP ELLIS BEACH SACO, MAINE SECTION 111 SHORE DAMAGE MITIGATION PROJECT FINAL DECISION DOCUMENT DRAFT SEPTEMBER 2017 This Page Intentionally Left Blank DRAFT SACO RIVER AND CAMP ELLIS BEACH SHORE DAMAGE MITIGATION PROJECT SACO, MAINE DECISION DOCUMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Study Authority 1 1.2 Purpose and Scope 4 1.3 Study Area 4 1.4 Existing Federal Navigation Project 4 1.4.1 Construction History of the Navigation Project 6 1.4.2 Navigation Uses of the Federal Project 6 1.5 Feasibility Study Process 7 1.6 Environmental Operating Principles 8 1.7 USACE Campaign Plan 9 2.0 PLANNING SETTING AND PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION 10 2.1 General Setting 10 2.2 Topography and Geology 10 2.2.1 Physiography 10 2.2.2 Marine Geology and Geophysics 10 2.3 Soils and Sediments 11 2.3.1 Onshore (Upland) Soils 11 2.3.2 Marine Sediments 12 2.4 Water Resources 12 2.4.1 Saco River 12 2.4.2 Coastal Processes (Erosion History and Coastal Modeling) 13 2.4.3 Marine Water Quality 15 2.5 Biological Resources 15 2.5.1 General 15 2.5.2 Eelgrass DRAFT 15 2.5.3 Benthic Resources 16 2.5.4 Shellfish 16 2.5.5 Fisheries Resources 17 2.5.6 Essential Fish Habitat 18 2.6 Wildlife Resources 18 2.6.1 General Wildlife Species -

Surface Water Supply of the United States 1915 Part I

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRANKLIN K. LANE, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 401 SURFACE WATER SUPPLY OF THE UNITED STATES 1915 PART I. NORTH ATLANTIC SIOPE DRAINAGE BASINS NATHAN C. GROVES, Chief Hydraulic Engineer C. H. PIERCE, C. C. COVERT, and G. C. STEVENS. District Engineers Prepared in cooperation with the States of MAIXE, VERMONT, MASSACHUSETTS, and NEW YORK WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT FEINTING OFFICE 1917 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRANKLIN K. LANE, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Water-Supply Paper 401 SURFACE WATER SUPPLY OF THE UNITED STATES 1915 PART I. NORTH ATLANTIC SLOPE DRAINAGE BASINS NATHAN C. GROVER, Chief Hydraulic Engineer C. H. PIERCE, C. C. COVERT; and G. C. STEVENS, District Engineers Geological Prepared in cooperation with the States MAINE, VERMONT, MASSACHUSETTS^! N«\f Yd] WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1917 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE PROCURED FROM THE SUPEBINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT FEINTING OFFICE "WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 15 CENTS PER COPY V CONTENTS. Authorization and scope of work........................................... 7 Definition of terms....................................................... 8 Convenient equivalents.................................................... 9 Explanation of data...................................................... 11 Accuracy of field data and computed results................................ 12 Cooperation.............................................................. -

Wetlands Characterization B R Eliza Beth.Hertz@M a Ine.Gov)

T N A R G S M R A E H D E L N E O H T C S k o T o A r k o B B An Approach to Conserving Maine's Natural o r LEGEND e Space for Plants, Animals, and People B k a n w s e T his m a p depicts a ll wetla nds shown on Na tiona l W etla nd Inventory (NW I) m a ps, but l o t t www..begiinniingwiitthhabiittatt..org d ca tegorized them ba sed on a subset of wetla nd functions. T his m a p a nd its depiction a a R e of wetla nd fea tures neither substitute for nor elim ina te the need to perform on-the- M Virginia ground wetla nd delinea tion a nd functiona l a ssessm ent. In no wa y sha ll use of this m a p Supplementary Map 7 G Lake r dim inish or a lter the regula tory protection tha t a ll wetla nds a re a ccorded under e a t a pplica ble S ta te a nd Federa l la ws. For m ore inform a tion a bout wetla nds cha ra cteriza tion, conta ct Eliza beth H ertz a t the Ma ine Depa rtm ent of Conserva tion (207-287-8061, Wetlands Characterization B r eliza beth.hertz@m a ine.gov). o o Lov ell k k o Keewaydin This map is non-regulatory and is intended for planning purposes only o T he W etla nds Cha ra cteriza tion m odel is a pla nning tool intended to help identify likely r Lake B wetla nd functions a ssocia ted with significa nt wetla nd resources a nd a dja cent upla nds. -

