TCRP RRD No. 42-Technology and Joint Development of Cost-Effective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T and Analysis of Walkability in Hong Kong

Measurement and Analysis of Walkability in Hong Kong By: Michael Audi, Kathryn Byorkman, Alison Couture, Suzanne Najem ZRH006 Measurement and Analysis of Walkability in Hong Kong An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the faculty of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute In partial fulfillment of the requirements for Degree of Bachelor of Science In cooperation with Designing Kong Hong, Ltd. and The Harbour Business Forum On March 4, 2010 Submitted by: Submitted to: Michael Audi Paul Zimmerman Kathryn Byorkman Margaret Brooke Alison Couture Dr. Sujata Govada Suzanne Najem Roger Nissim Professor Robert Kinicki Professor Zhikun Hou ii | P a g e Abstract Though Hong Kong’s Victoria Harbour is world-renowned, the harbor front districts are far from walkable. The WPI team surveyed 16 waterfront districts, four in-depth, assessing their walkability using a tool created by the research team and conducted preference surveys to understand the perceptions of Hong Kong pedestrians. Because pedestrians value the shortest, safest, least-crowded, and easiest to navigate routes, this study found that confusing routes, unsafe or indirect connections, and a lack of amenities detract from the walkability in Hong Kong. This report provides new data concerning the walkability in harbor front districts and a tool to measure it, along with recommendations for potential improvements. iii | P a g e Acknowledgements Our team would like to thank the many people that helped us over the course of this project. First, we would like to thank our sponsors Paul Zimmerman, Dr. Sujata Govada, Margaret Brooke, and Roger Nissim for their help and dedication throughout our project and for providing all of the resources and contacts that we required. -

Initial Transport Assessment of Development Options

This subject paper is intended to be a research paper delving into different views and analyses from various sources. The views and analyses as contained in this paper are intended to stimulate public discussion and input to the planning process of the "HK2030 Study" and do not necessarily represent the views of the HKSARG. WORKING PAPER NO. 35 INITIAL TRANSPORT ASSESSMENT OF DEVELOPMENT OPTIONS Purpose 1. The purpose of this paper is to provide information on the reference transport demand forecasts, assessment of Reference Scenario and framework for option evaluations. Background 2. Under Stage 3 of the HK2030 Study, Development Scenario and Development Options are formulated. The Development Options are then subject to transport, economic, financial as well as environmental assessments. Under the integrated approach adopted for the Study, the transport requirements identified for the Development Options are also assessed in terms of the environmental, economic and financial implications in order that a meaningful comparison of the Development Options could be made. 3. Under the Reference Scenario, various development choices have been considered to satisfy the land requirements. They can broadly be categorised into two different options of development patterns, namely Decentralisation and Consolidation. The details are presented in the paper on Development Options under the Reference Scenario. Assessments have been carried out to identify the transport requirements of the two Development Options in 2010, 2020 and 2030. The findings are summarised in the following sections. Development Options 4. Under the Reference Scenario, the population in 2030 could be in the region of 9.2 million which is only marginally more than the population of 8.9 million for 2016 adopted in the previous strategic planning. -

Hong Kong Guide Hong Kong Guide Hong Kong Guide

HONG KONG GUIDE HONG KONG GUIDE HONG KONG GUIDE Hong Kong is one of the most important finan- Essential Information Money 4 cial and business centers in the world. At the same time, administratively it belongs to the Communication 5 People's Republic of China. It is a busy me- tropolis, a maze of skyscrapers, narrow streets, Holidays 6 department stores and neon signs and a pop- ulation of more than 7 million, making it one Transportation 7 of the most densely populated areas in the world. On the other hand, more than 40% of Food 11 its area is protected as country parks and na- ture reserves where rough coasts, untouched Events During The Year 12 beaches and deep woods still exist. Things to do 13 Hong Kong is a bridge between east and west – it’s a city where cars drive on the left, where DOs and DO NOTs 14 British colonial cuisine is embedded in the very fabric of the city, and every sign is in English, Activities 19 too. But at the same time, the street life is distinctively Chinese, with its herbal tea shops, . snake soup restaurants, and stalls with dried Chinese medicines. You will encounter rem- nants of the “old Hong Kong” with its shabby Emergency Contacts diners and run-down residential districts situ- ated right next to glitzy clubs and huge depart- General emergency number: 999 ment stores. Police hotline: +852 2527 7177 Hong Kong is a fascinating place that will take Weather hotline (Hong Kong Observatory): hold of your heart at your first visit. -

