Transportation Whitepaper SAWC 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sitka Area Fishing Guide

THE SITKA AREA ................................................................................................................................................................... 3 ROADSIDE FISHING .............................................................................................................................................................. 4 ROADSIDE FISHING IN FRESH WATERS .................................................................................................................................... 4 Blue Lake ........................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Beaver Lake ....................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Sawmill Creek .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Thimbleberry and Heart Lakes .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Indian River ....................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Swan Lake ......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Sea Kayaking on the Petersburg

SeaSea KayakingKayaking onon thethe PetersburgPetersburg RangerRanger DistrictDistrict Routes Included in Handout Petersburg to Kake via north shore of Kupreanof Island Petersburg to Kake via south shore of Kupreanof Island LeConte Bay Loop Thomas Bay Loop Northwest Kuiu Island Loop Duncan Canal Loop Leave No Trace (LNT) information Tongass National Forest Petersburg Ranger District P.O. Box 1328 Petersburg AK. 99833 Sea Kayaking in the Petersburg Area The Petersburg area offers outstanding paddling opportunities. From an iceberg filled fjord in LeConte Bay to the Keku Islands this remote area has hundreds of miles of shoreline to explore. But Alaska is not a forgiving place, being remote, having cold water, large tides and rug- ged terrain means help is not just around the corner. One needs to be experienced in both paddling and wilderness camping. There are not established campsites and we are trying to keep them from forming. To help ensure these wild areas retain their naturalness it’s best to camp on the durable surfaces of the beach and not damage the fragile uplands vegetation. This booklet will begin to help you plan an enjoyable and safe pad- dling tour. The first part contains information on what paddlers should expect in this area and some safety guidelines. The second part will help in planning a tour. The principles of Leave No Trace Camping are presented. These are suggestions on how a person can enjoy an area without damaging it and leave it pristine for years to come. Listed are over 30 Leave No Trace campsites and several possible paddling routes in this area. -

Climate Change in Alaska

CLIMATE CHANGE ANTICIPATED EFFECTS ON ECOSYSTEM SERVICES AND POTENTIAL ACTIONS BY THE ALASKA REGION, U.S. FOREST SERVICE Climate Change Assessment for Alaska Region 2010 This report should be referenced as: Haufler, J.B., C.A. Mehl, and S. Yeats. 2010. Climate change: anticipated effects on ecosystem services and potential actions by the Alaska Region, U.S. Forest Service. Ecosystem Management Research Institute, Seeley Lake, Montana, USA. Cover photos credit: Scott Yeats i Climate Change Assessment for Alaska Region 2010 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 Regional Overview- Alaska Region ..................................................................................................... 2 3.0 Ecosystem Services of the Southcentral and Southeast Landscapes ................................................. 5 4.0 Climate Change Threats to Ecosystem Services in Southern Coastal Alaska ..................................... 6 . Observed changes in Alaska’s climate ................................................................................................ 6 . Predicted changes in Alaska climate .................................................................................................. 7 5.0 Impacts of Climate Change on Ecosystem Services ............................................................................ 9 . Changing sea levels ............................................................................................................................ -

Forest Health Conditions in Alaska 2020

Forest Service U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Alaska Region | R10-PR-046 | April 2021 Forest Health Conditions in Alaska - 2020 A Forest Health Protection Report U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, State & Private Forestry, Alaska Region Karl Dalla Rosa, Acting Director for State & Private Forestry, 1220 SW Third Avenue, Portland, OR 97204, [email protected] Michael Shephard, Deputy Director State & Private Forestry, 161 East 1st Avenue, Door 8, Anchorage, AK 99501, [email protected] Jason Anderson, Acting Deputy Director State & Private Forestry, 161 East 1st Avenue, Door 8, Anchorage, AK 99501, [email protected] Alaska Forest Health Specialists Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, http://www.fs.fed.us/r10/spf/fhp/ Anchorage, Southcentral Field Office 161 East 1st Avenue, Door 8, Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: (907) 743-9451 Fax: (907) 743-9479 Betty Charnon, Invasive Plants, FHM, Pesticides, [email protected]; Jessie Moan, Entomologist, [email protected]; Steve Swenson, Biological Science Technician, [email protected] Fairbanks, Interior Field Office 3700 Airport Way, Fairbanks, AK 99709 Phone: (907) 451-2799, Fax: (907) 451-2690 Sydney Brannoch, Entomologist, [email protected]; Garret Dubois, Biological Science Technician, [email protected]; Lori Winton, Plant Pathologist, [email protected] Juneau, Southeast Field Office 11175 Auke Lake Way, Juneau, AK 99801 Phone: (907) 586-8811; Fax: (907) 586-7848 Isaac Dell, Biological Scientist, [email protected]; Elizabeth Graham, Entomologist, [email protected]; Karen Hutten, Aerial Survey Program Manager, [email protected]; Robin Mulvey, Plant Pathologist, [email protected] State of Alaska, Department of Natural Resources Division of Forestry 550 W 7th Avenue, Suite 1450, Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: (907) 269-8460; Fax: (907) 269-8931 Jason Moan, Forest Health Program Coordinator, [email protected]; Martin Schoofs, Forest Health Forester, [email protected] University of Alaska Fairbanks Cooperative Extension Service 219 E. -