Index of Surface-Water Records

~EOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 138 July 1951 INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER RECORDS PART I.-NORTH ATLANTIC SLOPE BASINS TO SEPTEMBER 30, 1950 Prepared by Boston District UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director Washington, 'J. C. Free on application to the Geological Survey, Washington 26, D. C. INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER RECORDS PART 1.-NORTH ATLANTIC SLOPE BASINS TO SEPTEMBER 30, 1950 EXPLANATION The index lists the stream-flow and reservoir stations in the North Atlantic Slope Basins for which records have been or are to be published for periods prior to Sept. 30, 1950. The stations are listed in downstream order. Tributary streams are indicated by indention. Station names are given in their most recently published forms. Parentheses around part of a station name indicate that the inclosed word or words were used in an earlier published name of the station or in a name under which records were published by some agency other than the Geological Survey. The drainage areas, in square miles, are the latest figures pu~lished or otherwise available at this time. Drainage areas that were obviously inconsistent with other drainage areas on the same stream have been omitted. Under "period of record" breaks of less than a 12-month period are not shown. A dash not followed immediately by a closing date shows that the station was in operation on September 30, 1950. The years given are calendar years. Periods·of records published by agencies other than the Geological Survey are listed in parentheses only when they contain more detailed information or are for periods not reported in publications of the Geological Survey. -

Survival and Movement of Fall-Stocked Brown Trout in the Lower Saco River

Fishery Final Report Series No. 16-2 Survival and Movement of Fall-Stocked Brown Trout in the Lower Saco River By: Francis C. Brautigam Sebago Region December 2016 Maine Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife Fisheries and Hatcheries Division Job F-012 Survival and Movement of Fall-Stocked Brown Trout in the Lower Saco River Final Report No. 16-2 SUMMARY A telemetry study was conducted to assess the survival and movement of hatchery brown trout stocked in the lower 13.1 mile portion of the Saco River. For more than 10 years this river reach has been managed under special fishing regulations to allow year-round fishing and recreational harvest. Most Maine rivers and streams are open to recreational fishing from April through September. Fifty-nine fall yearling hatchery brown trout were equipped with radio transmitters and stocked below Skelton Dam (Town of Dayton) in the fall of 2013. All stocked fish were of a size that could be legally harvested by anglers. The movement and survival of these fish were monitored from October 2013 through August of 2014 using a portable and stationary receiver. Transmission signals indicated 64% of the study fish were alive within the 13.1 mile long study reach two months after stocking. By May of 2014 transmission signals were detected from 25% of the study fish, and by August (2014) signals were detected from 3% of the study fish. Transmitters were equipped with mortality switches, which were permanently activated in 44% of the fish over the course of the study. Monthly mortality was low throughout the study, with the heaviest mortality observed between March and May. -

Report of the Board of Metropolitan Park Commissioners (1898)

A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/reportofboardofm00mass_4 PUBLIC DOCUMENT No. 48. REPORT ~ Board of Metropolitan Park Commissioners. J^ANUARY, 1899. BOSTON : W RIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 Post Office Square. 1899. A CONTENTS. PAGE Report of the Commissioners, 5 Report of the Secretary, 18 Report of the Landscape Architects, 47 Report of the Engineer, 64 Financial Statement, . 86 Analysis of Payments, 99 Claims (chapter 366 of the Acts of 1898), 118 KEPOKT. The Metropolitan Park Commission presents herewith its sixth annual report. At the presentation of its last report the Board was preparing to continue the acquirement of the banks of Charles River, and was engaged in the investigation of avail- able shore frontages and of certain proposed boulevards. Towards the close of its last session the Legislature made an appropriation of $1,000,000 as an addition to the Metropolitan Parks Loan, but further takings were de- layed until the uncertainties of war were clearly passed. Acquirements of land and restrictions have been made or provided for however along Charles River as far as Hemlock Gorge, so that the banks for 19 miles, except where occu- pied by great manufacturing concerns, are in the control either of this Board or of some other public or quasi public body. A noble gift of about 700 acres of woods and beau- tiful intervales south of Blue Hills and almost surroundingr Ponkapog Pond has been accepted under the will of the late ' Henry L. Pierce. A field in Cambridge at the rear of « Elm- wood," bought as a memorial to James Russell Lowell, has been transferred to the care of this Board, one-third of the purchase price having been paid by the Commonwealth and the remaining two-thirds by popular subscription, and will be available if desired as part of a parkway from Charles River to Fresh Pond. -