Destinations : Tin King Estate - Admiralty/Central

Residents’ Service Route No. : NR723 Destinations : Tin King Estate - Admiralty/Central Routeing (Tin King Estate - Admiralty) : via Tin King Road, Tsing Tin Road, Tuen Mun Road, Tsing Long Highway, Cheung Tsing Highway, Cheung Tsing Tunnel, Tsing Kwai Highway, West Kowloon Highway, Western Harbour Crossing, Sai Ying Pun Interchange, Connaught Road West, Connaught Road Central, Man Kat Street, Man Cheung Street, Man Yiu Street, Harbour View Street, Connaught Road Central, Harcourt Road, Cotton Tree Drive slip road, Queensway, Rodney Street and Drake Street. Stopping Places : Pick Up : Tin King Road outside Tin Chui Set Down : 1. Connaught Road West House Waterfront Police Station 2. Man Cheung Street Hong Kong Station 3. Drake Street Admiralty Garden Departure time : Mondays to Saturdays (except Public Holidays) 1. 7.00 a.m. 5. 7.55 a.m. 2. 7.15 a.m. 6. 8.05 a.m. 3. 7.30 a.m. 7. 8.15 a.m. 4. 7.45 a.m. 8. 8.30 a.m. Routeing (Central - Tin King Estate) : via Connaught Road Central, Connaught Road West, Wing Lok Street, Hillier Street, Connaught Road Central, Connaught Road West, Sai Ying Pun Interchange, Western Harbour Crossing, West Kowloon Highway, Tsing Kwai Highway, Cheung Tsing Tunnel, Cheung Tsing Highway, Tsing Long Highway, Tuen Mun Road, Tuen Hi Road, Tuen Mun Road, Tsing Tin Road, Ming Kum Road and Tin King Road. Stopping Places : Pick Up : 1. No. 137 Connaught Road Central Set Down : 1. Tuen Hi Road outside Tuen Mun Town Hall 2. Tin King Road outside Tin Chui House Departure time : Mondays to Fridays (except Public Holidays) 1. -

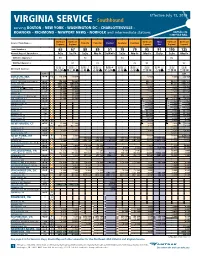

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

Service Delivery to Informal Settlements in South Asia's

SERVICE DELIVERY TO INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS IN SOUTH ASIA’S MEGA CITIES The Role of State and Non‐State Actors By Faisal Haq Shaheen H.B.Sc. (University of Toronto, 1995), M.B.A. (York University, 1997), M.A. (Ryerson University, 2009) a Dissertation presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the program of Policy Studies Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Faisal Haq Shaheen 2017 i Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii Service Delivery to Informal Settlements in South Asia's Mega Cities, the Role of State and Non‐State Actors, Ph.D., 2017, Faisal Haq Shaheen, Policy Studies, Ryerson University Abstract This interdisciplinary research project compares service delivery outcomes to informal settlements in South Asia’s largest urban centres: Dhaka, Karachi and Mumbai. These mega cities have been overwhelmed by increasing demands on limited service delivery capacity as growing clusters of informal settlements, home to significant numbers of informal sector workers, struggle to obtain basic services. -

Road P1 (Tai Ho – Sunny Bay Section), Lantau Project Profile

The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Civil Engineering and Development Department Road P1 (Tai Ho – Sunny Bay Section), Lantau (prepared in accordance with the Environmental Impact Assessment Ordinance (Cap. 499)) Project Profile December 2020 Road P1 (Tai Ho – Sunny Bay Section) Project Profile CONTENTS 1. BASIC INFORMATION ......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Project Title ................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Purpose and Nature of the Project .............................................................................. 1 1.3 Name of Project Proponent ........................................................................................ 2 1.4 Location and Scale of Project and History of Site ..................................................... 2 1.5 Number and Types of Designated Projects to be Covered by the Project Profile ...... 3 1.6 Name and Telephone Number of Contact Person ...................................................... 3 2. OUTLINE OF PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTATION PROGRAMME ........ 5 2.1 Project Planning and Implementation ........................................................................ 5 2.2 Project Timetable ....................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Interactions with Other Projects ................................................................................. 5 3. POSSIBLE -

