The Pathos, Truths and Narratives of Thermopylae in 300

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Thyrea, Thermopylae and Narrative Patterns in Herodotus Author(S): John Dillery Source: the American Journal of Philology, Vol

Reconfiguring the Past: Thyrea, Thermopylae and Narrative Patterns in Herodotus Author(s): John Dillery Source: The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 117, No. 2 (Summer, 1996), pp. 217-254 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1561895 Accessed: 06/09/2010 12:38 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=jhup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Journal of Philology. -

Download Press Notes

Strand Releasing presents LION’S DEN A film by PABLO TRAPERO Official Competition, Cannes Film Festival 2008 Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival 2008 Country of Origin: Argentina/In Spanish with English Subtitles Shooting format: Super 35mm / Color Aspect Ratio: 2:35 Sound: Dolby SRD Running Time: 113 minutes LA/National Publicity: Michael Berlin / Marcus Hu Strand Releasing phone: (310) 836-7500 fax: (310) 836-7500 [email protected] [email protected] Please download photos from our website: http://extranet.strandreleasing.com/login.aspx Synopsis Julia wakes up in her apartment, surrounded by the bloody corpses of Ramiro and Nahuel. Ramiro is still alive; Nahuel is dead. Both have been, obscure and simultaneously, her lovers and one made Julia pregnant. Julia is sent to a prison housing mothers and pregnant inmates. There she spends her first days absorbed and aloof. Two characters enter her life. One is Marta, a fellow inmate who has reared two children in prison and who becomes her guide and counselor; the other is Sofía, Julia’s own mother, an ambiguous character who Julia meets up with again after many years. Sofía attempts to repair the mistakes of the past; she helps her daughter, gets her a good lawyer, sends her baby clothes, and slowly reestablishes her relationship with Julia. The legal case involving the death of Nahuel, has two possible guilty parties: Julia and Ramiro, both in prison in different penitentiaries. Their testimonies are contradictory, one incriminating the other. The child is born, a baby boy whose name is Tomás. Bringing up a child in prison is difficult. -

Showcase LION’S LAST STAND Leonidas, Which Is Greek for “Lion’S Son” Or “Lion-Like,” Was Born Around 540 B.C., the Son of T Y King Anaxandrides II

could be of a delicate nature, the Persian threat to their freedom led many Greeks to unite SC together in an alliance. TH AL While the Persians’ superior numbers /6 E eventually overran the Greeks, the defenders’ 1 sacrifice has never been forgotten. Monuments to both the Spartans and the Thespians can be found at Thermopylae today. The last stand at Thermopylae has also captured the popular imagination thanks to books like Steven Pressfield’s fictional “Gates of Fire.” Movies include 1962’s “The 300 Spartans,” starring Richard Egan as Leonidas; and 2006’s “300,” with Gerard Butler portraying the Greek commander. SHOWCASE LION’S LAST STAND Leonidas, which is Greek for “Lion’s son” or “Lion-like,” was born around 540 B.C., the son of T Y King Anaxandrides II. At this time Sparta had two H kings who shared in ruling the state. One leader would be a descendant of the Agiad dynasty, as E M was Leonidas, while the other would be a S R descendant of Eurypon in this twin monarchy. IXTH A Leonidas was married to Gorgo, the daughter of his half-brother King Cleomenes I. At some point between 490 and 488 B.C., Leonidas became King after his half-brother went mad and committed suicide. Scott J. Dummitt and Bill Thomas Leonidas faced a difficult decision as the Persian invasion of Greece developed. Spartan cover the latest action figure- law forbade him from leading the army out of the kingdom during a religious festival being held at the time. However, it would be unthinkable to not related items. -