What Is a “Fish Ladder”? by the Numbers

What is a “fish ladder”? By the numbers... A manmade structure There are 13 diadromous species in Massachusetts, (which often resembles including river herring, American eels, and rainbow smelt! a ladder with steps) that allows fish swimming upstream DMF designs and installs eel ramps in coastal rivers to Rainbow Smelt to get past barriers like dams, Smelt spawn at night in freshwater assist their upstream migrations. 9 have been installed in from early March through May. waterfalls, and locks. Massachusetts since 2007! Female rainbow smelt can lay VIEWING GUIDE Baffle fishways look just Weir pools are between 5,000 and 80,000 eggs! like ladders! Examples made up of a There are over 100 separate river herring runs in Each spring, MILLIONS of river herring migrate into Massachusetts waters, returning include Denil and Alaskan series of small pools Massachusetts! to their place of birth to create a new generation! This guide offers information on Steeppass. of regular length to create a long, sloping fifteen of our state’s busiest fish passage locations. channel for fish to travel upstream. Since 2013, 23,500 river herring have been stocked throughout the region by DMF! Life Cycle of a Herring River Herring swim very fast in short bursts to pass up the ladder, making for a spectacular show! diadromous, adj. [dahy·ad·ruh·muh s] American Eel Egg laying (spawning) 1. (of fish) migrating between fresh The only catadromous fish in North happens in the same Woolen Mill Dam and Fishway America, meaning it lives mostly in April 15 - May 15 and salt waters. -

Maine Legacy Spring 2001 First Impressions: Ross Geredien Is a Conservancy Intensifying Our Activities Here

library Use Only Temcv M a in e * * I Spring 2001 TheNature Conservancy Migrations Merrymeeting Bay/ tel of ice, the geese leapfrog north in a River. When Neil found that the Con cycle alternating between rest and servancy was interested in conserving Lower Kennebec Estuary flight. Critical on their migration route his land, he dropped all other offers, White as the blocks of ice below, are areas where they can bulk up on including a proposal to develop a new the geese called back and forth, their foods that provide the necessary calo airstrip, and began exploring conser voices high-pitched and nasal. The ice, ries to complete the next stage of their vation options. breaking from the shoreline, joined a journey. Snow geese, while very com Because a portion of the land was frozen flotilla drifting with the river’s mon in some areas, are still a rare sight in the estate of Derril O. Lamb, current, flowing to the ocean. ing along Maine’s coast. founder of Marriner Lumber, selling Although this flock of snow geese the property was necessary for the fam his flock of Snow geese had could not know it, the Conservancy has ily, but having the property cleared and T come a long way on its spring spent the better part of the winter mak developed was not. As a tribute to migration, and still had a long way to ing sure they and many other species Derril Lamb, the estate and Marriner go. As they had cleared Casco Bay, the will enjoy a safe migration. -

Introduction

Mousam River near Sanford, Maine The majority of sampling effort in the Salmon Falls basin has focused on stations on the mainstem affected by dams and wastewater discharges. The Salmon Falls River has been managed as Class B for many years but has experienced continual problems attaining Class B standards for dissolved oxygen, bacteria and aquatic life, in the lower reaches,. All aquatic life monitoring stations downstream of the Berwick sewage treatment plant fail to attain assigned Class B standards. Introduction Geography The Saco River basin covers 1,696 square miles. The River originates at Saco Lake just north of Crawford Notch, New Hampshire and flows through the Mt. Washington Valley. About half of the drainage area is in the State of New Hampshire. Just east of Conway, New Hampshire it crosses into Maine, near Fryeburg, winds northeast for a short distance, and then meanders south- southeast through the mountains and hills of Western Maine. The Saco River continues southeast towards the urban coastal areas of Biddeford and Saco before emptying into Saco Bay. The total length from the Maine/New Hampshire border is approximately 85 miles. There are four other sampled streams in the Saco River basin listed in Basin Table 9. The Piscataqua/Salmon Falls River basin covers 1,356 sq. miles. The Piscataqua River is the tidal portion of the Salmon Falls River. The Biological Monitoring Program has not conducted any sampling in the tidal portions of the river so the remainder of this report will focus on the Salmon Falls River. For its entire length, including below head of tide, the River forms the Maine/New Hampshire border.