TAC Annual Report

QUARTERLY REPORT No. 1 of 2018 by the TRANSPORT COMPLAINTS UNIT of the TRANSPORT ADVISORY COMMITTEE for the period 1 January 2018 – 31 March 2018 Transport Complaints Unit 20/F East Wing Central Government Offices 2 Tim Mei Avenue Tamar Hong Kong. Hotline : 2889 9999 Faxline No. : 2577 1858 Website : www.info.gov.hk/tcu E-mail : [email protected] CONTENTS Chapter Page 1 Major Areas of Complaints and Suggestions 4-9 2 Major Events and Noteworthy Cases 10-12 3 Feature Article 13-19 LIST OF ANNEXES Annex A Complaints and Suggestions Received by TCU 20-21 B Trends of Complaints and Suggestions Received by TCU 22-23 C Summary of Results of Investigations into Complaints and 24-25 Suggestions D Public Suggestions Taken on Board by Relevant 26-27 Government Departments/Public Transport Operators E Complaints and Suggestions on Public Transport Services 28-29 F Complaints and Suggestions on the Services of Kowloon 30-32 Motor Bus, Citybus (Franchise 1) and New World First Bus in the Past Eight Quarters G Complaints and Suggestions on Taxi Services in the Past 33 Eight Quarters H Breakdown of Complaints and Suggestions on Taxi 34 Services I Complaints and Suggestions on Traffic and Road 35 Conditions J Complaints and Suggestions on Major Improper Driving 36 Behaviours of Public Transport Drivers 2013 – 2017 K Breakdown of Complaints and Suggestions about Improper 37-38 Driving Behaviour of Public Transport Drivers L Breakdown of Complaints and Suggestions about Improper 39-42 Driving Behaviour of Franchised Bus, Green Minibus, Red Minibus and Taxi Drivers - 2 - M Breakdown of Enforcement Actions Taken against 43 Drivers/Vehicles of Taxi, Public Light Bus and Bus N How to Make Suggestions and Complaints to the Transport 44 Complaints Unit - 3 - Chapter 1 Major Areas of Complaints and Suggestions This is the first quarterly report for 2018 covering the period from 1 January to 31 March 2018. -

Transport Infrastructure and Traffic Review

Transport Infrastructure and Traffic Review Planning Department October 2016 Hong Kong 2030+ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PREFACE ........................................................... 1 5 POSSIBLE TRAFFIC AND TRANSPORT 2 CHALLENGES ................................................... 2 ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE STRATEGIC Changing Demographic Profile .............................................2 GROWTH AREAS ............................................. 27 Unbalanced Spatial Distribution of Population and Synopsis of Strategic Growth Areas ................................. 27 Employment ........................................................................3 Strategic Traffic and Transport Directions ........................ 30 Increasing Growth in Private Vehicles .................................6 Possible Traffic and Transport Arrangements ................. 32 Increasing Cross-boundary Travel with Pearl River Delta Region .......................................................................7 3 FUTURE TRANSPORT NETWORK ................... 9 Railways as Backbone ...........................................................9 Future Highway Network at a Glance ................................11 Connecting with Neighbouring Areas in the Region ........12 Transport System Performance ..........................................15 4 STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT DIRECTIONS FROM TRAFFIC AND TRANSPORT PERSPECTIVE ................................................. 19 Transport and Land Use Optimisation ...............................19 Railways Continue to be -