NORTHERN TRANSMISSION LINE of the SOUTHEAST INTERTIE and DOCK ELECTRIFICATION for NORTHERN LYNN CANAL COMMUNITIES-SKAGWAY, HAINES, JUNEAU

NORTHERN TRANSMISSION LINE OF THE SOUTHEAST INTERTIE and DOCK ELECTRIFICATION FOR NORTHERN LYNN CANAL COMMUNITIES-SKAGWAY, HAINES, JUNEAU Description. The Northern Transmission Line (NTL). A high voltage 138 kV and 69 kV transmission line that interconnects Skagway, Haines, and Juneau for Energy Security, Energy Reliability, and Resilience to support sustainable economies of Northern Southeast Alaska. Purpose and Need. The Purpose of the NTL is to create an integrated transmission grid for northern Lynn Canal communities to transfer locally developed electricity between the communities to optimize renewable energy resources, drive down energy costs, open economic opportunities and to create value to the interconnected communities and their industries. Time is Now. Background. Envisioned in 1997, and passed into Public Law in 2000 to create a Southeast Intertie from Ketchikan to Skagway. PL 105-511 authorized $384M for a 25-year plan for interconnecting existing and planned power generation sites with a high voltage electrical intertie serving the communities of the region. The time is now to build the next phase of the SE Intertie to serve northern Lynn Canal communities. The NTL is a fully permitted and construction-ready high voltage transmission line infrastructure to span Skagway, Haines, and Juneau with substations and overhead and submarine transmission segments to serve these communities for the next century. Benefits. • Creates family-wage jobs now to supplement the Alaska economy circulating federal and private infrastructure dollars by building keystone energy infrastructure. • Upgrades and replaces impaired Skagway to Haines undersea transmission cable. • Future proof the Northern Lynn Canal economies and opens up more trade opportunities between communities and with Yukon. -

Sitka Community Resource Guide

COMMUNITY RESOURCE GUIDE SITKA, ALASKA 2019 First Created By Sitka Legislative Information Office Legislative Affairs Agency 201 Katlian Street, Suite 103 Updated by The Advocates for Elders Services Group Sitka, AK 99835 907-966-4250 This Community Resource Guide was updated as of August 2019 as an effort by the The Advocates for Elders Service Group to connect our community with other Sitka organizations that may not be easily found in the local phone directory. This is considered a living document and we expect changes will occur. We apologize in advance for any errors. For updates or edits, please email: [email protected] The Advocates for Elders Service Group would like to acknowledge its members and all others involved with the update of this resource guide. Table of Contents Emergency……………………………………………………………….. 1 Child Care...........................................................................................2 Faith-based Organizations..................................................................3 Education ..........................................................................................5 Colleges and Universities....................................................................7 Libraries...............................................................................................8 Elected Officials ………………………………………………………….. 8 Fraternal and Professional organizations ……………………………....9 Handyman/Contractor Services ………………………………………..13 Health and Human Services. ............................................................13 -

Managing Alaska's Wildlife

Managing Alaska’s Wildlife 2010 Report Division of Wildlife Conservation Alaska Department of Fish & Game Director’s Message In my nearly 25 years working as a wildlife profes sional with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G), I have had the incredible opportunity and pleasure of working with a variety of species in man agement and research efforts. From Sitka black-tailed deer, mountain goats, river otters, and black bears in Southeast Alaska, to caribou, moose, wolves, sheep, and brown bears in Northwest Alaska, the encoun ters have been phenomenal and memorable. Doug Larsen, director of the Division of Today, as the director of the Division of Wildlife Con- Wildlife Conservation, with a sedated servation, I have the opportunity to see first-hand on mountain goat. Aerial darting is an a regular basis the diversity of responsibilities that important tool for wildlife biologists in face our staff as we seek to conserve and enhance the Alaska, and Larsen’s experience darting State’s wildlife and habitats and provide for a wide goats paid off in 2005 when DWC began range of public uses and benefits. an ongoing study monitoring mountain Management activities conducted by ADF&G include, goat populations and the goats’ seasonal movements in the coastal mountains among other things, surveying populations of moose, north of Juneau. caribou, sheep, goats, bears, and wolves; assessing habitat conditions; regulating harvests of predator and prey populations; providing information and education opportunities to the public; and responding to a host of issues and concerns. We’re extremely fortunate at the Alaska Depart ment of Fish and Game to have skilled, educated, experienced, and dedicated staff to enable us to fulfill our mission. -