Herodotus, Xerxes and the Persian Wars IAN PLANT, DEPARTMENT of ANCIENT HISTORY

Herodotus, Xerxes and the Persian Wars IAN PLANT, DEPARTMENT OF ANCIENT HISTORY Xerxes: Xerxes’ tomb at Naqsh-i-Rustam Herodotus: 2nd century AD: found in Egypt. A Roman copy of a Greek original from the first half of the 4th century BC. Met. Museum New York 91.8 History looking at the evidence • Our understanding of the past filtered through our present • What happened? • Why did it happen? • How can we know? • Key focus is on information • Critical collection of information (what is relevant?) • Critical evaluation of information (what is reliable?) • Critical questioning of information (what questions need to be asked?) • These are essential transferable skills in the Information Age • Let’s look at some examples from Herodotus’ history of the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC • Is the evidence from: ― Primary sources: original sources; close to origin of information. ― Secondary sources: sources which cite, comment on or build upon primary sources. ― Tertiary source: cites only secondary sources; does not look at primary sources. • Is it the evidence : ― Reliable; relevant ― Have I analysed it critically? Herodotus: the problem… Succession of Xerxes 7.3 While Darius delayed making his decision [about his successor], it chanced that at this time Demaratus son of Ariston had come up to Susa, in voluntary exile from Lacedaemonia after he had lost the kingship of Sparta. [2] Learning of the contention between the sons of Darius, this man, as the story goes, came and advised Xerxes to add this to what he said: that he had been born when Darius was already king and ruler of Persia, but Artobazanes when Darius was yet a subject; [3] therefore it was neither reasonable nor just that anyone should have the royal privilege before him. -

Everybody Loves a Muscle Boi”: Homos, Heroes, and Foes in Post-9/11 Spoofs of the 300 Spartans

1 “Everybody Loves a Muscle Boi”: Homos, Heroes, and Foes in Post-9/11 Spoofs of the 300 Spartans Ralph J. Poole “It’s Greek to whom?” In 2007-2008, a significant accumulation of cinematic and other visual media took up a celebrated episode of Greek antiquity recounting in different genres and styles the rise of the Spartans against the Persians. Amongst them are the documentary The Last Stand of the 300 (2007, David Padrusch), the film 300 (2007, Zack Snyder), the video game 300: March to Glory (2007, Collision Studios), the short film United 300 (2007, Andy Signore), and the comedy Meet the Spartans (2008, Jason Friedberg/Aaron Seltzer). Why is the legend of the 300 Spartans so attractive for contemporary American cinema? A possible, if surprising account for the interest in this ancient theme stems from an economic perspective. Written at the dawn of the worldwide financial crisis, the fight of the 300 Spartans has served as point of reference for the serious loss of confidence in the banking system, but also in national politics in general. William Streeter of the ABA Banking Journal succinctly wonders about what robs bankers’ precious resting hours: What a fragile thing confidence is. Events of the past six months have seen it coalesce and evaporate several times. […] This is what keeps central bankers awake at night. But then that is their primary reason for being, because the workings of economies and, indeed, governments, hinge upon trust and confidence. […] With any group, whether it be 300 Spartans holding off a million Persians at Thermopylae or a group of central bankers trying to keep a global financial community from bolting, trust is a matter of individual decisions. -

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

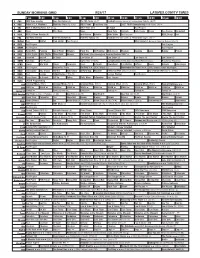

Sunday Morning Grid 9/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Presidents Cup 2017 TOUR Championship Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Outback Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program MLS Soccer LA Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons DW News: Live Coverage of German Election 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana The Reef ›› (2006, Niños) (G) Remember the Titans ››› (2000, Drama) Denzel Washington. -

Ebook Download Greek Art 1St Edition

GREEK ART 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nigel Spivey | 9780714833682 | | | | | Greek Art 1st edition PDF Book No Date pp. Fresco of an ancient Macedonian soldier thorakitai wearing chainmail armor and bearing a thureos shield, 3rd century BC. This work is a splendid survey of all the significant artistic monuments of the Greek world that have come down to us. They sometimes had a second story, but very rarely basements. Inscription to ffep, else clean and bright, inside and out. The Erechtheum , next to the Parthenon, however, is Ionic. Well into the 19th century, the classical tradition derived from Greece dominated the art of the western world. The Moschophoros or calf-bearer, c. Red-figure vases slowly replaced the black-figure style. Some of the best surviving Hellenistic buildings, such as the Library of Celsus , can be seen in Turkey , at cities such as Ephesus and Pergamum. The Distaff Side: Representing…. Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. The Greeks were quick to challenge Publishers, New York He and other potters around his time began to introduce very stylised silhouette figures of humans and animals, especially horses. Add to Basket Used Hardcover Condition: g to vg. The paint was frequently limited to parts depicting clothing, hair, and so on, with the skin left in the natural color of the stone or bronze, but it could also cover sculptures in their totality; female skin in marble tended to be uncoloured, while male skin might be a light brown. After about BC, figures, such as these, both male and female, wore the so-called archaic smile. -