Aichi Prefecture

Coordinates: 35°10′48.68″N 136°54′48.63″E Aichi Prefecture 愛 知 県 Aichi Prefecture ( Aichi-ken) is a prefecture of Aichi Prefecture Japan located in the Chūbu region.[1] The region of Aichi is 愛知県 also known as the Tōkai region. The capital is Nagoya. It is the focus of the Chūkyō metropolitan area.[2] Prefecture Japanese transcription(s) • Japanese 愛知県 Contents • Rōmaji Aichi-ken History Etymology Geography Cities Towns and villages Flag Symbol Mergers Economy International relations Sister Autonomous Administrative division Demographics Population by age (2001) Transport Rail People movers and tramways Road Airports Ports Education Universities Senior high schools Coordinates: 35°10′48.68″N Sports 136°54′48.63″E Baseball Soccer Country Japan Basketball Region Chūbu (Tōkai) Volleyball Island Honshu Rugby Futsal Capital Nagoya Football Government Tourism • Governor Hideaki Ōmura (since Festival and events February 2011) Notes Area References • Total 5,153.81 km2 External links (1,989.90 sq mi) Area rank 28th Population (May 1, 2016) History • Total 7,498,485 • Rank 4th • Density 1,454.94/km2 Originally, the region was divided into the two provinces of (3,768.3/sq mi) Owari and Mikawa.[3] After the Meiji Restoration, Owari and ISO 3166 JP-23 Mikawa were united into a single entity. In 187 1, after the code abolition of the han system, Owari, with the exception of Districts 7 the Chita Peninsula, was established as Nagoya Prefecture, Municipalities 54 while Mikawa combined with the Chita Peninsula and Flower Kakitsubata formed Nukata Prefecture. Nagoya Prefecture was renamed (Iris laevigata) to Aichi Prefecture in April 187 2, and was united with Tree Hananoki Nukata Prefecture on November 27 of the same year. -

Property Review (Part 2)

30 MTR CORPORATION LIMITED EXECUTIVE MANAGEMENT’S REPORT Property Review 31 She feels glad to have use of the extensive Club House facilities at Tierra Verde. After a hard week at work, there’s nothing better than a game of tennis before relaxing with a juice. was achieved through managers’ remuneration income from newly In Singapore, we won our first property development consultancy completed Airport Railway properties and from other property contract. The Company was selected by the Land Transport management services such as Octopus Access business and MTR Authority of Singapore to provide consultancy services for the Property Agency Company Limited, a wholly-owned subsidiary of packaging and marketing of a 24,980 square metre site situated the Company that provides agency services for the sale, purchase above a proposed Singapore Mass Rail Transit station at Serangoon and leasing of properties in Hong Kong. Central, a residential area located north of the city centre. During the year, our property management-related business Outlook continued to expand and diversify. At Olympic Station, the Central 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 We maintain a cautious outlook for the property market in 2003. Park development of 1,312 residential flats was completed and units Investment properties Distribution of property management income Any sustained improvements in demand for Grade A office space handed over to individual owners, in the process coming under MTR With shopping centres maintained at 100% occupancy levels, strong growth in More properties came under MTR management in 2002 with more to follow will await an upturn in the global economy. -

Paratransit Regulatory Revolution

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository Enoch and Potter: Paratransit regulatory revolution Paratransit: the need for a regulatory revolution in the light of institutional inertia1 Marcus Enoch* and Stephen Potter** *School of Civil and Building Engineering, Loughborough University, Leicestershire LE11 3TU. **Department of Engineering and Innovation, Faculty of Maths, Computing and Technology, The Open University, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA 1 This chapter has been accepted for publication in a forthcoming book about paratransit to be published by Emerald (edited by Corinne Mulley and John Nelson). 1 Enoch and Potter: Paratransit regulatory revolution Abstract Purpose: This chapter adopts a transport systems approach to explore why the adoption of paratransit modes is low and sporadic. Regulatory and institutional barriers are identified as a major reason for this. The chapter then reviews key trends and issues relating to the uptake of, and barriers to, paratransit modes. Based on this analysis a new regulatory structure is proposed. Approach: Case studies and research/practice literature. Findings: Following an exploration of the nature of paratransit system design and traditional definitions of ‘paratransit’, it is concluded that institutional barriers are crucial. However, current societal trends and service developments, and in particular initiatives from the technology service industry, are developing significant new paratransit models. The chapter concludes with a proposed redefinition of paratransit to facilitate a regulatory change to help overcome its institutional challenges. Research Implications: A paratransit transformation of public transport services would produce travel behaviours different from models and perspectives built around corridor/timetabled public transport services.