Southeast Alaska 2020 Economic Plan Southeast Conference’S Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy 2016-2020

SOUTHEAST CONFERENCE Southeast Alaska 2020 Economic Plan Southeast Conference’s Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy 2016-2020 May 2016 Prepared by Rain Coast Data Southeast Alaska Economic Plan Page 4 SOUTHEAST CONFERENCE Southeast Alaska 2020 Economic Plan Introduction Southeast Conference is a designated Economic SWOT Analysis to identify regional Strengths, Development District (EDD) through the US Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats Economic Development Administration (EDA). As page 15; the region’s EDD, Southeast Conference is Economic Resilience map detailing how Southeast responsible for developing a Comprehensive Alaska communities intend to respond to the Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) for looming State fiscal crisis page 16; Southeast Alaska designed to identify regional priorities for economic and community Strategic Direction Action Plan incorporating development. This plan follows the new guidelines tactics identified through planning process, other released by the US Economic Development plans, and stakeholder feedback to develop the Administration in February 2015. The CEDS is a priority strategies for the region pages 17-29; strategy-driven plan developed by a diverse Strategic Direction Action Plan Part II Priority workgroup of local representatives from private, Objective Descriptions and Evaluation public, and nonprofit sectors. The following sections Framework to identify and monitor performance form the basis for the Southeast Conference CEDS: measures associated with the plan pages 30 to 39; One page Strategic Plan Summary page 2; Economic Plan Steering Committee roster of Summary Background of economic conditions in names page 40; the region pages 3-14; Appendices page 41. The CEDS process began in March 2015 to ensure maximum input from the Southeast Conference membership. -

Ketchikan Inventory October 1984 Unit, Alaska, 1974 Willem W.S

United States Department of Agriculture Timber Resource Forest Service Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Statistics for the Experiment Station Resource Bulletin PNW-117 Ketchikan Inventory October 1984 Unit, Alaska, 1974 Willem W.S. van Hees This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Text errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. WILLEM W. S. van HEES is a research forester for Alaska Forest Inventory and Analysis located at the Forestry Sciences Laboratory, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, 2221 E. Northern Lights Blvd., Anchorage, Alaska 99508. Abstract van Hees, Willem W. S. Timber resource statistics for the Ketchikan inventory unit, Alaska, 1974. Resour. Bull. PNW-117. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station; 1984. 33 p. Statistics on forest area, total gross and net timber volumes, and annual net growth and mortality are presented from the 1974 timber inventory of the Ketchikan. unit, Alaska. Timberland area is estimated at 1.16 million acres (470 040 ha), net growing stock volume at 6.39 billion cubic feet (181.04 million m3), and annual net growth and mortality at -33.12 million cubic feet and 55.56 million cubic feet (-0.94 and 1.57 million m3), respectively. Keywords: Forest surveys, timber resources, timber inventory resources (forest), statistics (forest), Alaska (southeast), southeast Alaska. Summary This report for the 3.304-million-acre (1.337-million-ha) Ketchikan timber inventory unit is the fifth in a series of six reports for southeast Alaska. The Ketchikan unit is at the southern end of the southeast Alaska panhandle and stretches from near Bradfield Canal at the northern end to Dixon Entrance and the Canadian border on the southern end. -

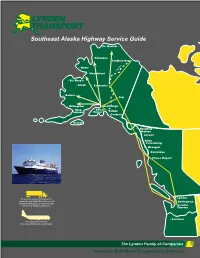

Southeast Alaska Highway Service Guide

Southeast Alaska Highway Service Guide Pt. Barrow • • Kotzebue Prudhoe Bay • • Nome Pipeline • Unalakleet • St. Mary’s • Aniak Fairbanks • • Bethel • Tok • Dillingham • Anchorage • Kenai • King • Valdez Salmon • Homer • Cordova • Kodiak • Skagway • Haines • Juneau • Sitka • Petersburg • Wrangell • Ketchikan • Prince Rupert • Lynden Three times weekly highway service connecting with Alaska State Ferries to all • Bellingham Southeast Alaska ports. Complete interport and Central Alaska Connections. • Seattle/ Tacoma • Portland Air cargo service beyond Anchorage/Fairbanks to rural Alaska. The Lynden Family of Companies Innovative Multi-Modal Transportation Solutions Central Alaska The fastest and most LTL specialist and small Anchorage: (907) 276-4800 frequent surface freight shipment experts. Cordova: (907) 424-7420 transportation to With our personalized service Lynden Fairbanks: (907) 456-5535 Transport can coordinate all your Glennallen: (907) 882-5565 Southeast Alaska! shipments quickly and efficiently. We Kenai: (907) 283-9640 With year-round speed, frequency, pride ourselves on providing special Kodiak: (907) 486-5354 dependability and control, Lynden care and handling of smaller, time Palmer/Wasilla: (907) 745-6683 Transport is more economical than air, sensitive shipments. Prudhoe Bay: (907) 659-2644 more frequent than barge, and on Tok: (907) 883-4851 smaller shipments, totally competitive. Southeast Alaska Ask about our minimum charge pro- gram. Service Features: Haines: (907) 766-2221 • Comprehensive cargo insurance Juneau: (907) 586-6600 • Computerized billing and expediting, Ketchikan: (907) 225-5550 electronic imaging, and Internet Petersburg: (907) 772-3278 Can’t wait for a barge or tracing Sitka: (907) 747-6625 just missed it? • Temperature control service for full Skagway: (907) 983-2281 With Lynden Transport and predictable truckloads Wrangell: (907) 874-3314 ferry schedules you know that Lynden’s • C.O.D. -