The Phocian Betrayal at Thermopylae

historia 68, 2019/4, 413–435 DOI 10.25162/historia-2019-0022 Jeffrey Rop The Phocian Betrayal at Thermopylae Abstract: This article makes three arguments regarding the Battle of Thermopylae. First, that the discovery of the Anopaea path was not dependent upon Ephialtes, but that the Persians were aware of it at their arrival and planned their attacks at Thermopylae, Artemisium, and against the Phocians accordingly. Second, that Herodotus’ claims that the failure of the Pho- cians was due to surprise, confusion, and incompetence are not convincing. And third, that the best explanation for the Phocian behavior is that they were from Delphi and betrayed their allies as part of a bid to restore local control over the sanctuary. Keywords: Thermopylae – Artemisium – Delphi – Phocis – Medism – Anopaea The courageous sacrifice of Leonidas and the Spartans is perhaps the central theme of Herodotus’ narrative and of many popular retellings of the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE. Even as modern historians are appropriately more critical of this heroizing impulse, they have tended to focus their attention on issues that might explain why Leo- nidas and his men fought to the death. These include discussion of the broader strategic and tactical importance of Thermopylae, the inter-relationship and chronology of the Greek defense of the pass and the naval campaign at Artemisium, the actual number of Greeks who served under Leonidas and whether it was sufficient to hold the position, and so on. While this article inevitably touches upon some of these same topics, its main purpose is to reconsider the decisive yet often overlooked moment of the battle: the failure of the 1,000 Phocians on the Anopaea path. -

January 13, 2009 (XVIII:1) Carl Theodor Dreyer VAMPYR—DER TRAUM DES ALLAN GREY (1932, 75 Min)

January 13, 2009 (XVIII:1) Carl Theodor Dreyer VAMPYR—DER TRAUM DES ALLAN GREY (1932, 75 min) Directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer Produced by Carl Theodor Dreyer and Julian West Cinematography by Rudolph Maté and Louis Née Original music by Wolfgang Zeller Film editing by Tonka Taldy Art direction by Hermann Warm Special effects by Henri Armand Allan Grey…Julian West Der Schlossherr (Lord of the Manor)…Maurice Schutz Gisèle…Rena Mandel Léone…Sybille Schmitz Village Doctor…Jan Heironimko The Woman from the Cemetery…Henriette Gérard Old Servant…Albert Bras Foreign Correspondent (1940). Some of the other films he shot His Wife….N. Barbanini were The Lady from Shanghai (1947), It Had to Be You (1947), Down to Earth (1947), Gilda (1946), They Got Me Covered CARL THEODOR DREYER (February 3, 1889, Copenhagen, (1943), To Be or Not to Be (1942), It Started with Eve (1941), Denmark—March 20, 1968, Copenhagen, Denmark) has 23 Love Affair (1939), The Adventures of Marco Polo (1938), Stella Directing credits, among them Gertrud (1964), Ordet/The Word Dallas (1937), Come and Get It (1936), Dodsworth (1936), A (1955), Et Slot i et slot/The Castle Within the Castle (1955), Message to Garcia (1936), Charlie Chan's Secret (1936), Storstrømsbroen/The Storstrom Bridge (1950), Thorvaldsen Metropolitan (1935), Dressed to Thrill (1935), Dante's Inferno (1949), De nåede færgen/They Caught the Ferry (1948), (1935), Le Dernier milliardaire/The Last Billionaire/The Last Landsbykirken/The Danish Church (1947), Kampen mod Millionaire (1934), Liliom (1934), Paprika (1933),