Mammals and Amphibians of Southeast Alaska

8 — Mammals and Amphibians of Southeast Alaska by S. O. MacDonald and Joseph A. Cook Special Publication Number 8 The Museum of Southwestern Biology University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico 2007 Haines, Fort Seward, and the Chilkat River on the Looking up the Taku River into British Columbia, 1929 northern mainland of Southeast Alaska, 1929 (courtesy (courtesy of the Alaska State Library, George A. Parks Collec- of the Alaska State Library, George A. Parks Collection, U.S. tion, U.S. Navy Alaska Aerial Survey Expedition, P240-135). Navy Alaska Aerial Survey Expedition, P240-107). ii Mammals and Amphibians of Southeast Alaska by S.O. MacDonald and Joseph A. Cook. © 2007 The Museum of Southwestern Biology, The University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Special Publication, Number 8 MAMMALS AND AMPHIBIANS OF SOUTHEAST ALASKA By: S.O. MacDonald and Joseph A. Cook. (Special Publication No. 8, The Museum of Southwestern Biology). ISBN 978-0-9794517-2-0 Citation: MacDonald, S.O. and J.A. Cook. 2007. Mammals and amphibians of Southeast Alaska. The Museum of Southwestern Biology, Special Publication 8:1-191. The Haida village at Old Kasaan, Prince of Wales Island Lituya Bay along the northern coast of Southeast Alaska (undated photograph courtesy of the Alaska State Library in 1916 (courtesy of the Alaska State Library Place File Place File Collection, Winter and Pond, Kasaan-04). Collection, T.M. Davis, LituyaBay-05). iii Dedicated to the Memory of Terry Wills (1943-2000) A life-long member of Southeast’s fauna and a compassionate friend to all. -

Lynden Transport Alaska Service Areas

Alaska Service Areas Multi-modal freight service to all points in Alaska (TL & LTL) Central Alaska Akhiok Clam Gulch English Bay Karluk Ninilchik Sterling Alitak Clear Ester Kasilof North Pole Summit Alpine Clear AFB Fairbanks Kenai Northway Sutton Alyeska Coldfoot Fort Greely Kodiak Old Harbor Talkeetna Anchor Point College Fort Richardson Kuparuk Ouzinkie Tanacross Anchorage Cooper Landing Fort Wainwright Larsen Bay Palmer Tatitlek Anderson Copper Center Fritz Creek Manley Hot Springs Paxson Tok Badami Cordova Gakona Matanuska Point Thompson Tolsona Badger Deadhorse Gakona Junction Mentasta Port Bailey Tonsina Big Delta Delta Junction Girdwood Miers Lake Port Graham Trapper Creek Big Lake Denali National Park Glennallen Milne Point Port Lions Tyonek Birchwood Donnelly Flats Gulkana Minto Port Williams Valdez Buffalo Center Dot Lake Gulkana Junction Moose Creek Portage Wasilla Cantwell Eagle Halibut Cove Moose Pass Prudhoe Bay West Operating Area Chenega Bay Eagle River Healy Moser Bay Pump Station 1 Whittier Chicken East Operating Area Homer Nanwalek Seldovia Willow Chiniak Eielson AFB Homer Spit Naptowne Seward Chitina Eklutna Hope Nenana Skwentna Chugiak Elmendorf AFB Houston Nikiski Slana Circle Endicott Indian Nikolaevsk Soldotna Southeast Alaska Angoon Elfin Cove Juneau Mendenhall Point Baker Thorne Bay Auke Bay Gustavus Kake Metlakatla Port Alexander Ward Cove Coffman Cove Haines Kasaan Meyers Chuck Saxman Wrangell Craig Hoonah Ketchikan Naukati Bay Sitka Yakutat Douglas Hydaburg Klawock Pelican Skagway Edna Bay Hyder Kupreanof